Current status of school vision screening--rationale, models, impact and challenges: a review

Current status of school vision screening—rationale, models, impact and challenges: a review

Uncorrected refractive error is the leading cause of vision impairment in children globally, and studies have demonstrated that spectacle correction addresses the large majority of childhood vision impairment. Furthermore, trial evidence illustrates the beneficial impact of spectacles on learning, with effect sizes exceeding that of other school health interventions. While it is established that good vision is important for learning and optimising childhood development and quality of life, many countries lack healthcare systems that provide vision screening or universal access to eyecare for all citizens. This review examined school vision screening across several regions/countries, focusing on conditions that should be targeted and the corresponding interventions. The range of international models, the status of global refractive service coverage and measures needed for improvement are discussed. Vision screening protocols need to effectively detect vision impairment, seamlessly connect with intervention services to deliver spectacles and signpost for future access to eyecare. Conditions which may not be treatable with spectacles alone, including amblyopia, strabismus and other ocular diseases, also warrant signposting for treatment. The vision community must unite to urge governments to invest in building service capacity; allocating the necessary resources and effectively developing public health systems to support vision screening and access to eyecare. Schools play a crucial role in enabling population-based vision screening and need to be supported with eyecare interventions and resources. This will ensure optimised approaches to correct avoidable vision loss and provide children with the educational and health outcomes they deserve.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

As with any healthcare service, it is reasonable to ask: why should schools assume responsibility for vision screening? By 2020, nearly every country in the world offered some form of school-based or school-linked health service to improve the physical health and nutritional status of school-going students, including school meals, vaccines, integrated health curriculum, oral screening, among other interventions.1 Pandemic-related school closures in early 2020 resulted in the greatest education crisis in history and simultaneously resulted in 370 million children going without food due to the loss of school meals alongside well-established delivery of simply public health services to schoolchildren. The recent COVID-19 pandemic illustrated exactly how dependent the world has become on schools to deliver services beyond the academic realm.2

A recent review examining the role of schools and vision care summarised that ‘schools are not restaurants, but they must and do help to feed a substantial number of the world’s children. Schools are not hospitals, but they are increasingly and unavoidably pressed into the role of safeguarding children’s health’.3 However, while vaccination and nutritional support have the potential to prevent death, delivery of vision services does not, at least not directly. Is the growing trend of using schools4 as a platform for vision care simply an instance of asking schools to be all things to all people?

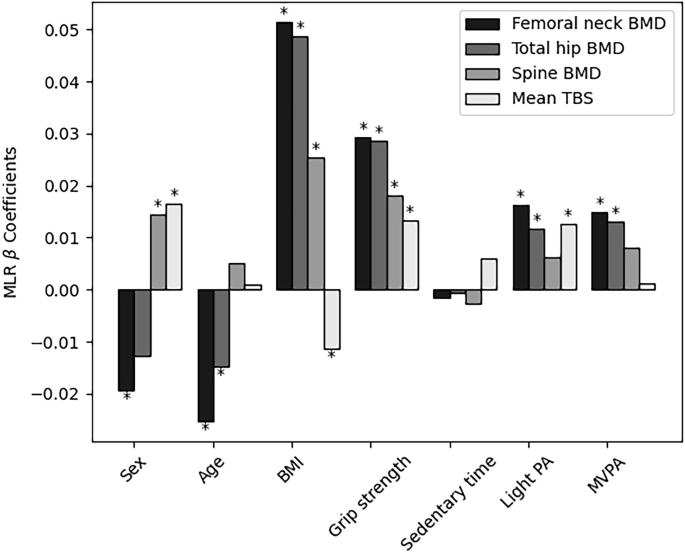

There are several compelling reasons to believe that delivering vision care through schools benefits both the child and the learning environment. The first is the causal connection between vision and learning. Ample trial evidence consistently shows the beneficial impact of glasses on educational outcomes (table 1).5–11 Effect sizes of spectacle corrections have generally exceeded those of other school-based health interventions, illustrating that improved vision through provision of spectacles has a substantive impact on learning.5

Table 1

Summary of findings (including RCT evidence) adapted from scoping review by Zhang et al 11 demonstrating that improved vision for children improves educational performance, aligned to SDG 4

Second, school screening and delivery of glasses is a cost-effective means of delivering on several of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG): particularly SDG 3, improving health and well-being; SDG 4, which focuses on access to quality education; and SDG 10, which focuses on reducing inequalities, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) and marginalised communities. Lester et al 12 reported the cost of eye examination per child was US$0.64, rising to US$12 with spectacle provision. Programmes employing screening and ready-made spectacles cost US$0.60 per child, thus affordable for scaling in low-resource settings in both Africa and Asia.13 Studies in Africa, Latin America and Asia show that spectacle correction addresses the large majority of childhood vision impairment.14–17 For this reason, the World Bank’s Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition, included school-based vision screening and provision of spectacles as part of its essential package for school-age children. This package was evaluated as (1) good value for money in multiple settings; (2) able to address a significant disease burden and (3) feasible to implement in a range of low-income and lower-middle-income countries, making it suitable for inclusion within an essential Universal Health Coverage package.18

The third argument for school-based vision services is the recent evidence linking children’s vision impairment to poor mental health, including depression and anxiety.19 The strongest evidence is for the association between myopia and mental health. When myopia is managed, children learn better, not just because they see better, but because learner physiological well-being has been improved in concrete, measurable ways.

Global efforts by the UNESCO and governments to boost school attendance have increased the efficiency and coverage of school vision programmes, and universal primary education was one of the most significant achievements of the Millennium Development goals. However, there is a complex relationship between school attendance, school hours and vision as early and intensive schooling is a major driver of myopia, the leading cause of vision loss in children worldwide.20 Hence, as more children attend school, the incidence of vision impairment and the need for screening will rise.20 While schools are the most effective setting to identify and correct common vision problems, community-based vision screening initiatives are also necessary to reach children with complex issues that prevent school attendance.

This review examined various aspects of school-based vision screening, including relevance of current targeted conditions, current interventions and their shortfalls, a variety of international models (online supplemental appendix 1), potential for combination with other conditions, status of global refractive service access and measures needed to improve the situation.

Uncorrected refractive error (myopia, hyperopia and astigmatism) is the leading cause of vision impairment in children globally.21 Spectacle correction is a readily available and inexpensive treatment. As summarised earlier, randomised trials have consistently shown that correcting refractive error with glasses improves children’s academic performance.5–10

Globally, myopia is increasing, and the burden is expected to grow in school-age populations.22 23 Evidence suggests that the recent COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated this trend.24 While glasses address the visual impairment from myopia, high myopia (beyond −6.00D) can be vision-threatening. There is growing interest in interventions to prevent or slow myopia progression.

Kulp et al 25 demonstrated that hyperopia is associated with lower reading ability and educational achievement and that many children who could benefit from spectacle correction do not have glasses. A recent systematic review26 established a link between the correction of hyperopia and improved learning outcomes, though trial data are lacking. Vision screening programmes typically measure monocular distance visual acuity, but this alone is a poor predictor of hyperopic or astigmatic refractive errors.27 28

Amblyopia and strabismus are inter-related conditions that significantly affect visual function in infants and young children. In the USA, their combined prevalence ranges from 1% to 6%,29 30 with amblyopia being the leading cause of uniocular vision impairment at 2–3%.31 Amblyopia is often linked to anisometropia, high refractive error and strabismus. Globally, the pooled prevalence of strabismus is 1.93%.32 Early intervention is crucial due to its impact on vision-related quality of life.33

Consideration should be given to post-screening follow-up as well. Vision screening has a 10–20% false-positive rate,34 and over half of children who fail vision screening do not go on to receive follow-up.35 Barriers such as lack of insurance and poor referral pathways limit access to follow-up care.36 School-based programmes can help increase follow-up rates by partnering with community organisations to provide eye exams and affordable/subsidised spectacle provision.37

While glasses and contact lenses improve vision, high myopia increases the risk of sight-threatening conditions like retinal detachment, myopic macular degeneration and choroidal neovascularisation.38 The rise in high myopia places a considerable economic burden on healthcare systems, with costs increasing with age.19 39 Preventive measures are crucial. A two-pronged approach should be adopted: lifestyle modifications to prevent or delay myopia onset in non-myopic children and treatments to prevent progression to high myopia in those affected through retardation of progression. Interventions focusing on modifying lifestyle factors,40–43 including encouraging outdoor activities and avoiding excessive near work demands,44 can reduce the risk of myopia development.

Evidence-based interventions such as atropine eye drops and optical devices, such as peripheral defocus myopia control spectacles and contact lenses, can also help reduce myopia progression.45 Myopia progresses faster in younger children and in the first few years after onset, so it is important to evaluate myopic young children for high myopia risk later in life and manage them appropriately. Some interventions have potential side effects.46 47 Atropine eye drops, especially at high dosages, can cause photophobia and reduced accommodation amplitude.48 49 Rebound effects after stopping atropine have also been reported.50 Orthokeratology lenses carry risks, including infectious keratitis.51 It is imperative to weigh potential benefits and risks to make informed decisions about suitable approaches.

Other emerging approaches include light therapy, with studies employing both blue and red light therapy to modify eye growth through exposure of the eyes to specific wavelengths of light.52 53 However, light therapy for myopia control is still a developing area, and longer-term studies and trials are needed to determine optimal treatment parameters and better understand safety, benefits and limitations.54

Table 2 provides a comparison of the different methods of implementation of school vision screening and evaluates the advantages and disadvantages.

Table 2

Comparison of the different methods of implementation of school vision screening with evaluation of advantages, disadvantages and opportunities

Barriers like travel distance, lack of perceived need, financial constraints and lack of time often lead to non-adherence with referral services.55 56 While school-based delivery of refractive services requires skilled human resources and faces logistical challenges delivering healthcare in a non-clinical setting, it can significantly reduce non-adherence.57–59 Referral to local vision centres may also have drawbacks, such as limited access to cycloplegic refraction.60 Even when refractive services are provided in schools, collaboration with local eyecare providers is essential for complex needs.60

Non-health personnel can effectively deliver vision screening to school children. Teachers often participate because they are familiar with students and parents.61 Sensitivity of teacher screeners varies from 25 to 94%,62 but specificity is generally high, crucial for efficient screening.63 64 Teachers also promote consistent classroom glasses wear,65 as demonstrated in a trial in China.66

A trial in Tanzania found children were more likely to wear glasses if provided free (31%) rather than if they had to purchase them (16%).67 While the facility for the purchase of spectacles can financially sustain programmes, this may not be permitted in some areas and can be logistically challenging. The PRICE trial in China showed that selling ‘upgrade’ glasses can succeed even when standard glasses are free.68

Ready-made glasses are widely used in low-resource settings. Modelling showed 51% of children could be corrected with ready-to-clip glasses using the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB) eligibility criteria.69 Trial evidence from India showed similar wear rates for ready-made (75.5%) and custom-made glasses (73.6%).70 Cost-minimisation analysis showed ready-made glasses have significant cost-saving potential.71 Studies of self-refraction show that vision of ≥6/7.5 in the better-seeing eye can be achieved in >90% of eligible children (astigmatism<0.75D).72 73 Earlier designs were unpopular,74 but recent studies suggest comparable wear rates between adjustable and standard glasses.75 Self-refraction can be accurate in children as young as 6 years old76 and is now used in non-governmental organisation (NGO) programmes in low-density areas like Mongolia.

In many LMICs, few children with disabilities attend inclusive schools, and many do not attend school at all. Consequently, they miss school screenings and lack potentially beneficial support.77 Vision and hearing screening programmes must reach out to children with disabilities at home, in the community or in specialised schools. Conventional vision testing may not identify children with complex disabilities.78 To counter this, medical professionals and educators should receive training in accessible vision screening tools and strategies. If an initial vision screening is ineffective, a referral is needed for further skilled assessment.

There is a high prevalence of vision and hearing impairment in children with complex disabilities, often undetected.79 80 Children with sensorineural hearing loss are more likely to have refractive errors and retinal abnormalities,81 with ophthalmic problems ranging from 40% to 60%.82 All children with disabilities should receive appropriate vision and hearing screening to connect them and their families to necessary services. Screening programmes are not uniformly implemented83 84 as protocols and practices are inconsistent84 and few include both hearing and vision screening.85 In a recent WHO publication by the Health Promoting Schools initiative, schools are recommended to provide more comprehensive health support to children and adolescents, including diet, physical activity, myopia and hearing screening, and lead exposure.86

Communication strategies in LMICs generally target two main groups: children and the community. Studies show that few strategies yield positive results. Zhang et al 87 conducted a randomised controlled trial in rural China to determine whether an eye health information campaign improved spectacle adherence. There were three arms: a control group with screening but no health education, one receiving health education only (targeting children, teachers and parents) and one with health education and subsidised spectacles. The combination of an information campaign and subsidised glasses significantly improved vision knowledge, eyeglasses usage and spectacle adherence.

Yi et al 66 in China incentivised teachers to remind children to wear their spectacles in class, significantly increasing spectacle wear by the end of the study (68.3% vs 23.9%) compared with the control group who received neither free glasses nor teacher incentives. In Vietnam, a school-based eye health promotion intervention88 included presentations, posters, brochures and training of school staff by primary eyecare personnel. This led to increased eye examination uptake (from 63.3% to 84.7%) and higher spectacle wear rates (from 36.1% to 43.4%).

In Turkey, an eight-course-hour eye health promotion programme was delivered using a booklet and compact disc for children and solely a booklet for parents.89 The intervention significantly improved spectacle-wearing, eye examination uptake and eye health-protection behaviours.

School programmes present a valuable opportunity to provide eye health services to over 700 million children worldwide. However, most programmes are narrow in scope and lack integration with the Ministries of Health and Education, which hinders their sustainability. Even in high-income countries like the USA, poor coordination leads to low uptake of school-based eyecare services.90 91 A recent study in the state of Michigan92 found significant racial and ethnic disparities in eyecare utilisation in poorer communities. Among those examined, 60.8% had worn glasses, but only 24.1% still had them, and 74% needed new glasses. Similar prescription rates (67–84%) have been reported in poorer preschools and middle schools.93–96 Furthermore, only 20–50% of poorer children referred for advanced care receive it.90 97 98

In LMICs, school-based eyecare services are often led by NGOs with limited input from the Ministries of Health and Education,99 causing inefficiency by pulling specialists away from their regular duties. Some African governments are adopting mobile health vision assessment tools, enabling teachers to conduct assessments. This task shifting, with clear referral criteria, has been proven effective.100 101 Efforts are now focused on improving referral adherence to ensure that children identified at school receive advanced care. The most effective programmes integrate eye health services with existing school health and nutrition programmes.

In Zanzibar, a 63.7% referral adherence rate was achieved when eyecare services were integrated with a school food programme compared with 46% for standalone services. Spectacle wear adherence at 6 months was 71% for the integrated model vs 13.3% for the vertical model.102

China, accounting for half of all children with refractive error globally,103 has prioritised eye health with a national myopia management plan announced in 2018.104 National policies now incorporate the effectiveness of myopia prevention among children and adolescents into governmental performance evaluations. These policies also require that primary and secondary school students receive at least one vision screening each semester, with prompt referrals as needed. The prevention and control of myopia in children and adolescents are strategic focuses of China’s ‘14th Five-Year’ National Eye Health Plan (2021–2025), which outlines a clear aim to strengthen the eyecare service system, enhance workforce quantity and quality, and expand quality eyecare services to community levels. Various public education initiatives have also been launched to raise awareness about eye disease prevention and management.105 With government leadership and cross-sector collaboration, the overall myopia prevalence among Chinese children and adolescents fell in 2022 to 51.9%; a 0.7% decrease from 52.6% in 2021 and a 1.7% decline from 53.6% in 2018.106 107

In India, school myopia is a growing concern, with refractive error prevalence at 10.8% in 2018.108 Another study indicated a fivefold prevalence increase over two decades, with an expectation of a further 10% rise by 2030.109 Although school vision screening is part of the National Program for Control of Blindness and Vision Impairment, achieving high referral uptake remains a major challenge.57 110

Substantial government investments, coordinated between the Ministries of Health and Education, can tip the global balance towards better vision and learning opportunities for children. The case for providing vision care in schools must be made clearly and forcefully to governments: strong evidence shows that vision care improves learning as effectively as any other school-based healthcare intervention5–10 and that good vision supports overall learner well-being. Recent research also highlights that good vision in children is linked with better mental health.19

Government action to treat and prevent myopia can only be effective when progress is measured with accurate, widely used tools. As a part of achieving Universal Health Coverage, the 2019 WHO Report on Vision called for the use of Effective Refractive Error Coverage (eREC) as a metric to assess progress toward delivering glasses to all children needing them. eREC assesses the proportion of children needing glasses (uncorrected vision<6/12 in the better-seeing eye) and who receive glasses improving vision to≥6/12. Governments and their partners must measure and report progress of their efforts to reduce children’s burden of uncorrected refractive error using eREC, with stratification by gender and locality.

To support the achievement of the Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly endorsed 2030 target on eREC, the WHO SPECS 2030 initiative was launched on 14 May 2024.111 The target is to achieve a 40 percentage point increase in eREC by 2030. This initiative intends to address long-standing challenges to increase both the quantity and quality of refractive services by calling for coordinated action across five pillars aligned with the letters of the SPECS acronym:

Currently, the Global SPECS Network membership consists of 31 inaugural member organisations that represent intergovernmental or NGOs, academic institutions and philanthropic foundations.

A key area requiring government action is enhanced support for refraction training, as called for in the WHO SPECS 2030 initiative.111 In many countries with substantial burdens of uncorrected children’s refractive error, such as Vietnam, optometrists have only recently been recognised as an independent discipline and specialised training institutions have been established. However, there remains a shortfall in the number of trained professionals required.112 In other countries, refractive services are delivered by ophthalmologists, nurses or other healthcare workers, without a specialised cadre of refractionists. In many settings, government regulation of refractive services is either non-existent or minimal, with practitioners regulated on the same level as beauticians or hairdressers. A sufficient cadre of well-trained and well-regulated eyecare workforce is an absolute requirement to deliver adequate refractive services in schools and beyond.

In tandem with building service capacity, enhancing demand for refractive services also requires government action.111 School-based screening and awareness programmes require coordinated support of various government bodies, as evidenced by China’s national programme,104 spearheaded by the Ministry of Education and supported by a variety of ministries, including Health and Commerce. China’s programme also features strong emphasis on myopia prevention, setting maximum allowed homework burdens and concrete local targets for reduction in prevalence.

School vision programmes must also coordinate with the healthcare community locally, so that children identified with less common problems not treatable by glasses, such as strabismus, amblyopia and paediatric cataract and glaucoma, can be referred and treated. Access to rehabilitation services will also be needed for those children whose vision impairments cannot be treated to maximise their functioning in the classroom and other environments.

The government support required to achieve these ambitious goals is substantial, and collective advocacy across the vision sector is needed to unlock these investments. This has been and will be delivered through bodies such as the WHO and IAPB, as expressed in the SDGs and the World Report on Vision, as well as regional and national Eye Health Programs. The World Bank and other multilaterals have played an important role in supporting the testing and delivery of novel models for the delivery of school vision services. Furthermore, the Research Consortium for School Health and Nutrition, which is the evidence-generating arm of the global School Meals Coalition, can assemble and distil existing evidence to guide priority setting and decision-making in this area.

The vision research community also has an important role to play in catalysing government action to support school vision programmes. Existing trial data demonstrating the educational benefits of glasses are largely limited to China and the USA. Additional trials are needed in regions and countries such as Africa and India as the potential for glasses to improve learning depends on local epidemiology and existing capacity of education systems. More data on the cost-effectiveness of school vision screening, addressing a wider variety of models, are needed.113 Furthermore, no trials to date have addressed the fundamental question of whether school vision screening interacts synergistically with interventions to improve education outcomes through teacher training. Finally, relatively little is known about the potential of combining vision screening with other programmes such as hearing assessment to increase impact and improve efficiency.85

The resources exist to eliminate uncorrected myopia as a major cause of vision impairment in children, and schools will play a crucial role in achieving this aim. Harnessing government resources will be essential for action, and the vision community can only unlock these investments by speaking with a unified voice about the need for action, the best approaches to use, and the concrete educational benefits of a world without needless child vision loss.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.