A Critique Of "Mental and Emotional Health of Youth after 24 months of Gender-Affirming Medical Care Initiated with Pubertal Suppression"

This is extremely time-consuming work, and I can do it only because of my paying subscribers. If you find this useful, please consider joining the thousands of people who have already purchased a premium subscription, or gifting one to a friend.

Get 20% off a group subscription

While I wanted to make this a public post, most of this newsletter’s content is paywalled, so if you join you’ll get access to a lot of other content as well as the ability to comment on articles and to participate in a Singal-Minded exclusive chat room on Substack.

For those who are already paying subscribers — thank you! You’re the reason I was able to publish this without a paywall.

Last month, a preprint of a highly anticipated study appeared online. “Mental and Emotional Health of Youth after 24 months of Gender-Affirming Medical Care Initiated with Pubertal Suppression” arrives at a time of maximal controversy on this subject in the U.S., with a major Supreme Court decision expected this month that could permanently solidify U.S. states’ ability to ban or severely restrict youth gender medicine. The authors of this preprint are Johanna Olson-Kennedy, Ramon Durazo-Arvizu, Liyuan Wang, Carolyn F. Wong, Diane Chen, Diane Ehrensaft, Marco A. Hidalgo, Yee-Ming Chan, Robert Garofalo, Asa E. Radix, and Stephen M. Rosenthal.

This study is the result of a controversial, federally funded research effort called The Impact of Early Medical Treatment in Transgender Youth. The principal investigators are Olson-Kennedy, Garofalo, Chan, and Rosenthal. Launched in 2015, this is the most ambitious American attempt to gather data on minors who are medically transitioning.

While the $10 million or so given to this team by the National Institutes of Health has helped produce a small pile of published papers on a range of adjacent subjects, its core effort is the so-called Trans Youth Care Research Network, or TYC, which as Olson-Kennedy wrote in 2019 is “composed of four academic clinics providing care for transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) youth. The Network was formed to design and implement research studies to better understand physiologic and psychosocial outcomes of gender-affirming medical care among TGD youth.” Each of the principal investigators on the NIH project is at one of the four sites: Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles (Olson-Kennedy); Boston Children’s Hospital (Chan); Lurie Children’s Hospital (Garofalo); and UCSF (Rosenthal). The key feature of the TYC is an ongoing longitudinal study of kids who went through these clinics, and part of the plan, all along, has been to publish papers detailing their outcomes two years after starting puberty blockers (one subset of the cohort) and two years after cross-sex hormones (another).1

The Olson-Kennedy team’s most important paper to date, “Psychosocial Functioning in Transgender Youth after 2 Years of Hormones,” was published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2023 and lead-authored by Diane Chen of Lurie. In it, the team claimed that “In this 2-year study involving transgender and nonbinary youth, GAH [gender-affirming hormones] improved appearance congruence and psychosocial functioning.” (If you are already familiar with the controversy over this paper, you can skip down to “The New Preprint.”)

“Our results provide a strong scientific basis that gender-affirming care is crucial for the psychological well-being of our patients,” said Garofalo in a press release published by the hospital. The release was laden with other, similarly rosy quotes from other members of the team, including Olson-Kennedy.

After the study came out, I did a two-part deep dive into it, here and here, in which I argued that it suffered from serious flaws that make it almost impossible to extrapolate much of anything from it. If you’re interested in the innards of this debate, you should read those posts, but to briefly sum up the key issues:

—In Part 1 I explained that the authors preregistered one hypothesis about the outcomes of hormones on their study subjects, centered on one set of variables. Most of those variables disappeared in the NEJM paper with no explanation, as did the initial hypothesis, replaced by a new hypothesis and no variables of interest. This appears to be a rather straightforward case of what is known as “hypothesizing after the results are known,” or HARKing. HARKing allows a research team to come up with a hypothesis, find that that hypothesis is not supported by their data, change course midstream, dig around in the data, reverse-engineer a new hypothesis, and then present a different hypothesis as though that was what they had hypothesized all along. Because of well-known principles of statistics, that new result might be genuinely meaningless. (To oversimplify, imagine getting to throw as many darts as you want at a dartboard for as long as you want, removing the ones that didn’t get close to the bull’s-eye, and then calling your friends over to show how good you are at darts.)

—Even imagining away the HARKing problem, I noted in Part 2 that it was unclear how to interpret the new paper. To quote from my own summary of that piece, “1) The kids in this study had an alarmingly high suicide rate[,] 2) Most of the improvements the cohort experienced were small[,] 3) It’s impossible to attribute the improvements observed in this study to hormones rather than other forms of treatment that took place at these clinics [such as psychotherapy and/or medication for mental-health symptoms][,] 4) The one bigger improvement was in a variable that might not mean all that much[, and] 5) The researchers don’t even consider the possibility these treatments don’t work — their only answer is ‘more hormones.’ ” In addition, despite having a great deal of hidden flexibility to present the results in a favorable manner, the researchers couldn’t even claim they observed any improvement in the sample’s male-to-female transitioners — only the female-to-male cohort “improved” (if you could call it that), on average.

The publication of the NEJM paper was a jarring moment for me: Not just the fact that after all those years and all those dollars, that was the best the leading research team could do, but also that the journal itself allowed the study to be published in that form.

Everyone had been waiting for the Olson-Kennedy team’s study on puberty blockers for a long time. Among those who follow this subject, its delay had been the subject of a great deal of speculation. That controversy blew up last October, when Azeen Ghorayshi of The New York Times reported that Olson-Kennedy had told her, straightforwardly, that she was withholding the puberty blocker data for political reasons: “Puberty blockers did not lead to mental health improvements, she said, most likely because the children were already doing well when the study began,” explained Ghorayshi, and Olson-Kennedy said she was worried this finding would be weaponized in the current political client.

Now, seemingly a bit out of nowhere, we have a preprint of that study. I assume this has something to do with the Trump administration’s scrutiny of youth gender medicine providers and threats to their funding (which I wrote about in The New York Times here), but that’s just speculation.

“Mental and Emotional Health of Youth after 24 months of Gender-Affirming Medical Care Initiated with Pubertal Suppression” makes this claim in its abstract:

Ninety-four youth aged 8–16 years (mean=11.2 y) were predominately Non-Hispanic White (56%), early pubertal (86%) and assigned male at birth (52%). Depression symptoms, emotional health and CBCL [Child Behavior Checklist] constructs did not change significantly over 24 months. At no time points were the means of depression, emotional health or CBCL constructs in a clinically concerning range.

In other words, in the authors’ telling, these kids started out fine, and they ended up fine. Puberty blockers neither improved nor worsened their mental health, on average.

It’s important to recognize that this isn’t the final version of the paper — it is a preprint, which means that it hasn’t been peer-reviewed yet and we don’t know whether and in what form it will be published in a journal. Still, taken at face value, the new preprint suggests that the researchers are primed to recapitulate many of the problems with their NEJM study.

In any case, the publication of this preprint presents an opportunity. In a well-functioning peer-review system, the authors of a preprint will seek feedback, take that feedback into account, incorporate it into future drafts (alongside peer-reviewer feedback), and eventually publish a more polished paper in a journal than they might have otherwise. I like being able to critique a paper sitting in this space: While I’m not delusional and don’t think anything I write here will necessarily have any impact, it’s nice to be able to lay out specific critiques of a paper at a time when its authors can still do something meaningful in response.

And this paper has major problems. None of those problems, with one exception I’ll clearly mark as such, are nitpicky or particularly complicated or debatable. They all bear on the fundamental validity of this paper — whether, when it is published, we will be able to treat it as telling us anything meaningful about the effects of puberty blockers on the young people who are administered this medication. So it will be interesting to see how many of these issues, if any, are addressed between now and the final publication of the paper.

I’m going to run down the five issues I find most concerning in this preprint, plus a bonus sixth that may or may not be a fair criticism: potential HARKing; unexplained loss to follow-up; a boatload of unaccounted-for confounds; an introduction of more confusion about what puberty blockers are for (confusion that is now bordering on extreme and inexplicable;the potentially unjustified lumping together of kids from clinics that have different protocols and/or outcomes); and the possibility that the researchers used an inappropriate statistical technique.

In their preprint, Olson-Kennedy et al. write that “Specific study procedures are detailed elsewhere.[14]” The footnote leads to this 2019 protocol document, which explains that, for both cohorts, the team “will investigate the changes over time in gender dysphoria, depression, anxiety, trauma symptoms, self-injury, suicidality, body esteem, and quality of life.” (Multimedia Appendices 2 and 3 usefully list out all the variables the researchers planned to collect data on from the youth and their parents, respectively.)

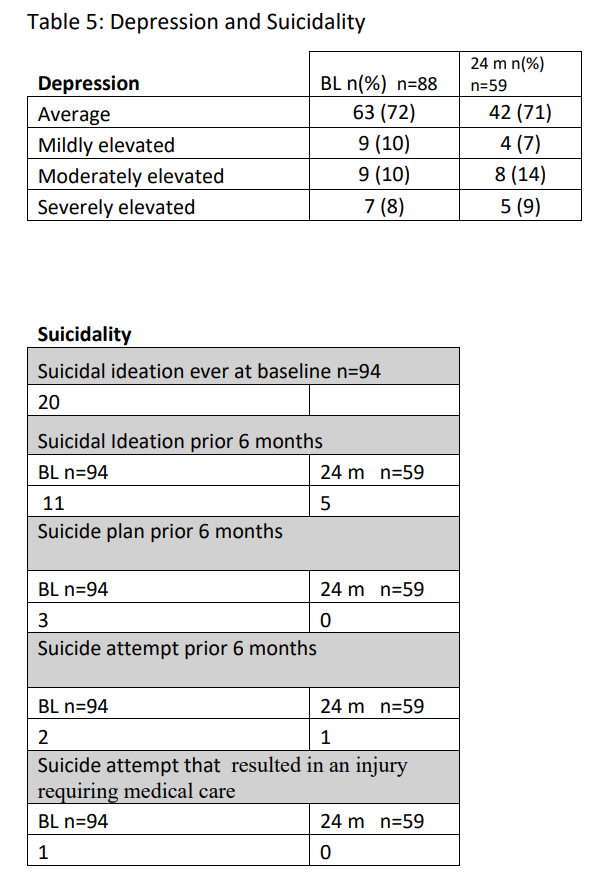

In the preprint itself, Olson-Kennedy et al. report outcome data on depression, a subset of scales from the NIH Toolbox Emotion Battery — Self-Efficacy, Friendship, Loneliness, Emotional Support, Perceived Hostility, and Perceived Rejection — and suicidality as well as the CBCL. These are all self-report items, with the exception of the final one, which is parent-report.

We have the exact same problem in this preprint as we did in the NEJM paper: The researchers changed from looking at one set of variables to another without offering any explanation why. That is, there’s very little overlap between the variables they said they were most interested in and the ones they ended up reporting outcome data on. Where’s the anxiety measure? The gender dysphoria measure? Social relationship and negative affect? The absence of the anxiety and body esteem data is particularly strange, given that those were two of the variables the team did choose to report on in their NEJM paper. There doesn’t appear to be any rhyme or reason to which variables get reported versus shunted off into a closet (or file drawer) somewhere.

This is a problem, because it gives Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues the freedom to dig around in the data in search of favorable trajectories and report those as though that’s what they had been looking for all along.

To be fair, there is at least one major methodological improvement here as compared to the NEJM study. The information on suicidality provided in the NEJM study was so threadbare as to be almost uninterpretable: “The most common adverse event was suicidal ideation (in 11 participants [3.5%]); death by suicide occurred in 2 participants.” “Suicidal ideation” means very little without further detail, since it encompasses a wide range of experiences (there’s a big and important difference between fleeting thoughts of suicide and more intrusive types of S/I, especially those which involve planning), and the authors provided no details whatsoever on the trajectory of these variables — on whether the kids on hormones became less suicidal over time — which is part of the whole point of this project!

In this latest preprint, at least, the authors report the sorts of more textured suicidality data that researchers favor, including whether youth had made a plan to end their lives and, if so, whether that had led to hospitalization.

Now, I don’t think it’s useful or realistic to argue that once a researcher preregisters a particular hypothesis, they must then lash themselves to the mast of that hypothesis for eternity, even as they are whipped around by their busy schedules, funding cuts, and the other inclement weather inherent to ambitious research efforts, ignoring the siren call of (reasonable) modifications to their study plan. But major modifications are far from ideal, and if researchers don’t firmly adhere to norms designed to fight HARKing, they need to at least explicitly justify deviations from those norms, or else there’s really no reason to trust their results. In this preprint, Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues continue their trend of not explaining why some variables disappear, replaced by others.

A hypothesis, in this sort of medical or social-science context, is a story about how the world might work. You’re saying, “I think that X might cause Y.” What I find disturbing is that Olson-Kennedy and her team have a tendency to change their story — significantly — midstream, and to then act as though the initial story no longer exists. The most straightforward explanation for this is that those earlier stories didn’t bear out, and now the team is trying to memory-hole them. There are other potential explanations, but the phenomena of file-drawering and outcome-switching are very well-understood, and are as good a starting assumption as any, especially in a case like this where the team will not publicly explain their work in any detail.

At baseline, there were 94 youth in this study. Two years later, the sample size had shrunk to 59, as noted in some of the results:

There are all sorts of conversations to be had about how much attrition is too much in a study like this, and what to do about it, most of them above my pay grade. But even we nonexperts can confidently say a few things here.

First, we know, because the authors say so, that kids were eligible for the study if they had a diagnosis of gender dysphoria and had begun blockers. This would have entailed a process involving both the young person and at least one parent. So, too, would have consenting to involvement in the study. So this isn’t a situation where you’re, like, surveying random people on the street, getting their number, and then following up months later. In a situation like that, it would be fair to expect a lot of people wouldn’t pick up the phone, or would be uninterested in answering any more questions.

Here, though, we’re talking about a group of families receiving specialty care at major gender clinics. They were enrolled between 2016 and 2019, according to the paper, meaning it was a period when the widespread expansion of youth gender medicine was getting ramped up, but there still wasn’t that much access to these treatments. Plus, once you’ve started your kid on treatment and have a relationship with a clinic, it stands to reason that you would be biased in favor of maintaining that relationship rather than starting over somewhere else (unless you had to move for work or something like that).

In light of that, it’s fair to ask whether this loss to follow-up rate here — 38% — is so high as to call the results into question. At the very least, it seriously hampers the authors’ ability to draw meaningful conclusions from this study. After all, if the kids who dropped out were significantly different from the kids who stayed in, which is a very reasonable assumption in light of the above, that could seriously skew the results.

Again, there’s a repeat performance aspect to what we’re seeing here. In their NEJM paper, the authors also had what appeared to be a high rate of loss to follow-up, and also didn’t address this issue at all (thanks again to the excellent and fastidious editors at NEJM, yes, snark intended). Here, they don’t even mention the issue, not even in the “Limitations” section. It should arguably be the first limitation! This is seriously first-semester stuff.

The data are the data, but the researchers could mitigate the damage here a bit in a couple of ways. First, they could report the result for the subset of kids who stayed in the study the whole time. They don’t. Second, they could explain how many of the families were truly lost to follow-up, in the sense they stopped coming to the clinic, versus how many continued to come to the clinic but stopped filling out the research forms. This is a massively important distinction. If a significant chunk of the 38% were truly lost to follow-up, that’s a very big deal — and useful information about the trajectories of kids who start on puberty blockers, because it would suggest a nontrivial number of them simply stopped taking hormones. If, on the other hand, most of that 38% were accounted for by the fact that filling out forms is boring and kids and their parents have other stuff going on — but were still coming to the clinic for their shots — that’s another matter entirely. Since the authors explicitly mention having access to medical records, they could likely make this distinction if they wanted to. They should.

The mean age of the study’s enrollees was 11.2 years old, but the range was 8 to 16. The authors don’t explain what they did with the older kids, who (one can assume) are much less likely to be on puberty blockers for two full years. This, too, could partially account for the seemingly high loss to follow-up, and it would be extremely useful to know what percentage of the total LTF can be attributed to this versus actual loss to follow-up versus continuing to come to the clinic and receive treatment, but declining to participate in the study anymore. One can only hope this is all explained more clearly in the final published paper.

This paper repeats a major problem with its NEJM predecessor: It makes no effort to control for access to psychotherapy, psychiatric meds, or both. I sometimes feel like I’m repeating myself, but with this sort of observational study, there’s absolutely no meaningful reason to attribute any trajectory, whether up or down or level, to youth gender medicine per se, rather than these other factors.

That would be bad enough on its own, but in this case things are even worse. The authors write that “Study limitations include that more than half of the participants had initiated gender-affirming hormones over the 24-month follow up period, limiting our ability to examine puberty suppression as monotherapy.”

Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues basically throw up their hands and don’t even try to examine the effects of PBs as monotherapy. This is kind of nuts!After all, the Dutch and the British have both published data on this (the latter after significant struggle and attempts not to publish it, which might sound familiar), that data conflicts, and it would be useful to have data from an American context, even if it’s from a deeply flawed observational study. Plus, as we’ll get to in a moment, Olson-Kennedy and her team have been claiming, for almost a decade, that PBs have a salutary effect as monotherapy.

I’m hoping the final product will be more precise and polished, because obviously Olson-Kennedy and her team have the data to report out the results for the subset of kids who did not start hormones during this period. Now, they will sacrifice a lot of statistical power, because losing “more than half” of a group of kids that has already dwindled to 59 by the final wave of data collection suggests something like n = 29 for the monotherapy group. That’s. . . not good. I wouldn’t necessarily blame the team, because doing federally funded research is inherently difficult and laden with bureaucratic obstacles, but it’s a decade later — a decade into a research effort that clearly stated, as one of its goals, to better understand the effects of PBs as monotherapy — and you have monotherapy data on a grand total of 29 kids or so? It seems like a major failure and wasted opportunity. And that’s assuming Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues even do break out those results. Something is wrong here.

There’s a whole, broader conversation here about the theory of the case for puberty blockers. As I’ve noted previously, Olson-Kennedy has jumped between different stories at different times. The original protocol for the Impact of Early Medical Treatment in Transgender Youth, published back in 2016, included this:

Hypothesis 1a: Patients treated with GnRH agonists [puberty blockers] will exhibit decreased symptoms of gender dysphoria, depression, anxiety, trauma symptoms, self-injury, and suicidality and increased body esteem and quality of life over time.

Then, last year, Olson-Kennedy put her name on a ridiculously error-riddled critique of the Cass Review that had this to say:

The Review’s implication that puberty-pausing medication should lead to a reduction in current gender dysphoria or improve one’s current body satisfaction indicates ignorance or misunderstanding at best, and intentional deception about the basic function of these medications at worst. In an era of abundant misinformation, it is important remember [sic] the exact function of these medications.

But wait — that statement came not too long after Olson-Kennedy had said this in a sworn expert statement from July 2023:

Over the course of my work in the past seventeen years with gender diverse and transgender youth, I have prescribed hormone suppression for over 350 patients. All of those patients have benefitted from putting their endogenous puberty process on pause, even the small handful who discontinued GnRH analogues and went through their endogenous puberty. Many of these young people were able to matriculate back into school environments, begin appropriate peer relationships, and participate meaningfully in therapy and family functions. Children who had contemplated or attempted suicide or self-harm (including cutting and burning) associated with monthly menstruation or the anxiety about their voice dropping were offered respite from those dark places of despair. GnRH analogues for puberty suppression are, in my opinion, a sentinel event in the history of transgender medicine, and have changed the landscape almost as much as the development of synthetic hormones.

So puberty blockers are “a sentinel event in the history of transgender medicine,” almost as important as hormones, and they turn lonely, isolated, homebound kids into healthy, much higher-functioning ones. Olson-Kennedy knows this from her personal experience — she has given blockers to 350 kids, and they all benefited from this medicine. She is batting 1.000. This is, statistically speaking, just about the most effective medicine in human history.

That’s one story.

Another story? Wait, what? We never said puberty blockers alone would help!

And arguably, the preprint constitutes a third story: The kids Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues at the other clinics were doing pretty well when they started, they were doing pretty well two years later, so the lack of noticeable changes isn’t really a knock on blockers. Also, 38% of them were lost to follow-up. (It’s unclear how Olson-Kennedy can be sure that all of the kids she prescribed hormones benefited from them when she doesn’t appear to be in contact with a significant chunk of them.)

Now, one way to square this circle is to point out that the ongoing study constitutes one subset of kids who were screened in certain ways, not the entire universe of kids Olson-Kennedy and her team put on blockers. So it could be that by dint of that screening, the kids in the federally funded study were doing well at baseline. This would raise further questions, such as why the team hypothesized there’d been improvement in a group that they had strong reason to suspect would come in with strong mental health in the first place, and (more importantly) why they haven’t ever addressed the fact that that hypothesis was apparently disproven, anywhere. But it would at least clarify things a little.

If this is the explanation, there’s another group of kids — more troubled ones — that are also getting blockers from Olson-Kennedy. These kids have incredible, life-changing improvement; improvement so profound that Olson-Kennedy believes, again, that she is batting 1.000. Olson-Kennedy just doesn’t have any data on these kids, or if she does she hasn’t published it.

This all gets pretty confusing. It’s obviously less than ideal that one of the leading youth gender medicine physicians and advocates in the country — and the recipient of millions in taxpayer dollars — can’t decide whether it is reasonable or outrageous to suggest that blockers, on their own, might be helpful.

It also raises obvious and practical on-the-ground questions about what, exactly, Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues are claiming to the patients and families in their care. Is the idea that if a deeply distressed child shows up at their clinics, puberty blockers could alleviate that distress? That was the hypothesis in 2016, and that’s what Olson-Kennedy said in 2023, under penalty of perjury, and there’s no meaningful evidence to support that claim. If the current preprint provides any evidence for anything, it’s something like If a kid who is already doing well goes on blockers, the blockers will keep them stable, when their situation might have otherwise worsened due to puberty.

I don’t think the preprint, as written, even shows that, for all the reasons I’m laying out in this article. Plus, recall that the authors believe, via their NEJM article, that they have shown that cross-sex hormones improve the mental health of these kids, and more than half of the kids in this sample also went on hormones! If hormones help, and most of these kids went on hormones, and the overall results were that the group stayed stable, wouldn’t that suggest blockers hurt?

I’m speculating because I have to. There is nothing here to latch onto; this preprint, in its current form, has so many problems and so many confusing aspects that it’s very fraught to attempt to extrapolate anything from it.

But back to the on-the-ground ramifications. Generally speaking, if a kid is doing well when it comes to X, you don’t give them a medical treatment to improve X. The argument for blockers now seems to be a bit more subtle: Even if a kid is doing well at the moment, puberty will make them distressed, and blockers can prevent that.

This isn’t a prima facie ridiculous argument. There are all sorts of medicines people take when they are well to help them stay well. But given the context here — young people whose parents or guardians are considering a treatment that will interrupt the natural process of puberty, with side- and long-term effects that aren’t fully understood — the difference between these two theories of the case (puberty blockers will resolve distress vs. puberty blockers will prevent future distress) is profoundly important. And it needs to be highlighted, bolded, underlined: If this preprint study, and the broader project Olson-Kennedy is co-leading, can only really speak to a subset of kids who started good and stayed good, that tells us very little about kids who seekblockers when they are already in significant distress (which has, for years, been an increasing percentage of the kids seeking care).

In their 2019 protocol document, Olson-Kennedy and some of her colleagues wrote “All four sites (i.e., Children’s Hospital Los Angeles/University of Southern California, Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard University, Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago/Northwestern University, and the Benioff Children’s Hospital/University of California San Francisco) employ similar models of care that include a multidisciplinary team of medical and mental health professionals and are considered the national leaders in the care of transgender children and adolescents.” I find it very unlikely that these different clinics are so similar that their samples can be lumped together.

Olson-Kennedy, for example, has long been an outspoken advocate against in-depth assessment and/or psychotherapy for kids considering going on puberty blockers or hormones. She views this as undue “gatekeeping” and believes that kids know who they are. My own most recent reporting on her and her clinic — a story for The Economist (click here if you hit a paywall) — about a girl who was immediately put on blockers with no meaningful assessment or psychotherapy, followed by testosterone, followed by surgery, and who now regrets her whole path — left no doubt that in some cases, at least, Olson-Kennedy practices what she preaches.

I seriously doubt all four clinics operate in such a laissez-faire manner. That’s not to imply they all do super careful, early Dutch-style assessment — according to Amy Tishelman’s testimony, for example, the assessment period at Boston Children’s had dwindled to a mere two hours as the clinic was flooded with patients, one with the young person and one with the parent(s) — but still: Is it actually a safe assumption to aggregate the kids at all four of these clinics? That’s what the investigators have been doing all along, and this brings with it the potentially serious problems that arise, statistically speaking, when you lump together unlike with unlike.

To resolve this, the authors, here and elsewhere, could present data showing that the clinics do actually operate in a similar manner and generate similar outcomes (if either condition is significantly violated, you can’t lump the way they are lumping): Do they have roughly similar attrition rates? Wait list lengths? Psychosocial outcomes? Assessment processes?

We don’t know any of this, and if there are significant differences in how the four clinics operate and/or in the outcomes they generate, that could be a major obstacle toward extracting anything meaningful from this project (including the NEJM paper, which also lumped) — at least unless and until the researchers break out their data by site.

Consider this a provisional, potential critique, far less solid than anything above.

If I’m understanding correctly, Olson-Kennedy et al.’s statistical analysis technique requires that the data they are missing be missing at random. They write that “The patterns of missing data were examined, employing Full Information Maximum Likelihood methods for the estimation of model parameters when data is missing at random,” with a footnote to this methods article. The article, in turn, distinguishes between “missing at random” and “missing completely at random,” and explains that the former is an acceptable level of randomness for some statistical techniques.

This is above my pay grade, but I did email a couple folks with more experience in quantitative stuff, and while neither gave a conclusive answer, both agreed with my general intuition that there might be a problem here. There is good reason to believe that the majority of the missing data, which comes from kids who dropped out of the study, is not missing at random, because those kids likely differed substantially from their peers who kept reporting data to the study.2

If I get a clearer answer on this, or find out more, I’ll update this section. Just something worth keeping an eye on if and when the final, peer-reviewed version of this paper is published, but probably not worth fixating on given all the other problems here.

***

It will be interesting to see how many of the above issues are addressed between now and when “Mental and Emotional Health of Youth after 24 months of Gender-Affirming Medical Care Initiated with Pubertal Suppression” is published in a peer-reviewed journal. Based on my recent experiences with researchers, editors, and journals in this field, consider me bearish.

It’s worth reiterating, though, that many of the critiques I have leveled at Olson-Kennedy and her team have only been levelable in the first place because there’s a paper trail — because in many cases, we know what they hypothesized and when. This is a prime example of how important practices like preregistration are. Given how opaque Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues have been in explaining their methodologies and answering follow-up questions, can you imagine how difficult the situation would be if we didn’t have access to these materials?

Thank you to the two anonymous experts who reviewed an earlier draft of this article and provided extremely useful feedback.

Questions? Comments? Inside information about the The Impact of Early Medical Treatment in Transgender Youth study? I’m at [email protected], or on X at @jessesingal. Photo: “Supporters of transgender youth demonstrate outside Children's Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) on February 6, 2025 in the wake of US President Donald Trump's executive order threatening to pull federal funding from healthcare providers who offer gender-affirming care to children. The hospital announced on February 4 it was pausing the initiation of hormonal therapy for "gender affirming care patients" under the age of 19 as they evaluate the Executive Order "to fully understand its implications." The announcement came after US President Donald Trump signed an executive order on January 28 to restrict gender transition procedures for minors. (Photo by Robyn Beck / AFP) (Photo by ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images)”