GHAI: Why pork barrelling is unconstitutional

When I first came to Kenya – in 1988 – I travelled on a major road in a state of serious disrepair. I was told, “It’s like this because these people didn’t vote for Moi.”

I had a strong sense, during the constitution-making process, that this sort of behaviour was something that people wanted confined to history.

It is, of course common for newly elected governments to say things like, “I shall be the President [Prime Minister] for all our people.” Former US President BidenFormer US President Biden and current President Donald Trump both said it after being elected, and Kamala Harris also said it, hoping to be elected. Our President is still saying it. True, he has also said things that sound good in terms of benefiting parts of the country that have been marginalised.

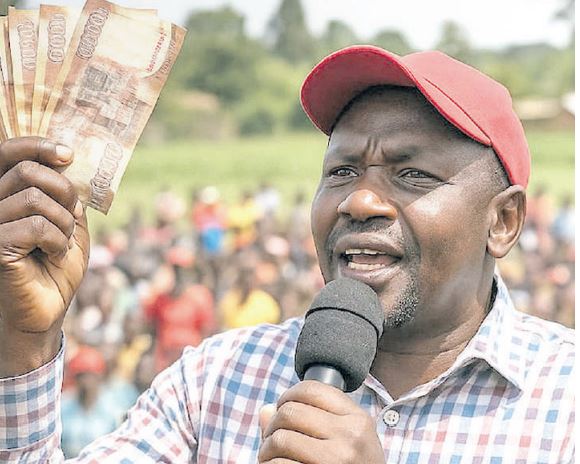

But it has become clear in recent weeks that this type of behaviour has not been banished. People have been saying things such as, “We have got the benefit of government projects since we supported the President.”

We must recognise that politicians want votes or other forms of support. The theory of democracy and accountability is that if government policies and projects get public approval, this will lead to votes. But actions such as punishing voters by failing to deliver, or depriving them of valid and needed projects are going too far.

When it comes to projects for votes the American have a name for it. “Pork Barrelling”, or even just “Pork”. It refers to politicians getting national funding for projects in their own areas in order to win their votes for a bigger bill. They may do it, for example, by saying to, “I’ll vote for your Bill only if you make sure this project goes ahead in my constituency.” It’s not restricted to the US.

Is it wrong? An Australian commentator said last year, “[This] misuse of public funding is an economic rip-off because it wastes public money that governments could spend elsewhere. There’s also an electoral rip-off because it undermines our trust in government and short-changes our democracy.”

The constitution

I want to approach this from the constitutional angle. The constitution does not have a provision saying, “The President must not discriminate between counties or communities on the basis of how they voted or may vote.” But I hope to show that such a practice violates the design of the Constitution.

The most obvious issue is that of democracy – a national value in Article 10. More specifically, Article 38 recognises every citizen’s right to vote. But what use is a vote if you are going to be punished for the way you exercise it? This sort of approach turns democracy into even more of a gamble means that – not only may you not get a good government, you may actually be penalised for the way you voted.

In fact what is happening now is most like pork barrelling – it is not about punishing people for the way they voted so much as using projects to get people on government’s side, to try to secure their votes for the next election. But one must ask – are other communities deprived of benefits because they cannot be expected to vote for the president, as the Australian commentator suggested?

The constitutional financial system

There is a coherent conception about public expenditure embedded in the constitution. Money is to be used in a rational way, based on evidence, and on need, and planned well in advance, so there can be public involvement and understanding of what is happening. Politics – in the way people use that word here, to mean a focus on who gets elected and how to persuade the people to vote – is not really supposed to be part of the process.

Article 201 sets out the principles that include: expenditure being used to promote “equitable development”, public money is to be used prudently and responsibly, and financial management must be responsible.

Devolution

Someone wrote last weekend that devolution was supposed to deal with this issue. And, indeed, that is an aspect of devolution. It is supposed to bring decision-making, and the money needed to carry out decisions, closer to the people. That way decisions ought to be more relevant, and money be allocated where it will have the best effect. The electorate at the county level should be able to judge whether money is being used appropriately – which includes not being used to buy votes or to punish a community for how it voted.

Devolution means that the national government should not spend money on certain things that are the responsibility of the counties. A clear example is markets – one of the functions of counties, without any national government function that seems to permit it to build a market.

How money reaches counties is a major issue in the constitution. Article 203 sets out more principles on this – they include meeting the needs of counties, reducing economic disparities between them, and having stable and predictable revenue. How would presidential favours to get votes fit here?

There is an elaborate process. First a decision must be made as to what proportion of the national revenue is to go to the counties collectively. This decision is made by Parliament but must ensure that a minimum of 15 per cent goes to the counties, and must take account of recommendations of the Commission on Revenue Allocation. This commission is a sort of hybrid – political parties nominate most of its members, but they cannot be MPs, and must also have extensive relevant experience.

Dividing revenue between counties is done on the basis of a Senate resolution – but they must take into account the recommendations of the CRA and the principles of Articles 201 and 203. The National Assembly can change this – but only by a super-majority.

When we turn to the Equalisation Fund, we see that it is limited in its use. It must be used only to provide basic services to areas that enjoy a lower level of those services than generally in the nation, and the criteria for identifying those areas are decided by the CRA; the national government may use those funds only if Parliament has passed a law deciding how they are to be used.

Our version of pork barrelling clearly undermines this set of provisions intended to ensure that money is used according to certain principles and, above all, according to need.

Budgeting

Budgeting at the national level begins in August and is supposed to include public involvement and input, and well-informed decision-making. Short-term decision-making to entice voters is outside both this system of budgeting and law making. It cannot be attributed to any of the ways in which money is supposed to be spent at local levels – not part of the “equitable share”, nor of the Equalisation Fund, nor a grant, conditional or not, to counties, nor apparently part of the national government’s budget made in accordance with the constitution. It may even be, at least if spent on something like a market, not something the national government is allowed, in any way, to spend money on.

Bribing individual voters is of course a crime. The potential of government projects to be a sort of wholesale bribe is clear. In the UK there is a “period of sensitivity” in the weeks leading up to an election, “When governments, ministers and civil servants will exercise caution in making announcements or decisions that might have an effect on the election campaign.” By contrast, it seems that here there is no compunction about behaviour that might affect voters – indeed; it is embraced as an idea, and not just before elections but also virtually at any time. As a court held this week, early campaigning is a bad, they said unconstitutional, thing. Pork barrelling is another reason, I suggest.