BMC Nutrition volume 11, Article number: 65 (2025) Cite this article

Pregnant women require specific dietary intake to optimize fetal development and support mother’s health. The ongoing crises in Lebanon: the economic crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Beirut port explosion, limited the population’s overall ability to consume a well-balanced diet, preventing adequate consumption of fresh, whole food and possibly disrupting people’s eating habits, notably for pregnant women. Given the vulnerability of pregnant women to malnutrition and diseases during those times, research on the nutrition status and intake of pregnant women is urgently needed to inform targeted policies and programs. This study explores nutritional status (malnutrition and anemia), food insecurity, and diet quality, and associated factors in Lebanese adult pregnant women residing in Lebanon.

A cross sectional study was conducted on a representative sample of 500 adult Lebanese pregnant women who were in different pregnancy trimesters, between March and October 2023. Collected data included sociodemographic and medical characteristics, anthropometrics, serum hemoglobin, food security status, and diet quality using validated tools.

A total of 38.6% of the participants had anemia, with more than half (53.8%) reporting not taking iron supplements. Food insecurity prevalence was 14.6% based on the “Food Insecurity Experience Scale” and 22.6% based on the “Arab Family Food Security Scale”. Although most women in the sample (79.2%) had a high minimum dietary diversity (MDD-W) score and an acceptable household dietary diversity, however; around 38% and 81.6% of them had low adherence to the Mediterranean Diet (MD) and the USDA dietary guidelines, respectively. Being in the second (aOR: 1.77) or third (aOR:1.88) pregnancy trimesters increased the likelihoods of anemia; while being employed (aOR: 0.46) and having a higher household income (aOR: 0.639) decreased the likelihood of maternal anemia. Living in a crowded household (aOR: 0.072) decreased the odds of high MDD-W, while being employed (aOR: 2.88), being food secure (aOR: 1.76) and living in the North and Akkar (aOR: 2.44) or South and Nabatieh (aOR: 2.06) increased the odds of high MDD-W. Being food secure (aOR: 1.87) increased the likelihood of fair to very good MD adherence, while having a higher household income (aOR: 0.57) decreased adherence to MD. A higher household income (aOR: 0.57) decreased the adherence to USDA dietary guidelines.

Anemia, compounded by low levels of iron supplementation and low adherence to healthy diets, warrant immediate public action given the detrimental effects they have on pregnancy outcomes. National comprehensive nutrition policies and interventions are thus needed to enhance adherence to healthy diets and the overall health of pregnant women. This also requires improving the food security situation of Lebanese pregnant women, as our findings showed that food security increases the odds of dietary diversity and adherence to the MD.

Pregnant women have increased nutritional requirement and failing to address those puts them at a heightened risk of malnutrition [1] and negative short- and long-term effects on offspring’s health [2]. As such, proper nutrition during pregnancy is vital to promote the physical health and well-being of both the mother and the growing fetus and avoid negative pregnancy outcomes [3]. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) promotes diversified diets as an approach to improve the micronutrient intake of women, especially those of childbearing age, pregnant, or lactating [4]. Among those praised diversified diets, a recent study revealed that adherence to the Lebanese Mediterranean diet (MD) is associated with improved maternal and infant outcomes in a cohort of pregnant women [5].

Despite its critical role in supporting pregnant women’s health, eating a well-balanced and diversified diet could be challenging to secure in some situations and jeopardized by many factors, such as maternal education, and psychosocial and economic conditions [6]. Specifically, the major food insecurity (FI) aspects commonly known—stress and food scarcity— are linked to detrimental dietary changes [7, 8]. Household FI is associated with an excessive gestational weight gain and other pregnancy complications such as pre-eclampsia, pre-term delivery, and gestational hypertension [9], as well as poor maternal diet quality and diversity [10]. Taken together, these factors result in poor diets lacking essential nutrients during pregnancy, particularly iron, folate, zinc, calcium, and iodine [11]. Subsequent deficiencies in these nutrients during pregnancy are suggested to be associated with anemia, hemorrhages, and death in mothers [11]. Among those complications, anemia, caused by iron deficiency, is the most prevalent micronutrient shortage during pregnancy due to increased iron needs [12]. It has detrimental effects on both mothers and offspring, such as impairing fetal growth, increasing the risk of excessive blood loss during labor, compromising maternal body’s ability to combat infections, and anemia in the offspring [13, 14]. Due to its long known aforementioned critical role during pregnancy, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends systematic iron supplementation for all pregnant women since the 1950s [15]. In addition to iron, folic acid is another critical nutrient during pregnancy, and maintaining adequate levels before and throughout pregnancy through diet and supplementation is essential to prevent birth defects [15].

Although the typical Lebanese MD has been documented for its positive association with pregnancy outcomes, the current situation in Lebanon has made it complicated to properly access fresh, diverse, and nutritious food [16]. Alongside the socio-political unrest and refugee crisis, the economic hardships and financial devaluation have inflated food security concerns in the country and severely compromised consumption of well-balanced and diverse diets. A recent nationally representative study highlights alarming levels of FI in Lebanon, affecting 47.3% of households [17]. Increased FI threats the nutritional status of Lebanese households [17, 18], especially among pregnant women being more vulnerable to malnutrition and diseases [19]. In addition, recent data reveal a maladaptive shift in the dietary habits of Lebanese adults, with diets increasingly lacking essential vitamins and minerals, putting Lebanese women of reproductive age at a heightened risk of developing anemia, osteoporosis, and other nutrition-related non-communicable diseases [17, 20].

As the risks of anemia is heightened during pregnancy [3, 4, 19], and considering the ongoing crises and increased FI levels in Lebanon and their impact on nutritional health, it is crucial to assess the prevalence of malnutrition, anemia, and FI among Lebanese pregnant women [21]. To date, most studies done in Lebanon post-COVID-19 and financial collapse were conducted among Syrian refugee pregnant women, warranting research targeting specifically Lebanese pregnant women. This is essential to develop targeted policies and interventions to promote healthy nutrition within this vulnerable population. Prioritizing maternal nutrition as a key strategy in addressing malnutrition and its harmful health effects is a vital investment in improving maternal and child health [22]. This study as such explores nutritional status (malnutrition and anemia), FI, and diet quality and associated factors in Lebanese adult pregnant women residing in Lebanon.

A cross-sectional survey that involved a representative sample of Lebanese pregnant women (N = 500) was conducted between March and October of the year 2023.

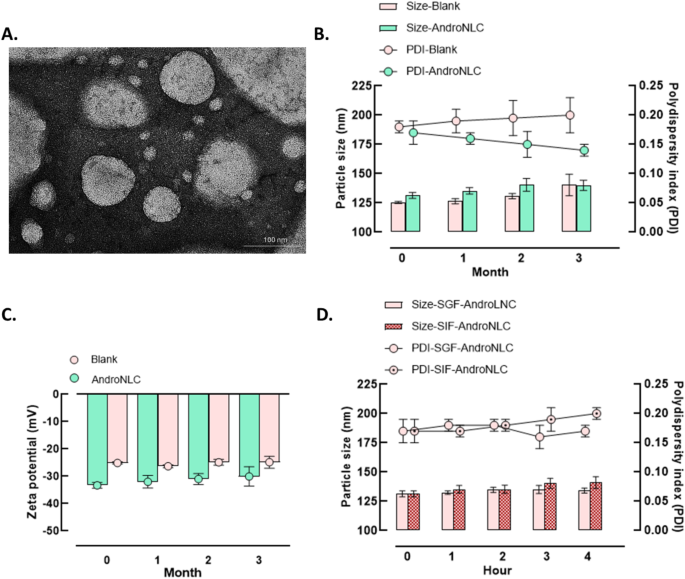

Conforming to a report by the Lebanese Republic’s Central Administration of Statistics 2018–2019 concerning the number of women in reproductive age (18–49 years), the size of the population was N = 1,244,000 [23]. The sample size was calculated using the following formula [24], with 95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error: n = (t2N)/(t2+ (2e)2(N-1)) where “n” represents the sample size, “N” represents the size of the initial population, “t” represents the margin coefficient deducted from the level of confidence (1.96), “e” represents the margin of error (5%). Overall, a total of 384 pregnant women were needed for the sample to be representative. To account for the nonresponse rate and to increase the precision of the estimates, rounding the sample to reach 500 participants was considered. Out of 600 reached pregnant women, 70 did not respond, implying an 11.7% non-response rate. Participants were recruited by using a stratified proportional sampling technique to cover all Lebanon. The recruitment process involved using multiple networks, including pregnant women identified in hospitals, private clinics, medical and primary health care centers. Gynecologists were cooperative in the early stages of the study, either by facilitating the process of reaching pregnant women and occasionally informing pregnant women about the study and explaining the study objectives, or by welcoming the dietitians and agreeing to meet with their patients. A representative sample was taken from each governorate using the formula descried previously. The distribution of the study participants across the governorates is shown in Fig. 1.

Distribution of study participants based on governorates [25]

Data were collected by trained dietitians who approached potential participants from multiple networks, including private clinics, hospitals, medical centers, and charitable organizations. The trained dietitians assessed eligibility, recruited participants and assisted them in filling the questionnaire. Eligibility criteria included: Lebanese, currently pregnant woman at different gestational stages, aged between 18 and 49 years, living in Lebanon, not having chronic diseases, not having developed pre-eclampsia or gestational diabetes during pregnancy, and not lactating—unless the woman was pregnant and still lactating a child at the same time.

The survey, including all the study tools, was conducted face-to-face by trained dietitians, in addition to collecting the participants’ anthropometric measures. The survey required forty-five minutes to be filled. It was translated from English and administered to participants in Arabic, which is the native language of participants. Before administering the survey, the Arabic version was pilot tested for validity, context specificity, and clarity. The pilot testing helped evaluate the time required to fill the survey and to detect and rule-out issues with data gathering and the data entry. The pilot testing targeted 30 pregnant women not involved in the current study. Following the pilot testing, the tool was deemed applicable and clear, with minor adjustments made to the wording.

Demographic, personal, and health-related information

Information collected included age, current place of residence, marital status, household size, numbers of rooms in the house, women educational level, partner educational level, current occupation, monthly household income, the salary earning after the economic crisis’s, number of children, pregnancy status, dietary supplements intake during pregnancy. Household size and numbers of rooms were recorded to compute the crowding index, which is a reflection of the household’s socioeconomic status [26].

Participants’ anthropometric measurements and hemoglobin test measurement

Collected data included mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) and serum hemoglobin of participants. MUAC, which is an indicator of a pregnant woman’s nutritional status, was measured by using a measuring tape around the arm circumference and a value between 22 and 27.6 cm was considered as normal [27, 28]. Based on literature review [28], values below 22–23 cm are strongly indicative of a pregnant woman being risk of having a low-birth weight child.

Hemoglobin level was marked on the spot through “DiaSpect Tm Hemoglobin Analyzer”. This is an accurate and reliable test that has higher sensitivity compared with other techniques [29, 30]. Hemoglobin levels less than 11 g/dl indicated the presence of anemia [31].

Household food security

Food security status was assessed using the “Arab Family Food Security Scale” (AFFSS) and the “Food Insecurity Experience Scale” (FIES), which are validated to be used in League of Arab States countries, including Lebanon [32, 33]. The AFFSS included questions indicating households’ food security status during the last six months. Participants’ responses were marked by ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Do not Know’. Individual scores were added and those with a score ranging from 0 to 2 were considered to have high food security, those with scores from 3 to 5 were considered as moderately food insecure, and those with scores from 6 to 7 were considered as severely food insecure [33]. As for FIES, eight questions concerning participants’ access to adequate food during the past twelve months were asked, and participants were classified as either “food secure” if the score is less than or equal to three, “moderately food insecure” if the score was between 4 and 6 and “severely food insecure” if the score was 7 or 8 [34].

Food consumption questionnaire

The food consumption score (FCS) is the most widely used food security and dietary diversity indicator globally [35]. This part collected participants’ dietary habits by asking about the numbers of meals consumed during a 7-day reference period, and asking if it is less, same, or more than usual by using the FCS questionnaire. Profile of the household FCS was classified into three categories: a score between 0 and 21 was considered ‘poor’; 21 to 35 as ‘borderline’; and a score greater than 35 was considered as ‘acceptable’ [35].

Food frequency questionnaire (FFQ)

This section included a validated FFQ [36] divided into twelve food groups (see Supplementary File). To facilitate the estimation of frequency of food consumption to participants, the number of portions was estimated through food models and food photos showed to them. The frequency of food consumption was divided into four categories: daily, weekly, monthly and never, and were transformed into daily intake in grams for each participant.

24-hour recalls

24-hour recalls were collected on three non-consecutive days (Monday, Thursday, and Sunday). Participants were asked to recall all the foods and beverages they consumed during the previous day with visual aids being provided to help them remember and better estimate the portion sizes.

After collecting the data, items were classified in groups similarly to the FFQ food groups, and the average of the 3 days for each group was computed by dividing the amount consumed in grams (g) by three. After this, the average consumption was obtained by computing the average of each item from the FFQ and 24-hr recall by adding both values and dividing the result by two ((g FFQ + g 24-hr recall)/2). Items not present in the FFQ but were reported in the 24-hr recalls were added separately by averaging the three 24-hr recall values only.

Minimum dietary diversity (MDD-W)

The participants’ dietary diversity was computed based on the collected 24 h dietary recall mentioned in the previous section by assessing the consumption of 10 food groups (grains/white roots/tubers, pulses, nuts or seeds, dairy, meat/poultry/fish, eggs, dark green leafy vegetables, other vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables, other vegetables, other fruits) [4]. Based on this indicator, participants who consumed at least five out of the ten food groups of concern were said to have consumed their minimum dietary diversity and eventually have higher micronutrient adequacy compared to participants who consumed less than five groups [4].

Adherence to the mediterranean and USDA dietary guidelines

The 14-item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (14-MEDAS) was used to assess adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MD) [37]. This tool is widely used in literature and was validated in several studies [38,39,40,41,42,43]. The final 14-MEDAS score ranges from 0 to 14; whereby a score of ≤ 5 denoted weak adherence, 6–9 moderate to fair adherence, and ≥ 10 good or very good adherence. For the adherence to USDA dietary guidelines, food groups were categorized according to the USDA’s pregnancy guidelines [44] using data collected from the FFQ [36]. The consumption of each food group was divided into two categories according to the USDA’s cutoff points and every food group received a score of either 0 or 1, where 0 denoted consumption below the USDA’s daily recommendations and 1 denoted consumption above them [44].

The “Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, the IBM SPSS Statistics 21” was used for data analysis at a 95% confidence interval. Descriptive statistics summarized quantitative variables using frequencies, percentage, means and standard deviations. Comparative statistical tests such t-tests, ANOVA were performed to compare means across groups. Chi-square test was used to check association between variables. Backward logistic regression models were performed to assess the determinants of the dependent variables (anemia, MDD-W, adherence to MEDAS and adherence to USDA dietary guidelines) at a 95% confidence level. The choice of variables was based on literature review and bivariate analysis whose results are shown in Additional File 1.

The study was approved by The Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the Higher Center for Research (HCR) at the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (USEK) on 13/01/2023. Questionnaires were anonymous, and developed based on the no-harm principle, and all data collected was kept confidential and was used for academic purposes only. Conforming to the declaration of Helsinki fixed in 1964, data gathered from the study respondents was treated as confidential and only used for study purposes. All gathered data stayed anonymous. Before the start of data collection, a written informed consent was sought from each participant prior to data collection, whereby participants were informed about the purpose of the survey, the type of questions included within the questionnaire, and re-assured that all data collected will be solely used for the purpose of the study with full respect to safeguarding data anonymity and confidentiality. In addition, data collection took place in closed areas ensuring the participants’ privacy and all gathered questionnaires were kept in a locked place and all computerized data was safeguarded on the researcher’s password protected computer.

The sociodemographic and medical characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants (65.8%) were aged 30 years or below. Almost half of the participants resided in Beirut and Mount Lebanon (49.2%) and were in the second trimester of pregnancy (51.8%). Less than 1% of participants had malnutrition based on MUAC measurements. More than half of the participants had normal hemoglobin levels, while 38.6% were found to have low hemoglobin levels, i.e., anemia. Less than 40% of the participants reported taking multivitamin supplements, more than half (53.8%) of them reported not taking iron supplements and 41.4% reported not taking folic acid supplements. Supplementation per pregnancy trimester is available in the Additional File 1, Table S1.

Food security status of the households is presented in Table 2, in the total sample and based on sociodemographic characteristics. Based on the AFFSS, 77.4% of participants were food secure; the highest FI prevalence was found in North Lebanon and Akkar (38%) and the lowest in Beqaa and Baalbeck-Hermel (16.1%). Based on the FIES, 85.5% of participants were food secure; the highest FI prevalence was in North Lebanon and Akkar (28%) and the lowest prevalence in Beqaa and Baalbeck-Hermel (8.9%). More than 85% of participants in all governorates were food secure except for North/Akkar, where 72% were food secure. 86.5% of the non-crowded households were food secure compared to 30% for the crowded households being food secure.

Based on the AFFSS, among food secure women, 86.3% had an acceptable FCS while 75.2% of women with FI had an acceptable FCS (p-value = 0.005). The prevalence of high DDS was 82.7% among food secure women while it was significantly lower (67.3%) among women with FI (p-value < 0.001). Additionally, fair to moderate adherence to the MD was 64.9% among food secure women while it was significantly lower (54%) among women with FI (p-value = 0.036). Similar results were obtained based on the FIES. For instance, among food secure women, the prevalence of acceptable FCS was 85.9% while it was significantly lower (71.2%) among women with FI (p-value = 0.002). Similarly, the prevalence of high DDS was 81.5% among food secure women while it was significantly lower (65.8%) among women with FI (p-value = 0.002). In addition, the prevalence of fair to moderate adherence to the MD was 64.2% among food secure women while it was significantly lower (52.1%) among women with FI (p-value = 0.048).

Concerning anemia status, based on the two food security scales, anemia was less prevalent in food secure participants. For instance, based on the AFFSS, the prevalence of anemia was 35.1% among food secure women while it was significantly higher (50.4%) among women with FI (p-value = 0.003). Similarly, based on the FIES, the prevalence of anemia was 35.8% among food secure women and was significantly higher (54.8%) among women with FI (p-value = 0.002).

A summary of these results is shown in Table 3. Overall, the findings reveal that food secure pregnant women are less likely to have anemia and more likely to have an acceptable FCS, a higher dietary diversity, and a better adherence to the MD. Overall, 79.2% of participants had a high MDD-W score and 83.8% had an acceptable household FCS. However; 37.6% of women had low adherence to the MD and the majority (81.6%) had low adherence to the USDA dietary guidelines.

Table S2 shows the variables significantly associated with anemia in our study sample. These variables were entered in the model. The determinants resulting from the regression are shown in Table 4. Being in the second trimester of pregnancy was associated with an increased likelihood of having anemia by 1.77 times compared with the first trimester (aOR = 1.77, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.05–2.97), and being in the third trimester was associated with almost twice the likelihood of anemia (aOR = 1.88, 95% CI = 1.07–3.29). Being employed was associated with lower likelihood of having anemia (aOR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.313–0.675) and having a higher household monthly income was negatively associated with having anemia (aOR = 0.639, 95% CI = 0.43–0.95).

Table S3 shows the variables significantly associated with high MDD-W score among pregnant women in our study sample. These variables were entered in the model. The determinants resulting from the regression are shown in Table 5. Living in a crowded household was associated with a lower likelihood of having a high MDD-W score compared with living in a non-crowded household (aOR = 0.072, 95% CI = 0.013–0.387). In addition, being employed was associated with a higher likelihood of having a high MDD-W score by about threefold (aOR = 2.88, 95% CI = 1.77–4.67). Moreover, food secure participants were 1.76 times more likely to have a high MDD-W score compared with participants having FI (aOR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.048–2.97). Based on governorates, participants residing in North Lebanon and Akkar were 2.44 times more likely to have a high MDD-W score compared with participants residing in Beirut and Mount Lebanon (aOR = 2.44, 95% CI = 1.27–4.67). Furthermore, participants residing in South Lebanon and Nabatieh were twice more likely to have a high MDD-W score compared with participants residing in Beirut and Mount Lebanon (aOR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.07–3.98).

Table S4 shows the variables significantly associated with the 14-MEDAS among pregnant women in our study sample. These variables were entered in the model. The determinants resulting from the regression are shown in Table 6. Being food secure was associated with an increased likelihood of adherence to MD by almost twofold (aOR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.2–2.92). In addition, having a higher household monthly income was associated with a decreased likelihood of adherence to MD (aOR = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.39–0.84).

Table S5 shows the variables significantly associated with adherence to USDA dietary guidelines among pregnant women in our study sample. These variables were entered in the model. Household monthly income was the only variable associated with a higher adherence in our study sample, whereby having a higher income was associated with a lower likelihood of adherence (aOR = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.35–0.93, and p = 0.024) (Table 7).

This study pioneers in assessing the prevalence and predictors of malnutrition, anemia, and diet quality in a nationally representative sample of Lebanese pregnant women amid a multifaceted crisis. Even though prevalence of malnutrition was less than 1%, a total of 38.6% of pregnant women had anemia, with more than half (53.8%) reportedly not taking iron supplements, and almost 40% not taking folic acid supplements, both of which are essential micronutrients during pregnancy [21]. These findings are particularly alarming since the lack of supplementation dramatically increases preventable risks of maternal anemia, pre-term birth, low birth weight, and neural tube defects [45].

First and foremost, the prevalence of anemia in our study population is significantly higher than global averages for anemia among pregnant women (31.15%). It also seems to follow a worrisome trend with a 10% increase compared with pre-crises prevalence (27.7% in 2019) [46], reflecting an unfortunate deterioration in the health of Lebanese pregnant women. Sociodemographic determinants of health like unemployment and lower income were documented to increase the likelihood of anemia in our study population. Employed pregnant women might have better knowledge and better financial means to adopt a healthier and diversified dietary behavior characterized by better health decision-making and consuming nutritious food, associated with decreased odds of anemia [47]. This in in line with similar findings whereby pregnant women with lower income have higher odds of having anemia like in China for instance [48]. Yet concerning unemployment, some contradictory results were found in India, where employed pregnant women had a higher likelihood of having anemia compared with unemployed pregnant women [49]. In our study population, being in the second or third pregnancy trimester compared with the first, increased the odds of having anemia, like in Belgium [50], and in the United States [51], where the prevalence of iron deficiency increased significantly with each pregnancy trimester. In our sample, FI was not associated with anemia; whereas other studies reported different results. For instance, FI was associated with a higher risk of anemia among pregnant women in Brazil [52] and Indonesia [53].

Based on our findings, most participants (79.2%) achieved the MDD-W, which is a higher prevalence than the global reported average for females (65%) [54]. For example, lower estimates were found in Ethiopia (44%) [55] and Somalia (51.8%) [56], and similar estimates were obtained in Northern Ghana (79.9%) [57]. Concerning the determinants of a high MDD-W, our study showed that being employed, food secure, and living in a non-crowded household increased the likelihood of having high MDD-W. Similarly to our findings, being food secure increased the likelihood of having a high MDD-W in Somalia [56], and being employed increased the likelihood of high dietary diversity in Western Nepal and Kenya [58, 59]. Potentially, food secure and employed pregnant women are able to afford food items with higher prices and eventually have more choices, allowing them to adopt a more diversified dietary behavior. As for impact of crowding index on diversity, it could be that crowded households rely on coping strategies such as decreasing the portion size or cutting off on specific groups which would decrease the odds of dietary diversity. Interestingly, based on our findings, participants residing in North Lebanon and Akkar or South Lebanon and Nabatieh were more likely to have a high MDD-W score compared with participants residing in Beirut and Mount Lebanon. This could be the advantage of rural versus urban lifestyles since Beirut and Mount Lebanon have more densely populated urban areas and more established nutrition transition, characterized by shifting from traditional dietary habits towards westernized diets high in animal-based products, ultra-processed foods, fast foods, and added sugars… [60,61,62,63].

Our findings also revealed that the diet quality in relevance to USDA dietary guidelines was poor, especially when it comes to breads and cereals, dairy products, and protein foods consumption, with more than one-third of the participants having a low adherence to the MD. Our results align with those of a study in Arab pregnant women [44], with higher estimates in Central South Africa, where 99.6% of pregnant women had low adherence to the MD [64]. Being food secure was associated with increased likelihood of MD adherence and eventually diet quality in our sample, in line with common reports in the United States [65,66,67], where food secure pregnant women have higher diet quality. However, a study that assessed diet quality in pregnant women from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999–2008) challenged this significant association between food security and diet quality [68]. Individuals with FI tend to have lower intake of dark green leafy vegetables, whole grains, and higher consumption of refined grains, added sugars and sugar-sweetened beverages, which reflects lower adherence to the MD and USDA dietary guidelines, hence poorer diet quality [69]. In addition to food security, having a higher income counterintuitively decreased the likelihood of adherence to MD and USDA dietary guidelines. Different results were obtained in the US, where higher household income was associated with higher likelihood of meeting dietary guidelines [66]. In our study sample, this might be explained by the nutrition transition that is occurring in the Lebanese population and neighboring countries; recent findings show that the Lebanese population had a low adherence to the MD [20, 70, 71] and USDA dietary guidelines [20], with the Westernized diet (characterized by increased consumption of sweets, added sugars and saturated fats) dominating the dietary patterns of the population [20, 70, 71]. Having a higher income allows individuals to afford items belonging to the highly marketed Westernized diet (fast food, sweets…) therefore leading to lower adherence to the MD and USDA dietary guidelines.

FI, often resulting from consecutive crises, negatively affects the health of pregnant women. For instance, economic hardships, electricity and power cuts alongside disrupted supply chains can limit the availability and affordability of nutritious foods, prompting families to choose cheaper, calorie-dense, nutrient-poor alternatives. This dietary shift also leads to a decreased adherence to MD and USDA dietary guidelines, known for their numerous health benefits, including reducing the risk of chronic diseases and supporting maternal health. In spite of FI not being associated with anemia in our sample, participants had a high MDD-W score: potentially even if pregnant women had insufficient intake, they may have still consumed foods that are high in iron, such as legumes, lentils, pulses, and leafy greens, preventing anemia despite being FI.

The difference of our results compared with other studies might be due to many factors including methodological approaches and cultural differences in food intakes. There are several tools that can be used to assess FI different than the ones we used such as the North American Food Security Assessment Scale [53] and the United States Household Food Security Survey Module [53]. Similarly, many different scales are used when assessing diet quality such as the Healthy Eating Index-2005 and the Alternate Healthy Eating Index-2010 [65, 66], 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans [66], the Dietary Guidelines Adherence Index 2015 [67], and the Alternate Healthy Eating Index modified for Pregnancy [68]. Also, different sampling techniques and different data collection tools used among studies can lead to different results.

Lastly, as these nutrition challenges persist and worsen in pregnant women, dealing with them calls for a comprehensive approach involving immediate and long-term strategies. Sustainable solutions must be implemented to address the current preventable escalation of health issues and additionally enhance resilience against future crises, including investing in local agriculture to ensure food sovereignty, strengthening social safety nets to support vulnerable populations, and promoting public health interventions that encourage adherence to healthy dietary patterns. International and local non-governmental organizations, nutrition, and medical associations play an important role when it comes to maternal health, especially during crises. Integrating nutrition into primary healthcare, raising awareness about the importance of nutrition especially during pregnancy, screening for reproductive system diseases, family planning, as well as antenatal and postnatal care services are among the different approaches that can be used to support pregnant women in pre-, amid, and post-pregnancy.

The main strength of this study is being the most recent analysis of the dietary patterns and nutritional status (anemia, malnutrition) of Lebanese pregnant women amidst the protracted socio-economic and health crises, providing essential perspectives into this important issue. Moreover, the study utilized an in-person assessment of a nationally representative sample from all Lebanese governorates, allowing the results to be generalized to the Lebanese pregnant women population. Additionally, this is the first study to assess the determinants of anemia, dietary diversity and adherence to two healthy diets (MD and USDA) on a nationally representative sample in this vulnerable population, adding an aspect to the literature that has not been assessed at a national level. However, this study has some limitations. The data collected were self-reported, which can lead to inaccuracies due to recall bias, potentially causing errors in estimating portion sizes and the under- or over-reporting of food consumption. In addition, there is a potential for bias in data reported due to social desirability. Moreover, there is no established cutoff value for MUAC to be used in the Lebanese population; the cutoff that we adopted might affect the accuracy of the results related to MUAC. In addition, pre-pregnancy BMI was not calculated, being based on self-reported data that could be subject to inaccuracies. Additionally, factors such as food accessibility, seasonality, personal preferences, traditions, religions and beliefs can affect the adherence to dietary guidelines. Finally, the scarcity of nationally representative studies that assessed food security, anemia, and diet quality in this population limits the comparison with exclusively nationally representative studies.

In conclusion, the prolonged consecutive crises intricately impacting malnutrition, anemia, FI, and poor dietary habits in pregnant women emphasize the critical need for comprehensive public health strategies. These should aim not only to alleviate immediate nutritional deficiencies but also to foster long-term resilience through education, support for local food systems, and improvements in healthcare. Additionally, short-term immediate actions must be implemented based on the results of this study, such as nutrition supplementation and fortified food aid which are paramount to safeguarding the overall health and well-being of pregnant women in times of crises, and this requires the collaboration of international and local non-governmental organizations, as well as nutrition and medical associations.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- AFFSS:

-

Arab Family Food Security Scale

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DDS:

-

Dietary Diversity Score

- FCS:

-

Food Consumption Score

- FFQ:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- FI:

-

Food Insecurity

- FIES:

-

Food Insecurity Experience Scale

- HCP:

-

Healthcare Providers

- MD:

-

Mediterranean Diet

- MDD-W:

-

Minimum Dietary Diversity

- MEDAS:

-

Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener

- MUAC:

-

Mid-upper Arm Circumference

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- USDA:

-

United States Department of Agriculture

We would like to thank Maroun Khattar for helping in drafting the manuscript.

This project received no external funding.

The study was approved by The Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the Higher Center for Research (HCR) at the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (USEK) on 13/01/2023. An oral consent was obtained from subjects prior to participation. Questionnaires were anonymous, and developed based on the no-harm principle, and all data collected was kept confidential and was used for academic purposes only. Conforming to the declaration of Helsinki fixed in 1964, data gathered from the study respondents was treated as confidential and only used for study purposes. All gathered data stayed anonymous. Before the start of data collection, a written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. Participants were well-informed about the study purposes, the sections of the questionnaire, and the estimated duration of data collection. In addition, data collection took place in closed areas ensuring the participants’ privacy and all gathered questionnaires were kept in a locked place and all computerized data was safeguarded on the researcher’s password protected computer.

Not Applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Mahfouz, R., Sacre, Y., Rizk, R. et al. Anemia and food insecurity: the nutritional struggles of pregnant women in Lebanon amid unprecedented crises. BMC Nutr 11, 65 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-025-01042-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-025-01042-0