BMC Women's Health volume 25, Article number: 312 (2025) Cite this article

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a significant public health and human rights issue globally. In Ethiopia, the true extent and associated factors of GBV among women remain inadequately synthesized. Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis was aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of GBV and identify its associated factors among women in Ethiopia.

A comprehensive search of literatures was conducted using PubMed, Medline, HINARI, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google scholar from November 10, 2024 to November 30, 2024 following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Additional studies were searched using a reference of identified articles. Studies reporting the prevalence of GBV and associated factors among women in Ethiopia were included. Data were extracted using a standardized form and the quality of included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Inspection of the Funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to evaluate the evidence of publication bias. The heterogeneity of the included studies was evaluated using Cochrane Q and I2 test. A random effects meta-analysis was computed to determine the pooled estimate of gender-based violence using STATA 17.

A total of 19 studies with 23,787 study participants were included in this review. The meta-analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of gender-based violence among women is 51.34% (95% CI: 44.48–58.19). Factors significantly associated with GBV included monthly pocket money received from their parents, urban residence, experience of sexual intercourse, young age, alcohol consumption, being single in marital status, tight family control and number of sexual partners.

The prevalence of gender-based violence among women is found to be high, which is a significant concern. Identified associated factors highlight potential areas for targeted interventions and prevention strategies. Further research is needed to understand the complex interplay of these factors and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

CRD42024619618.

A type of violence known as gender-based violence is one that targets individuals based on their gender and represents a significant global public health problem. It encompasses a wide range of abuses (sexual, physical and psychological) and harmful practices directed at individuals based on their gender, with women and girls disproportionately affected. This violence is now widely recognized as a serious human right violation and anticipated to result in short-term and long-term health problems, such as: sexual, physical, psychological and reproductive health consequences [1,2,3,4,5]. Gender based violence survivors dealt with the traumatic stress by outmigration (leaving their residences), seeking care at healthcare facilities, self-isolation, being silent, dropping out of school, and seeking counseling [2,3,4, 6].

The prevalence of gender-based violence is high in Sub-Saharan Africa. The overall prevalence of gender-based violence ranged from 42.3% in Nigeria to 67.7% in Ethiopia [7]. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis among female youths in educational institutions of Sub-Saharan Africa revealed that the prevalence of lifetime GBV was 52.83% [7]. A similar study in Sub-Saharan Africa also showed that the pooled prevalence of lifetime GBV was 44% [8].

As various literature reveled, gender-based violence against women was high in different parts of Ethiopia. A cross-sectional study conducted among high school female students in Debre Markose, Baso, Mikewa Town, Aleta Wondo, Wolaita Sodo and East Hararghe zone showed that the life time prevalence of GBV was 67.7%, 47.2%, 46.6%, 68.2%, 63.2% and 55%, respectively [4, 9,10,11,12,13]. A cross-sectional study conducted among elementary and high school night female students in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia revealed that the overall lifetime prevalence of gender-based violence was 71.1% [14]. A cross-sectional study conducted among internally displaced women found that a one-year prevalence of gender based violence was 37.9% [15]. A study conducted among college students in Dessie and Gonder city showed that the prevalence of gender-based violence was 62.6% and 35.1% respectively [16, 17]. A cross-sectional study of gender-based violence among women in North Shewa zone, Amhara showed that the magnitude of GBV was 58.0% [2]. A cross sectional study among women of reproductive age in Tigray showed that the overall prevalence of gender based violence was 43.3% [5]. A study conducted among marginalized women in Southern Ethiopia found that the prevalence of GBV was 20.9% [18]. A cross sectional study among female students at Wolkite University showed that the overall prevalence of gender-based violence was 46.2% [19]. A cross sectional study of gender-based violence among sex workers from 16 towns in Ethiopia revealed that 28.1% was experienced GBV [20]. A nationwide study conducted in Ethiopia showed that the lifetime prevalence was 30% [21]. A systematic review and meta-analysis among high school female students in Ethiopian found that the prevalence of lifetime gender based violence was 45.25% [22]. A systematic review and meta-analysis among female students in Ethiopian higher educational institutions revealed that the prevalence of lifetime GBV was 51.42% [23]. A meta-analysis among women in Ethiopian showed that the overall pooled lifetime prevalence of gender based violence was 46.93% [24].

The researchers also found that the following factors were associated with the likelihood of gender-based violence: younger age [5, 15, 20, 25], alcohol consumption [12, 13, 15, 25], monthly pocket money received from their parents [11], witnessing parental violence [7, 13], educational status [2, 7, 25], limited decision-making skills [25], living in urban area [2, 7], substance use including chat chewing and cigarette smoking [7, 25], tolerant and positive attitudes to violence [25], being single in marital status [7, 15], number of sexual partner [2], sexual intercourse history [2, 11, 12, 22] and free discussion [11].

Despite increasing attention on GBV, significant knowledge gaps persist, hindering effective prevention and response efforts. These gaps exist across various dimensions: underreporting, lack of comprehensive data, methodological challenges and limited disaggregated data. Elimination of violence against women is one of the key Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), target 5.2 [26]. Due to this, the prevention of violence against women has long been the focus of attention by several global organizations and countries including Ethiopia. Understanding the true extent of GBV and the factors that contribute to its occurrence is crucial for informing evidence-based policies and interventions tailored to the Ethiopian context. While some regional systematic reviews have touched upon GBV in Sub-Saharan Africa, a focused and comprehensive synthesis of the evidence specifically within Ethiopia is needed to provide a clear picture for national stakeholders and guide targeted action. Several primary studies were conducted but there is inconclusive finding and limited systematic review and meta-analysis of the pooled prevalence of gender-based violence. This study aimed to assess the pooled prevalence of GBV and its associated factors among women in Ethiopia. Furthermore, this synthesis of evidence is essential for informing national policies, designing targeted interventions, and guiding future research efforts aimed at preventing and addressing GBV in Ethiopia.

This systematic review and meta-analysis were carried out and described in compliance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [27] (S1 Table). The systematic review was certified on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with the specific number CRD42024619618.

This study conforms to the population, exposure, comparison, and outcome (PECO) framework with (P) women experienced gender-based violence, (E) being women, (C) the reported reference group for each factor in each study, (O) the prevalence and associated risk factors of gender-based violence in Ethiopia. Research works that execute the following inclusion criteria were considered: [1] Quantitative or qualitative or mixed methods studies that reported information on gender-based violence in Ethiopia were included; [2] Both peer-reviewed published and unpublished articles (pre-prints and grey literature) were incorporated; [3] Articles written and published in the English language were screened.

Studies that did not include data on gender– based violence were excluded. Besides, reports, conferences, case reports, articles without full access, reviews, and guidelines were excluded from the study. Articles written and published other than English language and studies including both males and females without reporting data separately for females were excluded, as well.

A comprehensive search of literatures was conducted using PubMed, Medline, HINARI, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google scholar from November 10, 2024 to November 30, 2024. The search was done using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) with the following search terms: “magnitude”, “prevalence”, “epidemiology”, “proportion”, “female”, “girl”, “women”, “woman”, “gender-based violence”, “domestic violence”, “associated factors”, “risk factors”, “determinants” and “Ethiopia”. A combination of different Boolean operators (AND, OR), and truncation were used to develop the search strategies. Unpublished studies with epidemiological data on gender-based violence in Ethiopia was searched. The references of already identified relevant studies were also screened.

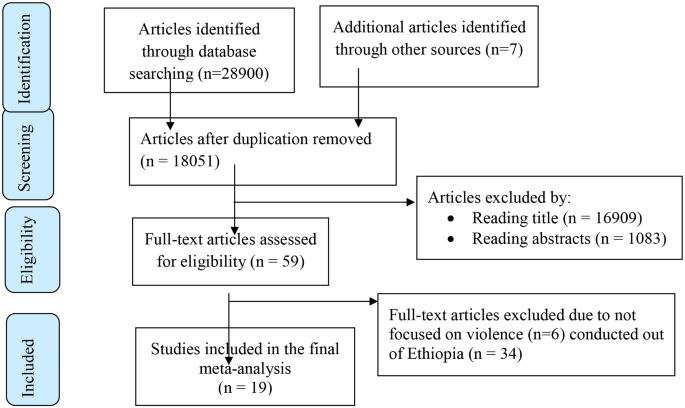

All the identified studies were sent to EndNote X9 reference manager software and duplicates were deleted. Two reviewers (BWY and BBY) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of remained studies. To confirm their eligibility, the full texts of studies were assessed according to the preset criteria. Differences between the two reviewers were settled by discussion. The study selection and screening processes were presented using the PRISMA flow diagram.

To assess the quality of each study, the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) tool adapted for cross-sectional studies quality assessments was employed. The methodological quality of all the included studies were independently assessed by two reviewers (BWY and BBY). The difference between the two authors was addressed through communication. The assessment instrument contains of 10 points (stars) in three main parts. The first part of the tool weighted as five points focuses on selection which is the methodological quality of each study. The second part of the tool focused on the comparability of the study which rated two points. The last part is focused on the assessment of the outcomes and statistical tests of the primary study with a possibility of three points. Finally, original studies assessed with a score of ≥ 7 out of 10, 5 to 7 out of 10 and ≤ 4 out of 10 were considered as achieving high, medium and low quality respectively (Table 1).

To extract data from the included studies, a standardized data extraction tool adapted from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) was employed. Accordingly, two authors (BWY and BBY) performed data extraction independently. Disagreements between two authors that arose during data extraction were resolved by communication. The following necessary information was extracted accordingly from each included studies: the name of first author, publication year, study region, study design, study participants, sample size, prevalence of gender-based violence, and associated factors.

The data were extracted using Microsoft Excel data sheet, and imported into STATA version 17. A meta-analysis and qualitative synthesis of the evidence were performed. To determine the associated factors of gender-based violence, meta-analysis was employed. The findings of included studies were presented using table, figures and a forest plot. Heterogeneity among the included studies was evaluated using Cochran’s Q statistic and quantified by I2 statistics, and presented by forest plot. The presence of heterogeneity across the selected articles was considered when p < 0.1 or I2 > 50% [28]. A random-effects model was used to determine pooled estimates as considerable heterogeneity was exhibited between selected articles. To address variations in the primary studies, subgroup analysis was carried out based on publication year.

To evaluate the evidence of publication bias, visual inspection of funnel plots asymmetry and Egger’s regression test were used. Egger’s test regression was assumed indicative of publication bias if a p-value < 0.05 [29]. Nonparametric trim and fill analysis were conducted using the random-effect analysis in case evidence of publication bias was observed [30]. To check the presence of a single study that influence the overall estimate, a sensitivity analysis was conducted [31].

At the beginning of search strategy, a total of 28,907 relevant studies were generated. Following the withdrawal of 10,856 duplicates, 18,051 studies remained. Two authors (BWY and BBY) screened the remaining articles accordingly and result in the removal of 17,992 studies. Then 59 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of the 59 studies, 40 were excluded due to variation in study locations and no pertinent data. Finally, 19 studies were included in the final systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

A total of 19 studies with 23,787 study participants were included in the review. Out of 19 included studies: 17 studies were quantitative cross-sectional studies and two were mixed (quantitative and qualitative) studies. Seven studies were conducted in Amhara region, five studies were conducted in Southern Nations Nationalities and People (SNNPR), two studies were nationwide surveys, three studies were in Oromia region, one study was from Tigray region, and one study was conducted in Harari region. All the included studies were published. All the primary studies scored ≥ 7 out of 10 on the quality assessment point (Table 1).

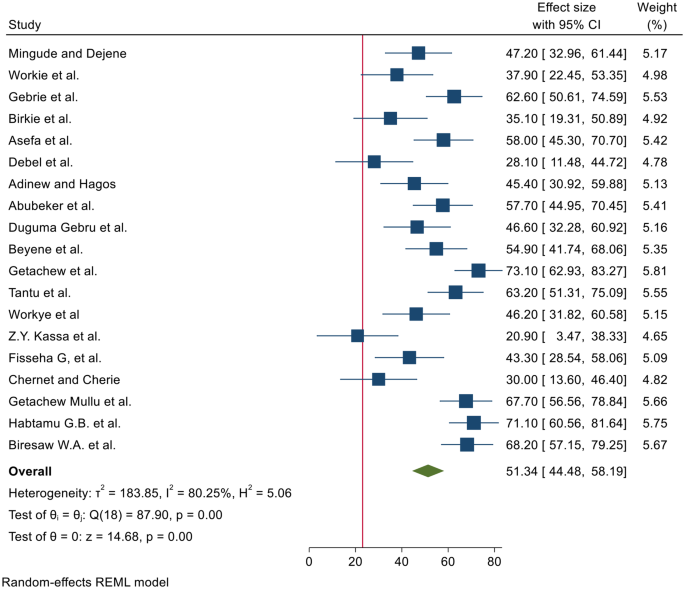

In this study, 19 primary studies with a total of 23,787 women were included. The finding of this meta-analysis revealed that the pooled prevalence of gender-based violence among women in Ethiopia is 51.34% (95% CI: 44.48–58.19, I2 = 80.25%) (Fig. 2).

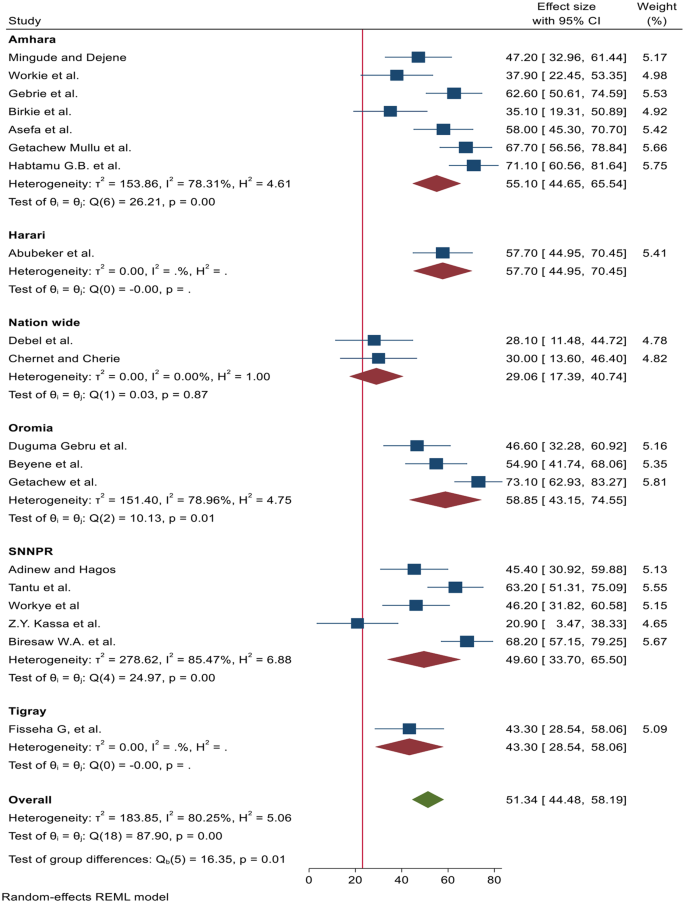

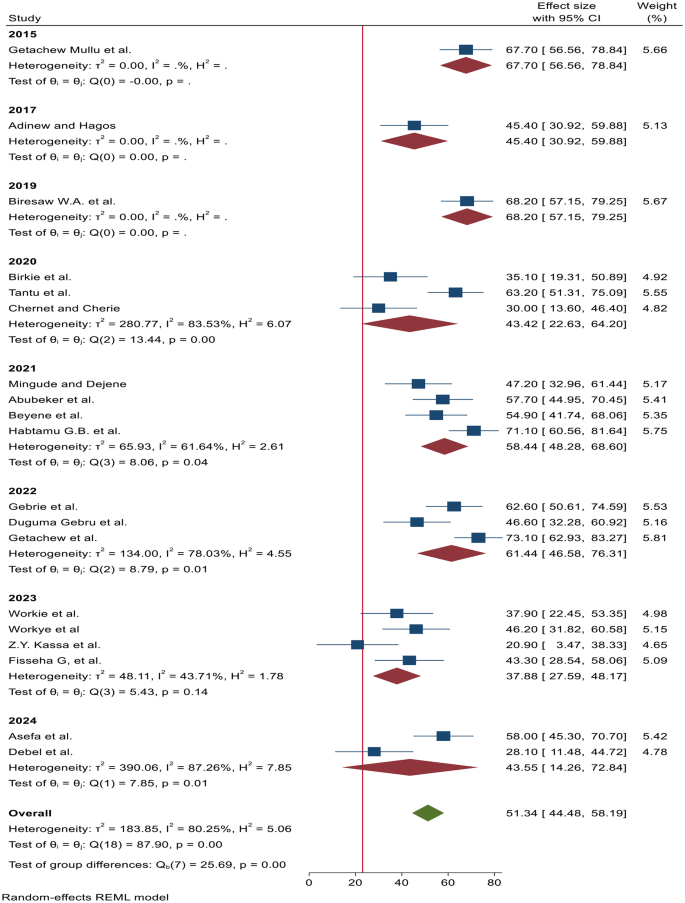

To explore the origin of heterogeneity across the included articles, subgroup analysis was done by regions (Fig. 3) and publication year (Fig. 4).

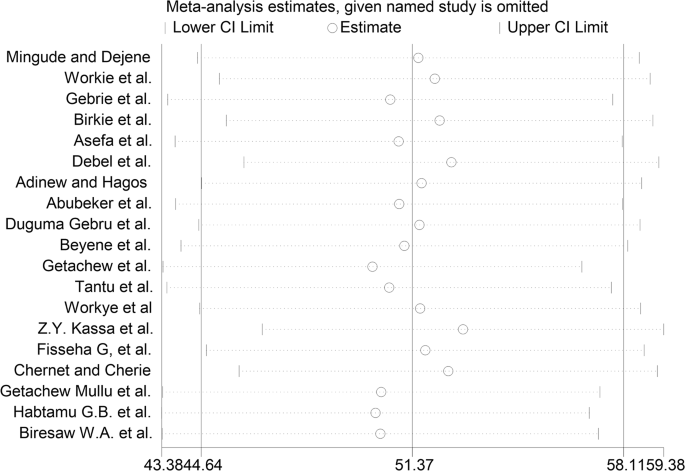

Sensitivity analysis was conducted using the random-effects model. The results of the sensitivity analysis suggested that there is no influential study as none of the points estimate outside of the overall 95% confidence interval for all estimates (Figure 5).

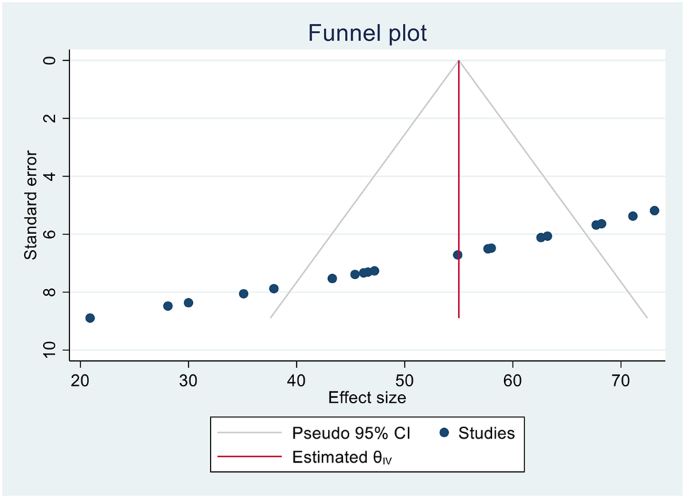

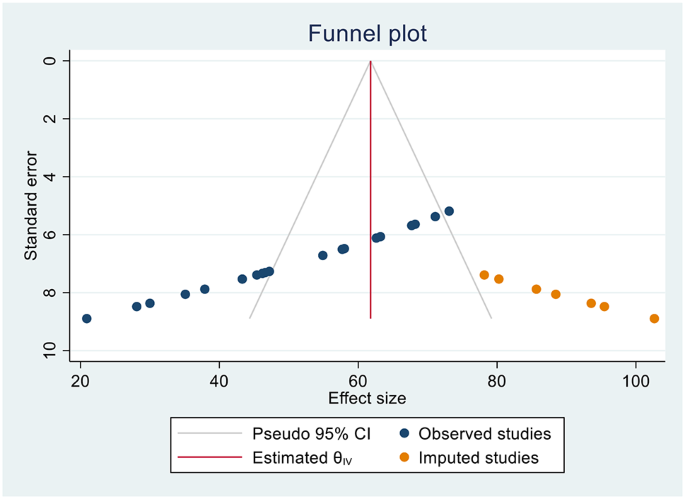

As shown in Fig. 6, the visual inspection of the funnel plot showed that there was publication bias among the included studies, as illustrated by the asymmetrical observation of the funnel plot. As a result, nonparametric trim and fill analysis were conducted (Figure 7).

Based on this meta-analysis, gender-based violence among women in Ethiopia was associated with monthly pocket money received from their parents, urban residence, experience of sexual intercourse, young age, alcohol consumption, being single in marital status, tight family control, and number of sexual partners.

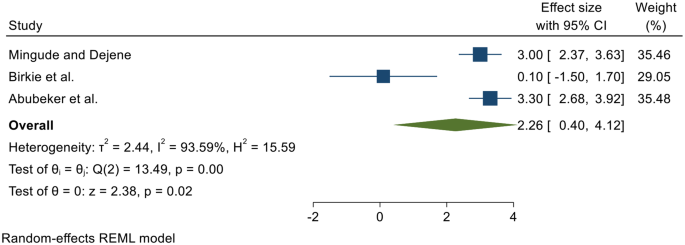

In this study, the pooled OR revealed that monthly pocket money received from their parents increased the odds of females experiencing GBV by 2.6-fold [OR: 2.6; 95% CI (0.40, 4.12)]. The heterogeneity (I2 = 93.59%) is shown in Fig. 8.

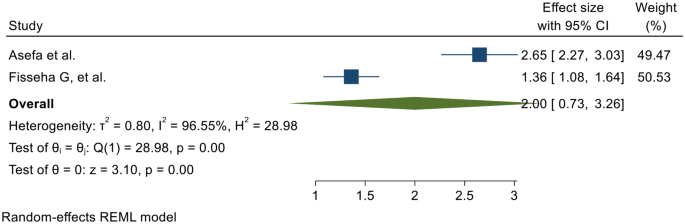

Women live in urban were twice as likely to experience GBV in comparison to those who lives in rural area [OR: 2.00; 95% CI (0.73, 3.26)] with the heterogeneity test, I2 = 96.55% (Fig. 9).

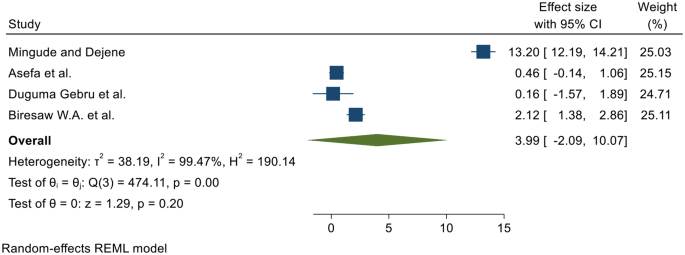

Women who have experience of sexual intercourse were about 3.99 (OR = 3.99; 95% CI: -2.09-10.07) times more likely to have gender-based violence when compared with women who has no sexual intercourse experience. The heterogeneity test (I2 = 99.47%) is shown in Fig. 10.

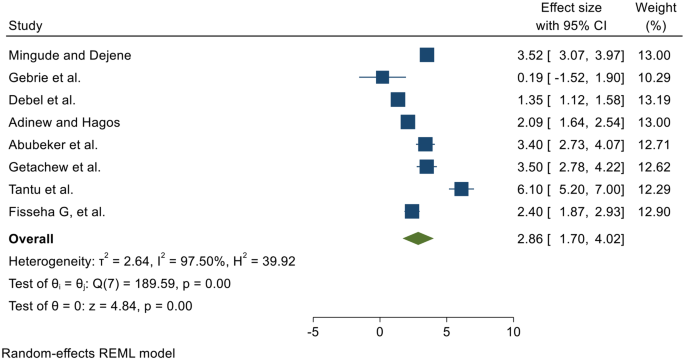

Young age women were nearly three times more likely to experience GBV in comparison to those older women [OR: 2.86; 95% CI (1.70, 4.02)] with the heterogeneity test, I2 = 97.50% (Fig. 11).

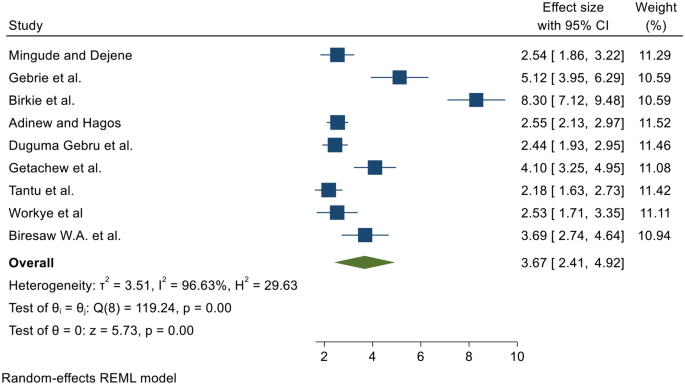

In this meta-analysis, the pooled OR revealed that alcohol consumption increased the odds of women experiencing GBV by 3.67-fold [OR: 3.67; 95% CI (2.41, 4.92)]. The heterogeneity test (I2 = 96.63%) is shown in Fig. 12.

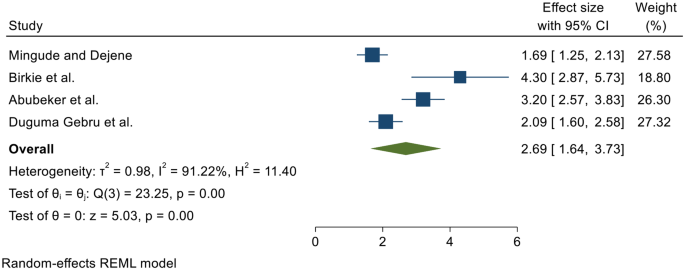

Being single in marital status were 2.69 times more likely to experience GBV in comparison to married women [OR: 2.69; 95% CI (1.64, 3.73)] with the heterogeneity test, I2 = 91.22% (Fig. 13).

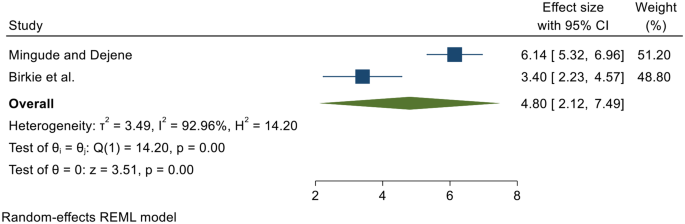

The pooled OR showed that tight family control increased the odds of experiencing GBV by 4.80-fold [OR: 4.80; 95% CI (2.12, 7.49)] with the heterogeneity test, I2 = 92.96% (Fig. 14).

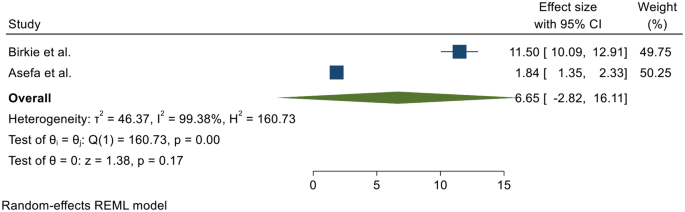

In this review, the pooled OR revealed that number of sexual partners increased the odds of experiencing GBV by 6.65 times [OR: 6.65; 95% CI (-2.82, 16.11)] with the heterogeneity test, I2 = 99.38% (Fig. 15).

Forest plot showing the pooled odds ratio of the association between monthly pocket money received from their parents and GBV among women in Ethiopia

Forest plot showing the pooled odds ratio of the association between urban residence and GBV among women in Ethiopia

Forest plot showing the pooled odds ratio of the association between experience of sexual intercourse and GBV among women in Ethiopia

Forest plot showing the pooled odds ratio of the association between young age and GBV among women in Ethiopia

Forest plot showing the pooled odds ratio of the association between alcohol consumption and GBV among women in Ethiopia

Forest plot showing the pooled odds ratio of the association between being single in marital status and GBV among women in Ethiopia

Forest plot showing the pooled odds ratio of the association between tight family control and GBV among women in Ethiopia

Forest plot showing the pooled odds ratio of the association between number of sexual partner and GBV among women in Ethiopia

This comprehensive study provides a plethora of information on the overall prevalence and associated factors that augment the occurrences of gender-based violence in Ethiopia. The pooled prevalence of GBV among women in Ethiopia is 51.34% (95% CI: 44.48–58.19). The findings showed the pooled prevalence of GBV was high and this high pooled prevalence included more than half of the women experiencing GBV. This magnitude of GBV underscores the urgent need for effective prevention and intervention strategies.

This study is in line with a systematic review and meta-analysis among female students in Ethiopian higher educational institutions revealed 51.42% [23]. This indicates that gender-based violence among women is common in Ethiopia. The finding of this review also revealed nearly the same finding as a study conducted among female youths in educational institutions of Sub-Saharan Africa revealed 52.83% [7]. This implies that gender-based violence among women is a common practice with rampant harmful beliefs and traditions in Africa, particularly Sub-Saharan.

The result of this review and meta-analysis is higher than a systematic review and meta-analysis among female high-school students, which is reported at 45.25% [22]. This variation may be due to the study participant. Similarly, this finding is also higher than a study conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa, which is showed that the pooled prevalence was 44% [8]. Our review includes all women, but the other review and analysis included only high-school female students.

The result of this review pooled prevalence is higher than a nationwide study conducted in Ethiopia showed 30% [21]. This study also revealed higher finding than a meta-analysis among women in Ethiopian, which showed 46.93% [24]. This variation may be due to the study period.

This review also identifies several interconnected factors that can increase a woman’s vulnerability to violence. Women who received monthly pocket money from their parents were increased the odds of GBV. This association could be explained by the fact that financial dependence on parents can limit a woman’s autonomy and ability to leave a potentially abusive situation.

The odds of having GBV among women who have experience of sexual intercourse were higher than who have no experience of sexual intercourse. This finding was consistent with a study finding done in Ethiopia among high school students. This association is deeply rooted in patriarchal norms and power dynamics surrounding women’s sexuality. For some perpetrators, a woman’s sexual activity, especially outside of marriage or without their control, can be seen as a transgression warranting punishment through violence.

The increased odds of experiencing GBV were associated with being young in age. The possible explanation for this association could be younger women often have less social and economic power compared to older women. They may be more dependent on others, have fewer resources to escape abusive situations, and may be targeted due to their perceived vulnerability and lack of experience in navigating relationships.

The pooled odds of experiencing gender-based violence among women who consume alcohol were higher than women who never consume alcohol. Other study also reveals similar findings. The reason for this could be alcohol use can alter the level of mentation, impair judgment, reduce inhibitions, escalate conflicts, increases their willingness to take risks and makes less concerned by the consequences of their behavior.

Being single in marital status were increased the odds of GBV. The possible reason for this could be single women might be seen as more available or less protected, making them potentially more vulnerable to GBV.

And also, the odds of experiencing GBV were associated with tight family control. This could be true that families that exert excessive control over a woman’s movements, choices, and relationships can inadvertently increase her risk of GBV. This control can isolate women from external support networks, limit autonomy, and make it harder for to leave an abusive relationship or seek help.

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that the pooled prevalence of gender-based violence was significantly high. Women receive pocket money from their parents, lives in urban area, experience of sexual intercourse, being young age, consume alcohol, being single in marital status, tight family control and having multiple sexual partners were found to be associated with gender-based violence. The national governments and the concerned stakeholders should develop and implement multipronged interventions to address gender-based violence against women and to reach the Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs) target of 2030.

This systematic review and meta-analysis have several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, significant heterogeneity was observed across the prevalence studies, which may affect the precision of the pooled estimates. While we attempted to explore sources of heterogeneity through subgroup analysis and meta-regression, the limited number of studies for certain subgroups constrained these analyses. Secondly, the assessment of associated factors relied heavily on observational studies, which cannot establish causality. Finally, variations in the definition and measurement of GBV and associated factors across the primary studies may have introduced some degree of heterogeneity in the synthesis of these factors. Despite these limitations, this review provides a valuable synthesis of the available evidence on GBV and its associated factors among women in Ethiopia, highlighting the urgent need for continued research and targeted interventions.

All relevant data generated and analyzed in the analysis process is included in this article.

The authors would like to thank the authors of the included primary studies, which were used as a source of information to conduct this systematic review and meta-analysis.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Yirdaw, B.W., Yimer, B.B. Gender-based violence and associated factors among women in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Women's Health 25, 312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-025-03867-0