BMC Psychiatry volume 25, Article number: 512 (2025) Cite this article

Despite being crucial in ensuring the best treatment outcomes, adherence status is frequently overlooked in comprehensive chronic care. Thus, the present study critically evaluates, integrates, and summarizes psychotropic medication non-adherence and its determinants among patients with mental disorders in a resource limited life trajectories to inform policy and future research.

Systematic review and meta-analysis following the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement was conducted. PubMed (Medline), CINAHL, PsychINFO, EMBASE, and Google Scholar databases were comprehensively searched to retrieve published and grey literature from index inception to October 2024. Observational original studies focused on the magnitude of psychotropic treatment non-adherence and its predictors were eligible for inclusion. Risk-of-bias was assessed using Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) criteria. Protocol was pre-registered at PROSPERO with a reference number of CRD42024578766.

Twenty-three studies (n = 23, 359) were included, 22 of them in the quantitative analysis. The pooled prevalence of non-adherence was 46% (95% CI: 40%-52%, I2 = 96.95%). Subgroup analysis revealed that non-adherence was higher among patients with major depressive disorder (40.43%, I2 = 98.87%). Sociodemographic factors (aOR = 1.58, I2 = 87.13%), patient-related factors (aOR = 1.47, I2 = 25.62%), lack of insight (aOR = 1.24, I2 = 72.12%), negative attitude towards the treatment (aOR = 1.78, I2 = 0.00%), poor social support (aOR = 1.49, I2 = 82.55%), self-stigma (aOR = 1.97, I2 = 30.70%), and drug-related factors (aOR = 1.42, I2 = 64.16%) were the predictors. Substance use was identified as a protective factor for adherence (aOR = 0.84, I2 = 99.97%).

Altogether, we discovered that psychotropic treatment non-adherence among patients with psychiatric disorders was quite common. This analysis may serve as a high-grade ore for policymakers, though it must be interpreted with caution due to significant heterogeneity. Notwithstanding stringent methodology, depending on cross-sectional studies limits its clinical guidance.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM- 5-TR), “a mental disorder is a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning, usually associated with significant distress or disability in social, occupational, or other important activities.” [1]. Mental disorders are a growing crisis globally, ranking among the top 10 causes of morbidity. In 2021, they accounted for 13.9% of the global disease burden and 17.2% of total years lived with disability, with anxiety and depression being the most prevalent across all age groups and regions [2]. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) due to mental disorders rose from 125.3 million in 2019 to 155 million in 2021, with the proportion of global DALYs attributed to mental disorders increasing from 4.9% to 5.4% over the same period [3, 4]. Major psychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, and anxiety disorders had a prevalence of 332 million, 23.2 million, 37.5 million, and 359 million cases, respectively by 2021 [4].

Nearly three-quarters of the global mental health burden falls on low- and middle-income countries like Africa, with Ethiopia facing even greater DALY impacts due to strained healthcare systems [5]. Untreated mental illness exacerbates long-term disability due to limited access to care, ongoing stigma, poverty, political polarization, active war between the government and rebels, the novel coronavirus pandemic, and unemployment in the study area [6]. In Ethiopia, mental illness is the leading non-communicable disorder in terms of burden measured in DALYs, often underreported due to stigma and practical obstacles [7,8,9]. The prevalence of common mental illnesses in the Ethiopian general population was as high as 21.58% and reaches 36.43% in comorbid conditions [10].

The era of "no sustainable development without mental health" has begun [11], as achieving United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3 (good health and well-being for all) is impossible without prioritizing mental health [12], despite ‘no health without mental health’ being an important ambition. The Ethiopian Ministry of Health has made considerable progress in integrating mental health care into the primary health care system through the execution of the national mental health policy. Nonetheless, restricted access to these treatments continues to pose a significant difficulty in effectively addressing mental health issues [13].

Pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are the two first-line treatment options for mental disorders [14]. Despite medications being crucial for preventing relapse and enhancing the quality of life for psychiatric patients, ensuring the treatment efficacy remains a major challenge. This is determined by various different factors, above all, non-adherence to the treatment prescribed, in particular a crucial, but often overlooked, aspect of holistic chronic care. Although adherence is central to pharmacotherapy, it is often poor in chronic medical illnesses, even worse in severe mental disorders yet [15]. Suboptimal medication adherence is a pervasive global concern and constitutes a significant therapeutic challenge that has been called an “invisible epidemic” with respect to human suffering. Globally, non-adherence rates in mental health treatment have been reported to range from 40 to 60% [16]. In developing nations, like Ethiopia, the problem of inadequate adherence is more pronounced and very divergent, ranging from 26% to 84.7% [17, 18].

Non-adherence: driving treatment failure, fueling healthcare costs, and worsening health outcomes such as relapse, worsening of symptoms, increased hospitalizations, suicide [19] and higher mortality rate adverse consequences, posing a serious threat to effective disease management, functional decline, and patient well-being [15, 20,21,22,23]. It also plays a role in 21–37% of preventable adverse drug events [24]. Approximately 125,000 deaths and $100 billion to $300 billion in yearly medical costs are attributed to non-adherence in the United States [25].

Barriers to adherence span multiple levels, including drug side effects, stigma, negative attitudes, lack of insight, cognitive issues, socioeconomic factors, healthcare access, and complex treatment regimens [26, 27]. To devise effective interventional strategies for improving medication adherence among psychiatric patients, a thorough understanding of the magnitude of non-adherence and its predictive factors is essential. This can only be achieved through comprehensive facts derived from robust research evidence. Despite some preliminary, inconclusive researches, no comprehensive reviews or meta-analyses have been performed so far to support evidence-based medicine in mental health clinics or to guide policymaking in this area. To address this knowledge gap, we performed this systematic review and meta-analysis.

The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [28] and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were used for conducting and reporting this systematic review and meta-analysis [29] (S1 Checklist). The protocol was pre-registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024578766) to enhance transparency, reduce reporting bias, and avoid unnecessary duplication.

This review included observational (cross-sectional and cohort) studies from inpatient and outpatient settings in Ethiopian hospitals.

Inclusion criteria

This review included observational (cross-sectional and cohort) studies on adult or paediatric samples, from inpatient and outpatient settings in Ethiopian hospitals. We did not restrict article publishing dates, language, or status to avoid dissemination bias. Theses and dissertations with full text were also considered. Study participants must have been on psychotropic medication. Indisputably, since there is no “gold standard” for measuring adherence behaviour we have included original studies reporting non-adherence status by any relevant strategies [30,31,32].

Exclusion criteria

Letters to the editor, commentaries, editorials, case series, case studies, conferences, case reports, and qualitative and quantitative review articles were ineligible.

Operational definitions

Severe psychiatric disorders mean schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), and major depressive disorder (MDD) based on this review.

Psychotropic drug treatment: refers to the use of medications that affect brain chemistry and influence mood, perception, behavior, or cognitive function. These drugs are commonly prescribed to manage psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, BD, schizophrenia, and other severe mental illnesses [11].

The electronic databases were queried using standard indexing procedures. Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), MEDLINE (via PubMed), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Web of Science were searched by investigators from inception to September 2024. The reference list of original publications and related review articles, theses, or dissertations discovered in the database search were also obtained manually. Google and Google Scholar were used to obtain grey literature. PubMed (Medline), EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL were searched with controlled vocabulary like medical subject heading search terms (MeSH terms), exact Emtree terms, CINAHL Subject Headings and free-text terms (key words) (S2 search strategy), which enables this systematic search to be robust, transparent and replicable [33]. The following search terms were used: “Medication *adherence”, “medication noncompliance”, “medication compliance”, “treatment attrition”, “treatment barriers”, “adherence barriers”, “treatment dropout”, “treatment *adherence”, “medication discontinuation”, “maintenance level of treatment”, “maintenance level of pharmacotherap*”, “medication *persistence”, “Drug Adherence”,"Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorder*","schizotypal personality disorder*", schizo*,"paranoi*", patient dropout, treatment refusal, depressive disorder, and depression, major depression, affective disorders, and dysthymic disorder; complian*, adheren*, pharmacotherapy, risk*, predictor*, associated factor*, influencing factor*, determinant* cross sectional study, cohort study, case–control study, follow up study,

Boolean operators ("OR"and"AND") were used to merge the search results, which were then saved in individual databases and exported to Endnote for referencing. Two authors (W.S.Z and T.A.M). The references were imported into Endnote Library version 20 after a literature search was conducted using multiple databases [34]. We culled the collection of duplicate citations. Subsequently, two authors (W.S.Z and T.A.M) undertaken the study selection process based on the pre-defined screening criteria in the study protocol. First of all studies were screened by the titles relevance. Subsequently, the abstracts of the selected articles were reviewed to identify pertinent articles. Then full texts of the selected articles were reviewed independently by the same two authors for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. Differences of opinion were sorted through mutual discussion and mediation by G.Y.T

This systematic review and meta-analysis has aimed to determine two main outcomes. The first outcome is the pooled prevalence of treatment non-adherence status among mental disorders. Treatment adherence, as given by the WHO, is “the extent to which a person’s behavior-taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes-corresponds with the agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider” [30]. Therefore, non-adherence is “a case in which a person’s behavior in taking medication does not correspond with agreed recommendations from health personnel” involving poor and suboptimal adherence status.

Different types of adherence measures have been used to evaluate adherence among patients with mental disorders. Due to the lack of a gold standard adherence measurement scale, we have included articles employing different techniques. The Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS), Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS), compliant fill rate (CFR) and authors developed questionnaires were adopted as a measure of medication adherence.

Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS- 8)

A widely used scale where patients answer eight questions about their medication-taking behavior. Responses are"yes"or"no"for items 1–7, with"no"scored as 1 and"yes"as 0, except for item 5, where"yes"is scored as 1 and"no"as 0. Item 8 had a 5-point Likert scale response option coded 0–4 (Never/Rarely (4), Occasionally (3), Sometimes (2), Usually (1), and Always (0)). The code (0–4) must be standardized by dividing the outcome by 4 to compute a cumulative score. A score of 8 indicates high adherence, 6 to 7 indicate medium adherence, and a score of < 6 indicates low adherence [35, 36].

Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS- 4)

A commonly utilized scale in which patients respond to inquiries regarding their adherence to drug regimens. This instrument comprises four dichotomous inquiries (yes corresponds to 0 and no corresponds to 1). The cumulative score varies from 0 to 4. A score of ≤ 2 signifies non-adherence, while scores > 2 are deemed adherent [27, 36].

Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS)

is a 10-item tool that asks patients to report how often they engage in non-adherent behaviors and their attitudes toward medication. A ‘No’ response for questions 1–6, 9–10 and an ‘Yes’ response for questions 7–8 indicates adherence. Interpretation Adherence (Score ≥ 6) and Non-Adherence (Score < 6): [37, 38].

Compliant fill rate (CFR) method

denotes the ratio of total fills that are compliant, meaning filled at timely intervals within a designated timeframe. Adherence was evaluated by comparing the quantity of supply days to the number of calendar days between refills. A prescription fill was deemed adherent if it occurred prior to the completion of the preceding prescription and no more than 20% of the drug remained with the patient [39, 40].

The second outcome is its predictors linked with non-adherence to psychotropic treatment among psychiatric patients. Explanatory variables predictive capacity was measured by the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) collected from the multivariate analysis of original studies.

W.S.Z and T.A.M appraised the quality of the studies employing the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality evaluation protocol for cross-sectional studies [41] and for qualitative studies [42]. Studies were deemed low-risk if they achieved a half score or above on the quality evaluation instruments. All articles that underwent critical appraisal were scored greater than 50% (S3 JBI score).

Two authors (W.S.Z and T.A.M) independently extracted all the necessary data using a standardized data extraction format prepared in Microsoft Excel 2016. All pertinent data included in the data extraction format were: demographic data (e.g., gender, age), first author’s name, year of publication, region, study design, sample size, quality of the included papers, tools for medication adherence assessment, data collection techniques, diagnosis criteria, non-adherence cut off points and prevalence of non-adherence, and standard error (SE) of the prevalence of non-adherence. Factors influencing non-adherence were systematically assessed by extracting and calculating the aOR, lower confidence interval (LCI), upper confidence interval (UCI), as well as their logarithmic transformations (logaOR, logLCI, logUCI) and the standard error of logaOR (SElogOR) for each variable, before exporting the data for analysis in STATA Version 17 [43]. (Additional file 1 & Table 4). If the included study reported the aORs of being adherent, we transformed them into aORs of non-adherence using the 1/aOR formula [41].

LCI was calculated employing Eq. 1:

$$\text{LCI} = e^{\log(\text{OR}) - Z_{\alpha/2} \cdot \mathrm{SE}}$$

(1)

while UCI was computed based on Eq. 2:

$$\text{UCI} = e^{\log(\text{OR}) + Z_{\alpha/2} \cdot \mathrm{SE}}$$

(2)

The formulas lnaOR (natural logarism of aOR), lnUCI (natural logarism of UCI), and lnLCI (natural logarism of LCI) were used to determine the logaOR, logUCI, and logLCI, respectively.

The SElogOR was computed employing Eq. 3

$$\mathbf{SElogOR}=\frac{\mathbf{InUCI}\boldsymbol-\mathbf{InLCI}}{2\ast\left({\displaystyle\frac{\mathrm{Z}\alpha}2}\right)}$$

(3)

at 95% CI while aOR was reported in the study [44]. Any divergence of viewpoint was duly acknowledged and addressed through consensus between the two reviewers, or alternatively, a third author, YAF, was served as an arbitrator. The SE for the prevalence was computed employing Eq. 4:

$$SE=\sqrt{p\ast\frac{1-p}n}$$

(4)

, where p stands for prevalence of non-adherence extracted from each original study n and n stands for the sample size of participants of each study.

All studies included in the review were described in a table comprising their main characteristics and outcome measures. The extracted data in Excel were exported to the software STATA (version 17.0) for analysis [43]. Given the clinical, methodological, and statistical heterogeneity in the original studies, a random-effects model using the DerSimonian-Laird (DL) method was applied to pool non-adherence prevalence [45]. This approach aligns with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (version 6.5), which advises against basing the choice between fixed-effect and random-effects meta-analysis solely on statistical tests for heterogeneity [28].

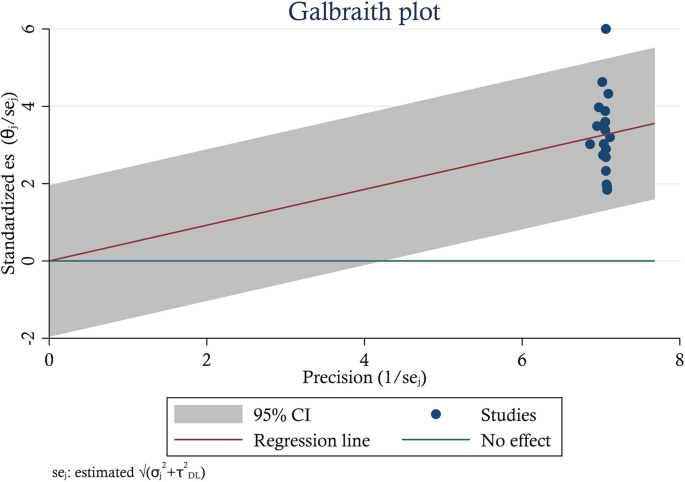

The presence of heterogeneity was assessed between included studies using both the graphical and statistical methods. From graphical methods, symmetry of the forest plot and Galbraith plot, and among statistical methods, Cochrane's Q test of heterogeneity and I2 statistics were employed. A Cochrane Q value indicates significant heterogeneity among studies if its P < 0.05. I2 statistics predict low, moderate, and high heterogeneity when it is above 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively [46]. The forest plot indicated heterogeneity when asymmetry occurred due to non-overlapping 95% CIs of point estimates; symmetry exhibited no heterogeneity between the studies. The Galbraith plot detects heterogeneity by assessing how studies vary around the regression line, representing the overall effect size. High heterogeneity is indicated by point estimates falling outside the CIs. Low-precision studies cluster near the origin, while higher-precision studies shift rightward along the x-axis. Subgroup analysis was conducted involving moderators that might influence the overall pooled point estimate. Random-effects DerSimonian Laird univariate meta-regression analysis was then applied to further explore whether individual study characteristics could explain heterogeneity for the non-adherence estimate.

A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to check the stability of the summary estimate following omitted individual studies. Small study effect and publication bias were used interchangeably in this study. Published studies may not accurately reflect the entirety of legitimate researches conducted. Because studies with negative results and involving a small sample size may not be published. This bias may jeopardize the trustworthiness of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, upon which evidence-based medicine greatly depends. A funnel plot, along with Begg’s and Egger’s regression tests, was employed to assess publication bias both qualitatively and quantitatively. The funnel plot was assessed for asymmetry using visual examination, as well as Egger’s and Begg’s tests; a significance level of P > 0.05 shows an absence of publication bias [47]. P-values < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant in all analyses undertaken.

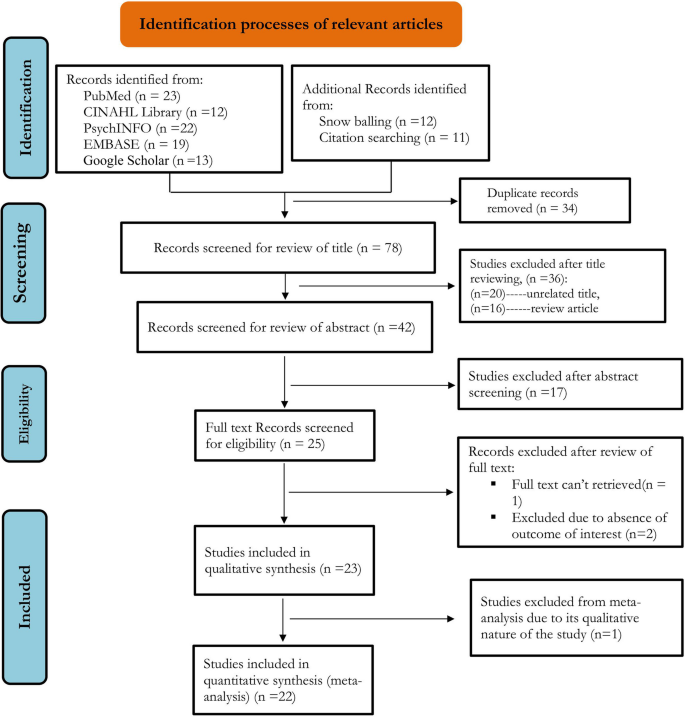

As per our pre-registered protocol (PROSPERO ID CRD42024578766), we searched different databases until September 2024. Using the search strategies defined previously, 112 studies were retrieved from different databases. Thirty four duplicates were removed. Of the 25 articles assessed for eligibility, 23 met the inclusion criteria and were included as pertinent to the objectives of this systematic review. Among them, 22 articles were involved in the final meta-analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the outcomes of the search, along with the reasons for exclusion during the study selection process. A risk of bias assessment was conducted among 23 eligible studies employing JBI criteria for qualitative and quantitative studies, as presented in (S3 JBI score), revealing that all of the studies had a low risk of bias in general.

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta- analysis 2020 flow diagram of the study retrieval process

Overall, 23 studies evaluating the magnitude of non-adherence were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The number of participants involved in this study was 8,297 individuals with different mental disorders. Of those, 4,554 (57.18%) were schizophrenic, 1,524, and 847 were patients with MDD and BD, respectively. Among them, 3,388 participants were female in gender. Except for the study by Teferra et al. [48], which was a qualitative cohort study, all other studies were hospital-based cross-sectional quantitative in nature.

Subjective rating of medication adherence, such as self-reported measures of adherence, was the most commonly used type of measure. Thirteen studies utilize MMAS, 5 of them employed 4-item, whereas the rest 8 of them utilize 8-item MMAS. Among 13 studies using MMAS, non-adherence prevalence ranged from 32.60% [49] to 84.70% [18]. Five studies reported the prevalence of non-adherence assessed by the MARS method, with non-adherence ranging from 26% [17] to 51.2% [50]. Three studies used a self-reporting questionnaire technique developed after consulting relevant literature, with non-adherence ranging from 28.40% [51] in schizophrenics to 65.79% in shizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, MDD, BD, and AD [52]. Lastly, only one study employed objective pharmacy refill data, which is a compliant fill rate method, plus a subjective self-reporting method via a structured questionnaire patient interview [53] (Table 1).

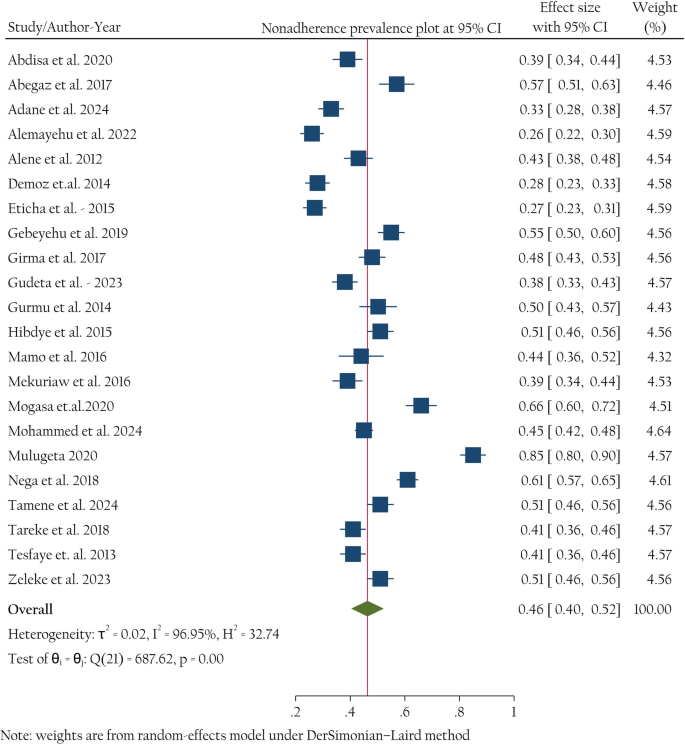

Twenty-two original studies participated in meta-analysis to compute the pooled proportion of psychotropic medication non-adherence among psychiatric patients. The pooled prevalence of medication non-adherence among psychiatric disorders was 46% (95% CI: 40%, 52%) (Fig. 2).

Forest plot for pooled prevalence of psychotropic medication non-adherence in psychiatric patients in Ethiopia. Box size corresponds with study weight (sample size). CI, Confidence Interval

The statistical test for heterogeneity revealed substantial variability among the studies, as indicated by Cochrane's Q statistic (χ2 = 683, p < 0.001). Additionally, the I2 statistic was 96.95% (p < 0.001), signifying a very high degree of inconsistency across the studies, suggesting that nearly all of the observed variation is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. The asymmetry of a forest plot provides visual insights into variability between studies (Fig. 2). In the Galbraith plot, there is a wide dispersion of point estimates away from the regression line, and some of them are even outside the shaded area, indicating high heterogeneity between estimates (Fig. 3).

Galbraith plot (n = 22). Box size corresponds with study weight (sample size). CI, Confidence Interval

To further investigate the source of heterogeneity subgroup analysis, univariate meta-regression analysis and leave-one-out sensitivity analysis were conducted.

Subgroup analysis

This analysis was conducted involving different moderators. The moderators employed to ascertain the source of significant heterogeneity in this review included the province where the studies were conducted, adherence measurement methods, types of psychiatric disorders, diagnosis modality of psychiatric disorders, sample size, JBI quality score, and the year of publication.

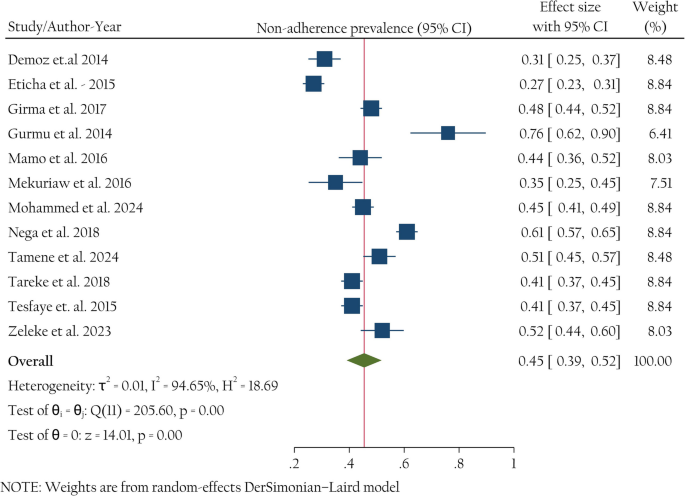

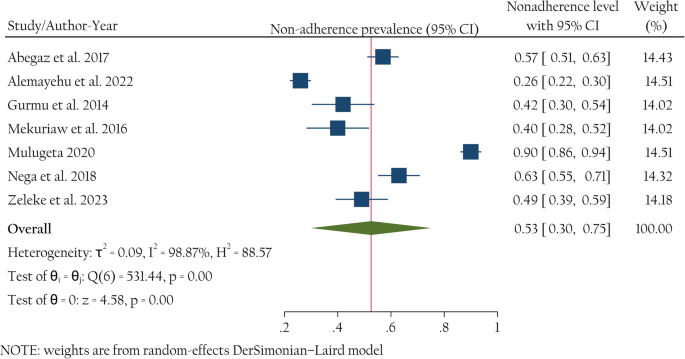

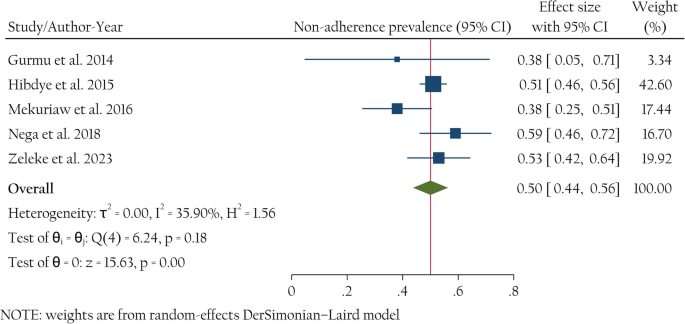

Subgroup analysis was conducted based on diagnosis type; severe mental disorders were considered due to the absence of segregated data on the other psychiatric disorders. The poor level of treatment maintenance among severe mental disorders (48%, 41%− 56%, I2 = 97.35%) is comparable to the pooled non-adherence level of general psychiatric patients (46%, 40%− 52%, I2 = 96.95). Non-adherence among patients with schizophrenia, MDD, and BD was 45% (39%− 52%, I2 = 94.65%), 53% (30%− 75%, I2 = 98.87), and 50% (44%− 56%, I2 = 35.9), respectively. A high level of heterogeneity persists in the two major severe mental disorders, schizophrenia and MDD (Figs. 4 and 5), while it is low in the case of the BD subgroup (Fig. 6).

Forest plot for pooled prevalence of non-adherence in schizophrenic patients in Ethiopia. Box size corresponds with study weight (sample size). CI, Confidence Interval

Forest plot for pooled prevalence of non-adherence in patients with MDD in Ethiopia. Box size corresponds with study weight (sample size). CI, Confidence Interval; MDD, Major Depressive Disorder

Graphic representation for pooled prevalence of non-adherence in patients with bipolar disorder in Ethiopia. Box size corresponds with study weight (sample size). CI, Confidence Interval

Subgroup analysis was conducted to assess variability between studies, considering some additional pertinent moderators. The second moderator next to disease type was adherence measurement methods such as MMAS- 4, MMAS- 8, MARS, and others (CFR and questionnaire methods). This adherence measurement scale difference might introduce heterogeneity between study estimates. The third moderator was the diagnosis modality of psychiatric disorders, which were DSM-IV and DSM-V guidelines. The difference in defining and diagnosing psychiatric disorders may cause heterogeneity. The next key moderator in our analysis is the year of study publication, specifically categorized as studies conducted before and after 2020. This cutoff point was chosen due to a significant healthcare reform in Ethiopia—by 2020, the country successfully expanded community-based health insurance to over 80% of districts. This reform aimed to increase access to affordable healthcare, including mental health services, which is likely to have influenced psychotropic medication treatment adherence rates [67]. Finally, sample size and the JBI quality score of the study may also be sources of heterogeneity.

As a result, heterogeneity in the prevalence of psychotropic treatment non-adherence among psychiatric patients across adherence measurement scales, diagnostic criteria, study quality, and study year of publication was insignificant, while the sample size (p = 0.03) and region where the study was conducted (p < 0.001) were found strongly significant. Therefore, sample size and study region might be part of the source of heterogeneity. A high level of heterogeneity still exists in all subgroups. The highest value of non-adherence level was observed among studies with small sample size (61%, 46%–76%, I2 = 96.61), while the lowest level was among studies involving medium sample size (39%, 33%–46%, I2 = 93.59). When we consider the pervasiveness of non-adherence from its measurement scale perspective, the highest prevalence of non-adherence was observed in MMAS- 8 (53%), and the lowest was in MARS (40%) (Table 2).

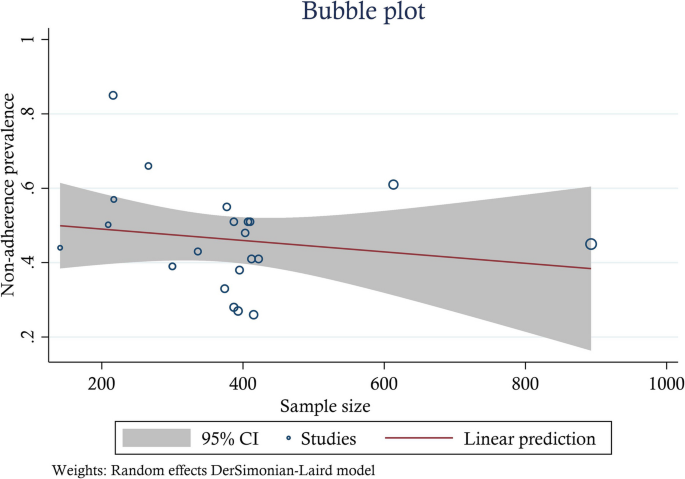

Meta-regression analysis

Univariate meta-regression analysis revealed that the sample size and region were statistically significant with psychotropic treatment non-adherence level among psychiatric patients. This suggests that the study sample size and province moderates heterogeneity to some extent, but are not themselves a sole source of heterogeneity. As the sample size increased by a unit, the likelihood of risk of non-adherence rate decreases by a factor of 0.22 (β = − 0.22, 95% CI: − 0.34 − − 0.09) and 0.15 times (β = − 0.15, 95% CI: − 0.28 − − 0.03) in medium and large size samples, respectively; with a total proportion of non-adherence explained by the covariate sample size by 37.03% (adjusted R2 = 37.03). The inverse linear relationship between sample size and non-adherence was visualized graphically (Fig. 7).

Graphical representation of the relationship between sample size and psychotropic medication treatment non-adherence among psychiatric patients in Ethiopia, 2024 (n = 22)

Besides, the pooled prevalence of non-adherence was higher in the Amhara region as compared to Tigray regional state of Ethiopia (β = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.02 − 0.49) (Table 3).

Sensitivity analysis

Leave-one-out analysis illustrating the subjective assessment of outliers. Each point estimate in this analysis represents the pooled effect size in the absence of that corresponding individual study and its 95% confidence interval. The analysis result revealed that there is no single study that affected the pooled estimate, as the overall estimate (0.46) is included within the confidence interval of all included studies (S1 Table).

Publication bias

Small study effect was assessed through subjective examination of the funnel plot of standard error of non-adherence prevalence by its logit of non-adherence status and Egger’s and Begg’s regression test. Funnel plot illustrates absence of publication bias due to its symmetrical nature (S1 Fig). The observed beta1 value of 3.47, with a standard error (SE) of beta1 = 6.04, yielded a z-statistic of 0.58, resulting in a probability (Prob >|z|) of 0.57. This statistically insignificant result in Egger’s test suggests the absence of publication bias. Furthermore, Begg’s test, examining small-study effects through Kendall’s score, revealed a score of 53.00 with a standard error of 34.89. The associated z-statistic of 1.49 and a probability (Prob >|z|) of 0.14 suggest no significant evidence of small-study effects according to Begg’s test. These statistical test results supplemented the potential symmetry in the distribution of effect sizes in the funnel plot.

All involved studies (n = 22) reported at least one influencing factor on psychotropic treatment adherence, except one study [54] (Table 4). Thirty influencing factors were extracted and then categorized into eight groups: sociodemographic factors, patient-related factors, lack of insight-related factors, self-stigma-related factors, negative attitude towards treatment factors, drug-related factors, substance use behaviour, and social support status. Despite the fact that grouping.

different factors into one category may introduce heterogeneity, we made a deliberate and prudent decision to pool them in order to accurately assess the overall association of these potential risk factors with non-adherence (Table 4). The presence of publication bias was checked via funnel plots, Begg’s test and regression-based Egger’s test under a random-effects model employing DerSimonian–Laird method (Table 5). Finally, stability of point estimate was assessed via leave-one-out sensitivity analysis.

Sociodemographic factors

Factors such as hospital distance taking ≥ 2 h, being unemployed, poor quality of life, illiteracy, older adults, being single, and rural living status were found to be predictors of non-adherence [17, 18, 23, 49, 55,56,57, 60, 64]. The results of the meta-analysis revealed that psychiatric patients who were characterized by those sociodemographic-related factors were 1.58 times at a higher risk of developing non-adherence to their psychotropic treatment after controlling patient-related factors, lack of insight related factors, negative attitude on psychotropic treatment related factors, social support status related factors, self-stigma, substance abuse, and drug-related factors. High levels of heterogeneity were noted, and the stability of the overall estimate was confirmed by leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (S2 Table). Additionally, no small study effect was found.

Patient-related factors

Six data sets that were concerned with the chronic nature of the disease, comorbidity, and regularity of follow-ups were collected from participant studies. Meta-analysis showed that patient-related factors. meaning that disease duration greater than 2 years, comorbid psychiatric illnesses, and irregular follow-up history were predictive factors for psychotropic medication non-adherence [55, 58, 65, 66, 68]. Low levels of heterogeneity were noted, and the stability of the overall estimate was confirmed by leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (S3 Table). Furthermore, no small study effect was found.

Lack of insight

Six levels of insight about the illness and treatment data sets, such as perceived spiritual causation, employing religious treatment options, and poor/no insights were collected from five studies [16, 23, 49, 57, 62]. Psychiatric patients who have poor insight about their illness and treatment carry 1.24 times higher risk of being non-adherent to psychotropic therapy due to lack of awareness or understanding of one's illness and the need for treatment. Moderate levels of heterogeneity were noted, and the stability of the overall estimate was confirmed by leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (S4 Table). Furthermore, no small study effect was found.

Negative attitude towards treatment

Effect of negative attitude on psychotropic treatment non-adherence is analyzed involving five studies [16, 58, 60, 63, 66] revealing a 1.28 times high risk of non-adherence in psychopharmacology as compared to those having a positive attitude toward their treatment. Neither small-study effect nor significant level of heterogeneity was identified. The stability of the overall estimate was confirmed by leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. (S5 Table).

Social support

Seven association data sets on social support status of psychiatric patients with psychotropic treatment non-adherence level were extracted and pooled by random effects meta-analysis [49, 57, 58, 60, 63, 65, 66]. This study revealed that no/poor social or family support was a risk factor for medication non-adherence by 1.39 times as compared to those having good social support. High levels of heterogeneity were noted, and the stability of the overall estimate was confirmed by leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (S6 Table). Furthermore, no small study effect was found.

Self-stigma

Meta-analysis on this association evaluation was done involving five studies [16, 17, 58, 60, 63]. Six data sets, such as moderate to high self-stigma and related suicidal attempts were collected. This analysis revealed that the perception or the feeling of psychiatric patients being stigmatized by their families, neighbors, health professionals, and other community members was a risk factor for psychotropic medication non-adherence by 1.57 times. Low levels of heterogeneity were noted, and the stability of the overall estimate was confirmed by leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (S7 Table). Furthermore, no small study effect was found.

Substance use

Eleven studies found the association of substance abuse risk behaviour with drug non-adherence among psychiatric patients [16, 23, 49, 50, 52, 56, 58, 60, 63, 64, 66]. Individuals who abuse substances, such as alcohol use, khat chewing, cannabis use, and cigarette smoking, were 16% less likely to be non-adherent than those who did not use substance [aOR = 0.84 95% CI: (0.71–0.97)]. High levels of heterogeneity were noted, and the stability of the overall estimate was confirmed by leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (S8 Table). Furthermore, no small study effect was found.

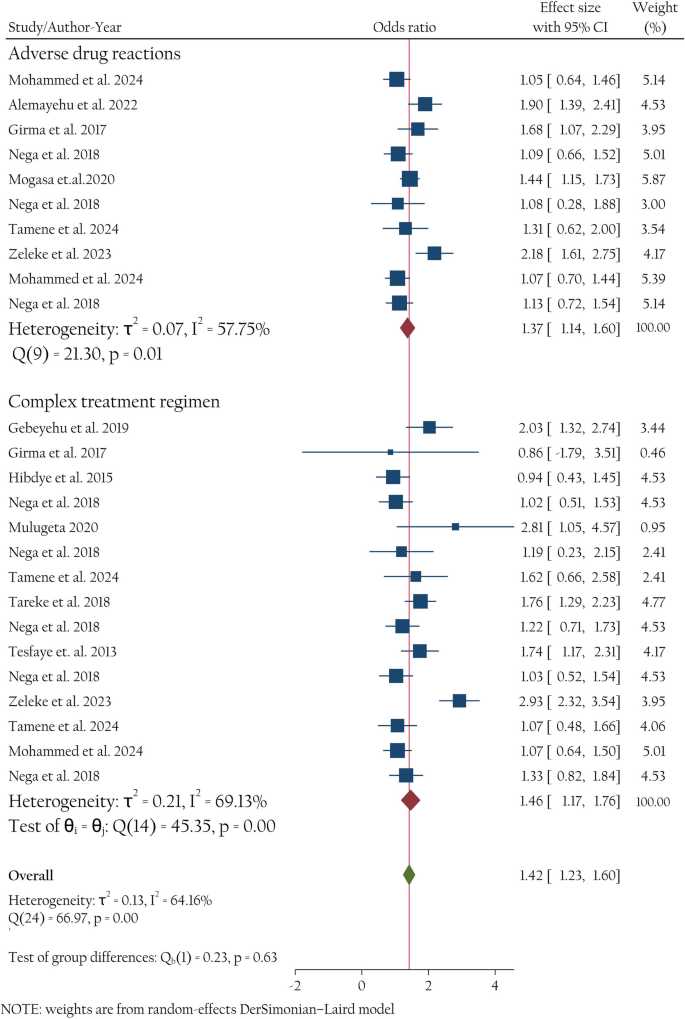

Drug-related factors

Twenty-six drug-related data sets were extracted from twelve studies [17, 18, 23, 50, 52, 57, 58, 60, 63,64,65,66]. Random effects model meta-analysis revealed that drug-related factors were pertinent factors associated with non-adherence [aOR = 1.42 (1.23–1.60) Regression-based Egger’s test under a random-effects model using the DerSimonian–Laird method revealed the absence of small-study effects (Prob >|z|= 0.21). whereas Begg's test showed the presence of small-study effects (Prob >|z|= 0.04). The funnel plot was symmetrical visually, which supplements Egger’s test (Table 6). The robustness of the meta-analysis results on the association between drug-related factors and non-adherence was further examined using the trim and fill approach. Following the incorporation of a single imputed unpublished study, the results indicated that the point estimation and 95% confidence interval of the aggregated effect sizes remained largely unchanged pre- and post-imputation (prior to clipping: OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.20–1.73; subsequent to clipping: OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.15–1.67). The results indicate that the meta-analytic results are reliable and less likely affected by potential publication bias. We have categorized these characteristics into adverse drug-related and difficult treatment-related subgroups. Moderate levels of heterogeneity were noted, and the stability of the overall estimate was confirmed by leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (S9 Table). Furthermore, small study effect was found.

Use of low-potency typical antipsychotics with antidepressants concomitantly, anticholinergic side effects, sleep-related side effect, extrapyramidal side effects were grouped in this category. Subgroup analysis revealed that ADRs were pertinent risk factors for non-adherence in psychiatric patients [I2 = 57.75%, pooled aOR = 1.37 (1.14 − 1.60)] (Fig. 8).

Forest plot of association of drug-related factors with psychotropic treatment non-adherence among psychiatric patients in Ethiopia

Many risk factors have been classified under this category, such as pill burden, polytherapy with antipsychotic medications, and being on treatment for long durations, even for life. Frequent rate of administration of multiple drugs for long treatment periods, even for life, were significantly associated with non-adherence [I2 = 69.13%, pooled aOR = 1.46 (1.17 − 1.76). Figure 8 displays the forest plot, which depicts the effect sizes of individual studies alongside the overall summary estimate.

Despite medication regimen adherence monitoring having been practiced since the time of Hippocrates, treatment non-adherence continues to be a global concern hitherto [69]. Particularly in developing nations, non-adherence to psychotropic treatment remains a pressing healthcare issue. It is a strong predictor of treatment failure in the psychiatric clinic continuum of care [70]. However, there is a dearth of concrete and contemporary evidence regarding its prevalence and influencing factors in a resource-limited setting.

In this study, pooled psychotropic medication non-adherence was 46%. This outcome was in line with studies conducted in France 30% [71], India 43%, 44% [72, 73], Singapore 34.5% [74], South Korea 50% [75], Iraq 38.1% [76], USA 55.1% for schizophrenics, and 37.3% for those with bipolar disorder [77], China (45.9%) [78], Qatar 37.6% [79], and Saudi Arabia 39.80% [80]. Furthermore, this result was in line with a meta-analysis studies: 49% [81], 42% [82], 40% [83] and 42% [84].

But this finding was lower than a study conducted in Nigeria 55.7% [85], USA 60% and 74% [21, 86], Montpellier, France 71% [87] and Nepal 89.4% [88]. Variation in study design, study settings, population, and measurement and definitions of non-adherence observed between studies may be the source of this discrepancy.

Medication non-adherence among patients with schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder was 45% (I2 = 94.65%), 53% (I2 = 98.87), and 50% (I2 = 35.9), respectively. The present finding might be in line with a study in India where psychotic disorders, BD, and MDD were 37%, 47%, 70%, respectively [73], and a study by Semahegn et al. [81], where medication non-adherence among patients with schizophrenia, MDD, and BD were 56%, 50%, and 44%, respectively. Furthermore, this study was in line with other studies revealing a non-adherence rate of 61%, 57%, and 52% in patients with schizophrenia, BD, and depression [89, 90].

Medication adherence is a dynamic process, which can be influenced by many risk factors [32]. Examining factors influencing adherence is key for physicians and researchers; recognizing certain risk factors facilitates tailored therapies for patients. Sociodemographic factors, patient-related factors, lack of insight, negative attitude towards the treatment, no/poor social support, self-stigma, and drug-related factors emerged as risk factors of non-adherence, although with residual heterogeneity.

Sociodemographic factors such as poor healthcare coverage of the country, unemployment status, poor quality of life, illiteracy rate, older age group, single marital status, and rural domicile level were pooled and revealed that they carry a risk of 1.58 times of developing non-adherence to their psychotropic treatment. This outcome was in line with a meta-analysis by J. Guo and his colleagues where sociodemographic factor were a risk factors for non-adherence (OR: 1.21) [91]. Furthermore, in line with the present study finding a single study in china revealed that being older is a risk factor for non-adherence (OR: 1.01) [78]. Poor socioeconomic status in a resource limited life trajectories like Ethiopia causes not only non-adherence to treatment but also can deliver mental illness [92]. Unlike to the present study, educational status was not a risk factor for non-adherence to anti-depressant medications (OR: 1.67, 95% CI: 0.43–6.44, p = 0.46) [93], being unemployed protects from non-adherence (OR = 0.41) [78], older age protects adherence (OR 1.02, 95% CI: 1.011–1.024, p < 0.0001) [94]. This discrepancy might be due to the reliance of many studies on self-reported methods for assessing non-adherence rather than objective measures.

Individuals with mental health problems are commonly subject to stigma, discrimination and victimization and are generally vulnerable groups. In this meta-analysis, self-stigma was found a significant risk factor for non-adherence, presumably increasing the likelihood of non-adherence by double. This underscores the critical role that psychological and social factors play a role in healthcare. Despite a universal problem, stigma and discrimination on people with mental illnesses is too high in developing countries. In a resource limited set up, the scarcity of mental health resources, coupled with cultural stigma, might complicate patients'adherence to treatments, especially for mental disorders [54, 95,96,97,98]. This study was in line with a study by P. Ghosh and his colleagues [99].

Patient-related factors such as the chronic nature of the disease, comorbidity, and irregularity of follow-ups, were predictive factors (OR = 1.47) for psychotropic medication non-adherence [55, 58, 65, 66, 68]. A study in Qatar showed that irregular attendance to clinic was a risk factor for non-adherence to medication [79] in line with the present study. In the contrary while polypharmacy and co-morbidity/multimorbidity were risk factors of non-adherence in this study, a study in Spain revealed that MDD/anxious patients being polymedicated and having another psychiatric diagnosis are protective factors against non-adherence [100]. This discrepancy may stem from healthcare system differences: in Ethiopia, limited resources and barriers to care can make managing multiple medications and co-morbidities challenging, thus reducing adherence. In contrast, Spain’s robust support systems may enhance adherence among polymedicated and co or multimorbidity patients. Furthermore, while not mentioned by the participant studies, affective temperaments were predictors of psychotropic treatment adherence [101, 102]. Among them hyperthymic temperament trait [101], was positively associated with higher treatment adherence, while irritable temperament [103, 104], cyclothymic temperament [101, 105, 106], and depressive temperaments were predictors of non adherence [101].

Lack of insight is another predictor variable of non-adherence, influencing it by a factor of 1.24. Psychiatric patients often lack insight into their illness or the necessity for therapy, a phenomenon prevalent in diseases such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and severe depression. They are confident in their ability to recuperate without pharmacological intervention. In some cases, cultural or personal views such as preferring natural remedies or believing in spiritual healing assuming the spiritual causation of disease leading patients to avoid pharmacological treatments in favor of alternative methods [49, 62, 107]. Not only patients, many health professionals believe that mental illnesses were not treatable [98]. This finding was in line with the other original [74, 85, 108] and systematic review studies [20, 109, 110].

Negative attitude towards treatment is another contributor to non-adherence. This problem typically develops because people have a skewed view of the efficacy of psychotropic medication in treating mental health issues. Some patients have concerns about long-term use of psychotropic medication as detrimental, could lead to dependency, a loss of autonomy, or even identity changes which contributes to a lack of enthusiasm toward the prescribed treatment regimen. This fear is rooted in a misunderstanding of how psychotropic medications work, especially regarding the distinction between therapeutic use and addiction. Skepticism toward medical advice is another symptom that people with these characteristics may experience. They may believe that their pharmaceutical prescriptions are driven more by financial gain than by their actual health needs. This outcome was in line with other systematic reviews [109, 110].

Poor social support was a risk factor for medication non-adherence by 1.39 times as compared to those having good social support. This outcome is in line with other studies where living alone (OR = 5.63) [74], low social support levels (O.R. = 1.528) [85], in addition systematic review conducted by Kalaman et [111] were predict non-adherence.

Drug-related factors like adverse reactions and complex regimens significantly predicted non-adherence (OR = 1.42) in this study, aligning with findings by Muhammad et al., where polypharmacy (OR = 1.87) and regimen complexity were linked to lower adherence rates [93, 110, 112]. Furthermore, adverse effects are consistently identified as risk factors for non-adherence in systematic reviews [79, 110, 113].

Whereas substance use behaviors were found a protective factor for adherence (aOR = 0.84 (0.71 − 0.97). This may be due to a legality of drugs like khat, tobacco, cigarettes, and alcohol in Ethiopia, openly sold at markets and chewed on the streets. Substance use is socially acceptable or normalized, reducing its perceived impact on daily functioning or treatment adherence. In such cases, individuals may not see their substance use as interfering with their mental or physical health treatment. Furthermore, in some cases, individuals using substances may still maintain strong social support networks, which can help encourage adherence to treatment despite substance use [20]. On the contrary there were systematic reviews revealing that substance abuse as a risk factor for treatment non-adherence [109, 110].

Our study benefited from a large sample size via involvement of all studies criticized in this systematic review and meta-analysis providing a better representation of the target population with psychiatric diseases in the study area. Except our study, to date no study globally has systematically analyzed the pooled point estimates of predictors of psychotropic treatment non-adherence. Subgroup analysis based on specific disease identity helps identify patient groups that might need tailored interventions.

Methodological obstacles difficulty to reliably measure whether a patient is taking medication or not due to the self-reported nature of adherence measuring scale used in many studies involved in this analysis. The definition of non-adherence varies depending on the strictness of the studies methodology. This may introduce bias to the meta-analysis. There was a high level of heterogeneity in the finding. We mainly used self-report adherence data liable for bias instead of a multi-method approach. Unable to perform subgroup analyses stratified by specific mental disorders further other than the severe mental disorders due to lack of segregated data in those group of patients to locate potential sources of heterogeneity. Similarly unable to conduct subgroup analysis based on the stringent nature of studies upon setting measuring cutoff points in defining non-adherence due to its varied nature.

Psychotropic treatment non-adherence among psychiatric patients was quite common in a resource-limited settings. Sociodemographic factors, patient-related factors, lack of insight, negative attitude to the treatment, no/poor social support, self-stigma, and drug-related factors emerged as risk factors of non-adherence. This comprehensive analysis can indeed be considered as a high-grade ore for policymakers despite our findings should be interpreted with caution owing to the substantial heterogeneity. Notwithstanding stringent methodology in this work, depending on cross-sectional studies constrain its clinical guidance. Future research ought to focus on larger, long-term prospective studies in clinical settings to offer more meaningful insights on predictors.

Clinicians should be alert about non-adherence, which jeopardizes treatment outcome. Adopt and implement straightforward, patient-centered, tailored and pragmatic interventional strategies on pertinent predictors are crucial due to the diverse nature of non-adherence drivers. This includes collaborative decision-making during prescriptions, pharmaceutical care interventions such as simplifying medication regimens, and education focused on adherence by rectifying myths and beliefs held by patients with scientific information and explanations. Furthermore, adherence will be improved if the government health agenda prioritizes mental health services, ensuring it community-based and integrated with the primary health care system. At last proactive prevention, recognition, and management of non-adherence in this population is warranted.

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

- DSM- 5-TR:

-

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, text revision

- BD:

-

Bipolar disorder

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- AD:

-

Anxiety disorder

- ADR:

-

Adverse drug reactions

We like to convey our appreciation to the authors of the studies featured in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

The authors possess no financial support for this review endeavor.

Not applicable.

Not Applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Zewdu, W.S., Dagnew, S.B., Tarekegn, G.Y. et al. Non-adherence level of pharmacotherapy and its predictors among mental disorders in a resource-limited life trajectories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 25, 512 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-025-06838-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-025-06838-9