BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies volume 25, Article number: 124 (2025) Cite this article

Cancer is currently the second most common cause of death worldwide and is often treated with chemotherapy. Music therapy is a widely used adjunct therapy offered in oncology settings to attenuate negative impacts of treatment on patient’s physical and mental health; however, music therapy research during chemotherapy is relatively scarce. The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of group music therapy sessions with patients and caregivers on their perceived anxiety, stress, and wellbeing levels and the perception of chemotherapy-induced side effects for patients.

This is a retrospective cohort study following the STROBE guidelines. From April to October 2022, 41 group music therapy sessions including 141 patients and 51 caregivers were conducted. Participants filled out pre- and post-intervention Visual Analogue Scales (VAS) assessing their anxiety, stress, and wellbeing levels, and for patients the intensity of chemotherapy-induced side effects.

The results show a statistically significant decrease of anxiety and stress levels (p < .001), an increase in well-being of patients and caregivers (p < .001, p = .009), and a decrease in patients’ perceived intensity of chemotherapy-induced side effects (p = .003). Calculated effect sizes were moderate for anxiety, stress, and well-being levels, and small for chemotherapy-induced side effects.

This is the first study regarding group music therapy sessions for cancer patients and their caregivers during chemotherapy in Colombia. Music therapy has been found to be a valuable strategy to reduce psychological distress in this population and to provide opportunities for fostering self-care and social interaction.

Music therapy should be considered as a valuable complementary therapy during chemotherapy. However, it is crucial to conduct prospective studies with parallel group designs to confirm these preliminary findings.

In 2020 nearly 19.3 million new cancer cases were reported and with a global mortality of around 10 million deaths per year, cancer is currently the second most common cause of death worldwide [1, 2]. According to the Global Cancer Observatory of the WHO, 113,221 new cancer cases and 54,987 cancer deaths were reported in 2020 in Colombia [3]. However, due to the scientific, pharmacological, and therapeutic advances that have improved survival outcomes, cancer has also become a chronic health disease. It is estimated that in the next 20 years the number of cancer patients will increase by nearly 50%, exceeding 28 million cases [1, 4].

Facing a potentially life-threatening disease always results in profound changes in the routine of patients and their families. Moreover, society sees cancer as synonymous with death, pain, and mutilation of the body, which can lead to further difficulties when patients receive the initial diagnosis of their disease [5]. But cancer has not only a profound impact on patients, but also on the physical, emotional, and social wellbeing of caregivers [6]. Previous research shows that those who care for cancer patients can experience high levels of anxiety, depression, and emotional distress, particularly at the start of chemotherapy [6, 7]. Furthermore, emotional burden in caregivers is often exacerbated by factors like the duration and intensity of the chemotherapy [8]. Similarly, caregivers often mask or hide their own feelings for fear of upsetting those they care for, intensifying in this way their own distress [9].

In addition to the psycho-social risks of the illness, cancer treatment is also physically demanding for patients. Chemotherapy, the intravenous administration of antineoplastic drugs in repeated cycles is one of the most frequently used cancer treatments [10]. Chemotherapy aims to eliminate cancer cells through cytotoxicity while they are dividing; usually the faster the cells divide, the more sensitive they are to treatment. In 2018, global chemotherapy use was estimated to be 57.7% [11]. And although chemotherapy contributes to survival, it can also generate various side effects in patients [12,13,14].

Chemotherapy-induced physical side effects are classified from grades 1–4 (mild to life-threatening) and can affect all body organs. Immediate toxicity can be observed for example in hair, skin, blood, or in the gastrointestinal system of patients, while severe side effects may include signs of paralysis, spasms, or ataxia [15]. Additionally, social, emotional, mental, and spiritual health can also be affected during chemotherapy treatment. In a study on women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer, clinically significant depression was found in 37.5% of patients and was associated with chemotherapy duration, anxiety levels, or physical side effects, among others [16]. In a Brazilian study, 37% of cancer patients showed clinically significant levels of depression and anxiety on the first day of chemotherapy, although the prevalence of anxiety was reduced to 4.6% and for depression to 5.1% on the last day of treatment [17]. Lee et al. [18] reported clinically significant anxiety levels and depression in Hispanic populations (52% and 27%, respectively) prior to starting the first chemotherapy session, with time passed since the initial diagnosis being a significant predictor for both mental health difficulties [18].

To ameliorate these challenges, complementary therapies are frequently sought out by patients themselves, but also offered by healthcare institutions. Complementary therapies might include non-western medical approaches such as Ayurveda or Traditional Chinese Medicine, but also acupuncture, yoga, homeopathy, guided imagery, mind–body therapies, or music therapy/music medicine, among others [19,20,21]. Music medicine describes the use of music by other healthcare professionals than music therapists, and most often includes pre-recorded music listening experiences [22]. Music therapy, on the other hand, has been defined by the American Music Therapy Association as “the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program” [23].

Both music therapy and other music medicine interventions have a long tradition in oncology settings. A recent update of a previous Cochrane Review from 2016 [24] included 81 studies with 5,576 participants and found a large effect for reducing anxiety level and improving quality of life and a moderate effect on reducing depression symptoms and pain levels [25]. Similar effects of music interventions on psychological and physiological outcomes with cancer patients are reported by other meta-analyses [26,27,28,29,30]. With respect to end-of-life care in oncology, music-based interventions were also found to increase quality of life, as well as reduce pain, anxiety, and depression [31].

While there is solid evidence for the effectiveness of music-based interventions and therapies for cancer patients in general, studies focusing specifically on music therapy during chemotherapy are relatively scarce. A recent meta-analysis including nine RCTs showed significantly improved anxiety levels and quality of life of patients receiving music interventions during chemotherapy, but not significant effects on depression [32]. Individual studies report that listening to pre-recorded music can improve patients’ quality of life and mental health during intravenous chemotherapy [33] and that playing patient-preferred music can reduce the physical side effects of chemotherapy and improve vital signs [34]. It has also been found that the use of soft music and nature sounds during chemotherapy reduced levels of post-chemotherapy anxiety in patients more effectively than a verbal relaxation exercise [35]. Recorded music has also been used alongside other therapeutic modalities. For instance, recorded monochord sounds and recorded progressive muscle relaxation were found to significantly improve the state anxiety levels of gynecologic cancer patients during chemotherapy [36]. It has also been reported that listening to pre-recorded relaxing music in tandem with periorbital massage reduced nausea and vomiting in gastrointestinal cancer patients [37]. Similarly, Turkish researchers found that listening to serene instrumental music during a guided visual imagery exercise decreased symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and anxiety levels in chemotherapy patients [38].

With respect to music therapy, Ferrer [39] investigated the effects of familiar live music for chemotherapy patients, showing a statistically significant improvement in anxiety levels, fear, relaxation, fatigue, and diastolic blood pressure. Lesiuk [40] found that mindfulness-based music therapy was able to effectively reduce negative mood states and fatigue, as well as increase in energy levels among women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Another study reported that both recreative (e.g., playing instruments and singing) and receptive (e.g., music-listening) music therapy in addition to standard care improved pain perception in chemotherapy patients [41]. More recently, Chirico et al. [42] studied the effects of virtual reality and relaxing music recorded by a music therapist for breast cancer patients during chemotherapy, finding that both virtual reality and music therapy were useful interventions for anxiety reduction and general mood improvement. Romito et al. [43] reported a single integrative music therapy group session for women with breast cancer provided by a certified music therapist and a clinical psychologist. Several music therapy methods and techniques were used together with emotional expression strategies, and resulted in a statistically significant reduction stress, anxiety, depression and anger in the intervention as compared to the control group [43].

These findings from the existing literature demonstrate the potential of music therapy interventions as a means of targeting the emotional and physiological hardships inherent to chemotherapy and serve as a basis for the present study, which seeks to evaluate the impact of group music therapy sessions that involve both patients and caregivers.

To evaluate the impact of group music therapy sessions during chemotherapy with patients and caregivers on their perceived anxiety, stress, and wellbeing levels, and the perception of chemotherapy-induced side effects for patients.

This is a retrospective cohort study, evaluating the outcomes of group music therapy sessions held at the Cancer Institute Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá between April 13th and October 14th, 2022. This study follows the STROBE guidelines for observational studies [44].

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, CCEI-16508–2024, on June 18th, 2024. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the interventions and data collection. The study fully adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki.

The interventions took place at the Cancer Institute of the University Hospital Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá. The Cancer Institute is located in a newly constructed six-story building, which includes medical consulting rooms, and a chemotherapy, day hospital, and hospice floor. The chemotherapy floor consists of 17 cubicles separated by glass walls and each with a curtain that can be left open or closed for privacy. Each cubicle seats two individuals: one patient and one caregiver. The music therapy service forms part of the oncology healthcare team since 2018, and is aligned to the hospitals goals regarding humanization and person-centered care [45].

Participants who attended the group music therapy sessions at the Cancer Institute were adults between the ages of 40 and 60, primarily diagnosed with breast cancer, lung cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, myeloma, lymphoma, and melanoma. The participants were at various stages of their chemotherapy treatment and received infusions at varying intervals depending on medical indication. Caregivers were adults above 18 years old and, in most cases, formed part of the patient’s nuclear family (i.e., spouses, siblings, and children). In some cases, patients were accompanied by professional caretakers, such as nurses.

Inclusion criteria were oncology patients receiving chemotherapy at the Cancer Institute and their respective caregivers who participated in at least one group music therapy session during the study period. No exclusion criteria were imposed.

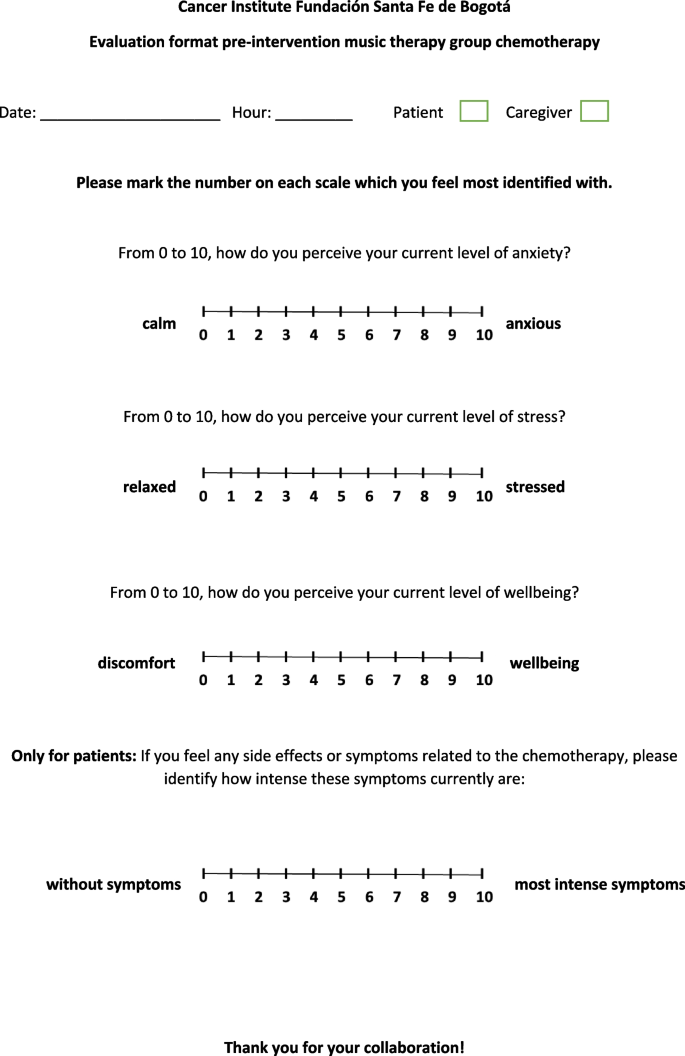

Pre- and post-group music therapy data was collected with visual analog scales (VAS), consisting of a 10-cm line divided into 10 points separated by 1 cm. Each VAS had an introductory phrase indicating what the scale aimed to measure, accompanied by contrasting adjectives written either at the side of 0 or 10, helping participants to understand the direction of the VAS. For anxiety levels, 0 was accompanied by “calm” and 10 by “anxious”. For stress levels, 0 was accompanied by “relaxed” and 10 by “stressed”. For wellbeing levels, 0 was accompanied by “discomfort” and 10 by “wellbeing”. For evaluating perceived chemotherapy-induced side effects in patients, 0 was accompanied by “without symptoms” and 10 with “most intense symptoms”. Similar VAS scales have been validated for stress [46], pain [47], or wellbeing [48] and an adaptation of the current VAS scales was used in a previous study about group music therapy in the hospital setting [49]. For the adaption, new questions were integrated, but the overarching structure was kept the same. In addition to the VAS, the post-intervention questionnaires included a section in which participants could leave personalized comments and suggestions. Figure 1 shows the pre-intervention questionnaire and Fig. 2 shows the post-intervention questionnaire.

Data was analyzed using the statistical software GraphPad Prism (version 9.0). As the scores were ordinal variables and did not meet the assumptions required for a parametric test, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed to compare the VAS score differences before and after group music therapy. The results were analyzed using the minimum clinically important difference (MCID), calculated with Cohen's d effect size [50]. This measure of change is derived by subtracting the mean pre-intervention scores from the mean post-intervention scores and dividing the result by the standard deviation of the pre-intervention scores. The effect size is a standard measure that represents the number of standard deviations the scores have moved from pre-intervention to post-intervention. An effect of 0.2 indicates a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. Therefore, we set the MCID threshold for Cohen’s d by multiplying the baseline standard deviation by 0.2.

The intervention description follows the guidelines for reporting music-based interventions [51]. Between April 13th and October 14th, 2022, group music therapy sessions took place twice a week on Wednesdays and Fridays from 9:30 am to 10:15 am and were led by two certified music therapists. Upon arrival, the musical instruments were cleaned according to a previously published cleaning and disinfection protocol [52]. Then, the music therapists individually asked each patient and caregiver if they would like to participate in the music therapy group, provided information about its goals, and explained the procedure. Participation was strictly voluntary. The nursing staff helped participants to get out of their cubicles and sit down in a chair that had been previously placed in a circle at a free space on the chemotherapy floor. The infusion pumps were placed beside the patients, and chemotherapy continued normally during music therapy. Once the group was set up, the music therapists briefly welcomed the participants, asked about current mood states, and explained the aims of using music during chemotherapy. Each session lasted about 45 min and was designed to provide participants with self-care strategies involving music. The group music therapy sessions consisted of three phases:

Forty-one group music therapy sessions were held between April 13th and October 14th, 2022, with 235 participants (166 patients and 69 caregivers). Pre-intervention questionnaires were filled out by 143 patients and 54 caregivers (n = 198), and post-intervention questionnaires were filled out by 141 patients and 51 caregivers (n = 192). 88 patients and caregivers left comments, observations, or suggestions on the post-intervention questionnaire.

Analysis of data from patients revealed a statistically significant reduction in anxiety levels (p < 0.001), stress levels (p < 0.001), and chemotherapy-induced symptoms (p = 0.003), as well as an improvement in well-being levels (p < 0.001). Calculated effect sizes were moderate for anxiety, stress, and well-being levels, and small for chemotherapy-induced side effects (see Table 1).

Analysis of data from caregivers/companions revealed a statistically significant reduction in anxiety levels (p < 0.001) and stress levels (p < 0.001), as well as an improvement in well-being levels (p = 0.009). The effect analysis showed a large reduction in anxiety and stress levels and a moderate effect on well-being levels (see Table 2).

Comments made by participants

The post-intervention questionnaires included 88 written comments that patients and caregivers left at the end of the session, corresponding to 45.83% of the participants. After reading each comment, they were grouped into three broad main themes (all direct quotes in the text have been translated from Spanish to English by author JT-M):

It should be noted that the participants could address more than one theme within each written comment.

Coping

A big part of participants’ comments made note of how the music therapy group helped improve physical side effects and their overall mental health and wellbeing. Common themes included enhanced relaxation, the use of music as an effective strategy to distract themselves from the chemotherapy routine, positive mood changes, and a more pleasant treatment experience. Patients and caregivers also noted how the relaxation and self-care strategies experienced during the music therapy group sessions could be used beyond their time at the hospital.

“Music therapy provides such relaxation and helps us forget about the symptoms we’re experiencing.”

“This is very relaxing for patients; you forget about everything that your treatment process entails.”

“Excellent educational experiences to be replicated at home. Thank you.”

Gratitude

Many comments left by patients and caregivers reflected an expression of appreciation for the group sessions. Often, gratitude was expressed in terms of comfort, taking into account the emotional and mental wellbeing of the participants, and connected to the ideas of humanization and support patients and caregivers experienced during the music therapy groups.

“The group helps provide us with comfort and lifts our spirits allowing us to take our minds off our diagnoses.”

“Excellent support. I congratulate you on your warm, humanizing attitude; you transmit peace and tranquility. Please continue to accompany us, your presence is important as we face this illness.”

Recommendations for the music therapy group

As the comments section of the questionnaire also aimed at gathering suggestions and feedback about the group itself, its content and structure, participants also left comments regarding the duration and frequency of the group. Many expressed the wish for the group sessions to last longer or to be provided on a more regular basis.

The results of the group music therapy sessions showed a statistically significant improvement in anxiety, stress, and wellbeing levels in patients and caregivers. Additionally, patients also reported a decrease in the intensity of chemotherapy-induced side effects. This is in line with previous research indicating that music-based interventions can improve overall mental health (e.g., [40, 42]), reduce anxiety (e.g., [38, 39]), and nausea, vomiting, and pain (e.g., [28, 41]). While our results should be interpreted with caution due to the absence of a standardized measurement instrument, they are of great pertinence and have several implications for music therapy practice in this setting.

As previously reported, chemotherapy can negatively affect the physical, mental, social, emotional, and spiritual domains of patients [16,17,18]. The adverse impacts of chemotherapy on mental health of patients can affect treatment adherence, and even more markedly so in patients with previously diagnosed mental illnesses [53]. A recent study found that patients with mental health difficulties were more likely experience physical comorbidities and hospitalizations during the first year after diagnosis [54]. Conversely, lower levels of depression and anxiety, increased social support, and participation in mental health programs can support treatment adherence and decrease mortality in cancer patients [55, 56].

Interestingly, the results of our study revealed that caregivers experienced higher levels of stress and anxiety and lower levels of wellbeing at baseline than when compared to the patients themselves. This could suggest a need for further exploration into the mental health of caregivers of oncology patients. Recent meta-analyses showed that the combined prevalence of depression and anxiety among caregivers of cancer patients is around 42%, with female caregivers being more affected than male caregivers [57, 58]. In line with our own results, psychoeducational interventions for caregivers have been shown to reduce anxiety levels in the short term and improved physical health three months post-intervention [59].

While music therapy has a long tradition in oncology settings, it is still a relatively scarce regular therapeutic offer during chemotherapy. One of the few group interventions using music was reported by Chen et al. [60], in which certified group therapists facilitated music-listening of pre-recorded music. An integrative music therapy group session using group singing, relaxation and picture visualization, and creative journaling was reported by Romito et al. [43]. The lack of more group music therapy interventions during chemotherapy is surprising, as its implementation is relatively simple and easily replicable if the physical space is adequate for bigger gatherings. The active participation of both patients and caregivers is a distinctive feature of the music therapy group, which allows for participants to get to know each other, exchange coping strategies, and foster interpersonal relationships.

Being the first study of its kind in Colombia, the results serve as preliminary evidence of music therapy’s potential to support patients and caregivers during chemotherapy. The positive feedback from staff and participants further highlights the feasibility of implementing music therapy groups in this setting. Since cancer patients belong to one of the fastest growing medical populations worldwide, the implementation of complementary therapies that aim at improving mental health and wellbeing are paramount, both for patients and for their caregivers.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a non-prospective study without a parallel control group. Thus, the results need to be interpreted with caution and cannot be generalized. Considering this limitation, a prospective multi-site RCT on group music therapy during chemotherapy is currently in the recruitment phase [61]. Second, the music therapy groups were part of regular clinical practice, allowing participants to join once or multiple times throughout their chemotherapy cycle; no information was collected regarding whether participants attended once or on several occasions. Third, the groups were not matched according to sociodemographic characteristics, medical status, type of cancer, or treatment phase, and thus differential analysis on potential confounding variables was not conducted. Future research should explore moderators and mediators of music therapy outcomes to more effectively individualize interventions. Fourth, the music therapists who led the sessions were also responsible for distributing and collecting the questionnaires. While the VAS scales were self-reported, this could nevertheless have resulted in potential bias. Fifth, in this study the supplementary qualitative comments of participants were grouped into broad themes after reading them various times, but no structured qualitative method was used for further analysis of the data. And sixth, although the number of group sessions (n = 41) and participants (n = 192) is higher than in most previous studies, it represents only approximately 6–10% of the patients who receive chemotherapy at the Cancer Instituted each year, limiting the generalizability of the results to a broader community of patients and caregivers.

Music therapy should be considered as a valuable complementary therapeutic option during chemotherapy. Besides patients, caregivers also need targeted support programs to mitigate the emotional impact of their role and enhance their overall wellbeing. It is crucial to conduct prospective multi-center studies with parallel group designs to confirm these preliminary findings and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how to optimize music-based interventions and therapies for the benefit of oncology patients and their caregivers.

All data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

No funding has been received for this study.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, CCEI-16508–2024, on June 18th, 2024. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the interventions and data collection. The study fully adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Salgado-Vasco, A., Torres-Morales, J., Durán-Rojas, C.I. et al. The impact of group music therapy on anxiety, stress, and wellbeing levels, and chemotherapy-induced side effects for oncology patients and their caregivers during chemotherapy: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Complement Med Ther 25, 124 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-025-04837-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-025-04837-7