As US President Donald Trump does his worst to hobble China’s economy, China’s President Xi Jinping may be beating him to the punch.

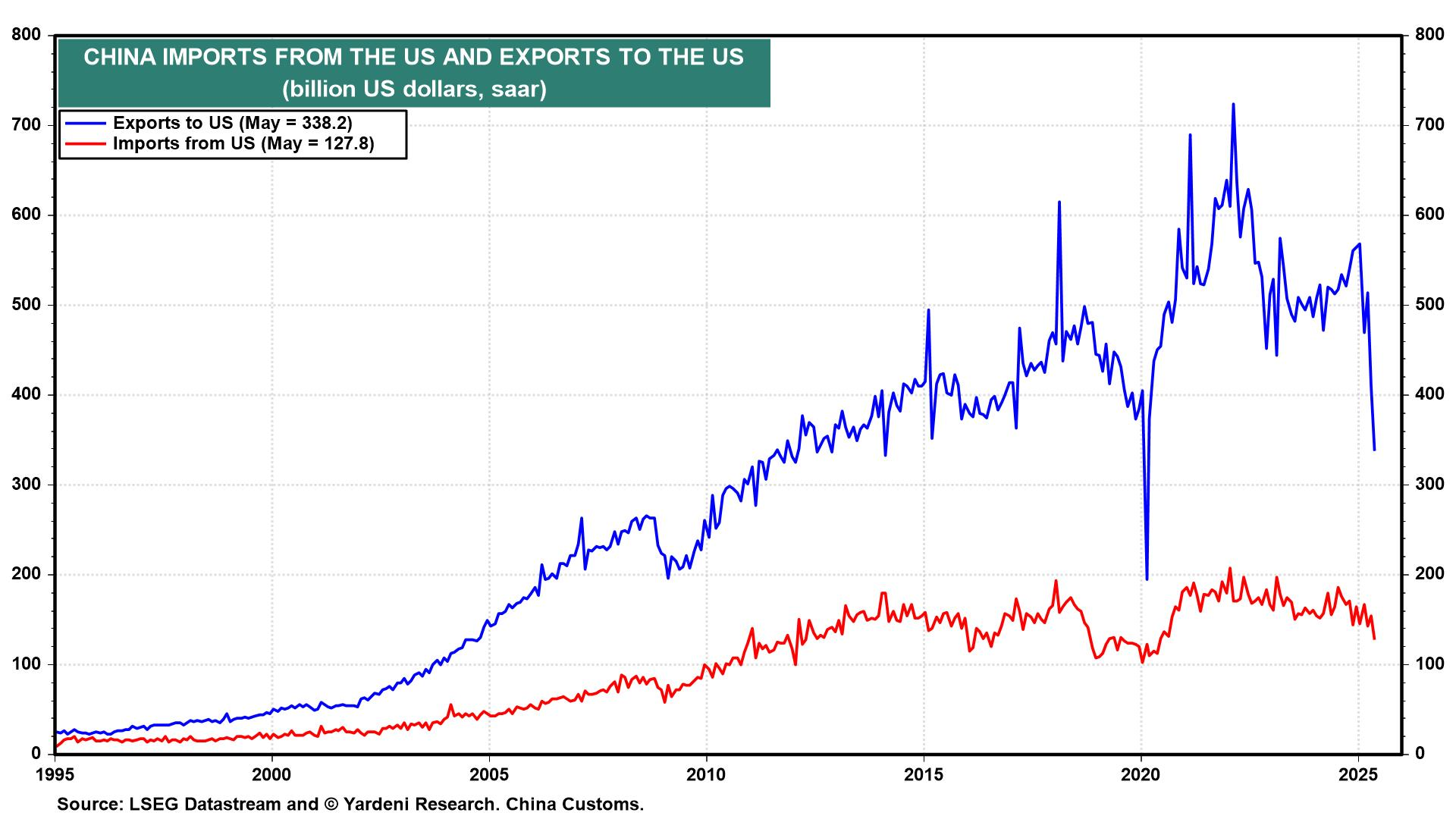

There’s no doubt that Trump’s tariffs are destabilizing Asia’s biggest economy. Though the current 30% US tariff on Chinese imports is a fraction of Trump’s earlier 145% China tax, it’s still prohibitively high—Smoot-Hawley Act high. It’s complicating President Xi’s ability to stimulate China’s hamstrung economy sufficiently to make this year’s 5% real GDP growth target.

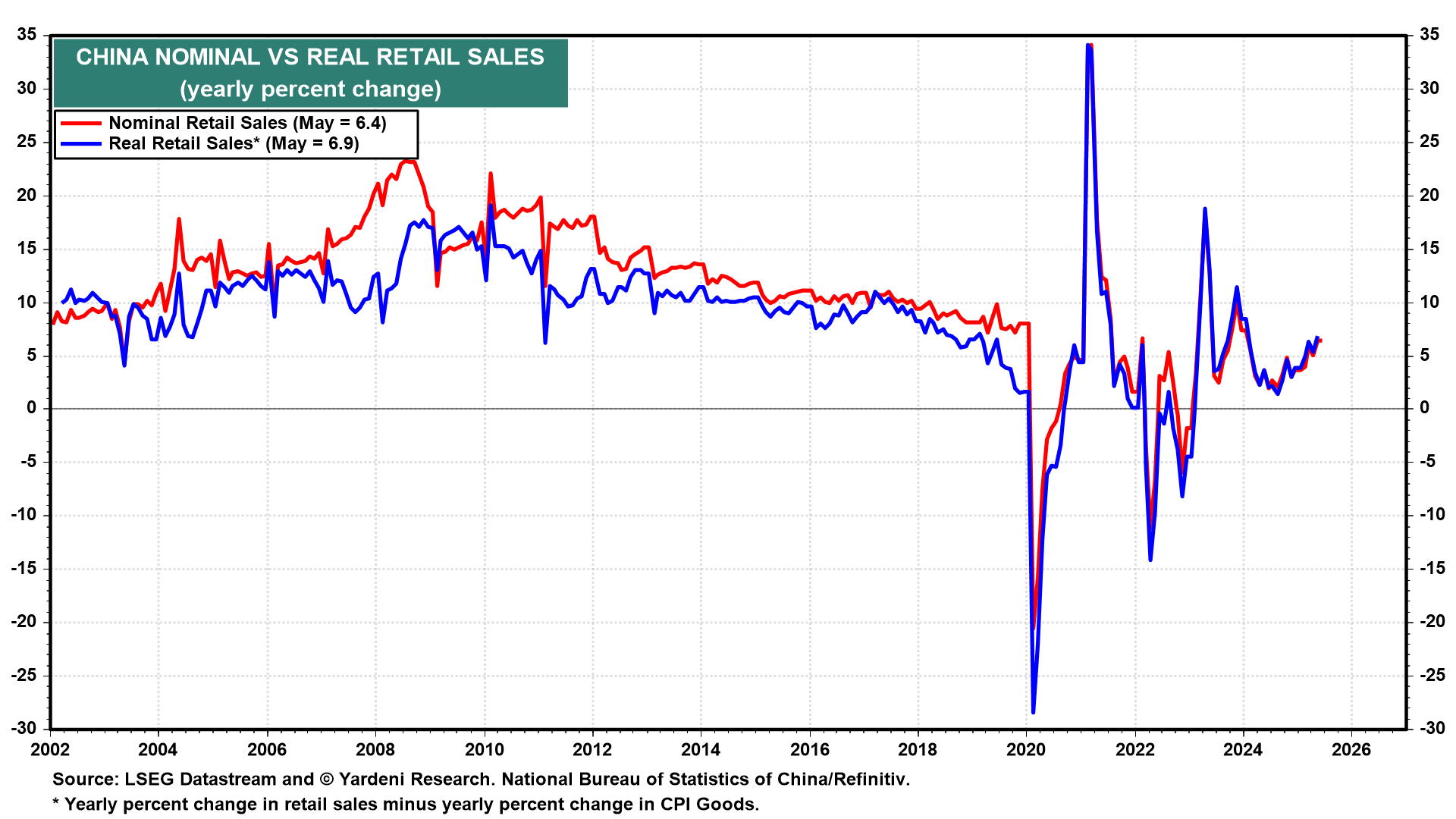

Ironically, among the biggest wounds limiting China’s growth potential is a Xi-inflicted one: The troubling chronic weakness of consumer spending, which shows no signs of picking up sustainably. Chinese consumers prioritize saving, to the detriment of spending, owing to the absence of a social security safety net. Xi has struggled to reverse this trend, but could be doing more to incentivize spending.

There are, of course, months when Chinese state media will jump on a particular economic statistic as a harbinger of a consumption boom to come. Case in point: the 6.4% y/y rise in in May, the biggest since December 2023. Yet China has produced such short-term blips many times before.

The latest can be attributed to a mix of central bank easing, government trade-in programs and subsidies targeting home appliances and tech goods, and optimism over Trump’s tariff downshift.

However, such policies treat the symptoms of China’s troubles, not the underlying conditions, which are flaring up anew:

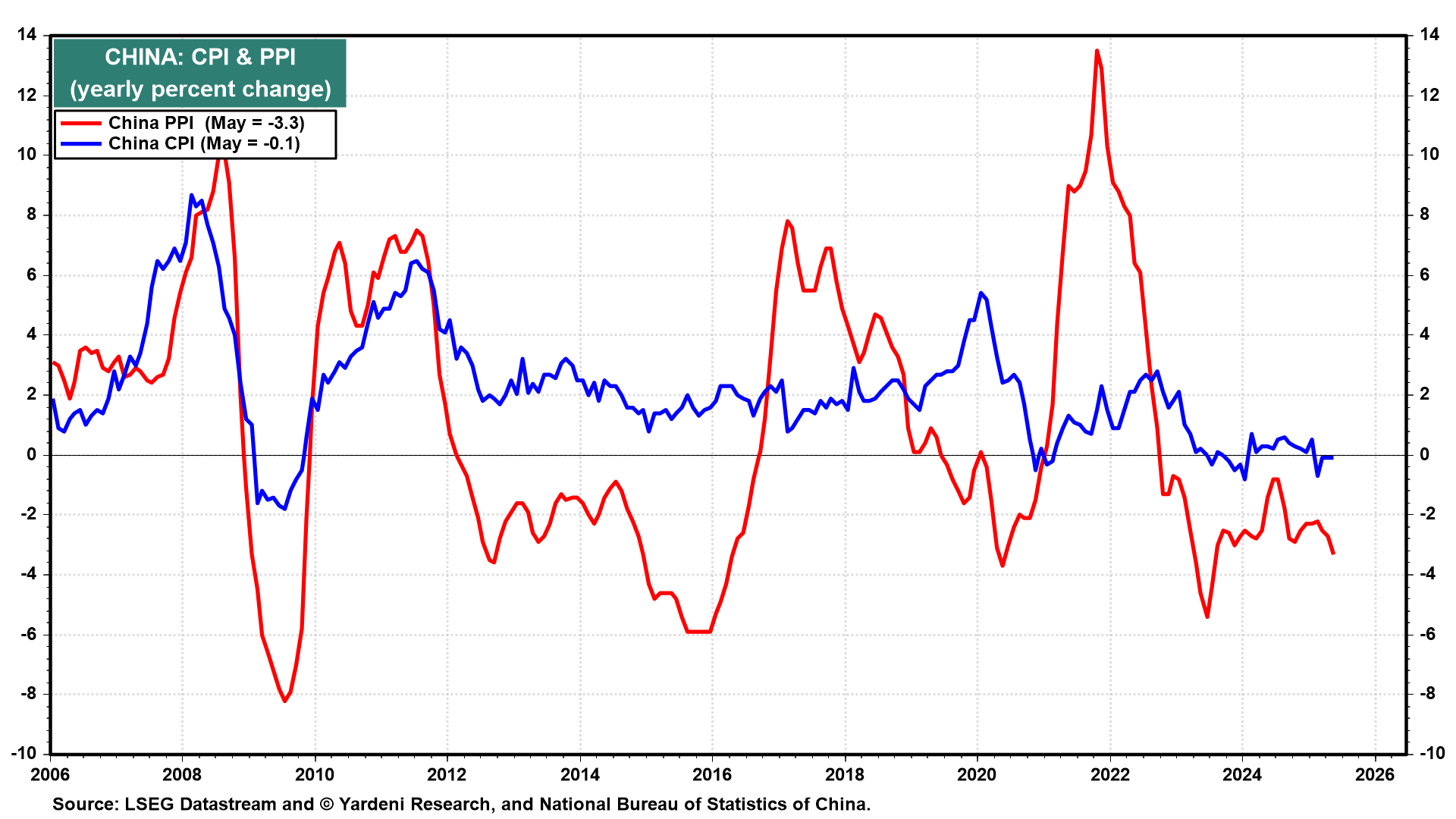

(1) Weak consumer confidence is fueling deflation. Consumer prices fell for a fourth straight month in May despite Beijing’s stimulus moves. In the latest month, China’s fell 0.1% y/y.

Price wars in the auto sector may be exacerbating the nation’s deflation trend going forward. Under the surface, meanwhile, this falling-price dynamic is thriving. fell 3.3% y/y in May, the largest drop since July 2023.

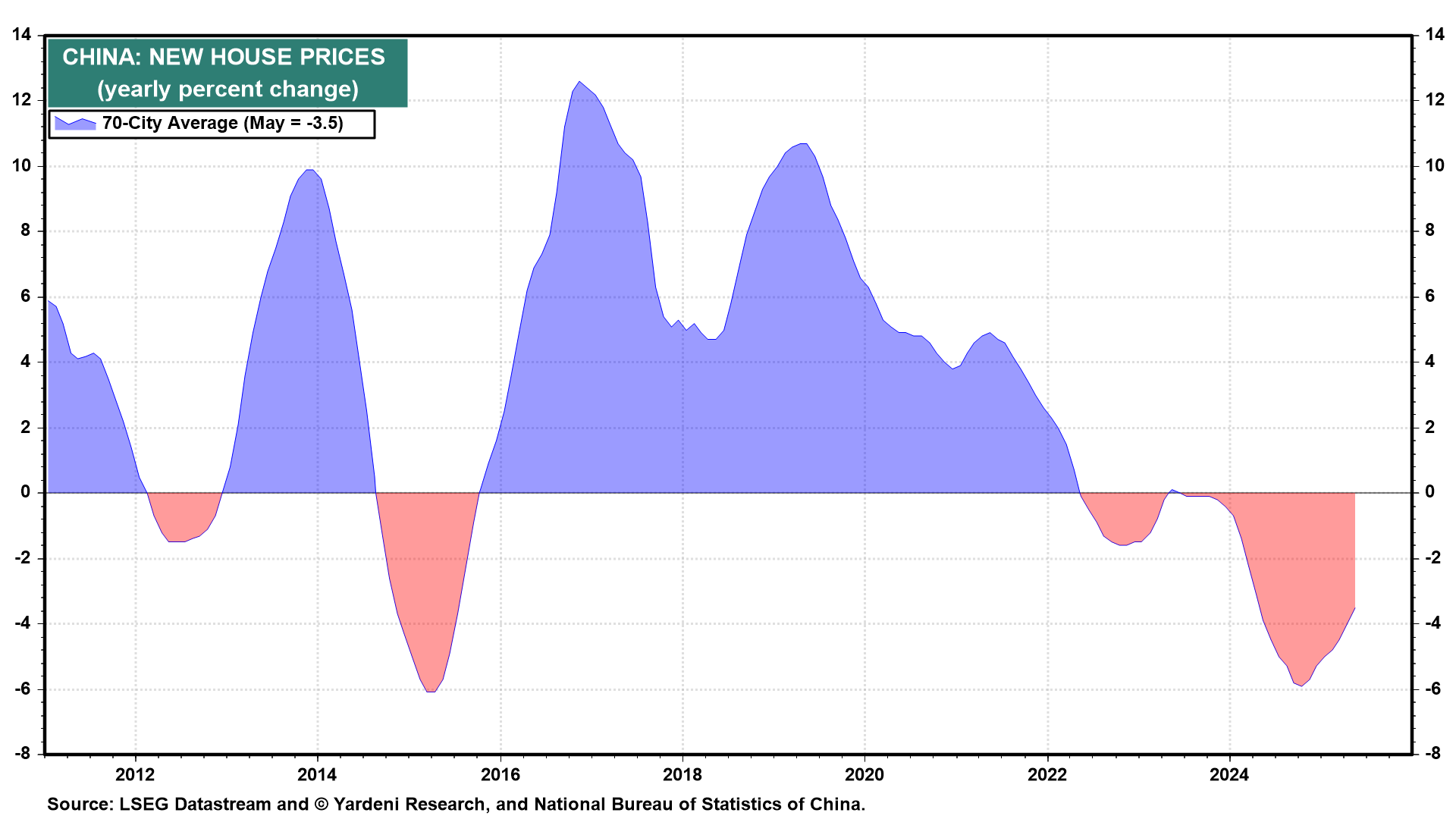

The main drivers of weak household confidence—the property crisis, which is eroding consumers’ wealth, and disappointing wage growth, hurting their incomes—show no signs of improvement.

“Things are not getting much worse, but they will probably not get better without more government support,” warns Larry Hu at Macquarie Group.

(2) Wage growth is lackluster. In a recent report, Jeremy Stevens, Beijing-based Asia economist at Standard Bank, found that only three of the 16 sectors he analyzed saw wages growing faster than GDP since 2020—information technology services, mining, and utilities.

Slowing wage growth only seems to be strengthening the saving-over-spending preference that Xi has been struggling to reverse for more than 12 years now. Like many East Asians, mainlanders are culturally predisposed to save. Compounding things in China is spotty access to good insurance coverage, making healthcare and elder care more expensive. A dearth of social safety nets means households bear the lion’s share of retirement costs. Higher education bills are rising, too.

(3) Real estate values are falling. China’s new-home prices across 70 cities dropped the most in seven months in May—down 0.22% m/m from April. Used home values weakened 0.5%, the steepest decline in eight months. By value, residential sales fell 6.1% y/y in May. More troubling, perhaps, the 12% slump in real estate investment suggests stimulus isn’t gaining traction.

Falling real estate values are the main determinant of household wealth levels in Asia’s biggest economy. Also, the debt troubles plaguing property developers mean scores of giant apartment complexes around the nation remain unfinished. This means millions of Chinese face mortgage payments from homes they can’t live in yet.

(4) Chinese consumers continue to prioritize saving over spending. In its latest quarterly survey—covering the October-December 2024 period—the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) found that 61.4% of mainlanders would rather save money than spend or invest it. This reading has been north of 60% since late 2023.

(5) Economic growth is unbalanced. Speaking to the lopsided state of China’s financial system, central government stimulus efforts only appear to be stabilizing property markets in some top-tier cities, including Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. Lower-tier cities, not so much. One reason is the dire state of local government finances. Already burdened by trillions of dollars in debt, municipalities have less fiscal space to support local economies.

Wage gains, meanwhile, continue to lag the rather optimistic noises emanating from Xi’s Communist Party. China has the economic equivalent of long Covid, argues Stevens at Standard Bank. He calculates that disposable income in the 1.4 billion-person nation is half what it was before the pandemic arrived in 2020; it’s now growing just 5% per year.

All this suggests that Xi’s glacial pace of recalibrating growth engines is coming at a great cost—and a steadily growing one.

In 2013, when Xi formally became China’s strongest leader since Mao Zedong, he pledged to let market forces play a “decisive role” in economic decision-making. Since then, Xi’s promised reform drive too often has taken a backseat to current events. Here are a few cases in point:

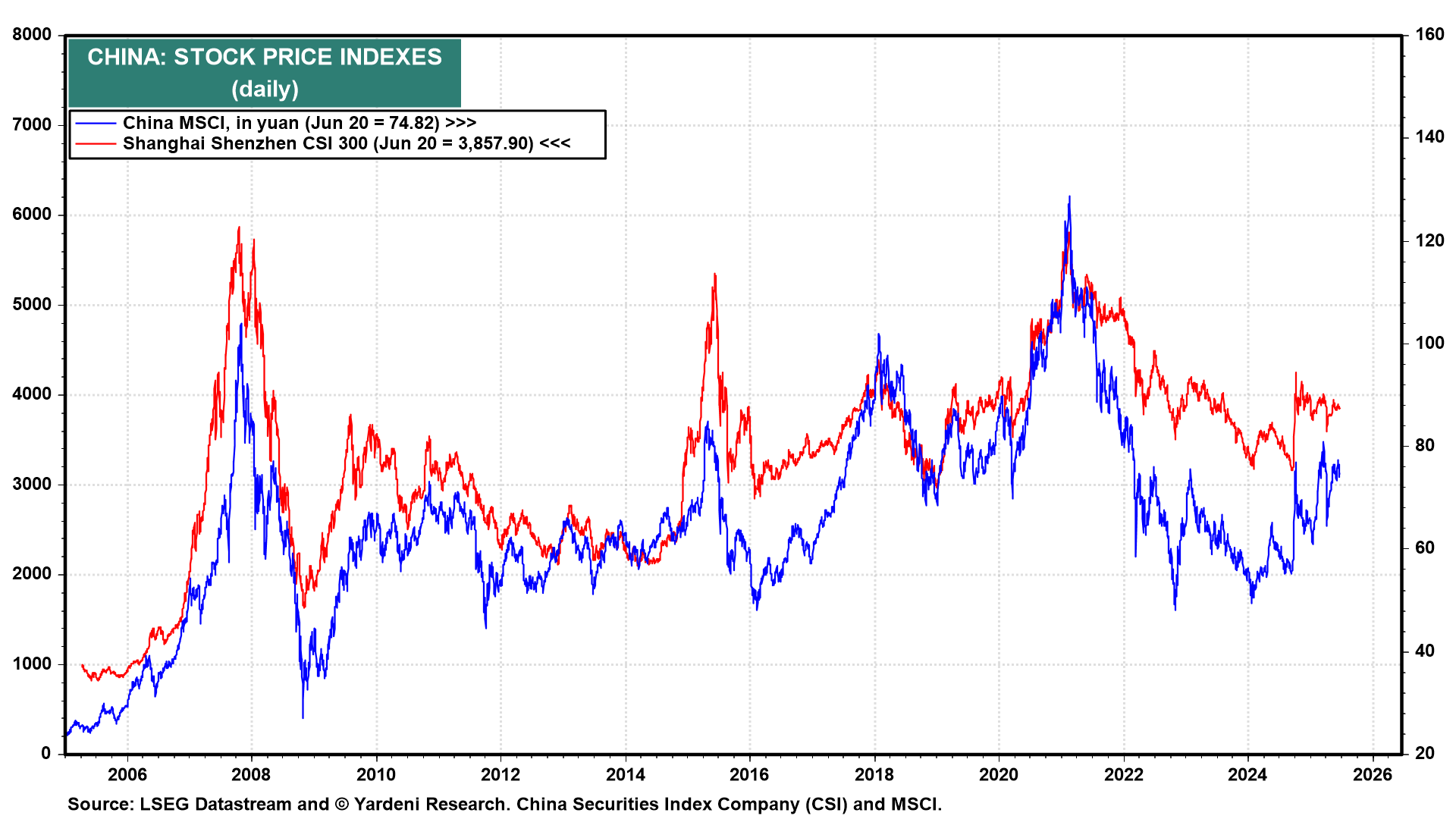

(1) Treating the symptoms. Take the summer of 2015, when Shanghai stocks lost nearly a third of their value in just three weeks. That prompted an all-of-government response, particularly as China’s rout slammed bourses from Tokyo to London to New York and fueled contagion fears.

Beijing scrambled to slash official interest rates, reduce reserve requirements, and loosen rules on leverage. It suspended trading in thousands of listed companies and delayed all IPOs. It allowed apartments to be used as collateral to buy shares and encouraged households to buy stocks out of a sense of patriotism.

What Team Xi didn’t do was use the episode to hasten steps to strengthen capital markets, increase both government and corporate transparency, or make the yuan fully convertible. Nor did Xi’s inner circle accelerate moves to rein in the inefficient state sector to increase innovation, productivity, and disruption.

(2) Undermining tech. When the pandemic hit in 2020, all bets were off again for economic retooling. Yet then Xi went the extra mile to derail reforms with a counterproductive campaign against China’s internet giants. The wealth-destroying putsch started with Alibaba (NYSE:) founder Jack Ma and snowballed from there.

Fast forward four-and-a-half years, and China’s tech industry continues to keep a low profile, unsure when, where, and why Xi’s regulators might pounce.

Xi, of course, has put some huge wins on the scoreboard. The “Made in China 2025” extravaganza he rolled out in 2015 indeed is increasing China’s footprint in artificial intelligence, biotechnology, electric vehicles (EVs), renewable energy, semiconductors, and other vital sectors.

(3) Startup potential. Between the runaway success of EV-maker BYD and AI sensation DeepSeek, Xi has reason to celebrate. Fresh off ruining Elon Musk’s 2024 by beating Tesla (NASDAQ:) in sales, BYD is now testing an EV battery with a driving range of nearly 1,200 miles. And its Seal sedan is aimed directly at Tesla’s Model 3 line of vehicles.

But the economy underlying China Inc. is being hamstrung even more by Xi’s neglect than by Trump’s tariff regime.

If Xi had acted faster to pivot from exports and runaway investment to domestic demand-led growth, China’s economy could have deflected many of the direct hits from Trump’s tariffs. If he had moved with greater alacrity to make the PBOC independent, unshackle the yuan, and reduce the dominance of state-owned enterprises, Chinese exporters and their employees might care less about Trump’s tariffs and both consumer and business confidence might be greater.

The steps needed for Chinese consumption aren’t a mystery. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), after all, has been imploring Xi to get serious about increasing household confidence in China’s economic future.

In an early 2023 report, IMF economists Diego Cerdeiro and Sonali Jain-Chandra explained that “an ambitious but feasible set of reforms can improve these prospects, importantly in a way that is inclusive by raising the role of household consumption in demand. Reforms such as gradually lifting the retirement age to increase labor supply, strengthening unemployment and health insurance benefits, and reforming state-owned enterprises to close their productivity gap with private firms would significantly boost growth in the coming years.”

(1) Tricky demographics. Now, thanks in part to Xi’s glacialism, an aging and shrinking population is its own headwind, hitting the shaky property market. In a June 16 report, Goldman Sachs said “a falling population and slowing urbanization suggest decreasing demographic demand for housing” in the years ahead.

The dynamic, Goldman Sachs noted, will keep housing demand in Chinese urban centers below 5 million units per year on average. That’s just one quarter of 2017’s 20 million units.

China’s population has been shrinking for three years now. It’s likely to dip below 1.39 billion by 2035, says Tianchen Xu of the Economist Intelligence Unit, noting that China also faces problems at both ends of the lifecycle: waning fertility and growing ranks of the elderly.

This trajectory alone, notes Goldman Sachs, could reduce demand for homes by 0.5 million units every year for the rest of this decade, with the demand erosion accelerating during the 2030s—and with increasing side effects.

Older Chinese don’t consume anywhere near as much as those in their 20s and 30s, a fact that exacerbates deflation. A combination of high living costs, job insecurity, and inadequate safety nets has families choosing to have fewer kids. Beijing’s move in 2016 to scrap the one-child policy was too little, too late to change that.

(2) Tariff wildcards. An added wildcard is what Trump does with tariffs. If he hits China with bigger and bigger import taxes, Chinese GDP growth could head toward 4% a year or perhaps even into the mid-3% range that UBS has predicted since April.

Might Trump grow impatient that Beijing isn’t rushing to sign the trade détente that he’s been touting in recent weeks? As Trump World’s fragile handshake deal remains unsealed, there are reports that China has yet to resume the flow of rare-earth minerals to the extent that Trump had assured Americans it would. At the same time, China hasn’t renewed licenses for US defense companies’ use of the magnets.

The fact that China and Iran are allies could now become a flashpoint in Washington-Beijing relations. That’s particularly the case if Trump believes Xi’s party isn’t heeding US pleas to convince Tehran to keep the Strait of Hormuz open to tanker traffic.

Another challenge is that a decade-plus of prioritizing stimulus over reform is reducing the impact of spending jolts. Massive infrastructure projects are generating fewer multiplier effects. The dire state of local-government finances leaves limited fiscal space to deploy old-economy GDP boosters sufficient to increase demand.

(3) Stimulus, interrupted. There are signs, too, that the stimulus tools that have been working are running short of resources. Beijing’s trade-in subsidies aimed at supporting sales of EVs and other fuel-efficient autos have been put in neutral in at least six provinces—including Guangdong, Henan, and Zhejiang—in part because funds are drying up.

Yet drastic measures are needed to get a critical mass of Chinese to open their wallets. Acting boldly to stabilize the property sector is an obvious step. The drip, drip, drip of bad news on weak home prices and potential defaults by giant developers is weighing on sentiment broadly.

Japan’s deflationary “lost decade” was the result of foot-dragging on getting bad loans off banks’ balance sheets. Many worry that China is falling deeper into this sort of “balance sheet recession.” This includes Richard Koo of Nomura Research Institute, who’s credited with popularizing the phrase.

The same goes for cleaning up local government balance sheets. Faced with crushing debt loads, most of China’s 23 provinces have less scope to invest in infrastructure, education and healthcare, and the local ecosystem to produce the next Alibaba, BYD (SZ:), or DeepSeek.

Xi’s government also has displayed a bewildering disinterest in importing the polices that have morphed Hong Kong into a global finance hub. Rather than emulate the city’s laissez-faire ethos, Beijing has sought to remake Hong Kong in its own opaque image.

Nor does Xi’s inner circle borrow from Hong Kong’s stimulus playbook, featuring mass cash handouts that boost confidence and buy officials time to recalibrate growth engines. Such a jolt to spending power might help repair the lingering damage from Xi’s draconian ”zero-Covid” lockdowns in 2022.

Luo Zhiheng of Yuekai Securities thinks offering services-sector consumption vouchers would help, along with increasing the number of public holidays. To bolster sentiment in the longer run, Luo says it’s time that Beijing more than doubled pension payouts. That, he argues, would encourage households to save less and consume more.

Trump’s tariffs and bluster are sending headwinds China’s way. Exports to the US plunged 34.5%y/y in May. But the real impediments to economic growth in China are homegrown—and festering as we speak