BMC Public Health volume 25, Article number: 1172 (2025) Cite this article

Dentists are prone to a variety of occupational health problems and are at a high risk of workplace violence due to the nature of their dental practice. The aim of this study was to assess the state of occupational health and the prevalence of workplace violence among dentists in China. Additionally, this research endeavored to offer practical recommendations for Chinese dentists and relevant institutions based on the findings.

The survey was conducted based on a sample of 1109 dentists from China as respondents to an electronic questionnaire survey. This self-reported questionnaire encompassed 14 distinct types of injuries, 28 specific diseases, 11 symptoms of sub-health state, and 3 categories of workplace violence.

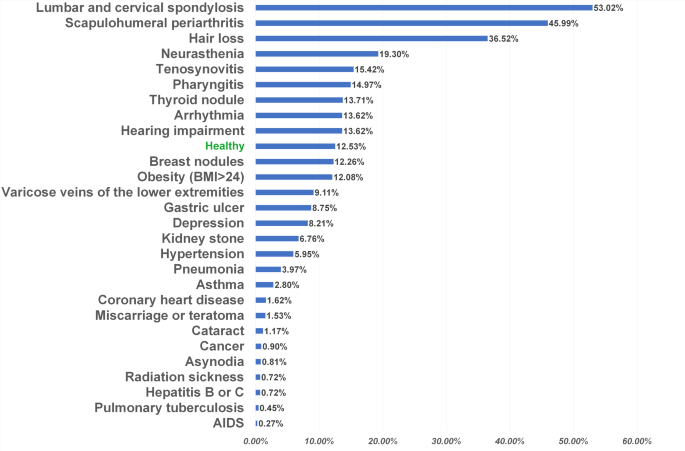

In dental practice, the most common injuries are needlestick incidents and falls, each affecting 54.28% of dentists. Conditions like lumbar and cervical spondylosis, along with scapulohumeral periarthritis, are prevalent, with 53.02% and 45.99% of dentists reporting these issues, respectively. Our univariate analysis highlighted significant health disparities among dentists, influenced by gender and department. Additionally, our findings underscore the harsh reality of verbal, physical, and sexual harassment faced by Chinese dentists, which has a profound negative impact and is met with woefully inadequate protective measures.

Chinese dentists face significant physical and psychological stress, further exacerbated by verbal abuse, physical violence, and sexual harassment. It is imperative that hospitals, clinics, and governmental agencies step up to their responsibilities by fostering a secure work environment for Chinese dentists.

Occupational health is a multidisciplinary and comprehensive approach which aims to protect and promote the health of a worker. Occupational health problems represent a significant concern in the field of public health and workplace safety. Dentists are susceptible to a range of occupational health issues stemming from dental practice, which encompass physical, biological, chemical, and psycho-social risks [1]. The occupational health-related problems are induced or aggravated by the work specificity and greatly affects the health of dental professionals [2]. According to the U.S. national health survey based on the Occupational Information Network (O*NET), dentists are at the pinnacle of professions with the greatest health hazards [3]. Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), eye injuries, vibration-induced neuropathy, and psychological conditions are some of the poor health outcomes due to occupational health issues. Contact-dermatitis, hearing loss, and toxicity from materials used in dental practice have been noted as significant occupational hazards. Other risks include incidents due to exposure to infectious diseases, radiation, and noise, and allergy to dental materials [4]. Despite these well-documented risks, research on occupational injuries among dental practitioners in China remains strikingly scarce, which hinders a comprehensive understanding and effective prevention of these occupational health issues.

Workplace violence is deemed illegal, yet it remains a daily occurrence for numerous healthcare professionals, substantiating workplace violence is a pervasive problem worldwide in the healthcare sector [5]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), such violence can have far-reaching consequences, impacting not just the individuals directly involved but also the broader work environment, coworkers, employers, families, and society. Violence in the healthcare workplace manifests in various ways, and a consensus definition of healthcare workplace was agreed upon and proposed in 2016. This definition encompasses verbal abuse, property damage or theft, physical abuse, sexual harassment, and bullying [6].

Dentistry faces a higher risk of workplace violence in hospital and clinic settings compared to other healthcare fields, largely due to the typically congested nature of dental practices. Numerous studies on workplace violence have been conducted for medical doctors [7,8,9,10], nurses [11,12,13], mental health staff [14] and emergency department staffs [15,16,17], there is a noticeable scarcity of research dedicated to dental professionals [10]. The number of dentists in China has been increasing in recent years. According to the China Health Statistics Yearbook, in 2021, the number of dentists in China reached about 311,000 [18]. However, to the best of the researchers’ knowledge, there is a notable absence of data regarding workplace violence in the dental sector in China in the published literature.

Given this context, we intend to conduct a voluntary online questionnaire survey to assess the state of occupational health and the prevalence of workplace violence against Chinese dentists. This initiative is designed to address the existing research void and to lay the groundwork for evidence-informed to offer practical recommendations for Chinese dentists and relevant institutions.

The present study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ninth People’s Hospital of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (SH9H-2024-T311-1). All procedures were performed in accordance to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and conformed to the STROBE guidelines. Participants who complete and submit the questionnaire are deemed to have provided their informed consent.

We conducted an online survey targeting dentists in China, utilizing a self-reported questionnaire. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: 1. Dental practitioners or assistant practitioners (i.e., professionals holding a nationally recognized dental practice certificate) in China who fully understand the content of this study and voluntarily participate in it. 2.All subjects must have at least one year of experience in clinical practice. 3.Participants with incomplete questionnaires will be excluded from the analysis.

Based on the available and relevant literature a Chinese version questionnaire to assess the overall occupational health status and experiences of workplace violence among dentists was designed [2, 19,20,21]. This study referenced several Chinese degree theses and employed a questionnaire that is nearly identical to those previously validated. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for overall scale were all above 0.9. A pilot study was conducted to confirm the clarity of the questions and their ease of response. The questionnaire was structured into 3 sections:

The first section focused on socio-demographic characteristics, encompassing details including the nature of the institution, gender, age, department, professional title, and years of work experience.

The second section addressed occupational health-related issues over the past 12 months, including a sub-health self-assessment form, a work-related injury form and a work-related disease form:

sub-health status (%) = the number of people who present more than five symptoms/ the number of entire samples.

The third section was dedicated to surveying workplace violence incidents in hospitals over the past 12 months, categorizing three forms of violence: verbal, physical, and sexual harassment. This section comprehensively examined various facets of workplace violence against dentists, including the frequency of incidents, the specific locations where they occurred, the individuals responsible for the aggression, the motives behind these acts, the strategies dentists employed to manage such situations, and the psychological impact on the dentists.

The sample size for this cross-sectional study was calculated based on a single proportion formula. We analysed the first 200 completed questionnaires, and the results showed that the prevalence of sub-health was approximately 50%. Using the PASS 15 software, the following parameters were set: Confidence Interval Formula: Simple Asymptotic (selecting the normal approximation method); Interval Type: Two-Sided (selecting a two-sided confidence interval); Confidence Level (1-α): 0.95 (a confidence level of 95%); Power(1-β): 90%; P (Proportion): Enter the expected prevalence of 50%; Enter the Alternative Difference as 0.05. The final calculated sample size is 1047.

We established construct validity to further verify the questionnaire’s validity. Specifically, we conducted a correlation analysis between the scores of sub-health in the questionnaire and the self-assessed health evaluations by dentists.

The database was established using Epidata, and statistical data analysis was conducted with SPSS 21.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The primary methods of analysis included descriptive statistics, with the use of incidence rates and composition ratios for statistical description. For continuous data, independent samples t-tests were utilized, while categorical data were evaluated using chi-square tests. Logistic regression analysis was employed to investigate the occurrence of sub-health conditions. All statistical analyses were conducted as two–sided, with P < 0.05 was regarded as statistical significance.

We collected a total of 1,203 online questionnaires among Chinese dentists. After the screening process, 1,109 dentists were included in our analysis (Online Appendix Fig. 1). Dentists from nearly all regions of the country participated in this survey (Online Appendix Fig. 2). Among the total number of dentists surveyed, 372 (30.84%) were male and 767 (69.16%) were female. Nearly three-quarters of the respondents worked in public hospitals, while the remaining quarter worked in private hospitals. Approximately half of the participants were general dentists, and one-quarter were paediatric dentists. The average age of these dentists was 37.63 years, with an average of 12.97 years of working experience (Table 1).

Dentists reported various types of injuries and their frequency (per year) related to their occupational activities (Table 2). More than half of the dentists surveyed (54.28%) reported experiencing needlestick or fall-over injuries, which were the most frequently encountered among all reported occupational injuries. The average number of needlestick injuries per year for the entire sample was 2, while for only affected individuals, the average was 2.46 times per year. Approximately one-third of the dentists reported experiencing rashes, allergic dermatitis, or chapped skin. Some dentists even suffered from these injuries throughout the year. Additionally, a small proportion of dentists reported injuries directly caused by their patients, including bites, scratches, or beatings. These injuries underscore the threats that dentists face from their patients, despite the low incidence of such events.

The surveyed dentists reported various diseases related to their occupation, including both acute and chronic conditions, whether non-fatal or fatal. The prevalence of occupational diseases among dentists surveyed in this study was depicted in Fig. 1. Among these, lumbar and cervical spondylosis and scapulohumeral periarthritis were the most frequently reported, accounting for 53.02% and 45.99% of the dentists, respectively. These conditions likely resulted from prolonged immobility and the physically demanding postures required in dentistry, which contribute to joint and musculoskeletal strain. In addition to these, tenosynovitis (15.42%) and varicose veins in the lower extremities (9.11%) may also stem from similar occupational demands. Over one-third of the dentists also reported hair loss, a condition often linked to excessive mental stress. Neurasthenia (19.3%) and depression (8.21%) were also reported, likely due to similar stress-related etiologies. A small number of dentists reported infectious diseases such as hepatitis B or C, pulmonary tuberculosis, and AIDS, which, despite their low incidence (0.27-0.72%), could have serious consequences. Furthermore, ten dentists (0.9%) reported cancer, a fatal condition attributed to their occupational hazards.

The higher the number of positive sub-health items, the worse the self-assessment of overall health (r = 0.400, p < 0.001); additionally, the higher the number of positive sub-health items, the greater the impact of self-perceived health on overall life (r = 0.406, p < 0.001), which demonstrates that the questionnaire possesses good construct validity (Online Appendix Table 1). More than half (54.19%) of the surveyed dentists were classified as being in a sub-health status overall (Online Appendix Table 2). Among the sub-health symptoms that occurred two or more times per week, neck and shoulder pain, dizziness, and blurred vision were the most prevalent, affecting 73.40% of the dentists. In other words, approximately three out of every four dentists reported issues with their lumbar and cervical spine. Other common sub-health symptoms among dentists included a lack of concentration (61.32%), easy physical fatigue and shortness of breath (58.43%). Nearly half of the dentists also experienced sub-health conditions such as irritability, insomnia, poor sleep quality, and significantly increased hair loss at least two or more times per week. In comparison, the prevalence of hypoglycaemia symptoms among dentists was relatively lower.

The analysis revealed statistically significant differences in the prevalence of sub-health status among dentists based on gender and department (Table 3). However, no statistical significance was observed in relation to the affiliated unit, professional title, age, or years of work experience. An ordinal multi-classification logistic regression model was constructed, incorporating variables such as affiliated unit, gender, dentists’ departments, professional title, age, and years of work experience. The ordinal logistic regression analysis indicated that paediatric dentists had a 1.40 times higher probability of being in a sub-health state compared to those in general departments (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.036–1.879; p = 0.028) (Online Appendix Table 3).

Dentists reported various types of violence they faced, including the sources, causes, their responses, and the impact of such violence on them (Table 4, Online Appendix Tables 4, 5 and 6). Over half (59.69%) of the dentists indicated that they experienced verbal violence more than once a year on average. Among these, 12.71% of the dentists even endured this form of violence an average of three or more times a year. The average annual proportion of dentists who suffered from physical violence and sexual harassment was 4.87% and 1.89%, respectively. The vast majority (over 90%) of the reported violence originated from patients or their companions, with only a small fraction attributed to medical staff.

Approximately half of the dentists surveyed believed that the reason for patients using abusive language was due to patients’ irritable personality (58.46%) and the dentist’s refusal of unreasonable requests from patients (43.96%) (Online Appendix Table 4). Approximately 1/2 to 1/3 of dentists believed that the reason why patients had verbal violence towards them was due to long waiting time (29.79%), high medical costs (27.64%), insufficient medical communication (25.23%), dissatisfaction with the treatment effect (25.23%) or dissatisfaction with the dentists’ attitude (19.79%). About three quarters (73.56%) of dentist would explain the reason patiently when verbal violence occurred. Half (42.15%) of the dentists said they would endure this violence. Some of the dentists (10.73-26.28%) would seek help from their leaders, colleagues or security personnel. Only 16.01% dentists felt nothing about this situation. However, negative emotions easily appeared when verbal violence occurred, including decreased work enthusiasm, aggrieved, depression, the thought of changing careers or resignation. We also surveyed the reason of the physical violences and sexual harassment, how the dentist response and the violences’ impacts on dentists (Online Appendix Tables 5 and 6).

This study presents a preliminary survey that pays particular attention to the prevalence of various occupational health issues—such as sub-health states, injuries, and diseases—and workplace violence among dentists in China. We have also established a correlation between risk factors and the sub-health status of dentists, highlighting these factors as influential components. While the prevalence of occupational health issues and workplace violence has been documented across various professions, comparable studies focusing on dentists are relatively scarce. Given the physically demanding nature of their work, characterized by inactivity, sedentary lifestyles, stress from working in enclosed spaces, and extended working/clinical hours, dentists are particularly susceptible to stress and related health complications. The findings of this study will aid in identifying potential causes of occupational health concerns and violence, potentially contributing to the development of preventative measures.

Owing to the unique working conditions and the frequent use of numerous sharp instruments, such as needlesticks, scalpels, and dental files, dentists are at risk of stabbing incidents, which regrettably can occur during clinical procedures [22]. This study reveals that over half of the dentists experienced needlestick injuries, which were the most frequently reported occupational injuries. According to the WHO, an estimated 3 million of the 35 million healthcare workers worldwide are exposed to needlestick injuries each year [23]. Our literature review indicates a paucity of comprehensive global statistics regarding the prevalence of needlestick injuries among dental professionals. These injuries, which can occur with sharp instruments such as needlesticks, scalpels, and dental burs, are not only possible but, regrettably, are a reality during the clinical practice of dentistry [24]. Multiple articles refer to approximately 20 types of infections that are transmitted most commonly through sharp objects injuries, especially HIV, HBV, and HCV [25]. Correspondingly, our study revealed that among the 1,109 dentists surveyed, 8 reported cases of hepatitis B or C, and 3 reported AIDS. In reality, the prevalence of self-reported occupational exposures to bloodborne pathogens is likely higher than what is officially recorded. This underreporting may stem from several factors, including a fear of stigmatization, concerns about the confidentiality of their data, such as serological test results, and the belief that the reporting process is cumbersome and time-consuming.

The health status of dentists is a growing concern, with musculoskeletal disorders and stress being the most frequently reported issues [2]. Notably, only 12.53% of dentists reported no occupational diseases. Conditions such as lumbar and cervical spondylosis, scapulohumeral periarthritis, and tenosynovitis top the list of prevalent musculoskeletal disorders. The reported prevalence of these disorders among dentists is alarmingly high, exceeding 80% in the majority of studies [4]. Even though dental professionals are cognizant of the proper ergonomic posture, they often find it challenging to maintain such posture due to the high physical demands of their work [26]. Based on the results of previous study, static awkward working posture was shown to significantly increase the odds of musculoskeletal disorders [4]. Furthermore, occupational diseases among dentists are often precipitated by intense mental stress, leading to conditions like hair loss, neurasthenia, and depression. A study conducted in the UK reported that 42% of surveyed dentists exhibited high levels of emotional exhaustion [27]. The main factors that caused significant stress among dentists were maintaining high levels of concentration and constant interaction with people [28]. National Health Service (NHS) offers occupational health services for doctors and dentists to maintain physical and mental health and well-being by recording work-relatedness and fitness, as well as offering appropriate referrals. However, it has been observed that doctors rarely seek occupational health services, often only doing so when mandated by regulatory requirements [29]. There is a pressing need for the broader dissemination and effective implementation of policies designed to enhance the physical and mental well-being of dentists. Clinical guidelines for sub-health released by the China Association of Chinese Medicine pointed out that the sub-health is one that shows declines of vitality, physiological function and capacity for adaptation [30]. Over the years, the concept of sub-health has been widely accepted in many other countries such as Canada and Australia [31, 32]. Our results indicated more than half of the dentists were under sub-health status in overall, characterized by both physical and psychological distress. The female dentists were more prone to sub-health state. The principal gender issues identified were unequal representation of female doctors in leadership positions and in some specialties, gender-based discrimination, work-life imbalances, socio-cultural norms and lack of professional development opportunities [33]. Besides, paediatric dentists are more easily under sub-health state. Paediatric dentists may experience more stressors in their work environment including time-related pressures, less co-operative young patients, anxious parents and heavy workloads. According to the American Dental Association, paediatric dentists see almost twice as many patients per week as general dentists (excluding hygiene visits) [34]. Compared with general dentistry, paediatric dentistry is a fast-paced environment. Contrary to our expectations, there was no correlation between the sub-health status of dentists and their age or years of professional experience. While younger resident dentists, despite their physical vigour, may face heightened psychological stress due to their inexperience in performing skilled operations, patient bias, lack of experience in managing the intricate dynamics with patients, and the intense competitive environment [35]. Burnout among dentists is a significant and widely recognized issue, affecting their mental health, job satisfaction, and overall well-being. Recent studies have shown that burnout is highly prevalent among dental professionals, with high levels of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment reported. Additionally, burnout can negatively impact patient care and professional relationships, highlighting the need for targeted interventions to address this issue [36,37,38].

The global literature on occupational violence among dentists is scarce, with fewer than 10 reports available [39,40,41,42], and in China, this area remains largely unexplored. Occupational violence, in any form, should not be acceptable, irrespective of the frequency of its occurrence [43]. Personal safety should be a priority in any professional environment. According to the Society for Human Resources Management, one in seven employees in the US workforce feels unsafe in their workplace [39]. Prior to the pandemic in 2020, 60% of the health-care workforce had experienced verbal or physical abuse from patients. In the following two years, this prevalence rose to 89% reporting workplace violence from patients, family members, or colleagues [40]. In the United States, some states, such as California, have required nearly all employers to develop and implement written workplace violence prevention plans since July 1, 2024 [41]. In Australia, research has recommended addressing workplace violence through improved healthcare management [41]. In recent years, the Chinese government has also increased its focus on workplace violence in the healthcare sector, proposing measures such as improving policies and regulations, and establishing and perfecting reporting and punishment mechanisms [42]. Our findings reveal the dire situation of professional violence faced by dentists in China, characterized by a high incidence of violent events and a range of severe consequences, including fatalities. Violence in the workplace is associated with various negative consequences. Some dentists report a diminished passion for their work, and in extreme cases, the emergence of suicidal ideations. Dental professionals usually take no action against abuse due to perpetrator-target relationships [44]. The majority of dentists opt for patience and endurance, choosing to avoid confrontation. A mere minority seek intervention from law enforcement or psychological support services. There is an evident absence of institutional protocols and guidelines for addressing this issue effectively. To date, no interventional studies within the field of dentistry have examined the impact of awareness and educational initiatives on the detection and reporting of abuse incidents [45].

Findings of the present study should be contextualized within several study limitations. Firstly, the absence of systematic sampling across all registered dentists in China may have limited the generalizability of the study’s participants. At the same time, the lack of a sampling method increased the risk of bias. The survey results might be influenced by the characteristics of specific groups, thereby deviating from the true situation that Chinese dentists faced. Secondly, the data on occupational diseases in our study were primarily based on self-reports. Self-reporting is a common method in occupational health studies, yet it may introduce biases. However, its validity has been well-documented, particularly among dentists, as a reliable way to capture symptoms and perceived health issues when standardized diagnostic protocols are lacking [2]. Besides, the study did not account for other pertinent risk factors, such as physical exercise, smoking habits, and other lifestyle elements, which could potentially skew the precision of the occupational health assessments. Nonetheless, this report marks the inaugural investigation into the comprehensive occupational health status and experiences of workplace violence among dentists in China. Regrettably, the study reveals a notably high prevalence of occupational issues and workplace violence against Chinese dentists, exerting a substantial impact on their well-being. However, the legislation system in China is not equipped to deal with this situation because of low rates of occupational health screenings designed to detect conditions arising from workplace activities, as well as flaws in the national occupational information network system [46].

A call to action is imperative. Chinese dentists face significant physical and psychological stress, further exacerbated by verbal abuse, physical violence, and sexual harassment. Hospitals and clinics are strongly urged to take on the critical role of ensuring a secure working environment for dentists by implementing adequate precautionary measures, enhancing workplace policy improvements, and supporting legal reforms to intensify the monitoring and assessment of the health status of dental professionals. Governmental entities at various levels should be actively involved in the revision and enhancement of occupational laws and health regulations; investigate and promote facilities that would benefit dentists’ health; strengthen the surveillance and reporting systems for preventing and controlling occupational health issues and monitoring workplace violence; and develop and implement comprehensive dentist training programs to enhance workplace safety and professional preparedness.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- MSDs:

-

Musculoskeletal disorders

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

The authors acknowledge all participants in this study.

This work was supported by ‘Paediatric Stomatology’, a key course project of ideological and political demonstration at the School of Stomatology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (JYJX01202202).

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ninth People’s Hospital of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (SH9H-2024-T311-1). This study is an online questionnaire survey, and the declaration at the beginning of the questionnaire states that those who fill in and submit the questionnaire are considered to have given informed consent.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Yu, L., Zhu, C. & Wang, J. A preliminary survey of occupational health and workplace violence among 1109 Chinese dentists: a call to action. BMC Public Health 25, 1172 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22383-2