Human Resources for Health volume 23, Article number: 28 (2025) Cite this article

The COVID-19 pandemic posed unprecedented challenges for frontline healthcare professionals (HCPs), leading to high rates of burnout and decreased work motivation. Limited ability to provide adequate end-of-life (EOL) care caused moral distress and ethical dilemmas. However, factors that prevent burnout, reduce intent to leave, and enhance professional fulfillment remain underexplored. This study aimed to explore HCPs’ perceptions of work motivation during the pandemic, seeking insights to support their continued dedication.

A qualitative descriptive study was conducted through online semi-structured interviews (from August to December 2021) with HCPs who provided EOL care, working at intensive care units, specialized COVID-19 wards, and general wards across Japan. Aiming for a diverse sample in terms of gender, occupation, hospital size, and location, interviewees were recruited via the network of the Department of Health Informatics, School of Public Health, Kyoto University. Inductive thematic analysis was applied to interpret the data semantically.

The study participants were 33 HCPs (15 physicians and 18 nurses) from 13 prefectures. The following four main themes with 13 categories were revealed: Developing proficiency in COVID-19 EOL care through HCP experiences, Unity as a multidisciplinary COVID-19 team, Managerial personnel who understand and support staff in fluctuating work, and Social voices from outside of hospitals. These themes uncovered possibilities beyond the personal traits of HCPs and influenced their motivation by incorporating factors associated with healthcare teams, organizations, and wider societal contexts.

In this study, four themes, including the importance of organizational management to prevent isolation, maintaining connections among colleagues, and the need for supportive social voices from outside the hospital, emerged from interviews regarding HCPs’ work motivation during the pandemic. These findings highlight the complex interplay of individual, organizational, and societal factors in shaping HCPs’ motivation during pandemic waves.

World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency of international concern due to the global COVID-19 pandemic on 30 January 2020 [1]. From July to October 2021, during Japan's fifth pandemic wave, the appearance of the Delta wave caused a sharp rise in new positive cases and severe infections compared with the previous four waves [2]. Healthcare professionals (HCPs) experienced exhaustion from fear and helplessness about potential infection, unfamiliar practices such as overwork, psychological distress, and disconnection from management personnel [3, 4]. These conditions led to a high prevalence of fatigue, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and burnout [3, 5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], as well as decreased work motivation [14, 16, 17].

Unfortunately, a substantial number of these patients faced end-of-life (EOL) situations. Providing opportunities for HCPs to deliver adequate EOL care is essential for maintaining work motivation and job satisfaction [18]. However, HCPs were seriously challenged to provide adequate EOL care to terminal patients with COVID-19 during the pandemic [19, 20]. HCPs providing EOL care faced increased workloads and limited opportunities for human interaction, making it difficult to establish meaningful connections with patients [21, 22]. They struggled to reconcile their moral convictions with the constraints imposed by pandemic-related restrictions, leading to experiences of moral distress [23,24,25,26].

In our Providing End-of-Life Care for COVID-19 Patients (PRECA-C) Project [27], we found that strongly motivated HCPs committed themselves to providing remarkable EOL care. It remains unclear why participants in the PRECA-C Project were able to maintain work motivation in a high-risk environment despite the constraints imposed by the pandemic. Work motivation is defined as “a set of energetic forces that originate both within and beyond an individual’s being to initiate work-related behavior and to determine its form, direction, intensity, and duration” [28]. A deeper understanding of HCPs’ motivation in crisis EOL care may clarify this phenomenon's diversity and nuances. However, research on support interventions for HCPs is insufficient both quantitatively and qualitatively [29].

This study aims to explore how HCPs providing EOL care for COVID-19 patients in Japan sustained their work motivation during such demanding times. By examining the specific motivations and coping mechanisms of these HCPs, the research seeks to provide deeper insights into the diversity and nuances of maintaining work motivation under crisis conditions. The findings could contribute to a better understanding of how to support HCP well-being and develop effective strategies for future pandemics.

We conducted a qualitative descriptive study, a method often chosen when seeking a clear description of a phenomenon to focus on the perceptions of HCPs regarding their work motivation in providing EOL care for patients with COVID-19 [30, 31]. This study used in-depth online interviews to explore HCPs’ experiences and the significance of continuing their work from their perspectives and was conducted as one of the main subjects of the PRECA-C Project [28, 32]. The findings were reported following the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines [33]. The validity of the data interpretation was discussed with the research team and triangulation was conducted (Supplemental 1) [34].

This study was conducted from March 2020 to December 2021 in Japan. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) HCPs working in ICU, specialized COVID-19 wards, or general wards in Japan; and (b) HCPs who had experience providing EOL care for patients with COVID-19. In Japan, HCPs who were routinely involved in EOL care are also typically responsible for providing general care. Therefore, in this study, we did not place restrictions on the proportion of effort allocated to each type of care. HCPs predisposed to mental health issues or anticipated distress were excluded to avoid causing psychological distress by prompting the recollection of distressing experiences during interviews. The mail listserv of the Department of Health Informatics, School of Public Health, Kyoto University, which includes graduate students and alumni, was utilized to obtain referrals for HCPs with experience in EOL care. An email with a link to a website explaining the study was sent to potential participants, who indicated their intention to participate by clicking an icon, after which researchers followed up via email. We used purposive sampling based on profession, gender, hospital size, and participant age [35]. We stopped sampling when no new codes or categories emerged from the interviews as we reached data saturation.

We conducted one-on-one semi-structured online interviews via the Zoom online platform (Zoom Video Communications Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Interviews included privacy-related issues, with most pairs meeting for the first time to reduce bias, except for three pairs. While online interviews often lack nonverbal communication, Zoom enables visualizing and responding to nonverbal cues, aiding rapport building [36]. Three interviewers (MS, Female, RSN, MHS; MN, Female, OTR, DrPH; and MT, Female, MD, PhD) received guidance from a senior researcher skilled in qualitative research, particularly in EOL topics (HM, Female, academic researcher, PhD) before conducting the interviews. In this study, efforts were made to ensure that participants could express themselves in their own words as much as possible. A pilot study with two clinicians (AK, male, MD, DrPH; HI, male, MD, MPH) led to revisions of the interview guide. Two key questions were asked: “What kind of EOL care did you provide to dying COVID-19 patients and their families?” and “How did you feel as a medical professional after experiencing the EOL care of COVID-19 patients?” (Supplemental 2). All interviews were conducted in Japanese. Field notes were created during or immediately after the interviews.

As no suitable theories for burnout, stress coping, or work motivation were available, we conducted an inductive thematic analysis with a semantic focus on work motivation [31]. The recorded data was anonymized, and verbatim transcripts were created from the audio recordings. To analyze motivations for work related to EOL care, two independent researchers (MS and HM) thoroughly reviewed the data from various perspectives, generated codes, and discussed them to reach consensus as peer debriefing. Similar codes were grouped, and properties and dimensions were summarized in a matrix during the analysis process to organize data segments hierarchically and facilitate conceptualization (MS) [37]. The themes that facilitated conceptualization were then discussed, and consensus was formed (MS and HM). For sections where consensus could not be achieved, discussions were held along with a supervisor to aim for agreement (MS, HM, TN, MD, PhD). An independent researcher (HI) not involved in the verbatim transcription conducted an audit trail between data segments and subthemes. For the final consensus on data interpretation, discussions were held within the PRECA-C team, comprising two clinicians (AK and HI) caring for patients with COVID-19. NVivo 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd., Burlington, MA, USA) was utilized to manage the verbatim transcript data. No verbatim transcripts or feedback regarding the results of the analysis were provided to the participants.

All participants read the online research interface explaining the study objectives, voluntary participation, no disadvantages for refusal, and the option to withdraw consent at any time. Before the interviews, we ensured that the environment provided adequate privacy, obtained consent for video recording, and verbally reaffirmed the participants'consent. The data was anonymized and stored in a secure university cloud. After the transcription, the audio and video files were deleted to ensure data confidentiality. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University (IRB No. R3027).

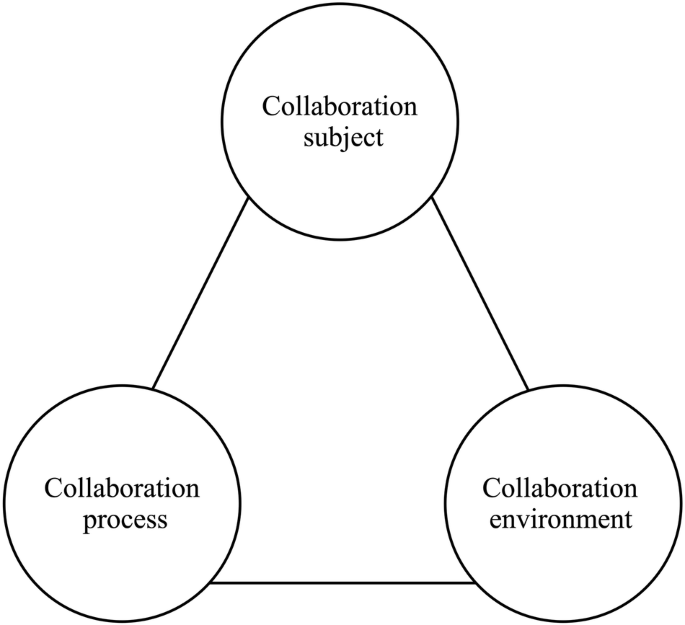

A total of 33 individuals, including one participant who underwent two interviews, were included in the analysis. Among those registered, contact could not be established with three individuals, and one person was excluded due to scheduling conflicts. The participants were from 13 of Japan’s 47 prefectures and consisted of 15 physicians (medical doctor: MD) and 18 nurses (NS), with the majority being HCPs in their 30 s (Table 1). They provided EOL care to an average of 4.8 patients (standard deviation [SD]: 3.8 patients) and conducted interviews that lasted an average of 50 min (SD: 10.6 min). The analysis revealed 13 categories regarding perceptions of work motivation. Focusing on the individual HCPs and progressively encapsulating the environment and organizational dimensions, four themes emerged: Developing proficiency in EOL care for patients with COVID-19, Unity as a multidisciplinary COVID-19 team, Managerial personnel who understand and support staff in fluctuating work, and Social voices from outside of hospitals (Table 2).

Throughout the recurring pandemic, HCPs endured physically and mentally demanding circumstances. Despite this, they felt a profound sense of duty within their respective roles, striving daily to provide EOL care to their patients through trial and error based on their accumulated experiences. They found meaning in the unique circumstances of the pandemic by deriving significance from the provision of successful care and taking advantage of the opportunity for professional growth as specialized practitioners.

During the fifth pandemic wave, while facing the possibility of contracting the infection themselves, HCPs continued to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) and exert efforts in zone-restricted areas (ID: 2, 5, 11, 22, 33). However, when active treatment proved ineffective and EOL care became a priority, HCPs faced a dilemma between maintaining infection control and providing appropriate EOL care, which required them to navigate trial and error in delivering EOL care on the ground. They were restricting visits to prevent infections, yet they also wanted to facilitate precious time for patients and their families to be together (ID: 2–4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 15–18, 22, 26, 28–33). While online visitation tools were implemented, communicating the patient’s condition and providing decision support via the telephone was exceedingly challenging, especially for elderly or device-lacking families (ID: 1–4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 14, 32, 33). Particularly distressing was the reality that many patients passed away and were cremated without their families getting to see them face-to-face (ID: 1–4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 14, 18, 24–27, 29, 31–33).

“We ask families to wear PPE and talk to their loved ones from a few meters away without entering the room.” (ID1, MD, Male)

Despite restrictions, HCPs continuously sought methods to facilitate family visits. In the fifth wave, they not only prioritized tablet-based interactions but also strived for face-to-face connections between patients and families whenever possible. HCPs expressed a desire to facilitate EOL care that would allow for the viewing of the deceased’s face after death, even if only for a short time. Striving to provide EOL care that resembled normal times contributed to professional satisfaction and boosted motivation (ID: 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 19–21, 26, 28, 30, 31, 33).

“It’s through FaceTime, but as part of caring for the family. By doing what we could, being able to let families see each other, you could say it brought them some joy.” (ID: 4, NS, Female)

Amidst experiencing the fifth wave of the pandemic, both physicians and nurses adopted techniques similar to those in normal times, such as the use of PPE and timing of EOL treatments, even in COVID-19 care (ID: 4–6, 8–10, 15). During the fifth wave, they were also supported by experiences from previous waves (ID: 5, 8–10). The term “getting used to” was frequently used. Younger HCPs expressed a desire for COVID-19 ward duty as an opportunity to expand their own experiences and enhance their skills (ID: 4, 12, 15, 24, 32). Moreover, senior HCPs in mentoring roles saw the chance to cultivate younger HCPs by showcasing their expertise and engaging with patients, believing that they had more opportunities to mentor than in normal times (ID: 8, 10).

“There are plenty of opportunities to teach things like respiratory physiology at the bedside, so in a way, it brings me great joy. I think it’s a chance to teach.” (ID: 10, MD, Male)

In specialized COVID-19 wards, communication difficulties among staff members, in addition to with patients, often impacted staff work motivation. To enhance EOL care, the significance of team cohesion, discussions during meetings, and interdisciplinary collaboration were emphasized. Notably, the importance of interprofessional discussions, not only within the same profession but also across various disciplines, including physical therapy, pharmacy, nutrition, clinical engineering, social work, and administrative staff, was highlighted. In addition, the significance of staff communication and interaction during break times and informal settings was emphasized.

Due to the pandemic waves, a new ward that necessitated strict adherence to the WHO’s recommendation to avoid the “Three Cs (Crowded places, Close-contact settings, and Confined and enclosed spaces)” [38], both within and outside the hospital premises, was established. Consequently, silent meals were enforced during lunch breaks, depriving staff of opportunities to acquaint themselves with newcomers (ID: 21). Those in positions responsible for training junior physicians were unable to provide adequate support, leading to the resignation of novice doctors (ID: 21). Nurses were concerned about potential communication errors due to a lack of understanding about the career and experiences of their team members (ID: 4, 6, 15, 20, 21).

“Lunch breaks are partitioned off... I feel like we missed out on getting to know them better and didn't engage with them much.” (ID:21, MD, Female)

During the fifth wave, the importance of meetings in the COVID-19 ward was underscored. These meetings covered treatment strategies, ethics, and postmortem care (ID: 6, 10, 14, 15, 17, 19, 21, 26, 27, 29, 32, 33) and involved professionals from various disciplines, such as physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, palliative care teams, hospital ethics committees, social workers, and administrators (ID: 10, 14, 15, 21, 27, 32). These sessions served as platforms for not only information-sharing and policy decisions, but also the detailed exchange of care-related information. They also provided a space for nurses constantly engaged in EOL care at the bedside to express their emotions, alleviating the burden of moral distress associated with treatment decisions for physicians (ID: 6, 19, 26, 29).

“I feel like I was able to face the patient’s pain well… We reflected on this with the senior nurse. I was really saved by that. I hadn’t been able to stop crying until then.” (ID: 6, NS, Female)

Nurses in the COVID-19 ward comprised volunteers and staff from both within and outside the hospital, while physicians came from various departments. Silence during breaks limited opportunities for HCPs to get to know each other (ID: 21). However, diverse forms of communication respecting staff feelings, whether work-related or not, fostered a sense of contentment in the workplace. This contributed to a new atmosphere across the ward, enhancing team cohesion and subsequently boosting individual work motivation. Additionally, this conducive atmosphere facilitated collaboration, making cooperation easier and enhancing work motivation (ID: 11, 12, 14–16, 20, 22, 28, 31, 32).

“Fortunately, all the staff members are kind and are always smiling and talking with each other. I think that’s a relief...” (ID: 22, NS, Male)

During a pandemic, changes in the healthcare system result in shifts in the operations of HCPs. Some HCPs experienced workload imbalances due to the evolving infection situation, leading to feelings of being overwhelmed. Tailored allowances for the duties performed by HCPs, alongside the presence of specialized nurses who transcended ward or departmental constraints, and direct supervisors involved in management, all contributed to supporting the work motivation of HCPs.

During the pandemic, physicians found themselves rotating between busy and less busy departments (ID: 23), while nurses juggled between working in ICUs or specialized COVID-19 wards (ID: 26, 29–31) and offering assistance to other units, resembling temporary or casual labor, once the pandemic subsided (ID: 1, 23, 26, 31, 32). Physicians noticed the challenging workload of nurses and were concerned that it might lead to a decrease in the nurses’ work motivation (ID: 1, 5, 9, 12, 23, 30).

“While COVID patients were there, nurses did critical and EOL care. But they get shuffled to other wards when there's no COVID around… that's pretty tough.” (ID: 1, MD, Male)

Direct supervisors participating in clinical care and engaging in communication fostered a sense of understanding among HCPs. Consequently, this heightened their desire to contribute to the workplace where the supervisors were present, elevating their work motivation (ID: 6, 10, 12, 20, 21, 29).

“My supervisor is kind and often checks in with me. When I see such openness, it makes me feel like I want to contribute a bit more to the workplace and return there soon.” (ID: 21, MD, Female)

The hospital administration recognized the physically and psychologically demanding nature of EOL care amidst the pandemic, and the establishment of systems for such care was instrumental in bolstering the work motivation of frontline HCPs. For instance, the provision of accommodation (ID: 14, 29), holiday entitlements, and fair remuneration (ID: 5, 11, 17), as well as mental health support and educational programs facilitated by specialized nurses (ID: 4, 11, 18, 19, 30), were in place.

“I felt reassured when the infection control nurse said, ‘It’s okay if you don’t touch that area’. It didn’t seem like they had a negative view of postmortem care” (ID: 18, NS, Female)

The continuous media coverage of COVID-19 depicted both positive and negative aspects, shaping the narratives surrounding the situation. The negative aspects often led to societal prejudices and threatened the personal lives of HCPs. The deployment of external support staff contributed to mental resilience by ensuring rest periods for primary staff. Furthermore, enabling interactions outside work duties provided HCPs with opportunities for cognitive rejuvenation.

Throughout the fifth wave, the media extensively covered the pandemic, significantly impacting the frontline HCPs (ID: 2–5, 7, 9, 19, 29, 30, 32). Some media coverage perpetuated biases, such as suggesting that HCPs in COVID-19 care settings were carriers of the virus (ID: 1, 2, 9, 20, 29), thereby affecting HCPs’ personal lives. Consequently, HCPs perceived substantial constraints on their personal lives (ID: 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 24, 25). In contrast to such stigmatizing coverage, HCPs were encouraged by the supportive messages from the media across the country (ID: 30). They wished for more media coverage of the harsh reality of patients suffering and dying alone due to COVID-19 (ID: 4, 27, 30, 32).

“People are frustrated, but others are suffering and dying. The media needs to show what’s really happening in hospitals. Some even say COVID is a hoax… Hearing'It’s just a cold'made me so angry. Could you say that to someone who's dying?" (ID32, NS, Male)

The influence of the media was not entirely negative. In the context of particularly challenging EOL care, some HCPs found a sense of achievement in receiving positive feedback about their care from families, even though obtaining feedback from bereaved families through the media was challenging (ID: 20, 27, 30, 31).

“Families sharing their experiences through ICU diaries on social media was heartwarming. Other staff members felt reassured that the care they provided was meaningful and impactful.” (ID: 20, NS, Female)

HCPs were expected to adhere strictly to infection prevention measures, which resulted in constraints such as being unable to dine out or attend weddings. These limitations led to a sense of dissatisfaction among HCPs compared with non-medical professionals (ID: 2, 4, 9, 11, 12, 20, 24). Conversely, in their personal lives, the presence and support of colleagues, family, or partners made them feel needed and supported, thereby fostering motivation in their work (ID: 1, 8–11, 14, 15, 24, 25, 29).

“I'm enjoying myself. My family’s supportive. I switch off from work when I’m at home.” (ID24, MD. Male)

During the pandemic, human resources were insufficient, leading to exhaustion among HCPs. Amid the pressures of 24-h COVID-19 care and management, the temporary acceptance of external personnel into the hospital provided brief moments of respite, contributing to the mental well-being of HCPs (ID: 5, 23, 30, 31).

“It was hard to stay motivated when patients didn’t survive, but having support for critical care and guaranteed days off brought a sense of mental relief.” (ID5 MD, Male)

In this study, we interviewed HCPs experienced in EOL care who encountered challenges during the fifth COVID-19 pandemic wave in Japan. As a result, we identified four themes: Developing proficiency in EOL care for patients with COVID-19, Unity as a multidisciplinary COVID-19 team, Managerial personnel who understand and support staff in fluctuating work, and Social voices from outside of hospitals. These themes extended beyond individual HCP characteristics, highlighting factors related to healthcare teams, organizations, and societal contexts that contributed to work motivation in challenging situations. This led to three significant implications for continuing work amidst pandemic waves.

At the team level, multidisciplinary discussions within the COVID-19 team enhanced professional satisfaction by leveraging skills from past pandemics. Regular open discussions strengthened HCPs'sense of achievement and team cohesion, covering topics like EOL care, postmortem care, and treatment decisions. As needed, discussions helped to reduce the moral distress of HCPs [43]. The alleviation of moral distress has been shown to prevent burnout [44,45,46]. Discussions during meetings fostered affirmative feelings among HCPs toward patient care, promoting work motivation. This provides opportunities for HCPs to express feelings of remorse due to the inability to be present beside dying patients under contact restrictions, potentially reducing moral distress, which is also a novel finding. The establishment of daily meetings focusing on EOL care, including postmortem discussions, emerged as a significant opportunity within teams to enhance work motivation among HCPs. The environment conducive to building positive relationships with young professionals, viewing the pandemic as an opportunity for professional growth, was a novel finding in terms of work motivation. Respectful, interdisciplinary communication fosters workplace communities, thereby enhancing team cohesion [39,40,41,42]. By fostering meticulous communication, individuals can share a sense of interpersonal safety with other members of the workplace, thus maintaining psychological safety as a collective norm [47]. Thus, diverse meetings contributed to fostering a workplace culture focused on communication, supporting the cultural development of the new team.

At the hospital level, recognizing the pivotal role of direct management at hospitals, structural reforms were initiated to create a more supportive work environment for frontline HCPs. During the pandemic, HCPs faced demanding conditions and sought increased organizational support [48]. Previous pandemic studies have demonstrated that by recognizing and valuing the efforts of HCPs, organizations can promote the continuation of their strenuous work [39,40,41,42]. However, this study emphasizes the importance of fostering workplace culture through casual communication and further highlights the key role of understanding and cooperative direct supervisors in this process. For example, communication from direct supervisors enhances individual staff members'self-esteem and ensures a safe workplace environment. Even during work duties, simple communication among staff and direct supervisors'individual care contributes to boosting HCPs’ self-esteem and maintaining a supportive workplace atmosphere and safe environment [49]. Moreover, external staffing and workload management, including ensuring rest and flexible arrangements, can help prevent turnover and create a reassuring work environment [17, 49]. This approach relieves physicians from life-and-death decisions and provides nurses with a sense of release in their work environment, regardless of pandemic waves [50]. Prioritizing the availability of skilled personnel to respond to the pandemic is essential.

At the societal level, social influences outside the hospital had both positive and negative effects on HCPs'motivation. For instance, the inability of patients and families to meet face-to-face caused moral distress for both HCPs and families [51]. Despite providing demanding care, such as ICU diaries, evaluations from patients and families in the medical settings were rare, leading HCPs to feel a sense of inadequacy and making it difficult for them to connect with work motivation. However, feedback on EOL care from patients and families through social media and mass media significantly alleviated HCPs'moral distress, thus enhancing their work motivation. Additionally, as reported in general COVID-19 care, HCPs found emotional support and relief through personal connections with friends, family, and intimate partners, as well as through support from individuals outside the healthcare environment during the pandemic [52,53,54]. However, excessive media coverage often imposed societal pressure on HCPs to remain unwaveringly dedicated to their duties, resulting in psychological burdens. Social pressure sometimes accompanied stigma [55], which could make HCPs feel suffocated and negatively impact their work motivation. HCPs have been reported to feel misunderstood and unappreciated by society, employers, patients and their families, as well as their own friends and family, which can lead to feelings of sadness, anger, and frustration [56]. HCPs preferred news coverage that reported the reality of EOL care for patients with COVID-19 in clinical settings, rather than focusing on negative portrayals of their private lives. Environmental factors such as social pressure can either support or undermine individual work motivation. Therefore, it is imperative to accumulate further insights into HCPs’ experiences and engage in discussions with the public and media stakeholders.

This study has some limitations. First, the participants were recruited from HCPs who had not resigned at the time of the survey, meaning HCPs who had resigned could not be included, leaving it unclear whether similar perspectives would be found among those who had left. This study did not aim to specifically address work motivation in relation to COVID-19 EOL care and general care separately. HCPs who experienced stigma or those who had resigned could not have been included in this study but may have had potentially different work motivations, which may not have been fully captured. Second, since the survey was conducted during Japan’s fifth pandemic wave, the experiences examined might be specific to that time and situation. Additionally, while the study focuses on Japanese HCPs, perspectives from other countries could offer valuable insights for sustaining HCPs’ work motivation in future pandemics. Third, six of the seven authors are HCPs, which may have led to some bias in interpreting the data with empathy for frontline workers. However, the diverse backgrounds of the authors, including physicians, nurses, occupational therapists, and epidemiologists, helped ensure reflexivity during the analysis. Fourth, it did not provide in-depth theoretical interpretations, because qualitative descriptive studies aim to present phenomena as they are. The four identified themes can still offer valuable support for the motivation and well-being of HCPs providing EOL care during pandemics.

Four themes emerged from interviews regarding HCPs’ perceptions of work motivation during the pandemic. Hospital administrators should manage their organizations to prevent HCP isolation and ensure they maintain colleague connections. Furthermore, it is worth noting the social voices from outside the hospital encouraged the HCPs. These findings highlight the intricate interplay of individual, organizational, and societal factors in shaping the work motivation of HCPs during pandemic waves.

The findings of this study are attributed to Kyoto University. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

- PRECA-C Project:

-

Providing end-of-life care for COVID-19 patients project

- HCP:

-

Healthcare professional

- PPE:

-

Personal protective equipment

- EOL:

-

End-of-life

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- MD:

-

Medical doctor

- NS:

-

Nurse

The authors express their sincere appreciation to all participants who provided EOL care on the front lines to patients with COVID-19.

This study was funded by the Kyoto University research grant, the Data-oriented Area Studies Unit (DASU) Research Units for Exploring Future Horizons Phase II, and Kyoto University Research Coordination Alliance.

All participants were required to read the online research participation interface that explained the study objectives, the voluntary nature of participation without any disadvantages for refusal, and the ability to withdraw consent at any time. Subsequently, the participants provided online consent by clicking the icon. Before commencing the interviews, consent was verbally reaffirmed. The data were anonymized and stored in a secure university cloud. After the transcription, the audio and video files were deleted to ensure data confidentiality. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University (IRB No. R3027).

Participants provided consent for the publication of this study.

All authors completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf. The authors declare that they have no competing interests expecting one author below.

To ensure the privacy of interviewees, no data are available.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Sano, M., Mori, H., Kuriyama, A. et al. Exploring perceptions of work motivation through the experiences of healthcare professionals who provided end-of-life care during the COVID-19 pandemic (PRECA-C project): a qualitative study. Hum Resour Health 23, 28 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-025-00997-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-025-00997-2