In 1972, American audiences witnessed one of the most infamous pieces of horror cinema ever made. , by then-newbie filmmaker Wes Craven, broke all the rules and showed an alternate side of society in the aftermath of the decade of peace and love. It was a heavily criticized film, but some critics were able to see the essence beyond the senseless violence and depravity of its villains. Roger Ebert, the famed critic who didn't always celebrate horror, was one of them. More than 50 years after the release of Craven's directorial debut, the critic's words are more relevant than ever:

"I don't want to give the impression, however, that this is simply a good horror movie. It's horrifying, all right, but in ways that have nothing to do with the supernatural."

You got that right, Roger. That last house on the left wasn't haunted, and it didn't have to host ghosts in order to be a horrific place. It was just a place where evil met evil, and fire was fought with fire. The Last House on the Left isn't just a cathartic experience in the revenge genre. It's a film that delivers its message of revenge without making the "good" people the victims of a merciless act. They are just the purest expression of a dark desire that everyone harbors inside when thinking about justice.

Related

10 of Roger Ebert’s Favorite Thriller Movies

From 'Rear Window' (1954) to 'Ripley’s Game' (2002), these are some of renowned film critic Roger Ebert’s favorite thriller movies.

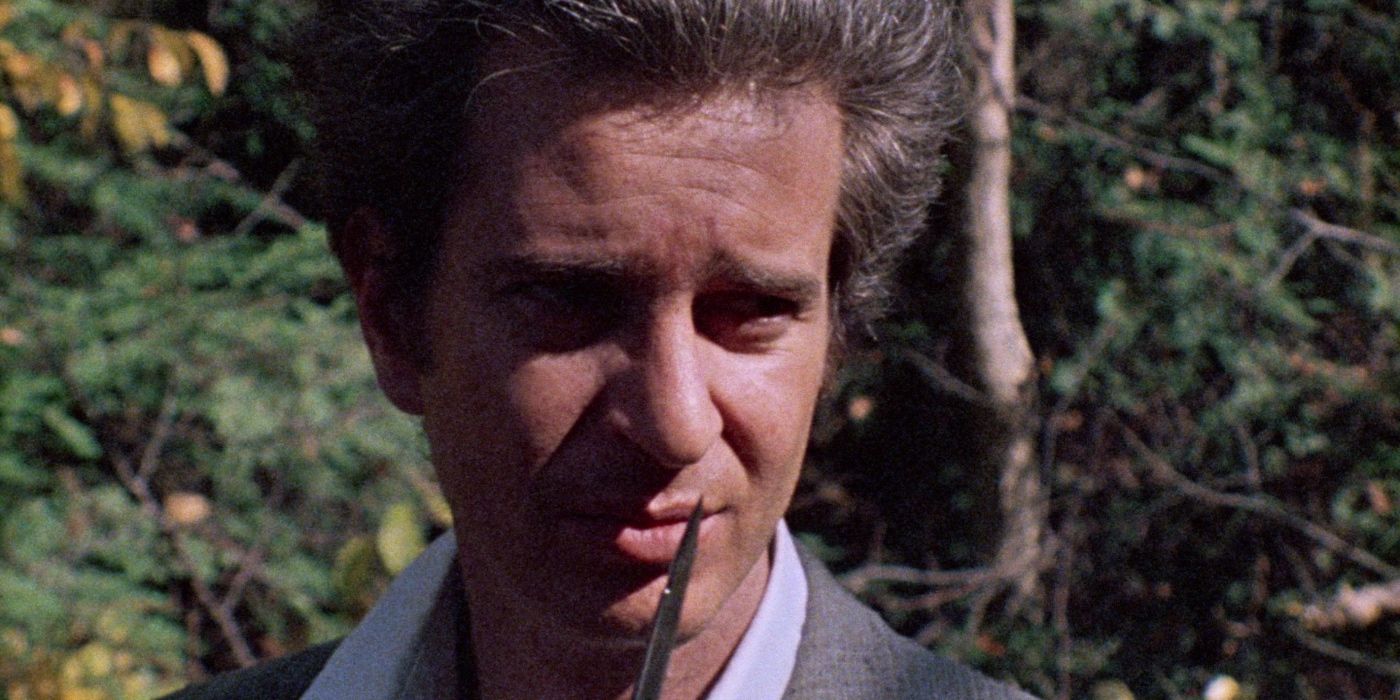

Supposedly based on a true story, The Last House on the Left follows teenagers Mari Collingwood and Phyllis Stone as they embark on a journey through hell itself. While they're on the way to a concert, the teens are kidnapped, tortured and eventually murdered by a gang of maniacs who have reunited after two killers escaped from prison.

Unbeknownst to them, the killers arrive at the doorstep of the Collingwood family. The family welcomes them into their own home, and they ultimately realize they are in the home of one of their victims. When Mari's parents find out they have killed the teenagers, they decide to go on a rampage to viciously murder their new guests and indulge in coldblooded revenge.

Wes Craven and Sean Cunningham, who would eventually become the directors behind genre icons A Nightmare on Elm Street and Friday the 13th, became good friends in 1970, and two years later, their names would be printed on an infamous movie poster. The poster of The Last House on the Left showed Phyllis' battered body as she leaned on a tree. It was a piece of promotional art that hinted at the idea that the movie was too shocking, and audience members had to repeat to themselves that it was "just a movie." This "advice" was an understatement, considering what the film ended up causing upon release.

At the time, the giallo subgenre was still a fairly new concept, and Hollywood was still a few years away from high-concept horror movies like The Exorcist. There were no films like The Last House on the Left, which openly blurred the line between horror and the unexplored and extreme side of "hardcore" films. In fact, Craven's initial idea was to make a pornographic film, but upon starting production, he decided to make a change. The film's opening scene bears some similarity to a "hardcore" storyline, but Craven ultimately incorporated the storyline of the Swedish ballad "Töres döttrar i Wänge," which Ingmar Bergman had already adapted in his film The Virgin Spring. Craven's adaptation was just more graphic, more violent, and more shameless.

The production of the film was not easy, especially when it came to scenes involving sexual violence. Nevertheless, Craven was able to come up with a final cut, which was then butchered by censors and theater owners who refused to show the cut approved by the MPA (formerly known as the MPAA). In some countries, like New Zealand and the United Kingdom, the film was banned and was only released on home video in the early 2000s. In the United States, The Last House on the Left had a limited release, which resulted in a great box office performance, as the film cost less than $100,000 and made more than $2 million.

More than half a century later, the first question that comes to mind when discussing The Last House on the Left is whether the movie is really that controversial. The answer, regardless of which cut you can watch today, is that yes, the movie still feels as nihilistic, unrestrained and bleak as ever. Everything that made it controversial back then is still poignant and effective today. It is not an easy movie to watch, and not even the most experienced horror hound will avoid feeling a bit squeamish.

Roger Ebert, the critic who once slaughtered films in the Friday the 13th franchise and even called one of them "an immoral and reprehensible piece of trash," was not usually a fan of horror movies. There were exceptions, of course, and Craven's revenge movie stood among these. Per Ebert's review of the film:

"The Last House on the Left is a tough, bitter little sleeper of a movie that's about four times as good as you'd expect. There is a moment of such sheer and unexpected terror that it beats anything in the heart-in-the-mouth line since Alan Arkin jumped out of the darkness at Audrey Hepburn in Wait Until Dark.

"What does come through in "The Last House on the Left" is a powerful narrative, told so directly and strongly that the audience (mostly in the mood for just another good old exploitation film) was rocked back on its psychic heels."

Ebert also highlighted the movie's sharp disconnection from a formula-based narrative. The Last House on the Left may have pioneered the exploration of "revenge is a dish better served cold" vendettas as the basis of better revenge movies, where the concept of "eye for an eye" is more satisfying when carefully planned. The critic continues:

"Wes Craven's direction never lets us out from under almost unbearable dramatic tension… The acting is unmannered and natural, I guess. There's no posturing. There's a good ear for dialogue and nuance. And there is evil in this movie. Not bloody escapism, or a thrill a minute, but a fully developed sense of the vicious nature of the killers. There is no glory in this violence. And Craven has written in a young member of the gang (again borrowed on Bergman's story) who sees the horror as fully as the victims do. This movie covers the same philosophical territory as Sam Peckinpah’s "Straw Dogs" (1971), and is more hard-nosed about it: Sure, a man's home is his castle, but who wants to be left with nothing but a castle and a lifetime memory of horror?"