Deadly Weather May Come With No Warning - The Atlantic

This is why the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Weather Service (NWS) are so crucial for the nation’s emergency-response system. These agencies’ scientists gather and interpret meteorological data, identifying the patterns that should trigger a warning about a dangerous weather event. If we didn’t have that capacity, then we wouldn’t get the warning, and we wouldn’t have time to prepare.

Providing tornado notifications is one of these agencies’ most important tasks. The hierarchy of these alerts—watch, warning, emergency—is not an advisory about a tornado’s intensity but one about its likelihood and imminence. It’s all about time: A tornado watch means, in effect, that you may want to start to get ready if something bad happens; a warning means prepare for imminent danger because tornadoes have been identified in your area; the emergency declaration, though rare, means that you have no more time, and should take cover immediately.

Preparing for emergencies is always difficult; extreme climate events can overwhelm even the best-laid plans. But this challenge has been exacerbated by major staffing cuts imposed by Elon Musk’s and President Donald Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency. Today, about 40 percent of the 122 local forecasting offices of the NWS have significant staffing gaps. More than 10 percent of its 4,800 employees have left in recent months—either dismissed, retired, or bought out. Some of the usual predictive measures, such as the deployment of weather balloons and Doppler radar, many of whose experts and technicians have been fired or laid off, are now not available.

DOGE’s full impact on the nation’s disaster preparedness remains to be seen, but with hurricane season beginning on June 1, many observers are warning of fallout from serious staff shortages. Whether DOGE cuts affected tornado alerts this past weekend is as yet impossible to determine. Anecdotal accounts tell of heroic efforts to staff up an NWS office in Kentucky to compensate for shortages ahead of this storm system. Governor Andy Beshear said he didn’t “see any evidence” that the cuts had affected warnings to the state’s population on this occasion.

David Michaels and Gregory Wagner: DOGE is bringing back a deadly disease

Problems of staffing, capacity, and cuts demand more study as we enter another season of extreme weather. But what we already know is this: When we face the risk of a mass-casualty disaster, time is our most precious commodity. In this age, unfortunately, we can expect mayhem from all sorts of sources: cyberattacks, terrorism, active shooters, weather events, overburdened aviation systems, deadly viruses. A nation best prepares for a crisis not by ignoring it and hoping it never happens, but by anticipating it and planning for it. The success of such preparation is measured by the ability to provide more time, because more time means that those affected will have better options.

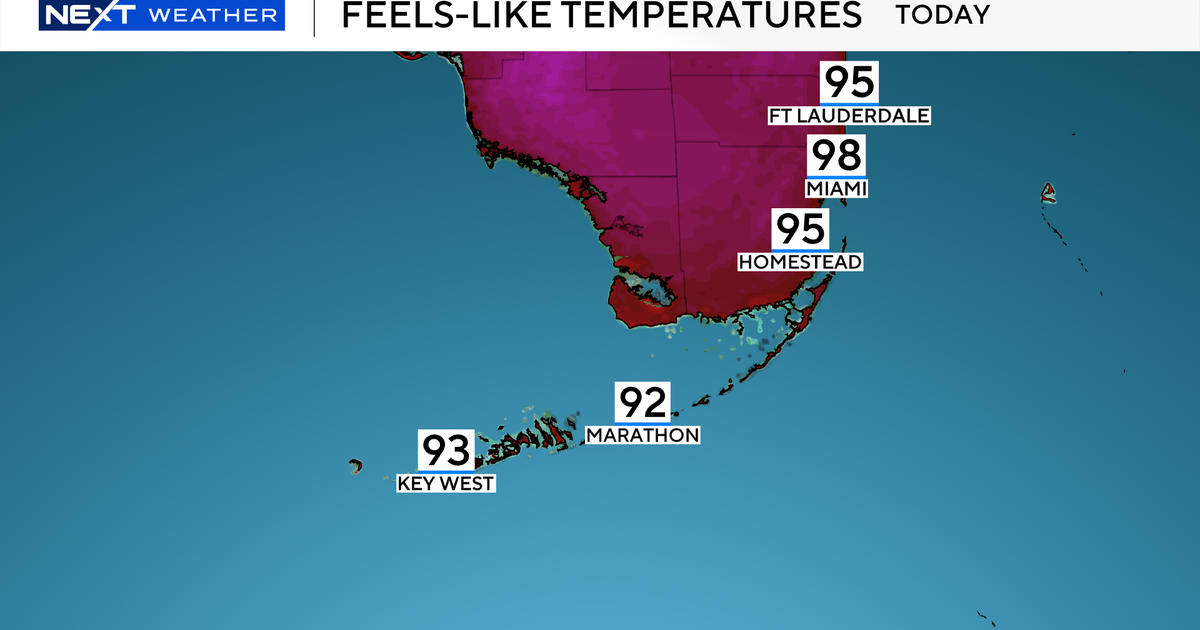

The scientists at NWS and NOAA are in this time-management business. Their job is to measure how changes in the temperature of the air or the ocean interact with wind speed, and to recognize the patterns that signal potential danger—all to give first responders and communities more time to get ready for powerful storms, possible flash floods, damaging winds. That not only gives first responders the ability to know how and where to deploy resources; it also enables citizens to protect themselves, their family, and their property. This is where the precision of the alert matters, because it guides lifesaving decisions made by thousands, sometimes millions, of people: Should they evacuate before a hurricane? Is there time to board up the windows? Should they run to a shelter?

Some of the most consequential recent changes to emergency management have been in this crucial capacity to buy more time. New technology, including user-friendly apps that people can download to their phone, provides the public with better situational awareness. During the Los Angeles fires earlier this year, a nonprofit named Watch Duty, whose employees include dispatchers, volunteers tracking radio reports, and both active and retired firefighters, distributed real-time information about where fires were raging so that citizens would know how much time they had before they were in immediate danger. Earthquakes were once viewed as leaving populations wholly vulnerable, but new early-warning systems can get data from ground-monitoring devices and provide a loud alert before the seismic activity intensifies. For people who live in high-risk geological zones, a few extra seconds could save lives. The MyShake app, an initiative from UC Berkeley, aggregates this seismic information and crowdsourced data with an individual user’s phone location to target precise alerts.

Meanwhile, NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory has been investigating how people react to the time notification and implied deadline in an alert, and what the government can do to communicate more effectively about imminent risk. Last summer, I met a social scientist named Makenzie Krocak in Norman, Oklahoma, after the 2024 tornado season for the filming of a documentary. Her work linked up with disaster-management efforts because she was studying how timely information needs to “meet people where they are” so that they can get its full benefit.

These tech innovations and the NOAA project point to an essential fact: The private sector always has a part to play, but it cannot pick up the slack created by DOGE’s indiscriminate cuts, because these new developments still depend on data from government climate, seismic, and atmospheric programs. The dismantling of our nation’s early-alert and notification system is a dangerous gamble that is already affecting America’s citizens. Ultimately, this loss of capacity deprives us of vital time to seek safety from a catastrophic weather event that may be only seconds away.