BMC Nutrition volume 11, Article number: 120 (2025) Cite this article

Adolescence is a distinct stage of life characterized by significant physical, psychological, and cognitive development. Maintaining healthy eating behaviors during this period is crucial for preventing various forms of malnutrition and non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and cancer. This study aimed to assess the effects of educational interventions based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB) on improving the healthy eating intention of adolescents in selected schools in Bardiya District.

A quasi-experimental study was conducted among eighth and ninth graders aged between 12 and 18 years from two public schools in Badhaiyatal Rural Municipality of Nepal, one as an intervention (IG) and the other as a control group (CG), selected randomly. A total of 167 students participated in the study, with 82 in the IG and 85 in the CG. Data were collected through self-administered questionnaires at baseline and4 weeks after the intervention. The intervention package consisted of an interactive lecture, a group discussion, a poster, an educational video, and a song. In contrast, the control group followed the regular school curriculum without any additional nutrition education. The educational intervention for the IG consisted of 6 sessions, each lasting 60 min. Data were entered and analyzed in SPSS V22, using a chi-square test, paired t-test, and linear regression.

The educational intervention led to significant improvements in knowledge and TPB constructs, with these changes being statistically significant (p < 0.001). The adjusted mean score increases in TPB constructs because the interaction of time and intervention increased from 0.47 to 5.49. The highest gain (β = 5.49; p = 0.001) was observed in the perceived behavioural control score whereas, a minor improvement was seen in behaviour (β = 0.47; p = 0.112). After the intervention, a net increase in the healthy eating intention score was 14.8% compared with that of the control group.

The study concluded that multipronged educational intervention may be effective in improving adolescents’ healthy eating intentions, mainly through perceived eating control and attitude. Model-based and construct-oriented health education can be used with caution in schools to promote healthy eating intentions.

The ages of 10 to 19 years constitute adolescence [1], an opportune time for health-promoting behavior and chronic disease risk reduction interventions with the potential to influence lifestyle-related disorders in adulthood [2]. Adolescents aged 10–19 years transition to adult social values and roles [3]. During this period, their body shape changes [4], which represents approximately one-quarter of Nepal’s population [5]. This period, notably when an individual is transitioning from growing to developing behaviors into adulthood as one moves through childhood and reaches old age (aged 10–24 years), represents a window of opportunity for preventing ill health [6].

Environmental factors and lifestyle choices significantly contribute to the increasing rates of obesity and the subsequent development of major non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [7]. These NCDs frequently stem from habits established in youth [8, 9]. During adolescence, fast growth spurts increase the requirement for macro- and micronutrients throughout adolescence [10]. Malnutrition may develop later in life if these nutritional requirements are not satisfied. Maintaining a robust immune system requires a healthy lifestyle, which includes eating a balanced diet and engaging in regular physical activity [11]. Adolescents generally lack awareness about recommended diets and activities [12, 13].

A key contributing factor to the development of chronic non-communicable diseases is poor dietary behavior [14]. People must comprehend nutrition to encourage them to eat healthier products [15, 16]. Schools are ideal for implementing nutrition education programs because they can reach a large adolescent audience [17]. Children are estimated to consume a third of their total daily energy intake during school hours [18]. This makes school-based nutrition education programs effective in encouraging adolescents to develop healthy eating habits [19, 20]. Despite various efforts by governments and organizations to encourage healthy eating, research shows that adolescents, especially those in developing countries such as Nepal, often have poor nutritional knowledge and habits [21]. Evidence suggests that children in these regions consume more unhealthy foods due to a lack of information and misconceptions about healthy eating [22, 23]. The consumption of large amounts of junk food is associated with a dramatic decrease in healthy food intake. High income, rapid urbanization, free home deliveries, mouthwatering advertisements, and international cuisines have contributed to a rising trend in increased junk food intake [24, 25]. Many adolescents lack proper knowledge or get the wrong information about food, which harms their eating habits [26]. Bohara et al. and Saavedra et al. reported that 41.1% of teens eat fruits and veggies, whereas 63.3% reported that they had junk, and ready-made food in the past month [27, 28]. This has caused teens’ diets to become much worse, leading to poor nutrition and food-related health issues. Another study showed that after teens took part in a nutrition class, they ate better and made healthier choices. This changed their thoughts about food and what they ate [29].

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), introduced by Ajzen and Fishbein in 1980, is one of several models focused on understanding human behavior [30]. It stands out as an educational model centered on behavioral intention. According to TPB, the strongest predictor of behavior is an individual’s intention to act [31, 32]. This intention is shaped by three key factors: their attitude toward the behavior, and their perceived ability to carry out the behavior successfully. TPB helps change health habits in the context of nutrition education [33]. Interventions based on this theory were found more effective in increasing dietary intention and behaviour than other theories [32, 34, 35]. Various studies have shown that the Theory of Planned Behavior has been utilized to examine people’s eating intentions and behaviors and has been widely applied in nutritional intervention research [36,37,38,39,40]. This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of a multi-strategy educational intervention based on TPB in promoting healthy eating intentions among adolescents in Nepal.

This quasi-experimental study was conducted in two public schools in Badhaiyatal Rural Municipality of the Bardiya District in Nepal. The study was conducted from November 2023 to June 2024. The TREND (Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs) principles were followed in the documentation of the research findings and methodology [41].

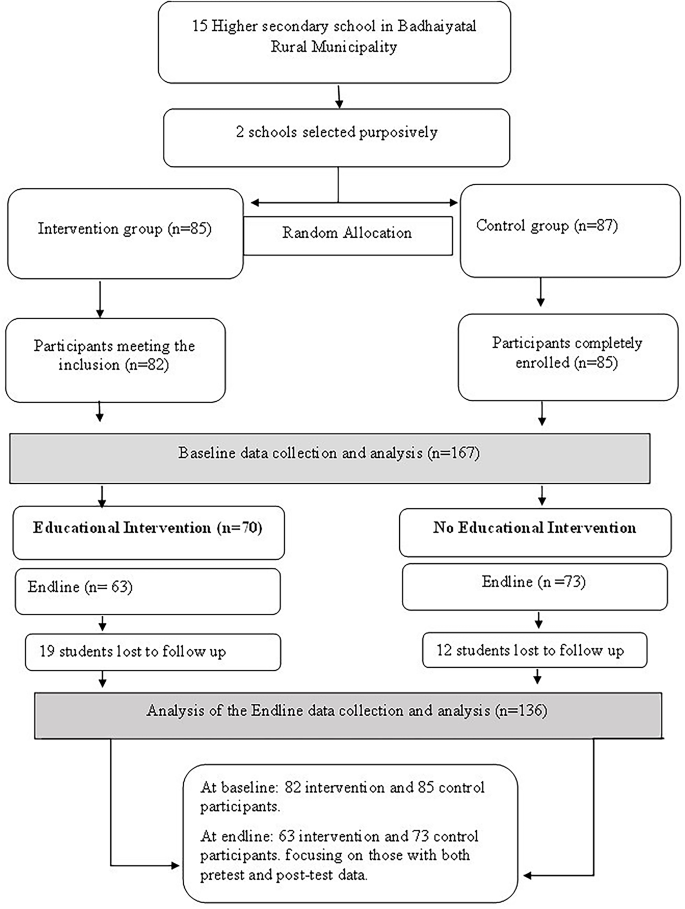

The participants were adolescent students aged 12 to 18 years, enrolled in grades eight and nine (Fig. 1). We enrolled the regular students of these grades, attended all educational intervention sessions, completed both baseline and endline questionnaires, and obtained assent from adolescent before securing parental consent, as all participants were minors under the age of 18 were included in this study Students were excluded if they had any medical conditions (physical or psychological disorders), were absent during any phase of the study.

A list of basic and secondary public schools was obtained from Badhaiyatal Rural Municipality. Out of 15 schools, only two were chosen purposefully because they had enough adolescent students to meet the required sample size and ensure that participants from both the control and intervention groups shared similar locality and characteristics.

To minimize contamination and maintain the integrity of the study, schools for control and intervention groups were selected from separate regions- one from the eastern and one from the western part of the Rural Municipality. The two selected schools were then randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group through a simple coin toss. With the help of the school’s administrative registry, a detailed list of classes was compiled for each school. As a result, the intervention group consisted of 82 participants, whereas the control group consisted of 85 participants at baseline. Finally, after completing the post-intervention phase, 63 completed responses in the control group and 73 completed responses in the intervention group were obtained. Figure 1 shows the selection of study participants. Of these, 12 participants in the control group and 19 participants in the intervention group dropped out because they were absent during the intervention period and the end line.

During the intervention phase, the focus was on implementing a health education intervention aimed at promoting healthy eating behaviors. The intervention was given to the intervention group, but the control group did not receive any additional nutrition education beyond the regular curriculum provided by the school.

Trained nutritionists and researchers provided one hour of nutrition education session a day per week for the intervention group through interactive lectures with “question-answer sessions”, group discussions, posters, educational videos, songs, and PowerPoints for the intervention group in each grade (grades VIII and IX). As a result, separate nutrition education sessions were given to the students in each grade. The education package was developed by a researcher, and all the materials were reviewed by experts. Face validity was ensured through feedback from external reviewers, while content validity was established through expert consultation and a literature review. Reliability was confirmed through pretesting, where the package was administered to a sample group to evaluate its consistency and effectiveness.

The education package was developed, and all the materials were reviewed by experts. Face validity was established by gathering feedback from external reviewers, while content validity was confirmed through expert consultation, a literature review, and pretesting to ensure the materials effectively conveyed the topics to the target audience. Reliability was ensured through pretesting, where the package was administered to a sample group to assess its consistency and effectiveness.

Classes were made interactive by carrying out two-way question-and-answer sessions after the completion of each topic. To maintain participant attention, all teaching materials were developed in a pictorial format whenever possible and culturally and language-appropriate manner. Additionally, educational videos and songs were used for edutainment purposes to promote healthy eating behaviors. The participants were involved in teamwork, where they wrote lessons learned on chart paper and presented them at the end of each session, enhancing interactivity in the classroom. However, the education package was not given to the control group. At the end of each session, all the materials used for the intervention were printed and given to all the participants (refer to Table 1 and supplementary materials).

The sample size was calculated using a formula for comparison between two paired groups in the Open-Epi software [42]. A power of 80% and a 95% confidence level were assumed for the analysis. The calculation also incorporated a design effect of 1.5 and accounted for an anticipated attrition rate of 10%. Based on a school-based intervention study conducted by [43], the standard deviation of attitudes toward a healthy diet in the pre-intervention group was 27.15, and in the post-intervention group it was 18.03. The average mean difference observed was 15.67.

The formula used for calculating the required sample size 𝑛=((𝑧1−𝛼/2+𝑧1−𝛽) × (SD12 + SD22)/ (M1- m2)2.

Thus, the minimum sample size required in each group was 60. We adopted a census approach at the classroom level; all students in the selected classes (i.e., 8 and 9) were included in the study to yield a sample size of 167 at baseline.

Using semi-structured, pre-tested questionnaires, the researcher collected data through face-to-face interviews. The baseline interviews were conducted at both schools and lasted approximately thirty minutes each. Endline data were gathered following the 4-week nutritional education intervention.

The questionnaires were developed in English, translated into Nepali, and then back-translated into English to ensure linguistic and contextual accuracy. Pretesting was conducted among 30 students from grades 8 and 9 in a non-study school from Badhaiyataal Rural Municipality, demographically similar to the target population. Insights from this pilot helped refine the tools for better clarity and feasibility.

The tools were developed by reviewing literature and existing validated questionnaires, and they were based on the key constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). A panel of experts including two public health professionals, one dietitian, one nutritionist, and one health education specialist provided input to ensure content validity, following TPB-specific questionnaire design guidelines.

To assess content validity, the Lawshe method was employed. Items with a content validity ratio (CVR) above 0.6 were retained. Feedback from experts and pretesting led to several revisions for cultural relevance and clarity. cultural relevance and clarity. The internal consistency of the TPB constructs measured using Likert scales was evaluated through Cronbach’s alpha. calculating Cronbach’s alpha, resulting in values of 0.82 for attitude, 0.86 for perceived behavioral control, and 0.88 for intention. These values indicate strong reliability of the scales.

The questionnaire was revised appropriately based on pretesting, with adjustments made based on the findings and expert feedback. Attitude (r = 0.68) and perceived behavioral control (r = 0.57) showed moderate positive correlations with intention and were retained for further analysis. In contrast, subjective norms (r = − 0.044) showed a weak negative correlation and were excluded from further analysis. These findings align with previous studies, suggesting subjective norms are weak predictors of intention [44, 45]. Based on pre-test insights, necessary modifications were made to research tools for better feasibility and clarity.

The socio-demographic data gathered included age, sex, class level (grade), religion, ethnic group, parents’ educational background, and occupation. Nutritional knowledge was assessed using ten factual questions, scored as 1 for correct and 0 for incorrect answers. Healthy eating behaviors were measured via seven questions, participants who reported practicing healthy eating behaviors received one point per question, and those who did not practice healthy eating received zero points.

Attitude, PBC, and intention were each measured using eight items on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree), with total scores ranging from 8 to 56 for each construct.

Healthy eating behaviors were measured via seven questions. Participants who reported practicing healthy eating behaviors received one point per question, and those who did not practice healthy eating received zero points.

For the BMI assessment, trained field researchers measured the weight and height of participants at their schools. Weight was recorded once digital scales were placed on a flat surface, with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes. Height was measured once a standard clinical height measurement scale was used, with participants standing barefoot. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) / height (m²).

The data were entered into EpiData V3.1 and then transferred to the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) V22.0 for analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of the variables. The data followed a normal distribution (p’s lowest-highest of the variables); therefore, parametric tests were applied.

Socio-demographic factors were compared between the intervention and control groups at baseline. A paired t-test was used to compare the baseline and end-line characteristics of the variables within each group. Additionally, an independent t-test was used to evaluate the changes in nutrition knowledge, TPB scores, and behavior scores between the two groups at both baseline and end-line.

Comparing the changes in scores between the intervention group, which considers both time and intervention effects, and the control group, which considers only the time impact, allowed for the calculation of the unadjusted difference-in-differences (DiD). Regression modeling was performed with the equation Y = β0 + β1 * [time] + β2 * [intervention] + β3 * [time * intervention] + \(\:\in\:\). This equation was used to obtain the adjusted interaction between time and intervention. In this formula, the difference-in-differences (DiD) is indicated by β3, and Y represents the overall mean score [46]. For statistical significance, a p-value of less than 0.05 was used.

This study included a total of 167 participants: 82 in the intervention group and 85 in the control group at baseline. The mean age of the participants was 14.10 years in the intervention group and 14.32 years in the control group. There were more female participants than male participants in both the intervention and control groups. Most of the participants identified as Hindu or Brahmin/Chhetri in both groups. A significant proportion of mothers in both groups were engaged in agriculture, while fathers had agriculture as their major occupation in the intervention group and foreign employment as their major occupation in the control group.

In the comparison of the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants in both the intervention and control groups, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were found between groups in any of the socio-demographic characteristics except the fathers’ employment status. Thus, this statistically ensures homogeneity among the participants in the intervention and control groups (refer to Table 2).

The mean follow-up scores for all TPB constructs, including knowledge, increased among the intervention group. In contrast, the scores slightly decreased among the control group in all the TPB constructs except knowledge and BMI. The unadjusted DiD mean scores ranged from − 1.8 to 5.49 points, increasing by -8.26–20.49%. The highest unadjusted DiD was observed for the knowledge score (20.49%). The unadjusted DiD point score for the intention was 5.19, representing a 14.88% increase from the baseline score in the intervention group (Table 3).

The adjusted increase in the mean score due to the interaction of time and intervention increased from 0.47 to 5.49. The highest gain (beta = 5.49) was seen in the perceived behavioural control score, whereas a minor improvement was observed in behaviours (beta = 0.47) (Table 4).

The present study demonstrated that the educational intervention was effective in improved adolescents’ nutrition related knowledge, attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and intentions, based on TPB. Nutrition education is essential for encouraging healthy eating and any strategies focused on changing behavior. School-based nutrition education, particularly when introduced early, is essential for promoting healthy eating behaviors [47]. TPB has been used as a theoretical framework in many studies on healthy diets and is effective in increasing healthy eating intentions among adolescents [32, 43, 48, 49]. A systematic review by Hardman et al. [50] of the theory of planned behavior in behavior change interventions was conducted by Hardman et al. [50] found that 50% of TPB-based interventions improved intentions and 67% influenced behavior.

In the present study, the intervention group showed significant mean score improvements from baseline to endline in knowledge (20.49), attitudes (12.49), PBC (16.16), and intentions (14.88), while the control group showed minimal or negative changes in these constructs. All improvements within the intervention group were statistically significant, except for BMI, likely due to the short duration of the study and its focus on raising awareness and promoting healthy nutritional practices rather than inducing biological changes.

The changes observed in the control group might be due to the passage of time, whereas the improvement in the intervention group likely resulted from both the time effect and the intervention itself. Analyzing the mean score difference, the intervention group showed positive changes across all TPB constructs. In contrast, the control group showed a slight negative difference in all the constructs except for the knowledge. A similar pattern was reported by Gharlipour et al. in a study on breakfast habits among sixth-grade students [51]. A study by Dhauvadel et al. used an extended TPB, which also included intention toward a healthy diet, added to a one-and-a-half-hour session delivered over two consecutive days among grade nine students via similar methods, and performed a follow-up for 15 days. The results also revealed significant improvements (p < 0.001) in all measured TPB constructs except subjective norms, where there was no significant change in the control group [49].

Another study using five 40-minute TPB-based sessions also reported improvements in all constructs except subjective norms [51], which our study did not measure. Our follow-up period was four weeks, shorter than other studies with two-month or longer follow-ups, but still showed meaningful short-term behavior changes and increased intentions. Among all constructs, knowledge improved the most, with a gain exceeding 20%. As knowledge serves as the foundation for changing other TPB components [52] This aligns with a systematic review showing a 13% increase in nutrition knowledge post-intervention [53]. Additionally, since the participants were students, they might have been exposed to other sources of information during the study period, which was beyond the researchers’ control.

This study revealed that the intervention significantly improved attitudes toward healthy eating, possibly because students perceived greater benefits than barriers to healthy behaviors. These findings support previous TPB-based studies among students [51, 54,55,56,57,58].

In another study among students with dietary behavior in India, intervention with 2 sessions of 1 h each per class resulted in significantly increased attitude scores at 15 days (paired t-test I=-15.51, p < 0.01, C = 1.517, p = 0.131) [59]. In contrast, another TPB-based study found no significant changes in attitudes, PBC, or intentions after three months. This could be explained by several factors, including the lack of a direct intervention based on this construct, the duration of the intervention, and the research methodology [43]. Moreover, other studies reported significant improvements in PBC and intentions (p < 0.001) [60]. Another study showed that the attitude and intention construct of the TPB were more remarkable than the changes in the different constructs (p < 0.001) [49].

In the present study, there was no significant difference in BMI after the intervention among the groups. These results align with those of another study [61]. This could be due to the short-term nature of the intervention and the intervention package’s focus on awareness and the promotion of healthy nutritional practices rather than behavioral changes.

In the present study, compared with the control group, the intervention group had significantly greater intentions for healthy eating (p < 0.001). Notably, similar findings were reported in studies by [56, 62, 63], where intervention groups showed significantly higher intention scores for healthy eating compared to the control group (p < 0.001). Similarly, Tsorbatzoudis reported that a TPB-based intervention, including posters and lectures promoting healthy eating, led to more positive intentions in the treatment group compared to the control group (p < 0.001) [60].

One of the strengths of the study is assessing the eating intention-behavior gap using the TPB as a framework, which is generally used for healthy diet intention only. Another strength is the multi-strategy educational approach, which was relatively simple, short-term, and contextualized in the study settings, thus making it feasible to implement. Third, this study used a quasi-experimental design with DID analysis, controlling for extraneous factors, and more contextualizing the intention-behavior gap.

The study have also some limitations though. Firstly, purposively selected schools may have introduced selection bias to some extent although efforts were directed to minimize it. Then, a dropout rate of nearly 19% may have led to some attrition bias. Also, the study might have involved response bias since the data were self-reportedly collected. The quasi-experimental design lacked a longitudinal approach, which restricted the ability to measure long-term BMI changes and recommendations should be left for future long-term studies. This study excluded subjective norms due to low pretest correlation and limited predictive value; future studies should incorporate more context-specific and socially tailored intervention components to better capture their influence.

The study concluded that multi-strategic educational intervention is effective in improving healthy eating related knowledge, attitude, perceived behavioral control, and intentions but do not significantly impact the healthy eating behaviors among school-aged adolescents. Further research is warranted to enhance intention-behavior compatibility and stronger designs.

Data will be provided upon reasonable request.

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- IRC:

-

Institutional review committee

- NCDs:

-

Noncommunicable diseases

- SHNP:

-

School health nutrition program

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for the social sciences

- TPB:

-

Theory of planned behavior

- TREND:

-

Transparent reporting of evaluations with nonrandomized designs

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants who generously contributed their time, responses, and involvement in this study. Our heartfelt thanks also go to the teachers and students of the respective schools for their invaluable support and cooperation throughout the research.

This research was conducted without any specific financial support from funding agencies.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee (IRC) of Pokhara University (Reference no. 128) by the Declaration of Helsinki. Formal permission was secured from the respective public schools. Written informed assent from participants and consent from their parents or guardians was obtained. The data collector explained the study’s objectives to each participant before gathering baseline data and delivering the nutrition education intervention. The participants and their parents or legal guardians were informed about the voluntary nature of participation, their right to withdraw at any time, and the confidentiality of their identities.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Bhandari, P., Adhikari, S., Bhandari, P. et al. Multi-strategy instructional intervention for healthy eating intention among school going adolescents: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Nutr 11, 120 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-025-01105-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-025-01105-2