They were imprisoned, pregnant, and alone. Then someone spoke for them

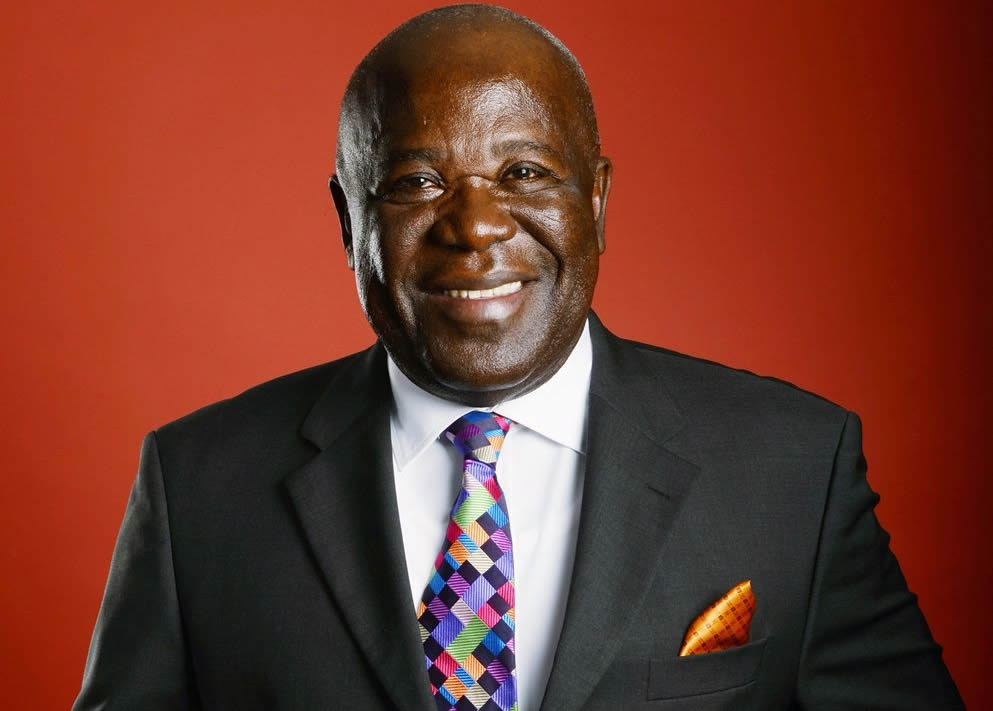

Image Description: The silhouette of a pregnant woman standing behind dark, rusted prison bars inside a dim stone cell. The silhouette is filled with clouds, galaxies and birds that appear to fly out from within her.

Lagos, Nigeria (Minority Africa) — Fausat Olayonu* was heavily pregnant when she and her friend were arrested by the police in October 2023 in Abeokuta, Southwest Nigeria, for stealing a radio set worth N20,000. When her case was called in court, she had no legal representation and had resigned to the fate that her unborn child would be delivered inside the rat-infested prison.

Fortunately for her, a lawyer from the mobile office of the Headfort Foundation for Justice in the region stepped in to represent her during the trial. Every month, the organisation’s lawyers pay advocacy visits to various prisons, interacting with inmates to hear their stories. It was during one such visit that they met Olayonu.

“I took the radio set because my boss, who is the complainant [in the case], refused to pay my salary for three months,” she admitted.

Although the court found her guilty of stealing the radio set, she was allowed to go home, at least to receive maternity care due to her pregnancy, which made her happy. Her friend, who knew nothing about the offence, was discharged and acquitted, but not before spending nearly two months in jail.

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous democracy, grapples with a slow justice delivery system, where citizens are sometimes arbitrarily detained for petty offences. Many problems underpin this tragic situation: police brutality, corruption, and overcrowded prisons. Over 79% of inmates in Nigerian prisons are awaiting trial—many have not been convicted in the law courts.

This is true even in the face of legal frameworks such as the Administration of Criminal Justice Act (ACJA) 2015, which mandates timely trials to prevent prolonged detention and prison congestion.

In Nigeria, high courts and judges preside over criminal cases. As in the UK, minor offences are handled by magistrates, while serious offences are referred to the high courts. Sadly, it may take years to receive a referral, meaning suspects can remain in detention longer than the sentence for the alleged crime.

Unlawful detention has led to detainees languishing in limbo, sometimes contracting communicable diseases, or even dying.

Established in 2019, the Headfort Foundation for Justice seeks to reform Nigeria’s justice system and advocate for marginalised women by building formidable relationships with government agencies, human rights institutions, and concerned stakeholders.

To change the narrative around prison congestion and the snail pace of justice, the organisation operates mobile offices in court premises across different states, offering accessible pro bono legal services.

Its all-female team launched the LawyersNowNow project, an app designed to provide immediate legal support to vulnerable individuals facing legal challenges, especially human rights violations.

Since its inception, the foundation has secured the release of 634 indigent and wrongfully accused Nigerians, with the app contributing significantly to many of these cases. It further solidifies the transformative potential of technology in access to justice.

“We introduced the LawyersNowNow App in an effort to minimise this timeframe and prevent human rights violations in Nigeria,” Oluwakemi Adenekan, the project manager, told Minority Africa. “This innovative platform swiftly connects victims of human rights abuses with human rights lawyers within a minute, ensuring rapid access to legal representation. So far, we have 1,865 users and have resolved 234 legal issues resolved through this application.”

Adenekan added that the foundation is important in a country like Nigeria, where “many poor victims of violations of human rights become entangled in the legal system and are unable to hire lawyers [for defence] advocates due to their financial situation. These people don’t often get their fair share of justice.”

The foundation also conducts community outreach and legal education programmes to empower individuals with knowledge of their rights and the tools to advocate for themselves.

In 2023, Vee Adebiyi*, then 26 years old, was working as a sales representative for a Nigerian fintech startup. Part of her job involved processing loans for point-of-sale (POS) operators.

Two of the operators she worked with took out a loan totalling about one million naira. One of them repaid only a tiny fraction before disappearing, along with the POS machine, without a trace.

At the time, Vee was pregnant. She was immediately fired from her job, and her employer had her detained at a police station in Alausa, Lagos State. She spent a week in custody before being taken to court, and ultimately, she spent six months in prison before she was finally granted legal reprieve.

She remembers the crushing helplessness she felt, especially knowing she was carrying a child.

“Imagine when I wanted to work for the loan shark, they promised that I won’t regret it, but it’s all a whopper,” she said. “They forced me into repaying all the loans of the defaulter, and I had to approach the Headfort Foundation in June 2023 for legal aid when I could no longer pay the lawyer I hired.”

In an interview with Minority Africa, Oluyemi Orija, founder of the Headfort Foundation for Justice, said that the inspiration behind the organisation traces back to a defining moment from her childhood.

“It was in the year 2000 when I was just 12 years old,” she recalled. “A tragedy unfolded in my village, where over 20 breadwinners of homes were arrested and detained for having farms in close proximity to the scene of a crime. Many of these individuals were known to me, some even related in one way or another.

“I vividly remember the confusion and distress that engulfed the community as we grappled with the unjust detention of these individuals. When I questioned my father about why they weren’t released, he explained that legal representation was needed, but the community couldn’t afford lawyers from the state capital at the time.”

Years later, after becoming a lawyer in 2013, she witnessed a recurring pattern reminiscent of that fateful incident in her childhood—people dragged to court on frivolous charges and unjustly detained, perpetuating a cycle of suffering for families.

“Understanding the devastating impact of incarceration, especially on children and families, I founded the organisation to provide legal representation to those who couldn’t afford it to have freedom at ease.”

Orija said limited access to legal resources and information, particularly among marginalised communities unaware of their rights, poses a challenge to their work. “This lack of access hinders individuals from seeking legal assistance when they face injustice, and they have made decisions that have negatively impacted their cases before they encounter us,” she explained.

She also cited financial constraints and systemic inefficiencies, such as case backlogs and procedural delays, which often lead to prolonged pretrial detention. Emphasising the need for public support, Orija said these delays “exacerbate the suffering of those detained and undermine their right to a fair and timely trial.”

In March 2024, Nigerian authorities announced efforts to reduce delays in the justice system and simplify bail conditions to decongest the country’s 244 correctional centres. Vee, now free from the clutches of incarceration, said: “I’m very grateful that the organisation came to my rescue. The whole ordeal gave a terrible blow to my old father, who struggled hard to raise parts of the loans I was forced to pay.”

*Names have been redacted to protect the identity of sources.

Edited/Reviewed by PK Cross, Awom Kenneth, Caleb Okereke, and Uzoma Ihejirika.

Illustrated by Rex Opara.