BMC Psychology volume 13, Article number: 550 (2025) Cite this article

Dental education is considered a highly stressful training process that can lead to high levels of stress, anxiety and depression, which can affect wellbeing and performance. Moreover, after the completion of training, working as a dentist is a stressful occupation due to direct interactions with patients and the necessity of carrying out complicated dental procedures in the vulnerable area of the patient’s mouth. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate stress, anxiety, and depression levels experienced by dental students compared to those among dentists.

A cross-sectional survey was carried out involving 42 general dentists (graduates of Tel-Aviv University) and 73 dental students in their clinical years (fifth and sixth years at Tel-Aviv University). Psychological wellbeing was assessed using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), which measures the severity of psychological distress via a reliable self-rating questionnaire.

The overall prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among dental students was 54.79%, 58.9%, and 57.53%, respectively, and the overall prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among dentists was 23.8%, 21.5%, and 21.4%, respectively. Significant differences were found in relation to DASS categories (normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe) for depression (p = 0.005), anxiety (p = 0.003), and stress (p = 0.002), with higher levels of psychological symptoms of anxiety, stress, and depression observed in clinical dental students and lower levels observed in dentists. No significant differences were found between male and female participants regarding mean DASS scores for depression, anxiety, and stress across all study groups (p > 0.208).

High levels of depression, anxiety, and stress were observed in clinical dental students. However, these levels significantly decreased upon becoming a dentist. No differences were found regarding gender among the two groups. However, a longitudinal study following dental students during the process of dental education and into their work life is required.

Stress is the behavioral response of an individual to threatening or challenging situations. It can lead to anxiety, which is often accompanied by a hyperactive autonomic nervous system. Symptoms may include sweating, sleep disturbance, fatigue, abdominal disturbance, and depression with intense mood swings. These mental disturbances can subsequently impair cognition, learning ability, and academic or clinical performance [1,2,3,4,5].

Dental education is considered a highly stressful training process [1] that can lead to high levels of perceived stress, anxiety, and depression, which may affect the wellbeing and performance of dental students [5]. Dentistry is a stressful occupation due to several factors, including direct interaction with patients and engagement with complicated dental procedures in the patient’s mouth. This may result in reduced performance, lower productivity, and professional burnout [6], in addition to threatening the physical health of patients [7]. According to the current literature, persistent stress can eventually lead to psychological morbidity and increase the risk of suicidal intent [3].

Studies have shown that gender is a risk factor, with women experiencing greater psychological distress than men [8, 9]. Radeef A.S et al. [8] concluded that dental students were exposed to high levels of psychological distress and that this was significantly more the case in women than in men. Bayram N et al. [9] reported a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among university students, with higher stress scores being reported by women.

Farokh-Gisour E et al. [10] investigated stress levels among dental students, dentists, and pediatric dental specialists, finding that specialists had significantly lower stress than dentists and dental students. Siddiqui M.K et al. [11] discovered high stress levels among young and junior dentists, and Barberia E et al. [2] explored stress levels among pre-clinical and clinical dental students, concluding that there was an increase in psychological distress levels during the transition from the pre-clinical to clinical years.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has investigated patterns of stress in the dentistry field through the process of dental education into clinical work as a dentist and which stage in this process is the most stressful. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the level of stress, anxiety, and depression experienced by dental students during their clinical year and as a dentist, with a gender comparison. Recognizing the peak of stress can help control stress in the field of dentistry, leading to better performance and more success in their career development. The hypothesis of this study was that the prevalence and severity of stress, anxiety, and depression would be higher among dental students than among dentists.

The participants of this cross-sectional survey included 42 general dentists who had graduated from Tel Aviv University (male = 22, female = 20, mean age = 37.14, range = 35) and 73 dental students in their clinical years at Tel Aviv University (male = 36 female = 37, mean age = 26.91, range = 23–33).

Students’ and dentists’ participation was completely voluntary. The principal investigator explained the research goals and their importance, and then participants had the opportunity to opt out. This study was conducted according to the guidelines of, and was approved by, the Institutional Ethics Committee (Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Tel Aviv University (protocol code 0005714-1, 5 December 2022), and all participants signed an informed consent document before participating. For anonymity, each participant was randomly assigned an identifying number known only to the principal investigator, to reduce response and desirability bias. Dentists and students who agreed to participate in the study and were undergraduates or graduates of Tel Aviv University were eligible. The research exclusion criteria applied to participants who did not give consent, had a health problem, or were receiving any psychological management (cognitive or medicated) that could be affecting their psychological status.

Psychological wellbeing was assessed using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), which measures the severity of psychological distress via a reliable self-rating questionnaire that assesses the severity of DAS symptoms experienced over the previous week [12]. Items are scored on a 4-point scale: “did not apply to me at all” (0), “applied to me to some degree or some of the time” (1), “applied to me to a considerable degree or a good part of the time” (2), and “applied to me very much or most of the time” (3) [10]. Dental students and dentists used the 4-point scale to rate their symptoms during the previous week. For continuous scores (mean and ± SD), DAS scores were calculated by summing the score of 7 statements relevant to each subscale: Stress, Anxiety, and Depression. Higher scores indicated a higher level of psychological distress. The scores for each subscale were then categorized to evaluate the symptom severity (frequency and percentage) of each condition as normal, mild, moderate, severe, or extremely severe according to the cut-off points suggested by Lovibond S.H [12].

All analyses were performed using SPSS, version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Significant statistical differences were defined as p < 0.05. Mann–Whitney tests were performed to evaluate the effects of gender on DASS scores.

Mann–Whitney tests were used for the comparison of DASS scores between dental students in their clinical year of study and dentists, while chi-squared tests were used for DASS category comparison. Three linear regression models were conducted to evaluate the influence and explanatory power of age, gender, and group (student or dentist) on anxiety, stress, and depression. A sensitivity power analysis using G*Power was used to calculate which effect size our study was sensitive enough to detect.

For comparison between dental students and dentists, Mann–Whitney tests with 73 and 42 participants, respectively, would be sufficiently sensitive to detect effect sizes of Cohen’s f = 0.56 with 80% power (α = 0.05, two-tailed). This corresponds to a medium effect size.

Cronbach’s Alpha value for the DASS questionnaire consisting of 21 items was 0.947, which indicated a high level of internal consistency. The depression subscale consisted of seven items (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.894), the anxiety subscale consisted of seven items (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.819), and the stress subscale consisted of seven items (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.891).

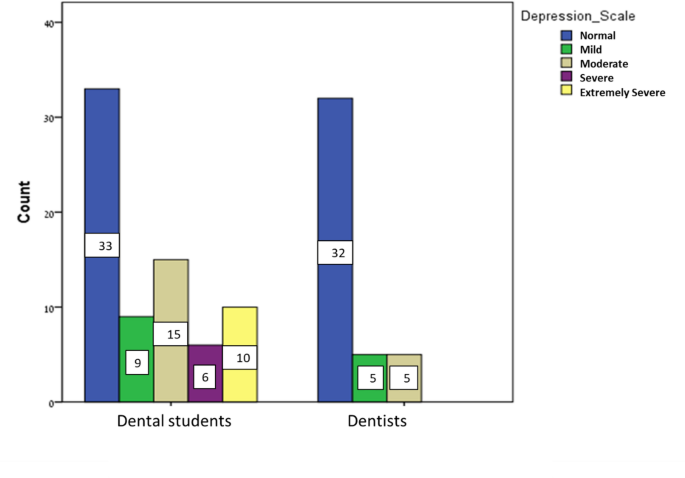

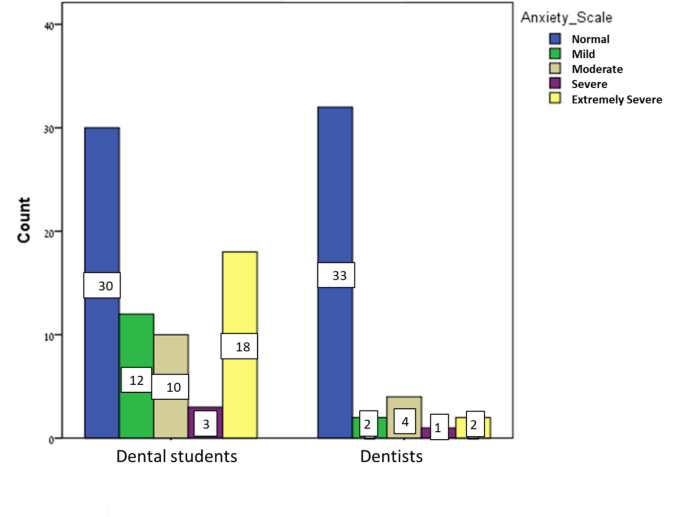

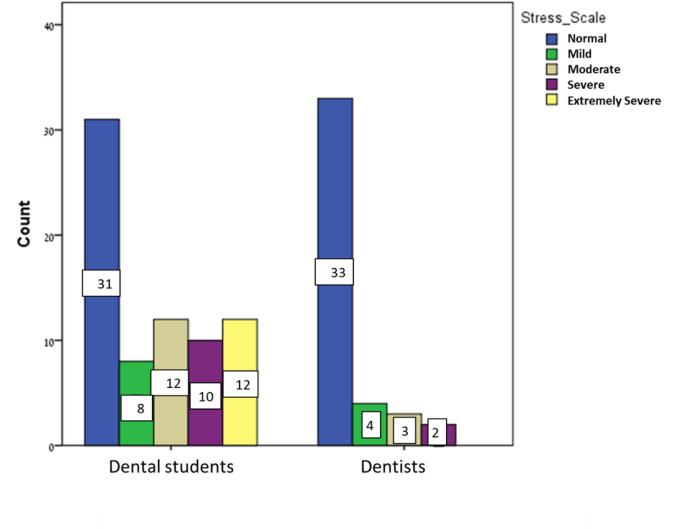

In the present study, the overall prevalence of depression among dental students (n = 73) and dentists (n = 42) was 54.79% and 23.8%, respectively. The overall prevalence of anxiety among dental students and dentists was 58.9% and 21.5%, respectively. The overall prevalence of stress among dental students and dentists was 57.53% and 21.4%, respectively (Table 1).

Severe and extremely severe depression, anxiety, and stress were experienced by 21.8% (n = 16), 28.75% (n = 21), and 30% (n = 22) of dental students, respectively. In contrast, severe and extremely severe depression, anxiety, and stress were experienced by 0%, 7.2% (n = 3), and 4.8% (n = 2) of dentists, respectively (Table 1).

Significant differences were found between dentists and students in relation to DASS categories (normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe) for depression (p = 0.005), anxiety (p = 0.003), and stress (p = 0.002), with a higher level of psychological symptoms of anxiety depression, and stress observed in dental students compared to dentists (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

The mean DASS scores of depressions (p < 0.005), anxiety (p < 0.005), and stress (p < 0.005) were significantly lower in dentists compared to dental students, Table 2.

No significant differences were found between male and female participants (dental students and dentists) in mean DASS score levels for depression, anxiety, and stress (p > 0.05), Table 2.

A linear regression analysis using the enter method was conducted with independent variables, including age, gender, and group, on anxiety, stress, and depression levels. For anxiety, the model explained 17% of the level variance (R² = 0.177, adjusted R² = 0.153) and was statistically significant (p < 0.0005). Among the predictors, only group (β = -1.56, p = 0.003) had a significant influence, with no significant effect observed for age (β=-0.053, p = 0.359) or gender (β = 0.622, p = 0.405). For stress, the model explained 17% of level variance (R² = 0.172, adjusted R² = 0.148) and was statistically significant (p < 0.0005). Among the predictors, again, only group (β = -2.016, p = 0.002) had a significant influence, with no significant effect observed for age (β=-0.057, p = 0.425) or gender (β = 0.534, p = 0.566). For depression, the model explained 14% of level variance (R² = 0.145, adjusted R² = 0.120) and was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Among the predictors, again, only group (β = -1.764, p = 0.004) had a significant influence, with no significant effect observed for age (β=-0.039, p = 0.566) or gender (β = 0.462, p = 0.595).

Total number of dental students (n = 73) and dentists (n = 42) as a function of the category reflecting their depression scale (normal, mild, moderate, severe, or extremely severe)

Total number of dental students (n = 73) and dentists (n = 42) as a function of the category reflecting their anxiety scale (normal, mild, moderate, severe, or extremely severe)

Total number of dental students (n = 73) and dentists (n = 42) as a function of the category reflecting their stress scale (normal, mild, moderate, severe, or extremely severe)

This study was designed to explore patterns of psychological distress among individuals in the field of dentistry, from the clinical years of study into professional practice as dentists. Interestingly, contrary to the notion that direct patient interaction in clinical work increases psychological symptoms, our study found that the group of practicing dentists exhibited the lowest levels of depression, stress, and anxiety. According to this study, dentists demonstrated low levels of depression (23.8%), anxiety (21.5%), and stress (21.4%). This is in contrast with other studies that have concluded that high stress is common among dentists [13, 14].

In consensus with other studies [8, 15], our study found high DASS symptoms among dental students, as the overall prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among dental students was 54.7%, 58.9%, and 57.53%, respectively. In a study by Radeef A.S et al. [8], the overall prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress was 47.5%, 67.3%, and 42%, respectively. In previous studies, we found high levels of stress among dental students in their preclinical [16] and clinical [17] years. In a study by Zulfiqarova U et al. [18], 36% of medical students displayed severe-to-very-severe generalized anxiety disorder.

According to the patterns of stress observed, psychological symptoms increase during the clinical years (fifth and sixth year at Tel Aviv University) of dentistry education. We postulate that the high levels of stress during the clinical years of dentistry studies are due to clinical requirements that necessitate the integration of theoretical knowledge, patient interaction, and care and the performance of dental procedures with a high level of manual skill. These findings are similar to those of Al-Sowygh Z.H et al. [19], who concluded that the workload and clinical requirements were the greatest stressors, with the highest levels observed during the clinical years of dentistry study. This finding is consistent with other studies that found that the main sources of stressors among dental students were academic factors [20]. Therefore, modifications must be made to the dental curriculum to enhance students’ performance, improve their emotional status, and prevent negative effects on their health.

Although female gender has been shown to be a risk factor for stress in previous studies [2, 21, 22] due to different stress coping mechanisms, in our study, women showed insignificant differences regarding stress, anxiety, and depression levels in comparison to men across all study groups.

It is important to mention that all data were collected before October 7th, and it would be very interesting to compare the results of this study with results after October 7th with the same two groups, i.e., a group of clinical students and a group of dentists. Another aspect that should be mentioned is that data were collected just after the COVID-19 pandemic and so the results may have been affected by it [23].

More than half of the students experienced some level of depression, anxiety, and stress; therefore, we recommend providing support to students during their clinical years and suggest developing different methods (courses, workshops, psychological aid, etc.) of dealing with these feelings to reduce levels of stress, depression, and anxiety.

A limitation of this research is that only the questionnaire method was used, and levels of cortisol [22] (the main stress hormone) in the blood were not assessed, preventing the direct measurement of stress levels among dental students and dentists. This study was a cross-sectional study, which did not allow for the assessment of changes in psychological status over time. Additionally, due to the self-reported nature of the questionnaire responses, we cannot rule out response bias. Another prospective longitudinal study exploring the same population, i.e., dental students and dentists, is required to confirm our results.

High levels of depression, anxiety, and stress were observed among dental students during their clinical years of study. However, these levels significantly decreased when students became dentists. No differences were found between male and female participants (dental students and dentists) in terms of depression, anxiety, and stress levels.

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Dr Gil Ben-Izhack, mail [email protected].

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Tel Aviv University (protocol code 0005714-1, 5 December 2022).

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Lugassy, D., Naishlos, S., Shapinko, Y. et al. Analysis of stress, anxiety, and depression among dental students and dentists: a cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey. BMC Psychol 13, 550 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02884-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02884-w