When violins meet the didgeridoo

An ancient tree branch hollowed out by termites and a finely carved wooden violin—on the surface, they couldn’t be more different.

But in the hands of William Barton and Ghetto Classics, these instruments become one voice, telling a story of Australia’s and Kenya’s lands, spirit, and evolving identity.

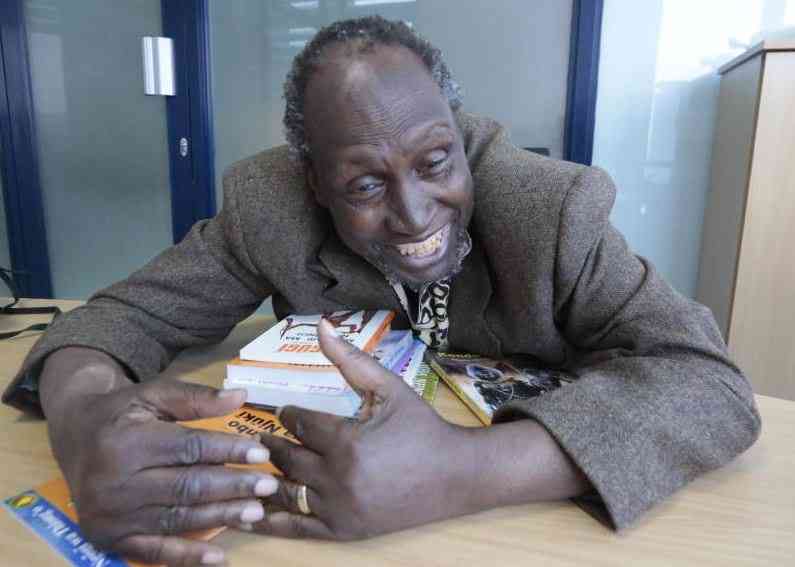

For celebrated musician Barton, the didgeridoo is more than an instrument— it’s a tool of storytelling and mimicry and an extension of his spirit. Barton opens up about the deep influences that have shaped his musical journey, starting with his greatest inspiration: his mother.

“It’s an instrument of imitation. You can even mimic the wind or a car going past,” he explains, before demonstrating how its sounds mimic kangaroos hopping, kookaburras laughing, and dingoes howling.

The didgeridoo is one of the world’s oldest wind instruments, originating with the Aboriginal people of Northern Australia.

It’s a long, cylindrical or slightly conical tube, usually about 1 to 1.5 metres in length, open at both ends. It’s traditionally made from termite-hollowed eucalyptus wood, though modern versions can be made from bamboo, PVC, or other materials.

The mouthpiece is often made of beeswax to make it comfortable to play. The sound of the Didgeridoo is described as deep, droning, rhythmic, and often hypnotic. It can be meditative, used in healing practices, and even in meditation classes.

Some sounds produced can resemble animal calls, drum beats, or electronic effects, all generated naturally by mouth and breathing techniques.

Whether played in the traditional context or as part of contemporary music, it continues to fascinate and resonate across cultures.

But Barton’s sound is anything but traditional. He weaves the ancient tones of the didgeridoo with the grandeur of opera, the earthiness of folk, and the raw edge of rock. “I grew up listening to everything. From classical to Led Zeppelin. It all fed into who I am as a musician,” he stated.

Barton’s inspiration comes from many places—the landscape, spiritual connection, family history, and the audiences he plays for.

“Music is my way of communicating with the world. I try to channel the stories of my ancestors, but I also let in the stories of today,” he says.

For him, the didgeridoo is more than a cultural symbol, but his voice, where he expresses love, grief, joy—everything.

He recently joined Kenyan artists, including the Ghetto Classics, on stage at the Kenya National Theatre, as part of celebrations marking 60 years of diplomatic ties between Australia and Kenya. It was yet another example of music’s power to connect cultures and bridge generations.

In Barton’s words: “Music is a universal language. And when the didgeridoo meets the violin, it’s not about blending genres—it’s about blending stories, spirits, and lands,” he stated.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Barton weighs in on the challenge with the freedom of the violin. “The elements of the violin and the didgeridoo both cross over rhythmically and harmoniously. If played in the right way and played with a certain sense of freedom,” she says.

Despite coming from different musical traditions, Barton and other artists find common ground in expression and emotion. “I guess it comes back to my mother playing classical music to me during my childhood,” Barton reflects.

“I found fascination in this otherworldly, old tradition of sounds from Europe… it takes you on a journey.”

Barton, born in outback Queensland, is one of Australia’s most acclaimed didgeridoo players. He learned the instrument from his uncle and embraced its cultural and spiritual power from an early age.

“Like any teenager, you listen to your ACDC and everything. But underlying all that was this other powerful, sort of mysterious, awe-inspiring sound—and that was the sound of my ancestors,” he recalls.

“She’s been my rock. She’s the reason I believe music has the power to heal, to connect,” he says, reflecting on the woman who first introduced him to the rhythms and traditions of his culture.

He began playing the violin at a tender age while in primary school. Classically trained, he has performed with orchestras across Australia and Europe. Yet, his curiosity led him beyond tradition:

“I draw on all the classical knowledge that I have… but these days I like to do it as much as possible with all different kinds of artists.”

“It’s about the nationalistic heartland, your mother country. You know, you’re singing up the land, you’re singing up elements that empower you,” he says.

Playing the didgeridoo involves several unique techniques:

Buzzing the lips (The Drone): The core sound of the didgeridoo is called the drone. This is made by buzzing the lips into the instrument, similar to how brass players create sound.

It produces a single, deep, resonant pitch — but within that tone are many subtle variations and overtones.

Vocal and mouth modulations, where tongue movements and mouth shape create different vowel sounds, alter the texture of the drone.

Voice can be added to the drone to create harmonics or imitate sounds like animals or environmental effects.

Animal imitation (Traditional Style): Traditional Aboriginal players often imitate animal sounds like kangaroos or kookaburras. These sounds are used to tell stories and represent the natural world in ceremonial music.

Circular Breathing is a signature technique of didgeridoo playing. It allows the player to produce a continuous sound without stopping for breath.

The player fills their cheeks with air, uses the cheeks to push air through the instrument while quickly inhaling through the nose.

This technique enables continuous play, sometimes lasting for minutes or even hours.

It also has health benefits, such as improving airway function and helping manage sleep.