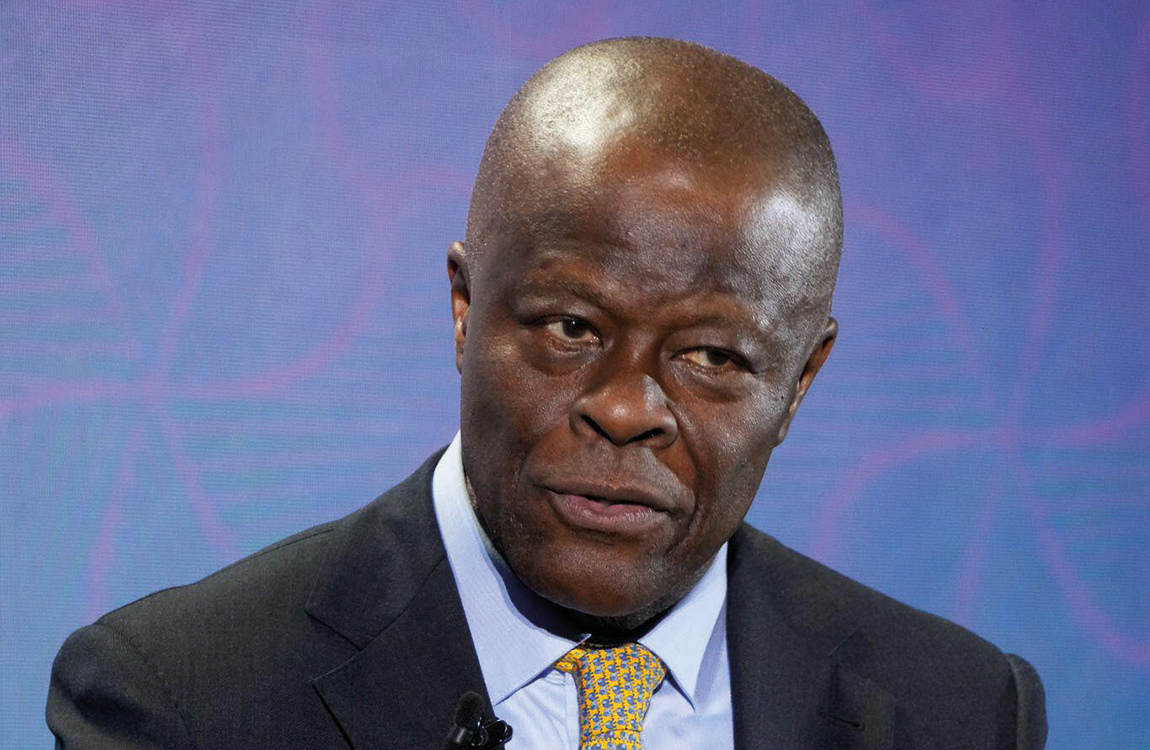

At 68 years of age, Spike Lee has lived through several phases of his career. There was his incredible, nearly peerless run that began with “She’s Gotta Have It” and ended with “Bamboozled.” Then there was the fallow period, where he made triumphs like “25th Hour” and underwhelming pictures like “She Hate Me,” along with more movies whose budgetary restrictions appeared plainly on screen. With the success of “BlacKkKlansman,” “American Utopia,” and “Da 5 Bloods,” Lee has experienced a recent resurgence. At this point, in fact, you’d be right to wonder what’s left for Lee to achieve. In a bid to find a way forward, with “Highest 2 Lowest,” an exceptional piece of personal filmmaking that might be Lee’s most energetic film since “Inside Man,” the director returns to two early loves: Akira Kurosawa and Denzel Washington.

Similar to Lee’s public persona, “Highest 2 Lowest” is a chaos agent of a movie, the kind of lavish, unpredictable crime thriller that zips when you expect it to zoom. It begins on a slow and sleepy climb, worrying the viewer that the director might’ve finally lost his touch, before exploding into a manic filmmaking cornucopia that includes some of the best images of Lee’s long career. “Highest 2 Lowest” is a faithful adaptation of Kurosawa’s “High and Low,” until it’s not. It’s a long-winded procedural, until it’s not. It’s a movie that amounts to old men yelling at clouds, until it’s not. It’s the worst of Washington and Lee’s five collaborations—a partnership that began with the rhapsodic jazz film “Mo Better Blues”—until the film suddenly plants itself as among their best.

Unabashedly epic, fearlessly funny, and proudly Black, “Highest 2 Lowest” might derive from a Japanese filmmaker. But its soul clearly resides in Lee.

Premiering out of competition at Cannes, the first half of Lee’s frantic film pulls you into panic. Initially William Alan Fox’s evasive script dutifully follows the basic plotting of Kurosawa’s classic. Washington is the millionaire CEO of Stackin’ Hits records, David King, a record producer renowned for his uncanny ear for music. Though he sold off some of his stake in his label years ago, he’s now angling to buy back control—even if it takes all his money. His plan is stymied when kidnappers attempting to apprehend his son Trey (Aubrey Joseph), mistakenly commandeer Kyle (Elijah Wright), the son of his friend and chauffeur Paul Christopher (Jeffrey Wright). The situation forces King and his wife Pam (Ilfenesh Hadera) to risk everything to save Kyle.

Though Lee’s film is hitting the beats that elevated Kurosawa’s picture, something here is off. The pacing is laborious; the characters in the frame appear distant; the lighting and framing seem staid and sterile; the score chews through each and every scene. You’d think Lee, who watched his remakes “Da Sweet Blood and Jesus” and “Oldboy” be ravaged by critics for being shot-for-shot retellings, would be reluctant to repeat past mistakes. Unlike those films, however, the slow start here appears to be intended.

The first half “Highest 2 Lowest,” therefore, is a kind of endless wilderness, where Lee and Washington, now reunited after nearly 20 years, try to reconstruct their magic by returning to their roots. See, King once was cutting edge, but like many artists, the times and the trends have passed him by. He lives high above the masses in a kind of ivory tower, surrounded by relics of the past: Posters and paintings featuring Joe Louis, George Foreman, Muhammad Ali, and Toni Morrison line his walls. Cinematographer Matthew Libatique’s observant lens sparingly opts for closeups, mostly employing wide frames to consume the amount of stuff in King’s abode. At some point we get tired of seeing just how much wealth this family possesses, causing one to become disinterested in their plight.

While it’s clear the blocking and framing are meant to ape Kurosawa, the filmmaking also speaks to Lee’s own insecurities. How can the director remain fresh and vital on today’s cinematic landscape? What does creative success look like when an entire industry is defined by making a billion dollars at the box office? As King shares his gripes about AI, follower counts, and virality now guiding his industry, his words sound like they’re coming directly from Lee’s own mouth.

Once we leave the suffocating surroundings of King’s home—as Kurosawa did before, abandoning the tycoon’s spare, quiet, palatial home for the chaotic streets below—“Highest 2 Lowest” evolves from a Kurosawa homage into a full blown Spike Lee adventure. King descends from his penthouse back into the city to pay the ransom to the kidnapper and aspiring rapper Yung Felony (ASAP Rocky). What comes next is maybe the best, most controlled sequence of Lee’s career. Composer Howard Drossin’s once placid score ramps into a frenzy, twirling with the ferocity of the winding 4 train King rides with a black Jordan bag full of 17.5 million Swiss Francs strapped to his back. Within the train, belligerent Yankees fans disparaging Boston sports teams provide further ambience. Outside the train several neighborhood events pass by, particularly a Puerto Rican day festival where Rosie Perez and Anthony Ramos present several legendary musicians. Their rhythmic music seamlessly replaces Drossin’s uptempo suite, creating a barrage of images that not only combines these charged crowds with the drama of King navigating the train. But also exemplifies Lee’s assured ability to contort aesthetics, switching back and forth from the film’s prior digital sheen to a gritty filmic quality that visually matches Washington and Lee’s back to basics mantra.

Several other aspects of “Highest 2 Lowest” also change in its riotous second half. Lee’s uses less and less of the classical score, relying on sweaty tracks by James Brown to fuel the film. The director also begins opting for close-ups, allowing the actors to ratchet up the crime thriller’s inherent intensity without sacrificing the picture’s unflinching splendor. Wright in particular is given greater space to breathe, offering the kind of hardened salt-of-the-earth persona that brings Washington’s King closer to home. In fact, it’s no accident that Christopher and King need to return to their old neighborhood to settle the score, or that a vital clue is delivered by King returning to his past music listening habits. Lee similarly returns to what works, delivering the type of stylistic excess that makes him among the most idiosyncratic filmmakers of his generation.

Every decision Lee makes in “Highest 2 Lowest,” comments upon his reteaming with Washington. While the pair have made four prior films together, those occurred when Washington was either young or could still pass for middle age, and wasn’t routinely playing action heroes and weary loners. This is the first time they’ve teamed as older men. Lee taps into Washington’s newfound experiences, crafting an intense sequence that involves a rap battle between King and Yung Felony. Similar to the entirety of his performance, Washington wields his unmatched sense of timing to bring out surprising choices. Rocky holds his own in this faceoff, providing Washington the type of anger that allows him to hit that extra gear.

And while many will come to “Highest 2 Lowest” craving the angst of Kurosawa’s masterpiece, for once Lee isn’t setting out to copy what was great before. He is using the past as a starting point to launch into what may be the final phase of his career. He is wielding a plethora of inspirations—musical, cinematic, and historical—to reunite with an old friend. He is making a Spike Lee joint. And it’s exceptional.

This review was filed from the premiere at the Cannes Film Festival. It opens August 22.