BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 25, Article number: 683 (2025) Cite this article

Gestational weight gain (GWG) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), as two major adverse pregnancy outcomes, could be affected by diet patterns, and GWG also influenced GDM. Therefore, we aimed to explore the four diet quality scores and two adverse pregnancy outcomes in a more macroscopic way.

667 women for GWG part and 333 women for GDM part who were pregnant from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), aged 20 to 44 years, were involved in this study, respectively. Four diet quality scores including dietary inflammatory index (DII), dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015), and Alternative Healthy Eating Index–2010 (AHEI-2010) were chosen in this study.

We found that higher HEI-2015 and AHEI-2010 were associated with lower risk of GWG, especially for advanced maternal age. Lower DII and higher DASH were associated with lower risk of GDM. These associations were robust after excluding the diabetic patients. For pregnant women with GWG, DASH was negatively associated with the risk of GDM. Summarily, adherence of healthy dietary pattern associated with decreased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Adherence of healthy dietary pattern associated with decreased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. We recommend that pregnant women take dietary precautions with foods consisting of fruits and vegetables, low-fat dairy products, whole grains, and legumes.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most common and serious complication of pregnancy, affecting about 14.0% of pregnant women globally [1]. It is worth noting that the incidence of GDM is increasing and will increase with the prevalence of obesity [2, 3]. GDM could increase the risk of maternal -infant adverse outcomes, and threaten the health of pregnant women and their offspring [4, 5]. Gestational weight gain (GWG), an indicator of maternal fat accumulation as well as uterine, placental, and fetal growth, with the meaning of the nutritional status of a pregnant woman during pregnancy [6]. Moreover, a higher GWG could also increase the risk of GDM [7, 8].

Inflammation has long been hypothesized to play a role in the etiology of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including GDM, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and preterm birth [9]. The underlying mechanism might be that maternal inflammatory molecules could modify the methylation patterns of genes, thereby affecting the birth outcomes [10]. Diet plays a crucial role in managing gestational diabetes. In general, women with GDM should eat a diet rich in vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats [11]. Diet-related inflammation during pregnancy could be causing the increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes [10]. Diet can modulate inflammation, and anti-inflammatory diets can reduce the risk of GDM by reducing chronic inflammation to avoid insulin resistance and modulating the gut microbiota [12, 13]. Therefore, adherence to individual healthy eating patterns might be benefit to pregnancy outcomes.

The Dietary Inflammation Index (DII) is a composite index representing diet-related inflammation, and previous studies have found that anti-inflammatory diets assessed using this index are associated with a reduced risk of GWG and GDM, and that it serves as a predictor of prediabetes in women with prior gestational diabetes [14,15,16]. Dietary Approaches to Hypertension (DASH) is considered to be an effective dietary intervention for lowering blood pressure, and it has also been found to significantly reduce the risk of GDM [17, 18]. The Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015) is a comprehensive measure of diet quality. Studies have found that an increased HEI is beneficial for improving glycemic control in women with GDM and that diet quality as measured by the HEI is associated with excess GWG [19, 20]. The Alternative Healthy Eating Index-2010 (AHEI-2010), which focuses more on foods and nutrients associated with chronic disease risk, has found that adherence to the AHEI-2010 dietary pattern during pregnancy reduces the risk of GDM [21, 22]. Each of these dietary indices has the potential to reduce GDM and GWG.

In summary, we propose the hypothesis that all four dietary indices are associated with GDM and GWG and aim to explore which diet is more suitable for the prevention of GDM and GWG, with a view to informing the establishment of dietary guidelines for pregnant women of appropriate age.

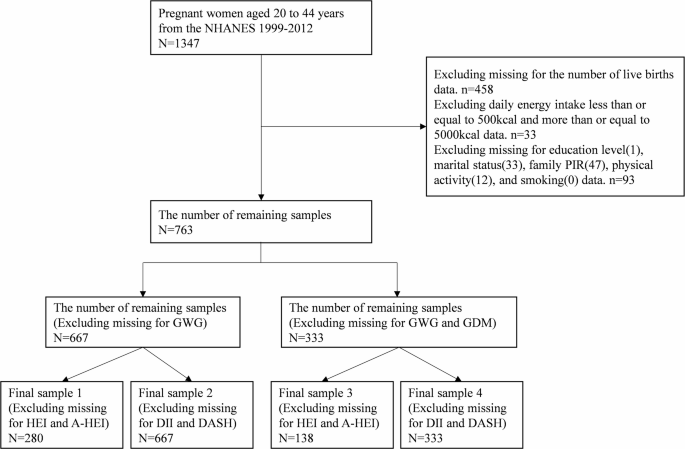

Data were pooled from the 1999–2012 annual survey of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [23] because these cycles investigated the history of live births in pregnant women. 1347 pregnant women aged 20 to 44 years were enrolled, leaving a sample of 763 after excluding missing live birth history, abnormal energy intake, and missing covariates. Two outcome variables (GWG and GDM) and four dietary related indices (HEI, A-HEI, DII, and DASH) missing were subsequently excluded, resulting in four final samples. Details showed in Fig. 1.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

GWG and GDM were the two outcome variables in this study from NHANES 1999–2012. Blood was measured from participants who had fasted for at least 8 h or more, but less than 24 h, and sample vials were stored in appropriately refrigerated (-20 °C) conditions until shipped to the University of Missouri-Columbia for testing. According to the American Diabetes Association’s One-Step Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) strategy, a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) threshold of 5.1 mmol/L was sufficient for a diagnosis of GDM [24]. Each woman’s GWG was categorized as “adequate”, “excessive”, or “insufficient”, based on the difference between each woman’s weight measured at the time of the examination and her self-reported pre-pregnancy weight [25]. Specifically, for all pregnant women in the first trimester, a weight gain of 0.5–2 kg is considered “adequate”. During the second and third trimesters, the recommended weight gain varies by pre-pregnancy BMI: 0.51(0.44–0.58) kg/week for underweight women (BMI < 18.5 kg/m²), 0.42(0.35–0.50) kg/week for normal-weight women (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m²), 0.28(0.23–0.33) kg/week for overweight women (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m²), and 0.22(0.17–0.27) kg/week for women with obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m²).

Dietary related indices and pattern

NHANES conducted two 24-hour dietary recalls using the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Automated Multiple-Pass Method (AMPM) to accurately record dietary intake during the past 24 h at the time of the pregnant women’s participation in the study. The first dietary recall was collected during the MEC interview, and the second was collected during a telephone follow-up 3–10 days after the MEC interview. Participants estimated food portion sizes using a food modeling manual and measurement aids. Reported foods were converted to nutrient data using the USDA Food Coding Database (FNDDS). Four dietary indices such as HEI-2015 [26], A-HEI-2010 [27], DII [28], and DASH [29] were used in this study to assess the effects of diet. Due to data discrepancies between NHANES cycles, HEI-2015 and A-HEI-2010 were calculated using data from the 2005–2012 cycle, and DII and DASH were calculated using data from the 1999–2012 cycle. Details were shown in Supplements.

Covariate assessment

Pregnancy duration was categorized by self-reported month of pregnancy into trimester 1 (1, 2, 3 months), trimester 2 (4, 5, 6 months), and trimester 3 (≥ 7 months) [30]. The family poverty income ratio (Family PIR) was divided into three groups: ≤1.3; 1.3 ~ 3.5; >3.5 [31]. Smoking was divided into three groups: no-smoker, current smoker, and former smoker, based on the questions “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life” and “Do you now smoke cigarettes” [32]. Physical activity data was assessed using the Physical Activity Questionnaire, which was designed based on the World Health Organization’s Global Physical Activity Questionnaire. Physical activity was divided into three groups by metabolic equivalent (MET): inactive (0 MET·min/week), moderate (< 600 MET·min/week), and vigorous (≥ 600 MET·min/week) [33, 34]. The number of live births was divided into three groups: 0 (no live birth history), 1 (one live birth), and ≥ 2 (two or more live births) [35]. Advanced maternal age was divided into two groups: “Advanced maternal age” group (Age ≥35 years old) and “Not advanced maternal age” group (Age < 35 years old) [36].

Four sample groups were analyzed independently. All statistical descriptions and statistical analyses in this study are based on the NHANES complex weighting, thus ensuring a nationally representative sample. Unweighted frequency (N) and weighted percentage (%) were used to describe the categorical variables, and the Rao-Scott chi-square test was used for between group comparisons. Continuous data were expressed using weighted mean ± weighted standard error, and the t-test or ANOVA was used for comparisons between groups. Binary logistic regression and multinomial logistic regression were used to explore the associations of dietary related indices with GDM and GWG, with the no-GDM and GWG “accessive” groups as reference, respectively. Model 1 was not adjusted for covariates. Model 2 adjusted for age, race, education levels, marital status, and family PIR. Model 3 additionally adjusted for smoking, physical activity, number of live births, and total energy intake over Model 2, Model 3 additionally adjusted GWG for GDM, In addition, considering the effect of a history of previous diabetes, we performed another analysis on pregnant women without a history of previous diabetes to test the sensitivity of the results. Subsequently, considering the effects of advanced maternal age and GWG, we performed interaction analyses. IBM SPSS 24.0 was used in this study. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among 280 participants who investigated GWG and HEI/A-HEI, the mean age was 29.73 ± 0.58 years old, 19.4% were insufficient weight gain, 7.8% were adequate weight gain, and 72.8% were excessive weight gain, as shown in Table 1. Among 333 participants who investigated GDM and DII/DASH, the mean age was 28.24 ± 0.40 years old, 15.6% with GDM and 84.4% without GDM. The results of the tests of participant characteristics and between-group differences by GDM and GWG subgroups were shown in Supplement 5.

The results of the logistic regression showed that higher HEI was significantly associated with a decreased risk of insufficient GWG (P = 0.002), OR was 0.888(0.825,0.956), after adjusting for all covariates. Higher A-HEI was significantly associated with a decreased risk of insufficient GWG and excessive GWG (P = 0.002, P < 0.001), ORs were 0.840(0.754,0.935) and 0.797(0.729,0.871), respectively. No statistically significant associations between DII or DASH and the prevalence of insufficient or excessive GWG were observed, as shown in Table 2. However, increased DII was a risk factor for the development of GDM (P = 0.012), OR was 1.931(1.163,3.205), and higher DASH was significantly associated with a decreased risk of GDM (P = 0.028), OR was 0.677(0.479,0.957), as shown in Table 3. After deleting participants with a history of diabetes, none of the above results have changed, as shown in Supplement 6.

Then considering the high risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women of advanced maternal age, we performed a multiplicative interaction analysis, as shown in Table 4. The interaction coefficient (β-interaction) of advanced maternal age on insufficient GWG and excessive GWG per 1 count HEI increase were − 0.460(-0.713, -0.207) (P-interaction = 0.001) and − 0.446(-0.673, -0.217) (P-interaction < 0.001), respectively. The β-interaction of advanced maternal age on insufficient GWG and excessive GWG per 1 count A-HEI increase were − 0.307(-0.555, -0.057) (P-interaction = 0.017) and − 0.288(-0.514, -0.062) (P-interaction = 0.014), respectively. These suggested negative interaction on the multiplicative scale. However, for GDM, we did not find an interaction between dietary index and advanced maternal age, as shown in Supplement 7.

Subsequently, considering the effects of GWG for GDM, we performed a multiplicative interaction analysis, as shown in Table 5. The β-interaction of insufficient GWG and excessive GWG on GDM per 1 count DASH increase were − 2.263(-3.912, -0.625) (P-interaction = 0.008) and − 2.137(-3.772, -0.498) (P-interaction = 0.012), respectively.

Diet was strongly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes; thus, we have explored the four diet quality scores and the two adverse pregnancy outcomes by a nationally representative population. The mainly founding are as follow: Firstly, higher HEI-2015 and AHEI-2010 were associated with lower risk of GWG, especially in advanced maternal age; adherence of DASH and anti-inflammatory diet were associated with decreased risk of GDM. Secondly, for pregnant women with GWG, adherence of DASH was benefit to preventing GDM. Thirdly, the associations between diet quality scores and adverse pregnancy outcomes were robust after excluding diabetic patients.

The prevalence of adverse pregnancy outcomes among women with GDM has increased in the United States from 2014 to 2020, and effective interventions for GDM are an effective way to avoid adverse pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women [37]. Risk factors for GDM include overweight and obesity, advanced maternal age, previous history of GDM, family history of type 2 diabetes, race, diet, and physical activity. Among those that can be effectively intervened are diet and avoidance of obesity due to excessive GWG during pregnancy [38,39,40]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed the effectiveness of dietary interventions in gestational diabetes [41]. A low GI diet has been found to slow the increase in blood glucose concentration, thereby reducing the burden on pancreatic β-cells and increasing insulin efficiency [42]. In addition, diets aimed at reducing GWG have been found to be effective in reducing the incidence of GDM [43]. At the same time, diets can be effective in reducing excess GWG. The Pregnancy Environment and Lifestyle Study (PETALS) suggested that diet quality measured by the HEI-2010 is associated with excessive GWG [19], which was consistent with our study. Additionally, a prospective cohort study observed that women with poor or fair diet quality gained, on average, 2 kg more than those with higher-quality diets [44].

In addition, advanced maternal age presents additional challenges, as it is associated with elevated risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirth [45]. Our study revealed a particularly pronounced association between HEI/AHEI dietary patterns and GWG among older pregnant women. These findings highlight the importance of dietary interventions for this high-risk population. Specifically, we recommend strict adherence to the HEI-2015 and AHEI-2010 dietary guidelines as an effective strategy to mitigate GWG risks, with particular emphasis on women of advanced maternal age.

Although there was no association between DII and GWG in this study, other study has been found higher inflammatory level associated with higher GWG rate in the pregnant women [46]. In addition, diets with higher HEI/AHEI scores, characterized by abundant fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, improve insulin sensitivity by reducing postprandial glucose spikes and systemic inflammation. These diets are rich in fiber and antioxidants, which enhance pancreatic β-cell function and mitigate oxidative stress [47, 48]. Thus, pregnant women are not advised to ignore the diet-related inflammation. All pregnant women should be encouraged to consume a healthier diet throughout their pregnancy to prevent adverse maternal and fetal outcomes due to the development of GWG [49].

Anti-inflammatory diet and DASH were recommended to adhere to prevent GDM during pregnancy based on our study. A Finnish study revealed that a high inflammatory potential of the diet was associated with an increased risk of GDM [16], which was consistent with our founding. Dietary fats were regarded as one reason factor between inflammation and GDM, they could increase the presence of chronic, systemic inflammation due to total fat, SFAs, and trans fatty acids have a high inflammatory potential [28, 50]. DASH eating plan, which was rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products, is a low-GI low-energy-dense diet, used to lower blood pressure, initially [51, 52]. However, it has also been reported playing an important role in diabetes and the metabolic syndrome [53, 54]. A meta-analysis concluded that diets resembling DASH diet in early pregnancy were associated with lower risks or odds of GDM [17]. Moreover, other high-quality diets were also recommended for pregnant women to adhere. It was reported that a high AHEI 2010 score was associated with a reduced risk of GDM by 19% or 46% [22, 55].

Avoiding excessive GWG also might be a potential strategy of prevention of GDM for pregnant women [40]. A previous study from the Japanese Birth Cohort pointed that the effect of diet on the occurrence of GDM depends on pre-pregnancy BMI [56]. Our study suggested that for pregnant women with GWG, it was more important to adherence of DASH eating plan to prevent of GDM. This result may be useful in providing individualized preconception counselling based on maternal circumstances.

The four dietary indices in this study have a number of shared components that may be beneficial in preventing GWG and GDM, including high dietary fiber, low glycemic load and anti-inflammatory components [57, 58]. These dietary components prevent GDM and GWG by regulating glucose homeostasis, reducing pro-inflammatory factors, and alleviating oxidative stress, among other mechanisms [59, 60]. Therefore, we recommend that pregnant women should prioritize incorporating these beneficial dietary components into their daily nutrition. Future development of dietary indices for pregnancy should emphasize these evidence-based components. Dietary guidelines for pregnant women should specifically highlight the importance of these protective nutritional elements.

This study has some strengths. First, this study is based on the NAHENS complex weighted design, which provides a good representation of the population. Second, this study used four widely used dietary indices to assess diets, and the results have good reliability. There are also some limitations in this study. First, this was a continuous cross-sectional study, which may have had some self-report bias, and it was also not possible to determine the chronological order in which exposures and outcomes occurred, and therefore causal associations could not be determined. Second, the sample size may have been small and therefore subgroup analyses may have been difficult. Thirdly, as different dietary indices are calculated using different NHANES cycle data, there may be potential effects. Finally, the dietary indices used in this study were developed for the whole population, and there is still a need to develop dietary indices that are specifically designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of the diets of pregnant women.

Adherence of healthy dietary pattern associated with decreased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Higher HEI-2015 and AHEI-2010 were associated with lower risk of GWG. Adherence to DASH and an anti-inflammatory diet was associated with a lower risk of GDM. We recommend that pregnant women take dietary precautions with foods consisting of fruits and vegetables, low-fat dairy products, whole grains, and legumes that are characterized by high dietary fiber, low glycemic load, and anti-inflammatory components.

The data underlying this article are available in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) at https://www.n.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/default.aspx.

- GWG:

-

Gestational weight gain

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- NHANES:

-

National health and nutrition examination survey

- DII:

-

Dietary inflammatory index

- DASH:

-

Dietary approaches to stop hypertension

- HEI-2015:

-

Healthy eating index-2015

- AHEI-2010:

-

Alternative healthy eating index–2010

- Family PIR:

-

Family poverty income ratio

Not applicable.

This work was partly supported by the Doctor of Excellence Program, The First Hospital of Jilin University (No:JDYY-DEP-2024025).

The NCHS Research Ethics Review Board approved the protocols of NHANES of the National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. ID: NCHS IRB/ERB Protocol # 2011-17、Continuation of Protocol #2011-17. All subjects were provided with written informed consent.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Li, Y., Zheng, H., Jiang, W. et al. Which dietary pattern should be adopt by age-appropriate pregnant women to avoid gestational weight gain and gestational diabetes mellitus. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 25, 683 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-025-07801-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-025-07801-y