What's Not to Like about "Unlikeable Characters"?

When I think of the characters I love from literature, they’re all unlikeable. I have always preferred the buffoons, fuckups, jerkwads, oddballs, lunatics, egomaniacs, halfwits, and sad sacks to your morally upstanding and psychologically healthy citizens. Characters like Charles Kinbote, Merricat Blackwood, Ignatius J. Reilly, Emerence, Sula, Ahab, and the many unnamed and unhinged yet unforgettable narrators. The Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, Gallants and Goody-Two-Shoes of literature have rarely compelled me. Such characters tend to be bland and repetitive. Their actions predictable. Their thoughts routine. Isn’t the whole point of literature to see things from different points of view? To experience the consciousness of characters who are unusual or at least unlike us?

Obviously, some readers disagree with me. One of the most common complaints you hear about books today is that the protagonists or main characters are “unlikable” or “hard to relate to.” (Villains, of course, are supposed to be hated.) Authors are asked in interviews if they’d “like to be friends” with their narrators and online writing advice is cluttered with tips to avoid the “trap” of unlikable characters and write likable ones. Even when books are praised, reviewers often feel the need to warn readers that the protagonist might be unlikable.

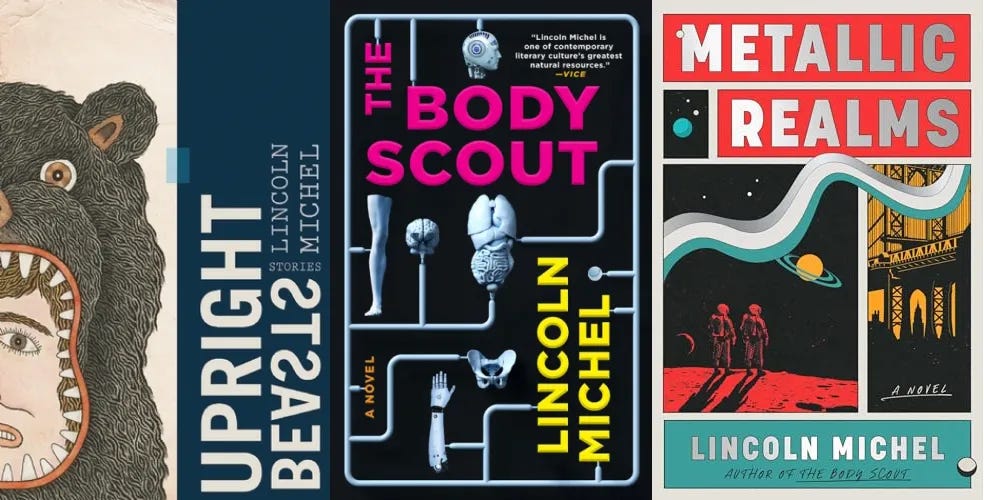

I’ve experienced this myself with my new novel Metallic Realms. (Obligatory “it’s in stores now! Check it out!” parenthetical aside here.) I’ve received very lovely reviews—which is to say the following is not a complaint—but I couldn’t help but notice that even the raves tended to mention the narrator is a lot to handle. I don’t think the reviewers are wrong to say so. Reviews exist, in part, to inform readers of whether they’ll enjoy a book. Clearly, some readers are put off by the very qualities that make me pick up a novel.

To each their own. People will read whatever they like. But, I think some readers are missing out on many of the pleasures—perhaps even the point—of literature. Art has no rules, but I will argue that art should encompass everything. We should have the entire gamut of characters, and the full range of human psychology, in fiction. A literature of only Ted Lassos would be a dire place. So, here I offer a little ode to the misanthropes, freaks, and unhinged characters that, in my book, make literature interesting.

First, we must define what we mean by likable. Part of what I’ve always found strange about “unlikable character” discourse is that it seems to conflate very different meanings of “like.” I’d argue there is not just a gap but an enormous chasm between “likable” as in 1) “I’d like to be close friends with this protagonist and have them as a member of my biweekly trivia club!” or 2) “I like all of this character’s moral and political opinions because they mirror mine” and 3) “likable” as in “I’d like to follow this person’s thoughts in a fictional narrative.”

Only the third interests me in literature. Let’s call 3) “compelling” characters to distinguish from the former uses of “likable.” Compelling characters can be likable in the sense of psychologically healthy and morally upstanding people you’d want to be friends with. It’s possible. Though, for me, such characters need to be at least a little weird or unusual. To have that je ne sais quoi that makes me go hmm, okay, oui. The reason compelling characters are rarely likable is that—as I’ve argued before—all likable characters are alike; each unlikable character is unlikable in their own way.

If readers want characters to always do the “right” things, avoid thinking the “wrong” thoughts, and to be forever pleasant and never off-putting, then there is a very narrow band they can exist within. The characters blur together. Writers who fret about this tend to write from a defensive posture that causes them to smooth away the rough bumps and odd edges that make characters unique.

Writers often compensate by focusing on identifying categories and backstories yet too often leave those identities surface level and the backstories in the background. They don’t alter the characters’ actual character (or interiority) in the present story. Here, the fretting about “likable characters” gets entwined with another problem in too much modern fiction: a lack of interiority. Any type of character, even those whose only struggle is to be good and do right, can be compelling if we get their interiority and their psychology.

The preference for “likable characters” is often given moral and political import. You must have good characters and correct anything bad they do in the text so the reader knows what is good and bad. While I’m skeptical fiction is the place to instill morality, writers ironically undermine this mission. They make their heroes indistinct yet get to have freedom and fun while creating their villains. The villains then become the compelling characters. If you are worried your readers will identify with the “wrong” traits, this seems like a backward way to do it.

Anyway, those who insist on linking politics to likability might look at where real-world preferences for “likable” politicians who you’d “want to get a beer with” has gotten us…

Why is “unlikable character” discourse so prevalent in literature specifically? It is basically expected that our acclaimed television shows, for example, will feature characters that are awful in many ways. White Lotus, Mad Men, The Wire, Girls, Succession, Breaking Bad, The Sopranos, etc. Some of those are composed entirely of unlikable characters. Ted Lasso-type shows are notable for being the exception. Perhaps this is a consequence of the mediums. The screen provides us with human actors who give an inherent likability—at least if the actor is good—to even the most depraved character. The page cannot. But I’m not sure that’s enough of an explanation. American literature was long defined by its anti-heroes, misfits, and downright sociopaths. Jay and Daisy, Marlowe and Spade, Humbert Humbert, Bigger Thomas, Bunny, Bateman, so on and so forth.

Why is there so much focus on likable characters in literature when film, television, video games, and other artforms are more popular and certainly more influential for children? I fear that it might be exactly literature’s shrinking cultural impact that has led us here. Panicked publishers and worried writers trying to please the remaining readers by offering them the safest work at a lukewarm temperature no one can quite object to even if few can really love.

Maybe not. Maybe it is in fact the power of literature, its ability to immerse you fully in another consciousness in a way film and TV cannot, that makes some readers react badly to “bad” characters. If so, I think it useful to fight that impulse. To embrace compelling characters with all their warts and scars intact. To see inside a unique and weird mind is to be reminded all our minds are weird and unique. There is great pleasure in letting yourself experience the individual obsessions, specific delusions, weird rationalizations, horrible hopes, and bizarre worries of people who are different than you.

If I am forced to make a moral argument about literature, it is that this is what is good for us. Reading not to see a mirror reflecting our thoughts and experiences back at us, but reading to see in new ways.

I don’t think that we should read characters who think differently than us for some vague quality of “empathy.” (Here I must recommend Namweli Serpell’s excellent essay “The Banality of Empathy.”) I don’t know if reading stories from the points of view of others helps other people. But I think it helps us. Good art enlarges us. Good literature allows us to think in new and different ways, and that in turn expands our ability to see and understand the world.

Yes, we live in an age where literature’s status is shrinking and people’s attention is fractured between social media, film, TV, video games, and a million other things. But the response should not be to shrink literature itself. To make it as small and safe as possible. Literature’s advantage on other artforms is the ability to enter other consciousnesses. Books take us into the thoughts and minds of others in a way visual artforms cannot. We need literature that lets us into the minds of as many compelling characters as possible, even if—perhaps especially if—they are oddballs, losers, weirdos, haters, and the unlikable. Don’t they need understanding most of all?

In personal writing news, the Chicago Tribune recommended Metallic Realms this week, saying it “builds an elegant homage to imagination.” Other reviews have called Metallic Realms “Brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), and “Just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.