Archives of Public Health volume 83, Article number: 151 (2025) Cite this article

Measuring health-related unmet needs is crucial for identifying innovation gaps and developing targeted strategies to address them. This study focused on measuring the unmet needs of patients with Crohn’s disease in Belgium using a standardised methodology that can facilitate comparisons across different diseases. Crohn’s disease is a chronic condition characterised by a rising incidence over the past century and limited progress in understanding its causes or advancing effective treatments.

We conducted an online survey (n = 150) and semi-structured interviews (n = 20) with adults affected by Crohn’s disease. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse survey results, and thematic analysis was applied to interview transcripts. Unmet needs were classified a-priori into health, healthcare, and social aspects.

The study revealed unmet needs beyond the well-known symptoms of Crohn’s. One in five survey respondents waited over a year for a diagnosis, and 18% considered their treatment as rather or very burdensome. At least 75% reported diarrhoea, fatigue, and abdominal cramps as rather or very burdensome, and around 40% experienced rather or very burdensome stress, anxiety, or depression. These symptoms, perceived as invisible, caused embarrassment, impacted sexual and family life, and led to social withdrawal. Psychological support was generally deemed insufficient, and around 40% of survey participants would have liked to be more involved in treatment decision-making. Only 50% of respondents who had interrupted work for at least a month returned to previous work levels, and 65% of the whole sample experienced financial impacts due to the disease.

Crohn’s patients experienced not only burdensome physical symptoms, but were also frequently affected by significant psychological symptoms, which significantly affected their quality of life. Although specialist care was adequate, faster diagnosis and better psychological support are needed. Future studies should explore the unmet needs of children and adolescents with Crohn’s disease to complete the picture.

Text box 1. Contributions to the literature |

|---|

• Within a largely supply-driven innovation ecosystem, measuring health-related unmet needs is crucial for transitioning towards a more needs-driven approach. |

• Using a standardised method to measure unmet needs enables valuable comparisons across health conditions, which is vital for guiding effective healthcare prioritisation. |

• There is limited evidence on the unmet needs of Crohn’s disease patients in Belgium. |

• Patients with Crohn’s disease were found to face unmet needs that extend beyond physical symptoms. |

• Describing the full spectrum of health-related unmet needs associated with Crohn’s disease is essential to design interventions that are meaningful from the patient perspective. |

Over the last century, the incidence of Crohn’s disease (CD) in Europe has increased significantly to levels in 2020 ranging from 0.4 to 22.8 cases per 100 000 person-years [1]. No specific prevalence measures exist for Crohn’s Disease in Belgium, but it was estimated that in 2021 around 151 per 100 000 individuals in Belgium lived with an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease or Ulcerative Colitis [2]. CD is a life-long, chronic immune-mediated disease, characterised by acute flare-ups and periods of remission [3, 4]. Most patients develop their first symptoms between the ages of 15 and 25 years and often experience symptoms for years before receiving a correct diagnosis due to the heterogeneous and non-specific nature of initial symptoms [5].

Although its exact pathophysiology is not yet fully understood, it is widely accepted that CD is the result of an inappropriate gut mucosal immune response, triggered by dysbiosis in genetically susceptible individuals [6, 7]. It is believed to be caused by an interplay of genetic factors, the immune system, the intestinal microbiota, and other risk factors [8]. There exists no curative or disease-halting treatment, therefore the current management aims to relieve symptoms, prevent complications, and improve the quality of life. The therapeutic options include drug therapy (such as anti-inflammatory drugs, immunomodulators, and biologics), surgery, and lifestyle changes such as physical activity, dietary changes and smoking cessation [9]. After 10 years of being affected by the disease, 30% to 40% of patients are reported to have developed complications such as fistulae, abscesses, perianal disease, ulcers or strictures which may require surgical resection [10,11,12]. Although, the mortality rate of CD is considered low, it is associated with complications and comorbidities, including malnutrition, post-operative complications, and a higher risk of colorectal cancer, which can, in turn, affect life expectancy [13].

It is well established that CD can profoundly impact patients'lives [14], yet few studies have systematically assessed the broad range of potential unmet needs of patients with CD, with research often focusing on the broader category of IBD [15,16,17]. To the best of our knowledge, no study to date has employed a standardised needs-assessment method that eventually allows for comparability across diseases. Furthermore, a recent narrative review highlighted key unmet needs in the clinical evaluation and treatment of CD, emphasising the necessity for further research into other types of unmet needs [14].

Understanding which dimensions of patients’ lives are most affected and the resulting consequences is essential for identifying innovation gaps and, based on this, developing targeted strategies—whether pharmaceutical, social, or otherwise. More broadly, accurately measuring the full range of current unmet needs is crucial for transitioning towards a more needs-driven innovation approach. Using a standardised method to measure unmet needs allows for meaningful comparisons across different health conditions, which is vital for guiding effective healthcare prioritisation. The NEED study allows for such a comparison in its open-access database (https://healthinformation.sciensano.be/shiny/NEED/).

The present study aimed to investigate the unmet health-related needs of individuals living with Crohn’s disease in Belgium by using a framework developed in the context of the Needs Examination, Evaluation and Dissemination (NEED) project [18].

This study is based on the NEED framework (Supplementary Table 1), which distinguishes between health-related needs from a patient perspective and those from a societal perspective, each encompassing healthcare, health, and social needs [18].

From the patient perspective, healthcare needs concern the needs for healthcare services in a broad sense, including medical treatments, contact with healthcare professionals, but also preventive measures, nursing care, etc.

Patient health needs are defined as needs for better health (e.g. in case of illness, disability, or injury) and highlight the burden of the disease, including how much pain, suffering, reduction in wellbeing and quality of life the health condition is causing to patients despite current treatment [18].

Social needs pertain to aspects of the socio-economic environment of patients, such as social life and work.

An unmet need is considered to arise when the available offer or supply of health-related interventions does not, or not completely, meet the existing needs [19]. The results presented in this article focus specifically on the needs from the patient perspective (as opposed to the societal perspective) and are conveyed in a narrative format, structured according to the NEED framework criteria for each type of need (healthcare, health, and social). These criteria represent a set of needs that were identified based on systematic reviews and expert consultations [18]. The NEED project consistently assesses these needs for different health conditions (in this case, Crohn’s disease). In the results section, we report on all measured criteria, and in the discussion we highlight the results which we believe to be salient and which can be considered as significant unmet needs.

The manuscript was written in accordance with the STROBE checklist [20].

A mixed-methods approach was used, which included an online patient survey and in-depth individual interviews with patients.

Development of the online questionnaire

The questionnaire used in the survey (Supplementary File 2) was an adaptation of a generic questionnaire previously developed within the NEED project to identify and assess patients’ needs across various health conditions [21]. This generic questionnaire was reviewed by a Delphi panel including representatives from umbrella patient organisations and sickness funds in Belgium. The response options concerning symptoms, treatment options, treatment side-effects, types of healthcare professionals, and services used were adapted to the context of CD. Face validity of the questionnaire (in Dutch) was assessed by two gastro-enterologists specialised in IBD. Afterwards, the questionnaire was translated into French.

Recruitment of participants

Survey participants were recruited through the Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE) website and social media platforms, and posters and flyers in healthcare settings. Information about the survey was also shared with sickness funds, disease-specific and umbrella patient organisations, hospitals, and universities, all of which relayed the information. The survey was available online from May 4 to July 2, 2023.

Participants had to report being at least 18 years old, having received a diagnosis of Crohn’s Disease from a healthcare professional at least two months prior, and residing in Belgium. We allowed other adults to complete the survey on behalf of individuals affected by Crohn’s disease who met the inclusion criteria if those individuals were unable to participate themselves. If a participant completed the survey on behalf of another adult, they were required to answer as if the patient were responding.

Analysis of survey results

For continuous variables (age, EQ-5D-5L utility scores), we calculated the mean together with the standard deviations (SD) or 95% confidence intervals (CI), while for categorical variables, we used percentages. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) utility scores were assigned to respondents’ EQ-5D-5L health state descriptions using the most recent Belgian value set [22]. Participants self-reported two EQ-5D-5L scores: one based on their recollections of health status just before disease onset, and another reflecting their perceptions at the time of survey completion. A paired-sample t-test was conducted to determine whether there was a significant difference between the mean utility scores before onset of the disease versus at the time of survey completion. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyse categorical variables. The significance level was set at 0.05 for all statistical tests. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.0.

Development of the interview guide

The interview guide was based on the generic tool developed in Maertens de Noordhout et al. [21] [21], and adapted to CD. The questions were also slightly adapted for each respondent, based on their answers to the survey. The interview guide was finalised in French and then translated into Dutch. The final interview guide covers: patient journeys leading to the diagnosis, symptomatic impact of the disease on patient’s lives, treatment experience, encountered obstacles, information and support networks, relationships with the medical profession, and social relations.

Selection of participants

Interview participants were chosen from survey respondents who expressed their willingness to participate. To ensure a diverse representation, the selection among volunteers was based on specific characteristics. We aimed to conduct 20 individual interviews, evenly split between French and Dutch speakers, ensuring a diverse representation of respondents. Participants were selected based on segmentation criteria such as age, time since diagnosis, and treatment type, with two volunteers chosen per segment per language. When segments lacked sufficient volunteers, candidates from adjacent categories or other language groups were contacted to fill the gaps. The segmentation tree is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Data collection process

Semi-structured interviews were conducted online via Teams© (non-physical face to face) in July and August 2023 by French or Dutch native-speaking researchers trained in qualitative interviews and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews lasted approximately one hour each. To ensure confidentiality, all names of participants, institutions, and care providers were anonymized.

Analysis of interviews

Qualitative deductive thematic analysis was performed using NVIVO® software. This was guided by the criteria of the NEED framework, while allowing for the identification of new themes beyond those originally specified. Native speakers coded the interviews, and two researchers collaborated to develop a shared nodes tree.

The study received approval from the ethics committee of the ‘Erasmus Hospital Brussels’ (P2023/148/B4062023000088).

Survey participants

Of the 258 individuals who initiated the survey, five were ineligible. Furthermore, questionnaires missing mandatory responses were excluded (n = 103). Consequently, the final dataset included 150 respondents with a self-reported diagnosis of CD (see Supplementary Fig. 2), out of which 5% were proxies responding on behalf of a person affected by Crohn’s who were unable to respond themselves.

The sample consisted of 72% women, the mean age was 43.4 years (SD: 13.7), and 57% of participants had a university degree (Table 1). The majority of participants (62%) were diagnosed more than ten years ago and around one quarter had undergone surgery due to CD.

Interview participants

As planned, 20 interviews were conducted. Among those interviewed, 60% were female, 75% had been diagnosed 10 or more years ago, and 40% had undergone surgery due to CD (see Supplementary Table 2).

Diagnostic timing

Nearly half of survey respondents decided to seek medical attention within three months following the onset of symptoms. Once they decided to consult, 50% were able to find medical attention within a month. Almost 60% received the diagnosis within two months of their first consultation, but 19% waited over a year for a diagnosis.

During the interviews, patients explained that the non-specific nature of their symptoms initially led to differential diagnoses focusing on common gastrointestinal issues like irritable bowel syndrome or viral gastroenteritis. Sometimes combined with general practitioners'lack of familiarity with Crohn’s disease, these delays resulted in frustration and feelings that their condition was not adequately investigated. Some participants only received the correct diagnosis once they were referred to a university hospital. Certain patient characteristics (e.g., being a healthcare professional, having a doctor in the family, participating in clinical trials) were reported to speed up the diagnostic process by facilitating quicker access to medical appointments.

"We fiddled a little bit with the diagnosis, I have to admit that… I even went as far as [Name of University Hospital] in an ambulance to see a specialist at the time, to confirm the disease. I remember being hospitalised for a long time, I think I stayed in the hospital for a month and a half, on an empty stomach, with a central line – which had to be changed twice by the way […].”

Interview participants also reflected on the compartmentalisation of medical specialisations, noting that doctors sometimes focused narrowly on their own domain, delaying the recognition of broader systemic issues. The high number and the invasiveness of diagnostic procedures (ultrasound, biopsy, blood tests, stool analysis, gastroscopy, colonoscopy, and entero-MRI) were perceived by patients as lengthy and burdensome.

Accessibility of care

Thirteen percent of participants mentioned that they did not receive care when they needed it (Table 2). The most common reported reasons for foregone care were the long waiting times to get an appointment (5%), the lack of competent staff (5%), and the lack of information (4%). During the interviews, patients also highlighted geographic barriers to receiving the needed care.

“Especially if you want to go to specialised care, in my case you have to bridge a certain distance, [region-region]. Indeed, that is not next-door.”

Effectiveness of treatment

One of the most salient unmet healthcare needs expressed during the interviews was the need for improved treatment or management of gastrointestinal symptoms, which profoundly impacted patients’ HRQoL, their psychological well-being, and social life. While surgical treatments were often deemed effective, patients noted the difficulty of finding a lasting pharmaceutical solution, as effectiveness was frequently temporary, requiring new trials over time. They also found drastic diets unsustainable long-term due to their restrictive nature and social challenges, with no clear dietary guidelines available, leading to a reliance on personal trial and error.

“Since I've had surgery and I've been on treatment, we've finally found the right treatment because I've been on five different treatments. I'm on the fifth I think now, I have absolutely no other options left.”

“No, it really didn't work, so we changed. Then I took another molecule […]. It didn't work either. I think that after a year I was already unresponsive and here I am […] it's been a month and a half that I'm really not well […] so I'm at the stage where I'm wondering if it's still worth taking a treatment.”

Experienced burden of treatment and its side-effects

Although 86% of survey participants expressed being overall “very satisfied” or “satisfied” with their treatment, 17.9% (n = 26) found it very or rather burdensome (Table 2). Of these 26 participants, 85% (n = 22) reported that the burden was primarily attributed to treatment side-effects.

During the interviews, participants explained that treatments imposed constraints on their lives, activities, and access to care, because they were time-consuming or complex, required significant self-discipline, regular hospital visits and routine investigations (e.g., blood tests), or had practical considerations such as necessitating refrigerator storing. Maintaining long-term treatment discipline was particularly difficult without close clinician follow-up.

“There are the effects of the operations. They play a psychological role because we're not prepared to go back and forth to the hospital. We were promised that the [stoma] bag would be the miracle solution, and it's true that I had regained quality of life in terms of trips to the toilet and the pain, but I got other things in return.”

The side-effects of treatment that were most frequently reported as very or rather burdensome in the survey (Table 2) were fatigue or exhaustion (64.1%), weight gain (28.3%), skin irritation or eczema (23.5%), and diarrhoea (19.3%). However, interviewees noted that it was often unclear whether diarrhoea and fatigue were symptoms of the disease or side effects of the treatment. They mentioned that the constraints of medication sometimes led them to question whether continuing treatment was worth it. Some interview participants expressed a desire to stop taking the drugs, whether because of severe side effects or as a personal goal, not wanting lifelong dependence on medication. Side effects from surgery, such as changes in abdominal appearance, were also noted as challenging to cope with daily.

“Yes, I also have that as an additional side-effect of taking that medication. So it is not Crohn's-related, but medication-related that I have skin cancer. […] According to the dermatologist, the major cause is [name immunomodulator A].“

“I was nauseous all the time, nothing was going through […], I had loss of appetite. I would make myself food, and I would be like,"oh, that looks great". Then when I had the dish in front of me, it was impossible to eat.”

Quality of care

Over 75% of survey participants were satisfied with their healthcare providers. The main areas of dissatisfaction with healthcare mentioned in the interviews were the limited availability of specialists and nurses causing rushed consultations, the fact that rotation between senior and junior staff affected continuity of care, as well as the perceived lack of competence in some physicians. The latter was evidenced, according to interviewed patients, by post-operative complications, inappropriate medication dosages, or a general lack of professionalism. Interviewees also criticised the lack of a holistic approach, the dehumanisation of care making them feel “like a number”, and its over-specialisation leading to fragmented care. Navigating through different medical specialisations was challenging for some, despite recognising the benefits of a multidisciplinary approach. They emphasised the useful inclusion of other team members in the care continuum such as nurses and social workers. Better guidance and structured care pathways were suggested, similar to pathways for diabetes or renal failure. In addition, there was an expressed need for psychological support alongside pharmacological treatment and medical procedures.

“It goes well as long as you can keep seeing the same doctor, who knows your trajectory, who already has experience that you react or don't react to things in a particular way and who doesn't want to reinvent the wheel every time. But in the University [hospital] it's the assistants. And every time different assistants, assistants who don't know my record. […]“

“So you see, we feel that the medical system is under pressure. We feel that visits with the surgeon are 5 min, quick quick, we talk but there is no examination, there is really nothing ultimately.”

Information

Around 15% of survey participants reported that they received insufficient or no information from healthcare professionals, and only 9% reported that the provided information was not very clear or not clear at all (Table 2). During the interviews, the reasons for dissatisfaction with information included a lack of proactivity from healthcare professionals, insufficient guidance on which specialists to consult, and the fact that information was shared too quickly and was sometimes difficult to understand. The importance of how doctors communicated the diagnosis was also highlighted, with key factors being compassion, frankness, and time devoted to explaining the disease and its consequences.

“I'm telling you, sometimes I'm the one who has to ask for a vaccination:"Do you think I should get vaccinated, Doctor?"So"yes, obviously you have to get vaccinated, because you have low immunity.""Oh well, thank you for telling me!";"Do I have to go see the dermatologist Doctor?","Oh yes yes, of course you…". But frankly no, it's not through my doctor that I found the info, no, it's me.”

Furthermore, 43% of survey participants (excluding those who answered “not applicable”) expressed a desire to be more involved in decisions regarding their treatment (Table 2). Some interviewed patients reported having been informed and having the final say in treatment choices, while others felt they were expected to follow directives. Patients generally trusted their doctors'expertise but sometimes felt that their concerns were overlooked and hesitated to challenge the doctor’s recommendations, although they feared contradicting the doctor's authority.

“At one point he told me 'you absolutely have to take corticosteroids again', I said 'no, I don't want to'. So basically, we made a deal (laughs), … It's laughable but that's the way it is.”

“The contrast is evident again between [hospitals]. For example, [in this one hospital] when they say okay, we're going to start with this, and it's like okay, that’s it. Whereas in [region], they literally had brochures, you name it, those and those options, that you can choose from: that, that, that or that. So you did indeed have much more say, much more control. As it were, patients had the last word in [region].”

Impact on general health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

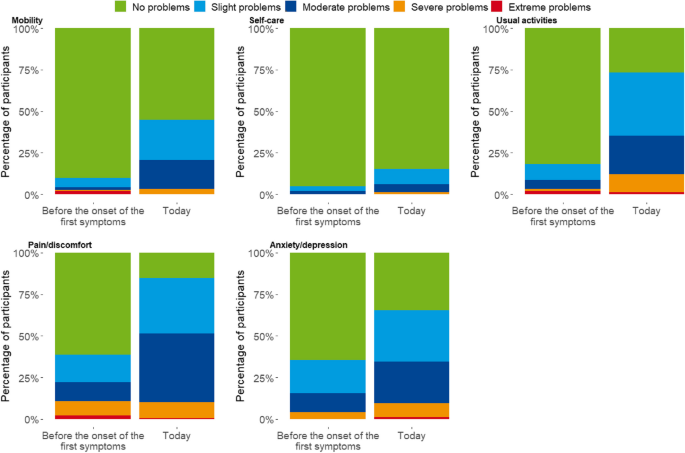

The EQ-5D-5L utility score assessed through the survey showed a significant decrease from 0.85 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.82; 0.88) before disease onset to 0.70 (95% CI: 0.67; 0.74) at the time of the survey (mean difference −0.15; 95% CI: −0.20; −0.10; p < 0.0001), indicating a reduction in HRQoL related to the disease.

Crohn’s disease led to an increase in the proportion of slight, moderate and severe health problems in all EQ-5D-5L dimensions (Fig. 1). The most important increases were in difficulties performing usual activities (+ 55.3% points), pain/discomfort (+ 46.0% points), mobility (+ 34.7% points), and anxiety/depression (+ 30.0% points), compared to a smaller rise in the self-care dimension (+ 10.6% points).

Self-reported level of problems on each EQ-5D-5L dimension before the onset of first symptoms of CD and today, NEED Crohn’s disease survey, Belgium, 2023 (n=150)

The highest increase in number of individuals reporting severe problems concerned the ability to carry out usual activities (+ 9.4% points) and anxiety/depression (+ 4% points). Few participants reported extreme problems across any EQ-5D-5L dimension.

Interviewees highlighted their emotional and sexual life as another dimension negatively impacted by the disease, which occasionally lead to the deliberate choice not to have children.

“For example, sexually as well. So if you sleep somewhere else now, because you have no control over your anus, in my case, and you go to sleep somewhere, or with someone, or in a hotel or whatever. So, in your head, knowing that you are not at home, if you encounter that at home, it's not a problem, you clean it up and… you try to cover up. That's not easy. Sexually, it's the same thing. It's not… so logical for someone who suddenly loses their bowel movements, that's not… You can't just flip a switch, and that's not easy. And if you do enter into new relationships, how do you explain it?”

Impact on physical health

The physical symptoms that were reported as very or rather burdensome by the highest number of survey participants were diarrhoea (78.0%), fatigue or exhaustion (76.0%), and abdominal cramps (70.0%) (Table 2). Interviewed patients described the burdensome consequences of the physical symptoms, including a permanent state of weakness which required rest and impacted daily activities (e.g. driving).

“Been home for a week, and I found the fatigue very heavy, I would always sleep and sleep”

Impact on psychological health

The psychological symptoms that were reported as very or rather burdensome by the highest number of participants were stress (42.7%), fear or anxiety (37.3%), and feeling down, depressed or sad (37.3%) (Table 2). In the interviews, patients mentioned that the invisibility of the disease affected them psychologically.

“Physically, it's not visible when we're not feeling well, so it's not like having a broken arm or a cast on your foot, people don't see it and so it's like 'stop complaining'. We're in pain, we turn white because of the pain, but people don't realize it. So no, the people around us don't understand.”

One cause of stress was the fear of the condition progressing over time. While treatment ineffectiveness caused hopelessness, the physical symptoms, like uncontrolled bowel movements, caused embarrassing and socially awkward situations which also had a significant psychological impact.

“I went for a walk, I had just eaten, and now, fortunately, it was in the woods [...] I had a little accident and psychologically, well, I wasn't ready. And it's silly because we tell ourselves it can happen to anyone in fact but, yes it still has a psychological impact.”

Impact on social life

A bit more than half of respondents (54.0%) reported needing social support in at least one area without receiving it (Table 2). The most frequently reported unmet social support needs included talking to other patients about the disease (23.6%), administrative or social support (20.1%), more help with day-to-day activities (16.9%), and talking about things other than health problems (16.2%).

Interviewed patients talked about having to change their social and leisure activities, such as sports and travelling, to take into account the implications of their disease (lacking energy, medicine transportation issues, severity of symptoms). They often hesitated or refused social activities to avoid embarrassing situations due to insufficient access to toilets. This, they explained, led to isolation and withdrawal from family life and social interactions. Changes in physical appearance due to the illness itself or due to its treatment also increased the desire to avoid social activities.

“Sometimes we're afraid to go to people's houses, for example to sleep in people's homes, I don't dare to sleep too much. Because sometimes the consequences are a little embarrassing. But after a while of saying ‘I don't do all this’, you end up getting used to it and you live well with it.”

“I've already said that to my partner, I would really like to do yoga, but I sometimes don't dare because I think: suppose I have gas in the intestine or air in the intestines and that flies out unwillingly, because that happens sometimes, then it's not so nice.”

Support from loved ones was considered crucial by interviewed participants, especially during medical appointments or severe flare-ups. Importance was given to empathy, help with daily tasks, and ensuring access to toilets.

“Fortunately, I have a good partner who supports me enormously in this and is very understanding in that area. That makes a difference. For example, he will do the cleaning and cooking. He's going to take a lot off your hands. The moments when I have to lie down on the couch or sleep longer or something, for example, he actually takes on a lot.”

Some interviewees considered relationships with other Crohn's Disease patients beneficial for exchanging experiences and finding encouragement. For them, patient support groups provided valuable information and interaction opportunities. However, other participants found these interactions counterproductive due to frequent negativity and misinformation and preferred not to be reminded of their illness.

“I say it, the people at the hospital themselves who give a lot of support, also know that there is an association where you can always ask questions or meet fellows. The fact that you are not alone. I am well surrounded. I have a lot of people who understand me and are going to assist me.”

Another challenge that was raised by interviewees concerned the administrative hurdles associated with the disease. In Belgium, obtaining reimbursement for certain drugs required annual application renewal, causing stress and potential treatment interruptions. The process involved multiple administrative steps and communication channels, leading to delays and frustration. This meant that patients spent significant time on administrative tasks, impacting their professional and personal lives. Pharmacists were identified as precious in assisting with navigating the administrative procedures and ensuring medication availability.

Impact on work

Two thirds (68.8%) of respondents who were employed at the time of their diagnosis had to interrupt their work for at least one month. Among these, 28.1% ended up reducing their work hours and 17.2% did not return to work due their disease (Table 2).

Interviewed patients explained that Crohn's led to work absenteeism due to various reasons, including flare-ups, poor general health, medical appointments, and hospitalisations. Repeated absences and productivity loss caused guilt, and feelings of injustice due to criticism or disciplinary actions. In addition, access to toilets at work, especially in certain jobs, was a significant issue. Despite these constraints, many patients wanted to continue working as if they were not ill.

“That is to say, I will have to consider a 4/5 ths because I accept the fact that I will never be able to work full-time again, that I have to preserve my health. But that means that again for my pension, etc., well… I will have done a part-time job, even though I would like nothing better than to work full-time.”

Financial consequences of disease

Fifty-six percent of participants reported experiencing a financial impact due to medical costs (Table 2). Interviewees also mentioned being financially affected by the accumulation of many small non-healthcare expenses, such as parking fees, household help, toilet access fees, and protective underwear during flare-ups. Some investigations or treatments (e.g. probiotics, vitamins, food supplements) were minimally reimbursed or not reimbursed at all.

“Magnesium, calcium when I was taking cortisone etc., well all that, it's still quite expensive, probiotics etc. Well these are things that you have to take as a supplement in the end… So all this is not reimbursed. But on the other hand, all the medical appointments related to the disease, so all the blood tests, additional analyses, the little that is still at our expense is still reimbursed by the public insurance company. But here's the thing, not everything that's a treatment add-on is reimbursed. And so sometimes it adds up to […] yes, 150€ per month some months.”

Frustration was also expressed concerning private life insurance premiums which increased because of the diagnosis of Crohn’s, or even excluded them from coverage.

The patient survey and the interviews provided an in-depth insight into the perceived unmet health-related needs of people with Crohn’s Disease in Belgium. The disease had a substantial impact on individuals’ health-related quality of life. The most burdensome physical symptoms were diarrhoea, fatigue, and abdominal cramps, while stress, anxiety, and depression were the leading psychological challenges. The invisibility of Crohn’s sometimes led to feelings of illegitimacy, where patients felt misunderstood by family, employers, and colleagues.

Unmet healthcare needs mainly concerned diagnostic delays, the lack of effective treatment, high treatment burden, and the lack of psychological support. The diagnostic process was lengthy and burdensome for many, with nearly one in five participants waiting over a year for a diagnosis. This was attributed to insufficient awareness among GPs, the need for invasive investigations, long waiting times for medical imaging, and the compartmentalisation of medical specialisation(s). One in six patients found their treatment burdensome primarily due to side-effects like fatigue, weight gain, and skin problems. Furthermore, 43% of participants reported that they would have liked to be more involved in the treatment decision-making process.

Study participants highlighted that Crohn’s also had a significant impact on their social life, requiring adaptations in their diet, leisure activities, sexual life, and social habits. These challenges were primarily driven by the severity of symptoms and by the fear of experiencing socially embarrassing situations. Almost half the working individuals with Crohn’s had to reduce work or had stopped working due to their illness. A financial impact of the disease was reported by more than half of the survey participants, attributed to loss of income due to the reduced working ability, as well as medical expenses, and non-healthcare costs. Half of survey respondents also reported not having received social support when they had needed it, which included particularly administrative support.

Some of the unmet health-related needs identified in this study for individuals living with CD in Belgium were also identified in other studies. Three previous studies highlighted the impact of the disease on psychological health, the lack of psychological support and inconsistent screening for depression [15, 23, 24]. A literature review identified fatigue as a highly prevalent and burdensome symptom in patients with IBD, with an important impact on the QoL [25]. Our study identified diarrhea and fatigue as the most burdensome reported symptoms. However, in the Adelphi Real World IBD Disease Specific Programme, which used data from France, Germany, Italy, and Spain, one third of CD patients reported abdominal pain as the most burdensome symptom and their HRQoL was worse than that observed in our study. Regarding unmet healthcare needs, a qualitative patient preference study in Belgium also noted the need for improved treatment of gastro-intestinal symptoms, because of their high impact on HRQoL and well-being, and expressed concerns regarding the safety and long-term effects of treatment [15]. While our study highlighted significant delays in diagnosis, these were shorter than in a previous study where almost one third of respondents waited longer than a year to receive a diagnosis [27]. In the IBD2020 survey, which covers eight European countries, communication with healthcare providers was identified by patients with CD and ulcerative colitis as one the most important drivers of care quality [28]. However, respondents in the IBD2020 survey felt more involved in decisions about their treatment than in our survey. Scheurlen et al. [14] reported that pharmacological and surgical treatment complications and treatment failure emphasized the need for research on standardised clinical approaches, reliable biomarkers, new treatment agents, and addressing diverse clinical manifestations [14].

Regarding the unmet social needs, a European survey (2010–2011) showed that 40% of individuals with IBD had made adjustments in their working lives (e.g. flexible hours, part-time), 25% were absent from work for more than 25 days, and 31% even lost or quit their job due to their disease, which posed financial burdens on patients and their families [27]. In another study, 10.8% of patients with CD had reduced their working hours owing to their disease and 11.2% of those with CD had stopped working altogether [26]. This is lower than reported in our study where around two thirds of the working individuals with Crohn’s interrupted their work for at least 30 days, and out of these, almost half had to reduce work or had stopped working due to their illness. However, this difference may be related to the fact that only patients who worked before the disease entered the denominator.

As this study was conducted in Belgium, it is uncertain whether the results can be extrapolated to patients from other countries. While unmet health needs for Belgian patients may be more easily generalisable to CD patients elsewhere, unmet healthcare and social needs are more strongly influenced by a country’s health and social care systems and cultural factors. A study reported that South Asian cultures and/or religions can lead to additional challenges for adults living with IBD, such as stigma surrounding ill health and the use of complementary and alternative therapies [29].

This study uses a comprehensive patient-centred approach to provide evidence on the unmet health-related needs of individuals with CD. This evidence can help to develop patient-relevant outcome measures and should be incorporated in the decision-making processes of various healthcare stakeholders, including policymakers, researchers and the industry, to foster a more needs-driven healthcare innovation and policy system.

Despite its contributions, there are some methodological considerations that must be taken into account for the interpretability of the study. The recruitment through patient organisations, medical professionals and hospitals might have excluded individuals at the margins of healthcare (e.g. lacking access to healthcare or infrequently followed-up). While these individuals might be few, their unmet needs are likely more significant. The online survey method might have excluded vulnerable populations lacking internet access or technological skills, as reflected by the overall high education level of participants. Administering the survey online was a way of collecting data in a timely manner while allowing to include a large proportion of the patient population. Nevertheless, this choice might have led to an underestimation of the unmet needs of the population of individuals living with CD. In addition, the use of convenience sampling may have introduced selection bias.

It is important to note that the diagnosis of Crohn's disease was self-reported by participants. One of the survey items asked participants how long ago they had received the diagnosis, with one of the response options being,'I have not been diagnosed by a doctor'. Those selecting this option were excluded from the survey. While there is a possibility that some individuals might have falsely claimed to have received a doctor's diagnosis of Crohn's disease, we consider this risk to be minimal due to the lack of incentives for participation and the unlikelihood of patients misunderstanding such a specific diagnosis.

Allowing other adults to complete the survey on behalf of individuals affected by Crohn’s disease was a measure intended to reduce selection bias associated with oversampling of healthier patients. While we cannot be certain of the accuracy of answers provided by proxies (i.e. the extent to which they reflect what the affected individuals would have responded), we believe this approach is a valuable way to give a voice to those who might otherwise remain unheard and to highlight potential unmet needs in populations that could not be surveyed directly.

The fact that many respondents initiated the survey but subsequently closed it (103 out of 253) may indicate that those who eventually participated were different to those who did not. For instance, participants who completed the survey may have had more time available, a higher level of education enabling them to fully engage with the survey, more severe symptoms increasing their motivation to participate, or, on the contrary, less severe symptoms allowing them to concentrate for longer. However, because we have no data on non-participants we cannot draw any conclusions. Concerning the selection of interviewees, it was not possible to achieve a perfect representation of the full spectrum of all combinations of patient characteristics, which may have resulted in the omission of the specific needs of particular profiles. Nevertheless, the included interview sample was heterogeneous and can be considered to provide a relevant representation of patient characteristics. It must also be considered that the unmet needs relating to more distant past events (e.g. diagnostic timing, HRQoL before disease onset) may be prone to inaccuracies in recollection resulting in random error, or to recall bias if there were systematic differences between individuals with older diagnoses and those with more recent diagnoses. Some of these past unmet needs might also be outdated due to changes in healthcare organisation.

The exclusion of participants under the age of 18 was deliberate because the current questionnaire is not adapted for younger individuals. Future studies focusing on the health, healthcare, and social unmet needs of children and adolescents with Crohn’s would be a vital complementary study.

This study shows that important unmet needs persist in the context of Crohn’s disease. Within unmet health needs, this study highlights an important burden of physical but also psychological symptoms, impacting patients’ health-related quality of life in various ways (particularly limiting their ability to perform usual activities). Other aspects such as sexual life, social life, and working ability are also heavily affected, and this burden is often felt to be invisible. Concerning unmet healthcare needs, the study highlighted significant delays in diagnosis, a desire for greater involvement in treatment decision-making, insufficient treatment effectiveness coupled with a significant burden of side-effects, as well as lacking psychological support. Insufficient social support was also uncovered, particularly in terms of navigating the complex administrative hurdles associated with the disease. The findings of this study may assist health policymakers, regulators, HTA bodies, payers, researchers and the pharmaceutical industry in their decision-making processes by considering the unmet health-related needs of patients. This could foster the development of more effective and safer pharmaceutical or nutritional solutions, improve environmental adaptations such as access to toilets, advance knowledge on primary prevention, enhance psychological and social support for patients, and increase disease awareness to facilitate better integration of patients into working and social life.

Data is provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files, as well as in the publicly available NEED database (https://healthinformation.sciensano.be/shiny/NEED/) under the following citation: NEED collaborators (2024). Unmet health-related needs for three selected health conditions in Belgium (v2024-10-10) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12749982 [30].

We would like to thank Jonas Dobbelaere, Tessa van Montfort, Yan Zhi Tan for analysis. Thank you to Peter Buydens, Peter Bossuyt, Sophie Vieujean and Severine Vermeire for their clinical expertise. We would also like to acknowledge the patient associations and healthcare providers for helping distribute the survey, and Sabine Corachan and Nathalie Swartenbroekx for the project management. A special thank you to all participants in the study.

This work was supported by the Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre and the Belgian Science Policy (grant RT/23/NEED).

All study participants provided written informed consent. The study received approval from the ethics committee of the ‘Erasmus Hospital Brussels’ (P2023/148/B4062023000088).

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Schönborn, C., Levy, M., De Jaeger, M. et al. Unmet health-related needs in patients with Crohn’s disease in Belgium: a mixed-methods study. Arch Public Health 83, 151 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-025-01632-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-025-01632-1