BMC Infectious Diseases volume 25, Article number: 856 (2025) Cite this article

AbstractSection Introduction

The WHO’s 2024 Global tuberculosis (TB) Report shows that TB causes 1.25 million deaths annually, including 161,000 TB-Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infections. It affects 10.6 million people, mainly in Asia and Africa, 75% of whom are in the economically active age group of 15–54 years. Treatment interruptions hinder efforts to eliminate TB by 2030. According to a recent systematic review conducted using Ethiopian studies indicated that the pooled prevalence of TB treatment cure rate was 33.9%. There is a lack of evidence on time to TB treatment cure in Ethiopia using survival analysis.

AbstractSection Objective

This study aimed to determine the time to TB treatment cure and its predictors among TB patients from January 2021 to December 2023 at public health facilities in Arba Minch town. South Ethiopia.

AbstractSection Method

An institution-based retrospective cohort study was conducted among 628 selected TB patients who were admitted to the TB care unit at Arba Minch General Hospital, Dilfana Primary Hospital, and both health centers from 2021 to 2023. A Kaplan Meier survival curve was fitted to test the survival time. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify predictors with TB treatment cure. Significance was considered at a p value ≤ 0.05 with an adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) 95% CI in the multivariate analysis.

AbstractSection Results

Out of the 628 patients whose records were analyzed, the median time to cure was 162 days. The significant predictors of time to TB cure included being male (AHR 0.3, 95% CI: 0.35–0.95), history of TB treatment (AHR 0.56, 95% CI: 0.35–0.95), normal BMI (AHR 1.04, 95% CI: 1.32–1.49) and attending at secondary heath facility (AHR 1.69, 95% CI: 1.40–2.00).

AbstractSection Conclusions

Socio-demographic and clinical related factors were found to be independent predictors of time to cure. TB control programs should adopt gender-sensitive approaches to address delayed cure in male patients, integrate nutritional assessment into care and strengthen primary health facilities.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis that mostly affects the lungs [1]. According to the 2024 Global TB report, significant advancements have been made in the fight against TB across Africa [1]. According to the WHO consolidated guideline on TB, the essential anti-TB drugs are isoniazide, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol [2]. The first-line treatment for TB in Ethiopia is rifampicin (R), ethambutol (E), isoniazid (H) and pyrazinamide (Z). Drugs are available in fixed-dose combinations [3]. The treatment of TB has two phases: intensive (initial) and continuation. TB medications are often self-administered by the patient, and they must collect their drugs monthly from a healthcare facility [3].

In the Global TB Report of 2024 by the World Health Organization (WHO), 1.25 million people died from TB globally [4]. A total of 10.6 million individuals worldwide are expected to have contracted TB, with the bulk of those cases occurring in the WHO Regions of Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Western Pacific [4].

In Africa, almost 2.5 million individuals contracted TB in 2022 [5]. According a systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the pooled cure rate was 64.5% (95% CI 55.1–73.3%) which was obtained from 14 studies in Sub-Saharan Africa [6]. Among the 10,156 smear-positive PTB patients evaluated on directly observed therapies (DOTs) in North Central Nigeria, 20.1% were cured at the end of treatment [7]. Another study in Nigeria reported treatment cure rates of 61.5% in patients under facility-based DOTs [8]. A retrospective follow study conducted in Ghana revealed that the cure rate of TB patients was 30.7% [9].

Ethiopia made significant progress in reducing the incidence of TB, according to the 2024 Global TB Report by the WHO. However, the country continues to have a high total incidence of TB 146 per 100,000 people [10]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of studies conducted in Ethiopia reported a pooled TB treatment cure rate of 19.3% (95% CI: 14.0–24.0%) [11]. Retrospective follow-up studies conducted in different regions of Ethiopia have reported variable cure rates: 85.5% in the Tigray region [12], 33.7% in Eastern Ethiopia [13], 27.5% in Southern Ethiopia [14], and 12.6% in Northwestern Ethiopia [15].

The majority of studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, including those from Ethiopia [6,7,8,9, 11,12,13,14,15], have not assessed the time to TB treatment cure using survival analysis, limiting insights into the temporal dynamics of recovery. To reach global target of treatment success rate of at least 90% for all forms of TB by 2035 [16], evaluating time to TB treatment cure is essential for assessing the efficacy of treatment interventions and ensuring the best possible patient outcomes. Our findings are critical for reducing the impact of TB by identifying potential predictors that influence the time to TB treatment cure. Therefore, our study aimed to determine time to TB treatment cure and its predictors among TB patients in all public health facilities in Arba Minch Town for the period from January 2021 to December 2023.

Arba Minch town is the capital town of the Gamo zone. It is located 505 kms from Addis Ababa (capital city of Ethiopia). The town is one of the lowlands in southern Ethiopia and has a hot climate with an average temperature of 29 °C and annual mean rainfall of 900 mm. The town has 2 subdivisions: Secha and Sikela, each 5 kms apart, and the town has a total population of 125,411. There are four public health facilities in the town: Arba Minch General Hospital, Dilfana Primary Hospital, Secha Health Center and Woze Health Center. The facilities serve more than four million people in Arba Minch town and neighboring zones. All facilities provide TB treatment services. The study included TB registrations from January 1, 2021, to December 30, 2023.

A facility-based retrospective cohort study design was conducted among adult TB patients aged 18 years and older, who were registered in the TB logbook. The source population consisted of TB patients who initiated treatment at public health facilities. The study population included TB patients who were bacteriologically positive using Gene Xpert registered in the TB logbook at Arba Minch General Hospital, Dilfana Primary Hospital, Secha Health Center and Woze Health Center from January 2021 to December 2023.

Health facilities in Ethiopia adhere to the implementation guideline for GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay to standardize and optimize the use of GeneXpert technology within the National Tuberculosis (TB) Control Program [17].

Patients were excluded if they had incomplete medical records for at least one variable, were transferred to or from other healthcare facilities, were children, pregnant women, individuals with any drug-resistant, or had extra-pulmonary TB.

The sample size was determined via two population proportion formulas via the Epi info version 7 software by considering the following assumptions: 95% confidence interval (CI), power 80%, ratio of unexposed to exposed 1:1, and parameters: outcome in exposed (sex client female) = 89.7%, outcome in unexposed (sex client male) = 72.9% [18], and adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.8. Accordingly, the calculated sample size for this study was 628 (Table 1).

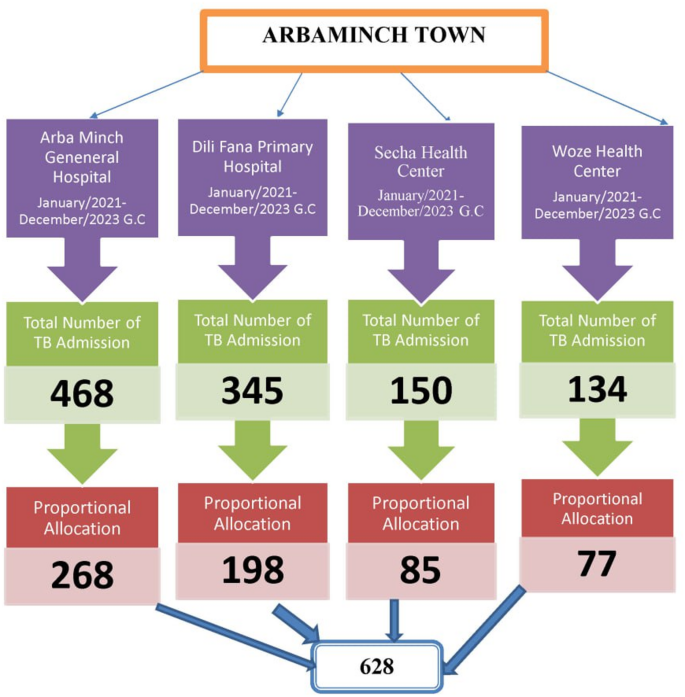

TB patients were selected from the four health facilities using proportional allocation based on the number of patients registered in each facility’s TB logbook. Specifically, 268 patients were from Arba Minch.

General Hospital, 198 patients from Dilifana primary hospital, 85 patients from Secha Health Center, and 77 patients from Sikela Health Center. In this study, we employed a simple random sampling technique to recruit a predetermined sample size via the registration/card numbers of the enrolled clients. Computer-generated random numbers were utilized to select study participants’ records from each consecutive year. From a total of 1097 TB patient records collected between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2023, 628 samples were selected (Fig. 1).

Schematic presentation of sampling procedure for a study on treatment cure and predictors among tuberculosis patients in Arbaminch Town, South Ethiopia: A retrospective cohort study in 2024

The source of data is individual patient record documents, including register monitoring cards and patient folders. Data were collected via a structured checklist or questionnaire that was based on previous study [12]. KoBoToolbox was used to create forms and collect data offline via mobile devices.

The checklist included information on socio-demographic characteristics (age and sex), clinical and treatment-related variables (including history of treatment— new or previous history — and TB/HIV co-infection status, weight, height, BMI), HIV status, and treatment outcomes (cured, treatment completed, treatment failure, default, died, or transferred out). Data collection forms and appropriate modifications concerning this study were made. This is prepared in English. Data were collected by six diploma-level health professionals trained in clinical nursing, under the supervision of two BSc-level health professionals qualified as health officers.

A one-day training session was provided to the data collectors by the principal investigator, covering the study objectives, participant selection procedures, confidentiality protocols, questionnaire content, data collection procedures, and data quality assurance measures. Each day following data collection, completed questionnaires were reviewed for completeness by the supervisor and the principal investigator, and feedback was provided to the data collectors the following day.

Data quality was assured by careful design of the data extraction formats, appropriate modifications, appropriate recruitment, and adequate training and follow-up for the data collectors and supervisors. The pretest was performed on 5% of the population (n = 31) at Arba Minch General Hospital (n = 23) and Dil Fana Primary Hospital (n = 8). The principal investigator and supervisor provided intensive supervision during the entire period of data collection. The principal investigator reviewed a random sample of registration forms to confirm the reliability of the data before data collection, and the investigators also made random cross-checks for completeness, accuracy, and consistency at the end of each day, corrective discussion was undertaken with all the research team members. During the morning hours, remarks were made regarding the techniques that can be utilized to remove or limit errors and to take remedial steps. The data were checked for completeness and consistency.

After data collection, the data were downloaded from the KoBoToolbox in Excel format. Exported to STATA version 17 for analysis and data management, the data were then investigated to assess the extent of missing values, identify notable outliers, examine multicollinearity, evaluate normality, and determine the proportionality of hazards over time. Graphical and statistical methods such as the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test were applied to check the normality of the data. The Cox regression model for its fitness to the data and its adequacy was checked by graphing residual plots such as the Cox-Snell residual.

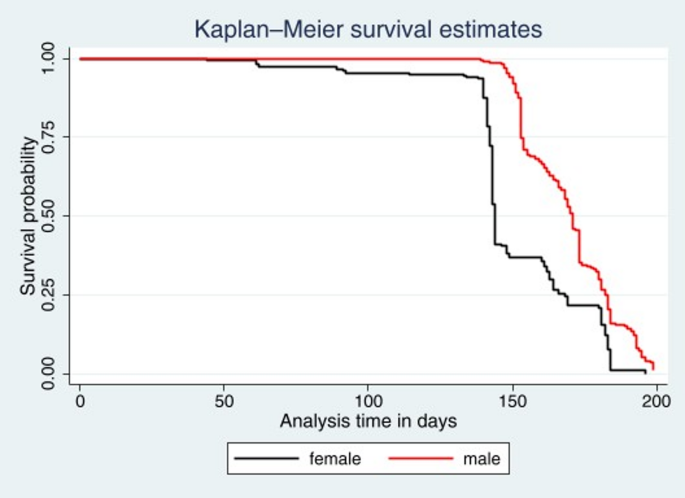

A Kaplan–Meier survival curve together with the log-rank test was fitted to test the survival time of patients receiving TB treatment. Variables significant at the p < or equal to 0.25 level in the bivariate analysis, and biological plausibility were considered and included in the final Cox regression analysis to identify independent predictors of TB treatment cure. The crude hazard ratio (CHR), AHR, 95% CI, and P-value were used to assess the strength of the associations and their statistical significance. Covariates were checked for interaction effects. The data are presented in the text, tables, and figures.

The study included a total of 628 TB patients. The mean age of the TB patients was 36.24 (± 5.7) years. More than two-third of patients (73.89%) were aged between 25 and 64 years, followed by those aged 15 to 24 years (16.40%) and those aged 65 years or older (9.71%). The sex distribution revealed that more male patients (54.14%) than female patients (45.86%) were included in the study population. Most of the patients were treated at primary health facilities (57.32%)The average weight of the patients was 59.96 kg (± 10.9), and the average height was 1.65 m (± 0.8), with varying BMI values. Most of the patients (78.03%) had a normal BMI, whereas 12.58% and 9.39% were overweight and underweight, respectively. The great majority of the patients (94.27%) were new cases of TB. Comorbidities were rare; only 1.76% of the patients were HIV positive and the other 98.25% were HIV negative (Table 2).

Out of the total patients, 89.80% were successfully cured. A small portion of patients experienced death (1.27%) or became lost to follow-up (2.23%). Transfer out cases, accounted for 5.43%, while retreatment was observed in 1.27% of the cases (Table 3).

The median survival time was 162 (95% CI: 158, 164) days, and the multicollinearity of the covariates in this study was measured by the variance inflation factor (VIF), which was 1.21. The time to cure TB was influenced by several key factors, including the type of healthcare facility, the patient’s sex, the HIV status, and the treatment history. Patients treated in secondary health centers had a greater hazard of cure than did those treated in primary health centers, with an AHR of 1.69 (95% CI: 1.4, 2.00). The hazard of cure was 70% lower for male patients than for female patients (AHR = 0.3 (95% CI: 0.29, 0.433)). Compared with HIV-negative patients, patients without HIV had a greater hazard of cure but no statistically significant hazard of cure (AHR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.4, 2.39).

The hazard of cure was 44% lower for patients with a history of previous TB treatment than for new patients (AHR = 0.56 (95% CI: 0.35, 0.96)). A one-unit increase in weight increases the hazard of cure by 2% (95% CI: 1.01, 1.03). Patients with a normal BMI had a slightly greater hazard ratio for being cured than underweight patients did. The AHR of 1.04 indicates that, after adjusting for other variables, the hazard of being cured for normal weight patients is 4% greater than that for underweight patients (Table 4).

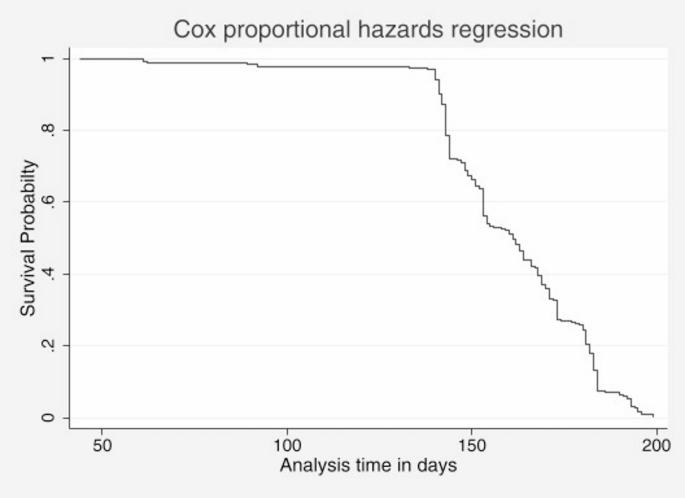

On the basis of the Kaplan‒Meier survival estimates, female patients are more likely to be cured than male patients (Fig. 2). The Cox proportional hazards regression plot in Fig. 3 presents the time to cure TB such that the survival probability begins at 1 (all patients ill) and decreases over time as patients are cured. In the beginning, after approximately 50 days, the survival curve is relatively flat, which means that few patients are cured at the beginning. There is a steep curve between 50 and 150 days, which means that there is a significant increase in the number of patients cured during this critical treatment phase. After 150 days, the curve continues to decline at a slower pace, which means that most patients have been cured, and by approximately 200 days, all patients have been cured. Thus, the plot demonstrated that the majority of patients achieved a cure between 50 and 150 days, with almost all patients cured by 200 days (Fig. 3).

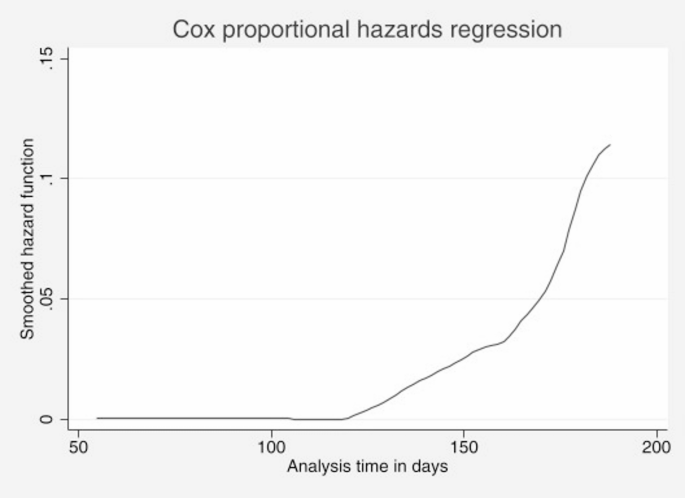

The Cox proportional hazards regression plot with the smoothed hazard function provides insight into the risk of being cured of TB over time. The Y-axis represents the smoothed hazard function, which indicates the instantaneous rate at which patients are cured, whereas the X-axis represents the analysis time in days. After 150 days, the hazard function increases sharply, indicating a significant increase in the rate at which patients are cured. This steep increase suggests that most patients achieve a cure during this period (Fig. 4).

This study aimed to evaluate the time to cure status and predictors influencing the cure rate of TB patients admitted to public health facilities in Arba Minch town from 2021 to 2023. The median survival time in this study was 162 days, which is comparable to that reported in a similar study conducted in Mezan, Southwest Ethiopia, which reported a survival range of 156–180 days [20]. Differences in the study setting may account for the variations observed. The cure rate in our study was 89.80%. Our study cure rate was comparable with the WHO recommended standard of 90%, indicating that TB care services in our study area meet international performance benchmarks [16].

The study also indicated that the majority of cures occurred in secondary health facilities rather than primary health facilities. This observation can be attributed to Ethiopia’s tiered healthcare system, which is structured into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, each with distinct roles in delivering healthcare services. Primary health facilities, including health posts and centers, focus on preventive, promotive, and basic curative services and are designed to be accessible to rural populations [21, 22]. In contrast, secondary health facilities provide more specialized care, including surgical procedures and inpatient care for serious illnesses, and typically cater to patients referred from primary facilities.

Compared with males, females exhibit better survival outcomes. A study conducted in Europe revealed that men are significantly more likely to die from TB than women are [23]. This disparity could be linked to the greater likelihood of men having comorbid conditions such as smoking-related illnesses or other chronic diseases that complicate TB treatment and worsen survival outcomes. Studies indicate higher on-treatment mortality rates for male patients due to these additional health challenges [24].

Patients with a history of previous TB treatment had poorer survival outcomes than those who were receiving treatment for the first time. Research shows that previously treated patients face a significantly greater risk of adverse outcomes, including lower treatment success rates and higher rates of complications [25].

Underweight patients account for a significant proportion of TB cases because several interrelated factors impair their immune response and increase susceptibility to the disease. Research indicates that individuals with a BMI less than 18.5 are at markedly greater risk for developing TB, as underweight status is associated with compromised immune function. For example, a study reported that the risk of TB incidence increased with increasing severity of underweight, with AHR indicating that individuals with mild, moderate, and severe thinness had 1.98, 2.50, and 2.83 times greater risks of developing TB, respectively, than individuals with normal weight [26, 27].

Weight has been shown to be significantly associated with treatment outcomes in TB patients, with higher weight correlating with improved cure rates. Similarly, a study conducted in Northwest Ethiopia revealed that patients who gained weight during TB treatment had better outcomes [28]. This is because proper nutrition strengthens the immune system, which is crucial for fighting infections.

These findings provide valuable insights into the factors influencing TB treatment outcomes in Arba Minch and underscore the importance of addressing specific patient needs and healthcare system structures to improve survival rates and overall treatment success.

The study’s retrospective cohort design led to the exclusion of several important variables, such as socio-demographic and socioeconomic factors, including dietary intake, wealth status, educational level, and distance to healthcare facilities. Therefore, the independent influences of these variables on time to cure were not examined. Additionally, this study focused exclusively on pulmonary tuberculosis, and therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to patients with extra pulmonary TB. Furthermore, bacteriologically positive patients were identified using the GeneXpert assay; however, culture results were not considered in this study. Although GeneXpert is highly sensitive, it may fail to detect TB in cases with very low bacterial loads, such as in some pediatric or extrapulmonary cases. Additionally, it only detects rifampicin resistance and cannot identify resistance to other TB drugs. Smear microscopy for follow-up is limited by its inability to differentiate live from dead bacilli, lacks drug resistance detection, is operator-dependent, and has low sensitivity in low bacterial load cases.

In conclusion, Socio-demographic and clinical related factors were found to be independent predictors of time to cure. The median recovery time was 162 days. TB control programs should adopt gender-sensitive approaches to address prolonged time to cure in male patients. Nutritional assessment should be integrated into care, as increased weight is linked to fast time to cure and strengthening primary health facilities through capacity building and resource allocation is essential.

The datasets of the study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

First, I would like to express my thanks to Arba Minch University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Graduate Studies, for giving me this chance and support to prepare this thesis and for funding. Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisors Mesfin Kote and Eshetu Zerihun for their assistance, constructive comments, and suggestions for developing this and for funding. My sincere thanks also go to all staff members of the TB care unit of Arba Minch General Hospital, Arba Minch Dil Fana Primary Hospital, and both health centers for their cooperation in data collection. I would like to extend my appreciation to the Arba Minch University, College of Health and Medical Science Librarian and Internet center coordinator for their support and assistance in obtaining the literature materials.Last, but not least, my deepest gratitude goes to my family that has been a source of pride and courage throughout my work, for giving me constructive ideas, encouragement, and motivation during my studies.

The current study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. An ethical clearance letter was obtained from Arba Minch University’s institutional review board (Protocol No.: DD23258). Prior to data collection, the administrations of Arba Minch General Hospital, Dil Fana Primary Hospital, Secha Health Center and Woze Health Center were informed about the study objectives and procedures. Permission for the study was obtained from the hospital administrations. The Arba Minch University’s institutional review board has approved the waiver of informed consent to participate in the study. As the study was based on TB registration (secondary data), no consent was needed to obtain from the study participants. Upon completion of data collection, the records were returned to the registry and stored on the designated shelves without disrupting the routine operations of the center. The data collection forms did not include any personally identifiable information, such as patient names, addresses, telephone numbers, or the names of the healthcare providers. Additionally, confidentiality was maintained by using anonymous tool and ensuring that all data were securely stored.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Zeruma, D.D., Kote, M., Zerihun, E. et al. Time to a tuberculosis treatment cure and its predictors among tuberculosis patients at public health facilities in Arba minch town, South Ethiopia: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 25, 856 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-025-11224-7