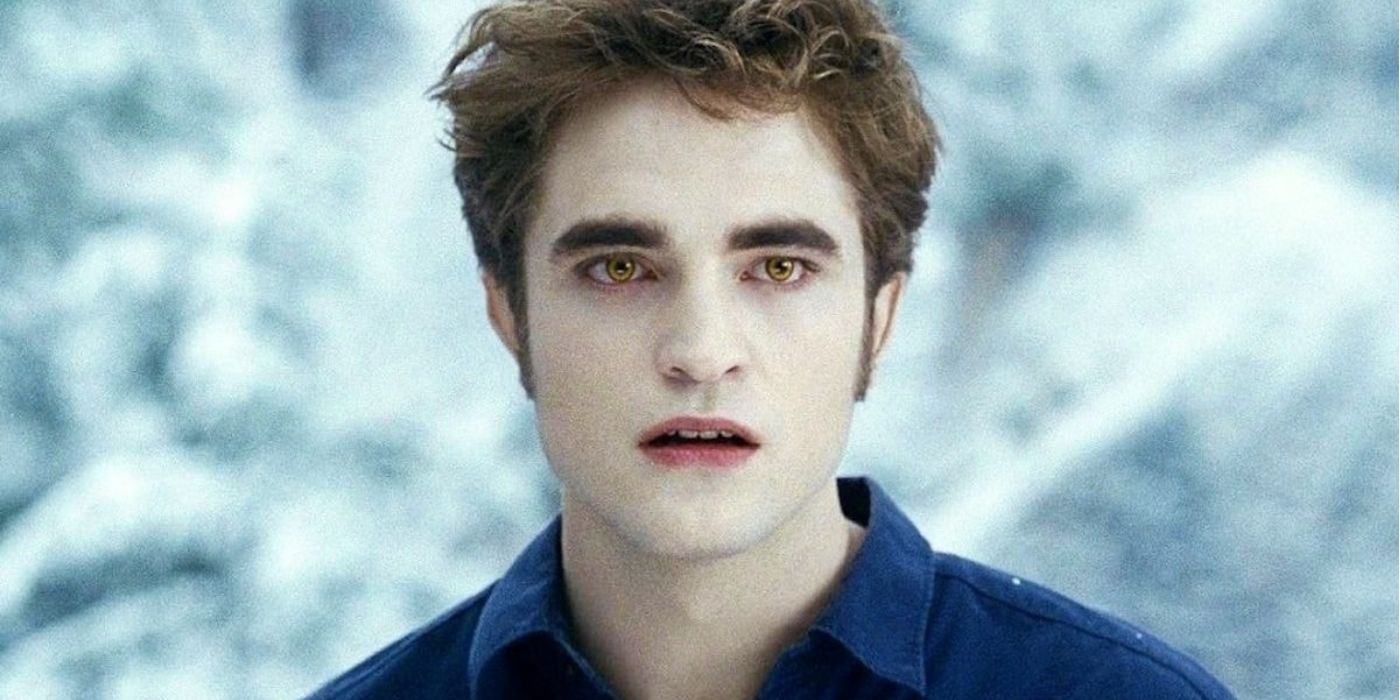

When Stephanie Meyer’s saga hit the literary world, it sparked a cultural phenomenon that took little time to transcend the pages and captivate audiences on the silver screen. From its debut in 2008 to its grand finale in 2012, the movies were a delight to watch, turning its cast into household names and redefining the vampire genre for a new generation.

Starring Kristen Stewart as the introspective Bella Swan, Robert Pattinson as the mysterious and brooding Edward Cullen, and Taylor Lautner as the fiercely loyal Jacob Black, the films brought Meyer’s best-selling novels and the intriguing supernatural romance to dramatic life. Across five films – Twilight, New Moon, Eclipse, and Breaking Dawn Parts 1 and 2 – the saga explored Bella’s journey from an ordinary teenager to a powerful vampire and how she braved love, danger, and the supernatural world.

Despite mixed critical reviews, the franchise amassed a devoted following and grossed over $3.3 billion worldwide. But like any book-to-movie adaptation, the Twilight films took creative liberties in their storytelling, making strategic changes to the source material to better suit the medium. Whether it was amplifying the central love triangle or tweaking character backstories, the movies reshaped Meyer’s books in ways that made the cinematic experience distinct.

Here is a breakdown of the 10 most drastic changes the Twilight movies made to the books.

In the Twilight movies, the Volturi are undeniably menacing, but their knack for violence is downplayed and dramatized for cinematic effect. The most infamous example is the battle sequence in Breaking Dawn – Part 2, where Aro rips Carlisle’s head off, and the Cullens suffer devastating losses, only for it to be revealed as Alice’s vision. The moment is a stark departure from the books, where the Volturi rely on manipulation and psychological warfare rather than outright slaughter.

Even in New Moon, the execution of a group of tourists is shown in chilling detail. Which is to say that the films lean on their villainous potential, making them feel more like traditional antagonists instead of a governing body with strict rules. The movies do not dive into the understanding of how the Volturi operate. They also don’t portray them as genuinely tortured immortals yearning for the release of death, arguably stripping away their nuances.

In the source material, Bella’s friends – Jessica, Mike, Angela, and Eric – are much more fleshed out, thus offering a richer glimpse into her human life before she fully immerses herself in the supernatural chaos surrounding her. Angela, for instance, is portrayed as the quiet friend who genuinely cares for Bella, whereas Jessica’s self-absorbed tendencies and her desire to climb the social ladder are more nuanced in the books. Mike Newton’s crush on Bella is persistent but not exaggerated. The friends are always present in Bella’s orbit; she spends a lot of time with them, and it feels organic.

The movies, however, condense their roles and reduce them to comic relief or background figures. Jessica, played wonderfully by Anna Kendrick, is given a snarkier personality, while Angela and Eric barely get any development arcs. The movies sideline Bella’s human friendships, depict her as a loner, and focus primarily on her interactions with Edward and the Cullens, which makes her transition into the vampire world less impactful.

One of the most iconic and visually striking moments in the Twilight movies is the transformation of the Quileute werewolves, or “shape-shifters,” as they are referred to in the books. In New Moon, Jacob’s first transformation is a dramatic, high-speed moment. He leaps into the air, and within seconds, his human form is replaced by a massive wolf. The transition is seamless, fluid, and designed for maximum cinematic impact.

The movies also focus on the sheer size and power of the wolves by showing them in slow-motion sequences or having Bella and other humans stand next to their imposing selves. In contrast, the transformation in the books is more grounded. It emphasizes werewolves as creatures bound by biology. The physical pain and emotional turmoil that comes with shifting forms, the heat, the trembling, the overwhelming sensation of change, leaves little room for the books to focus on the flashy part. The books also highlight the pack’s telepathic connection, which the movies barely touch upon.

Bella’s reckless motorcycle ride in New Moon is one of the most striking changes from the book to the movie. In the film, Bella sees ghostly visions of Edward whenever she puts herself in danger, which leads her to impulsively hop onto a stranger’s motorcycle and speed off down the street. This scene is chaotic, with Bella gripping the stranger as Edward’s spectral figure warns her to stop. The scene tries to visually represent Bella’s desperation and grief and leans into the idea that Bella is actively seeking means to feel close to him.

In the books, Bella’s dangerous behavior is more subtle. On her night out with Jessica, in Port Angeles, Bella spots a group of men with bad intentions, and as soon as she gets closer to them, Edward begins to speak to her. The book focuses more on her internal struggles and shows how she uses adrenaline to drown out her pain. The shift in the movies makes Bella’s heartbreak more external and dramatic.

Another core element of the Twilight saga is the complex and emotionally charged love triangle between Bella, Edward, and Jacob. In the books, Meyer’s words only reveal the truth and nuance of Bella’s feelings as she grapples with her love for Edward, which is unwavering, and her affection towards Jacob, the werewolf who becomes one of her closest friends. Her turmoil is more personal and subdued and limited to internal dialogue rather than external confrontations.

However, in the movie adaptations, the filmmakers chose to amplify the intensity and drama of this love triangle to create a more visceral viewing experience and have fans divide themselves up into Team Edward or Team Jacob. In Eclipse, Jacob’s kiss with Bella is framed as a pivotal moment, with Edward reacting in a way that heightens the rivalry between the two supernatural suitors. The films lean into Jacob’s desperation and aggression, which is obvious in scenes where he openly challenges Edward.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Edward Cullen’s backstory is his vigilante years, and they are completely omitted in the Twilight movies. In Stephenie Meyer’s Midnight Sun, it is revealed that Edward spent a period of his life hunting down criminals, using his vampire abilities to punish those he deemed morally corrupt. This phase in Edward’s life is important to understand where he comes from because it proves that he has darker instincts and it takes a lot of self-control for him to be near Bella.

Surprisingly, the Twilight movies completely skip this chapter of Edward’s history as a vampire, opting instead to focus on his brooding, self-loathing personality and his present-day relationship with Bella. While he’s still struggling to master his impulses, the omission makes Edward feel less layered. Had the movies chosen to offer fans a glimpse into Edward’s vigilante years, it would become obvious that his restraint wasn’t just about Bella, but a part of his larger journey of redemption.

Alice Cullen’s past is one of the most tragic backstories in the Twilight universe, and yet, the movies leave it out completely. In Meyer’s books, Alice was born Mary Alice Brandon in the early 1900s and had the ability to see glimpses of the future from a young age. After realizing that she had predicted her mother’s muder, her father sends her to an institution, where Alice endures horrific treatment. That’s when James, the tracker who later hunts Bella, sets his eyes on her and a vampire working at the asylum saves her from death by transforming her at the cost of his own life.

Both the movies and the books portray Alice as the psychic vampire who becomes a close friend and ally to Bella, which makes her an important character. And while the movie viewers are treated to the backstories of Carlisle, Rosalie, and Jasper, details of Alice’s life as a human are omitted completely. Her visions and her connection to James play a crucial role in the films, but her origins remain a mystery to movie audiences.

A neat and noticeable addition in the Twilight movies is the Cullen family crest, and it’s a detail that does not exist in the books. The films find each Cullen family member wearing the crest in different forms – Edward, Emmett, and Jasper sport it on cuff bracelets, Alice wears it on a thin choker and Rosalie on a necklace, Esme has it on a bracelet, while Carlisle wears it on a ring. The Cullens are supernatural beings and they’re not always with each other, but the crest symbolizes unity and reinforces their identity as a close-knit family.

The design also aligns with their vampire existence, with the lion, hand, and trefoil representing strength, faith, and eternity. It is a visual cue that helps establish them as a family. And while some fans feel it was unnecessary, it is a clever cinematic addition and it gives them a distinct visual identity on screen to make them stand out in a way that was not needed in the books.

Related

Every Movie in the Twilight Saga, Ranked by Rotten Tomatoes

With the Twilight Saga getting a much-needed TV series adaptation, interest has re-sparked for the popular vampire franchise.

Few moments in the Twilight movie franchise are as shocking, controversial, and talked-about as the way the filmmakers handled the climactic battle sequence in Breaking Dawn – Part 2. The film builds up to an intense confrontation between the Cullens and the Volturi, with major characters, including Carlisle and Jasper, meeting gruesome ends. The sequence is brutal, fast-paced, graphic, and emotionally devastating. However, just as the fight reaches its peak, it is revealed that the entire battle was just a vision shown by Alice to Aro and was meant to deter him from attacking. The twist was effective in subverting expectations, but it left fans feeling manipulated because they had to see their favorite characters die for no reason.

In contrast, the book’s version is less dramatic. In Breaking Dawn, the Cullens, their allies, and the Quileute wolves team up to convince the Volturi that Renesmee does not pose a threat to their secret existence. They also introduce Nahuel, a 150-year-old vampire-human hybrid, to prove their point. And because the Volturi’s primary goal is to protect their world and enforce rules, there is no battle at all, just a tense negotiation that ultimately ends with the Volturi retreating.

Bella’s lullaby is an iconic element of Twilight but the way it is presented in the movies differs significantly from the books. In the film, Edward plays a soft, melancholic piano piece for Bella, which is officially titled “Bella’s Lullaby” and is composed by Carter Burwell. The melody is gentle, haunting, and deeply romantic. The scene where he plays it for her in his room is intimate, and the movie uses this lullaby as a recurring reference by weaving it into key moments to demonstrate how strong their connection is.

The book handles the tune better than the movies because not only does Edward frequently hum it to Bella, but he also specifically mentions that he wrote it for her. In New Moon, he even puts it on a CD for her to listen to whenever. Of course, Meyer only uses words to describe the melody, so fans always speculated about what it might sound like and the movies created a tangible version of it. But it’s the book that describes it as a lullaby and makes it a symbol of Edward and Bella’s love.