The Unsung Artist Behind 'The Snowman'

(And a very special welcome to our 40,000th subscriber, who joined us this week.) We’re back with a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter.

Today’s lead story is exciting. With the help of journalist Andrew Osmond (Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist), we’re diving into the life and art of Dianne Jackson — the underappreciated director of The Snowman. It took archival digging, new interviews and more, but it’s all come together.

With that, our slate:

Now, let’s go!

If animation has a gravitational pull, it’s that of the safe, formulaic, tried-and-tested house style. You’ve probably seen concept art that looked far better than the finished work and thought, “How could something so exciting end up so commonplace?”

But there’s a challenge perhaps even steeper than preserving the qualities of concept art in final animation. It’s when a director adapts a visual work from outside animation — a picture book, for instance — and tries to keep its style.

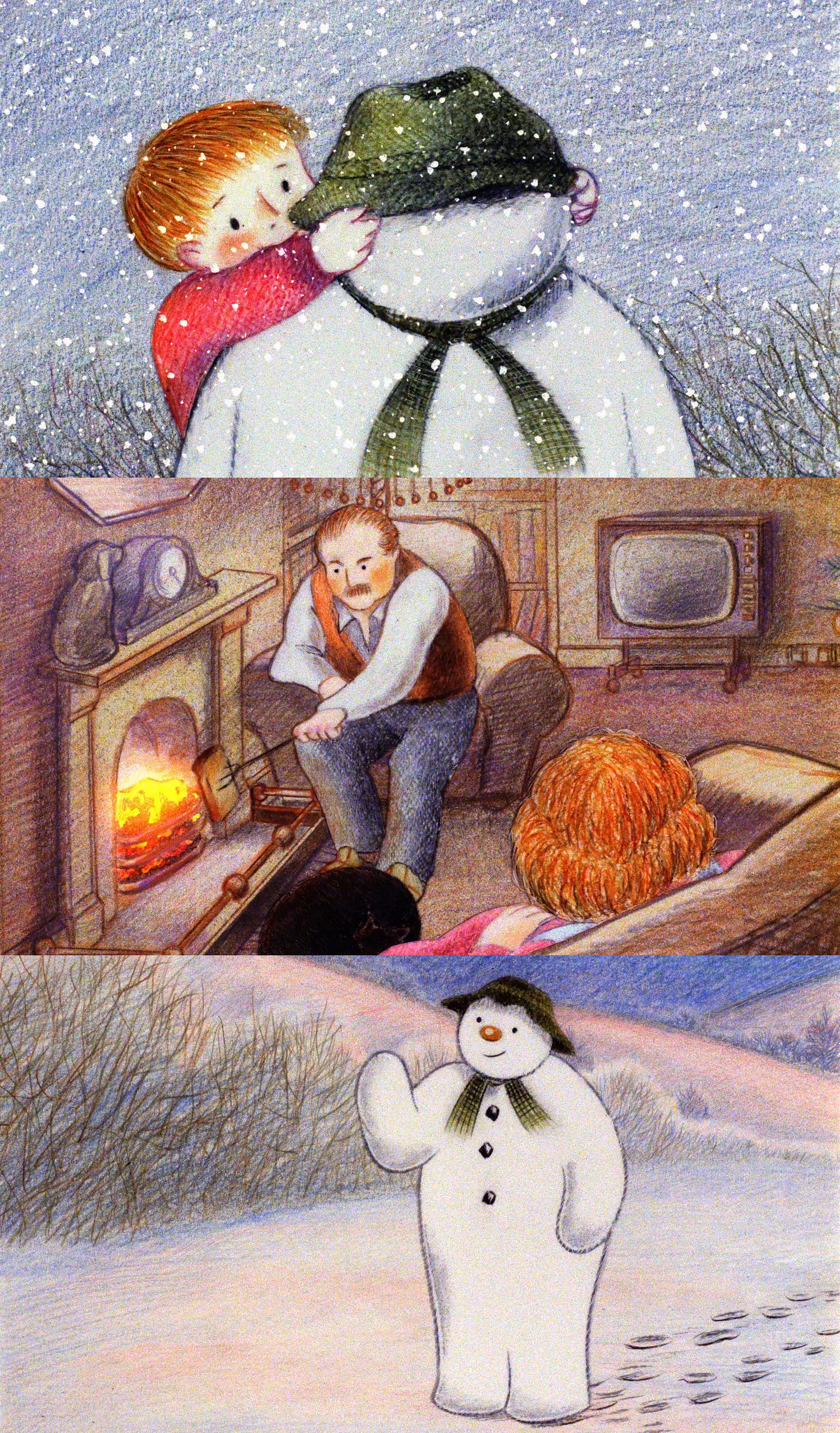

In Britain, a remarkable animator directed not one but two astonishing half-hours, each from a picture book by a different artist. She did full justice to the styles of both, and left her signature on them as well. The first of those films is world-famous: The Snowman (1982). The second, Granpa (1989), has fallen into obscurity, though you could argue it’s the greater of the two.

The animator behind them was Dianne Jackson, a name that should be more widely known; her work touched millions.1 Jackson’s special talent was converting illustrated books to animation. As her daughter Daniella Norton tells me by email:

Mum was incredibly dedicated to being faithful to the originals of the books that were turned into films. This was her superpower, if you like. She respected the originals, understood that [they were] the essence of all of the work she and her team of animators did… For her, it was everything to find a way of creating a film that had the same poetic effect and essence as the [source] book had. In my opinion, having grown up watching her, listening to her talk, all of her directing was in pursuit of that.

It was 1967 when Dianne Jackson entered British animation. Joining London’s TVC studio, she participated as an assistant animator in the mad venture that was Yellow Submarine (1968). Its director, George Dunning, was her mentor. “George never told you what to do, but rather let you express your own vision,” Jackson once said.2

Among the film’s other staff were John Coates, Dunning’s partner at TVC, and animation director Jack Stokes. The latter recalled the young Jackson as stylish, personable and excited to learn. “She just had a way with her … Nice kid, and very keen and interested in everything we were doing,” he said in 1993.3

By email, animator Hilary Audus shares her own impression of Jackson, whom she met at TVC in the ‘70s. They worked together on commercials. “What immediately struck me about her was her incredible drawing ability,” she remembers. “It was all so easy for her to work in any style brilliantly, and everyone looked up to her for this talent.”

Jackson’s career took a detour away from TVC in the mid-1970s. She moved to the studio Wyatt-Cattaneo, handling advertisements for chocolate, bananas and liquid antiseptic, and switching styles for each. Like many British animators of the time, she found commercials a valuable training ground. Jackson said she learned:

… how to put a point across very succinctly, because you have a very short time and you’ve got to be very positive. You learn all sorts of aspects of your craft doing that, which helps when you make bigger films.

That would be sooner than she could guess. After her interval at Wyatt-Cattaneo, she returned to TVC, then in transition. George Dunning had died in 1979, leaving the studio in the hands of John Coates. He was looking to animate a new British picture book, The Snowman, drawn in colored pencil by the artist Raymond Briggs.4

The Snowman book was a poor seller at first. Iain Harvey, executive producer of the animated version, suggested this came from its low page-count and lack of dialogue. For a bookshop browser, he said, “It was very easy to flick through the beautiful pages of artwork in a few moments and feel one had ‘full value’ from the experience.”

Animator Jimmy Murakami was the first pick to direct the Snowman film, but he said the idea “wasn’t [his] cup of tea.” So, he and Coates discussed giving Jackson the project instead. “I went for it immediately,” Murakami recalled, “because she had the ability, the sense of humor; she would give it that certain tenderness that she was always good at.”

A half-hour film was a massive jump from the half-minute commercials Jackson knew. However, her comments suggest she was unfazed:

I was offered the direction of Snowman completely out of the blue. It wasn’t [that] I’d been thinking, “It’s time I did a film.” I really hadn’t thought about it… I love the fact that you just follow what happens and you do a film if it comes up. I really have had no career pattern or anything. I just like to do one film at a time and I don’t want to know what’s round the corner at all.

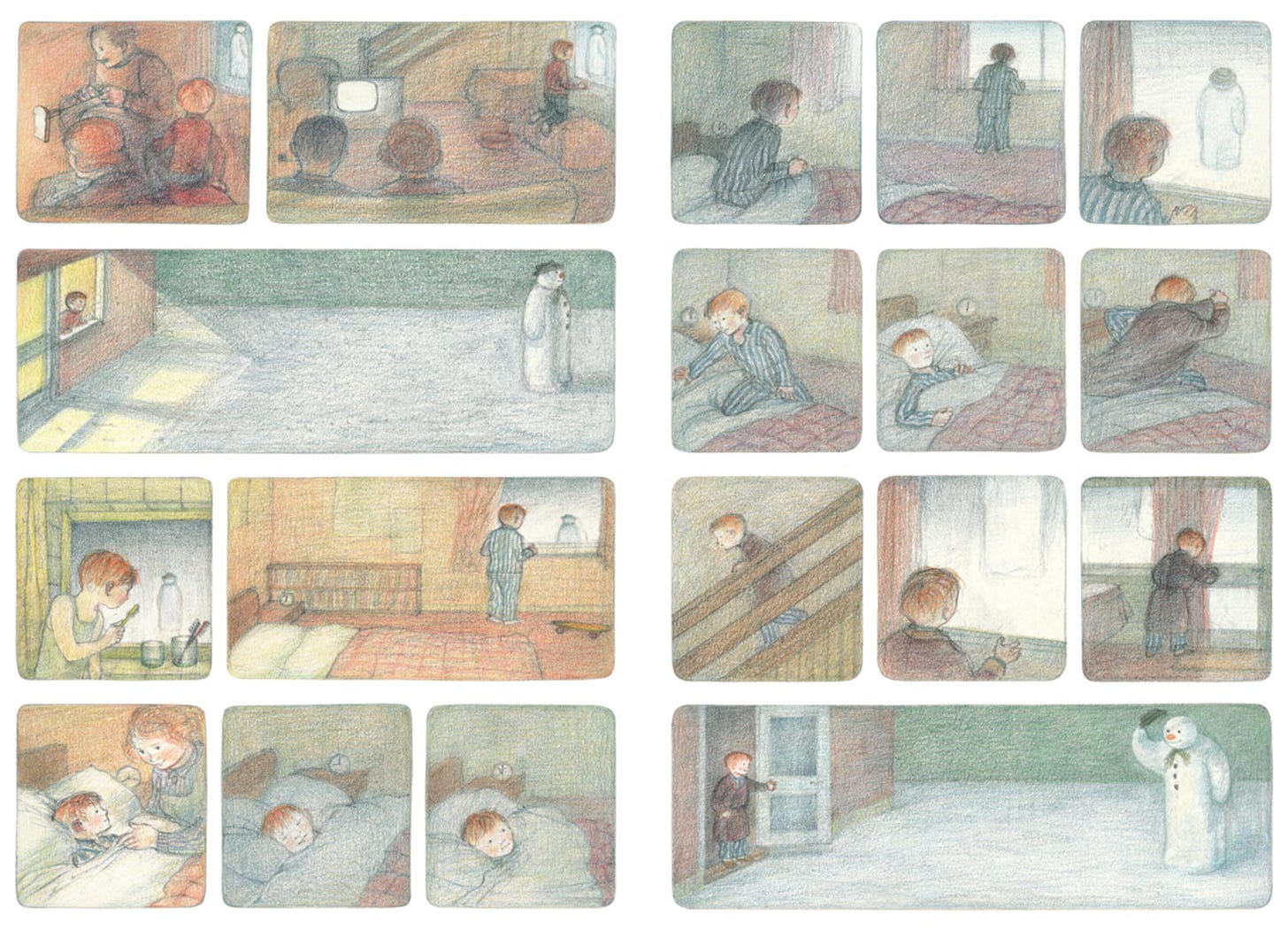

The story of the Snowman’s production has been told in this newsletter. The film’s visual style, emulating Briggs’ colored pencils, was achieved by painting the back of each cel and rendering the front with wax crayons. Jackson said she and another artist “stayed up until 2 a.m. one night, until we solved the technical problem of … that ‘crayon’ look so special to Raymond Briggs’ original.”5

Their system was maddeningly time-consuming. Why did Jackson go to so much effort? It tied back to the words of Daniella Norton, her daughter: she had to capture “the same poetic effect and essence” seen in the book.

If you look at Briggs’ Snowman after watching the film, you’ll be startled at what’s not there. In the original, the boy and his snowman fly as far as Brighton and look out to sea — a beautiful image — but they go no farther. There’s no journey to the North Pole, no snowmen dance and certainly no Father Christmas.6 Jackson’s version added them.

Briggs sometimes chafed at the film’s overshadowing of his book. However, in the 1993 documentary The World of Dianne Jackson and Friends, he said Jackson “took the quality that’s in the book and developed it and expanded it without in any way altering it.” He felt that the film even improved upon his material, made it “fuller and better.”

True, Briggs was less happy with a later animated sequence Jackson drew herself. It wasn’t in The Snowman but its far darker, not-for-kids successor, When the Wind Blows, released as a cinema feature in 1986. Based on another Briggs book, it’s a horrifying comedy about two befuddled British pensioners who try to prepare for a nuclear attack.

Jimmy Murakami directed that film at TVC, and Jackson animated an interlude with no equivalent in the original story. Her sequence comes when the wife, Hilda, has a romantic daydream, becoming a fairy on the wing. It’s exquisite to watch, with all the humor and tenderness Murakami attributed to Jackson. For Briggs, though, its whimsy went too far:

Dianne told me she was going to do this sequence of Hilda, standing in the garden, blowing a dandelion seed head, and then the camera would travel with the seed heads over the countryside, following the seeds on the wind, and I thought that was a terrific, poetical idea and could be marvelous. But, when I saw it, she seemed to have introduced these fairies with big, fat, pink bottoms floating about (laughs). I thought it was a bit awful, really, but I suppose it lightened the mood at that point in the film, which is what they wanted.

According to Jackson’s daughter, Briggs ultimately approved the film in its entirety, so he must have reconciled himself to it. Either way, animator Steve Weston (one half of Snowman’s flying sequence) was much more appreciative of Hilda’s daydream. He called it a chance “for Dianne to just literally float off and animate whatever came into her mind and it’s a terrific insight into what lovely thoughts she did have.”

Jackson would be involved in one other film connected to Briggs, namely Father Christmas (1991). David Unwin was its director, but she drew the storyboard. It mixes material from Briggs’ Father Christmas book and its sequel, Father Christmas Goes on Holiday,7 which present Saint Nick as a curmudgeonly working man. Jackson would’ve directed the film, too — but she was ill by then.

Just before that, however, she’d directed the remarkable Granpa, screened on television in 1989 (and rarely seen after that).

That one wasn’t a Briggs adaptation. Instead it was based on a 1984 picture book by John Burningham,8 about the loving relationship between a little girl and the title grandparent, going off on countless joyful adventures together… till they can’t be together anymore.9

The animated Granpa is stunning, with scene after incredible scene. The two get hurtled down a river by a singing whale, make their house an impromptu Noah’s Ark and brave a “Big Dipper” roller coaster by the sea.10 Like The Snowman, the film is driven by the glorious music of composer Howard Blake. But where The Snowman had one song, Granpa is an operetta, lifted especially by the voice of actor Peter Ustinov. “Not to mention a whale, a dog and some hippos!” Blake noted.

Burningham had “fear and trepidation” about his book’s adaptation, despite its sizable budget and staff.11 “Because it’s all very well … that a lavish film is going to be made of my work,” he said, “but how the hell are they going to do it? And what was very nice was at the earlier stages of the film, I could see that the way it was being made was in fact going to work.”

John Coates hailed Granpa as a much more complex and adult piece than The Snowman. For Sue Butterworth, one of its artists, it was a film in which Jackson herself was visible:

Whenever she drew children, they were instantly children, you just instantly recognized them for what they were. And in Granpa, Emily was possibly a bit of Dianne. And here was one particular scene where Emily is skipping, and instead of skipping like a nice little girl, both knees come up at each side and she skips like a little horse. And that just gave Emily the character that was needed; there were little touches like that that made you believe in that character.

Speaking about the depiction of youth in her films, Jackson brought up a memory of watching her own children play with her stepfather. “Through my life I hadn’t necessarily been very close to [him], but I noticed a whole world open up for him with his relationship with my children,” she said.

Daniella Norton highlights what was always there in her mother’s films: they were scrupulously faithful to the source books and drawn from the wealth of Jackson’s life experiences — “intangible elements that made the films whole and deep and beautiful.”

Granpa may be Jackson’s masterpiece. It’s been little-seen; shockingly, it was never released on DVD or Blu-ray.

Jackson, though, simply plowed further ahead. After supervising Father Christmas, she focused on TVC’s largest project yet: an animated take on the work of Beatrix Potter, an icon among British children’s illustrators.

“Without Dianne Jackson it is true to say that none of the Beatrix Potter adaptations would have been produced,” wrote Paul Madden of Channel 4. “To Frederick Warne, the publishers and guardians of the Potter heritage, she was the guarantee of the integrity of the series.”

The plan at first was to make a cinema feature, The Adventures of Peter Rabbit. The 1993 documentary about Jackson includes a gorgeous two minutes of test footage, placing a live-action girl amid Potter’s world and characters. This project was pitched to Warner Bros. and the first meeting was positive, but it ended up shelved.

Only as a cinema feature, however. Beatrix Potter’s stories would instead be animated as a series of half-hour TV specials under the umbrella name The World of Peter Rabbit and Friends. Initially, six specials went into production (three more followed). Jackson’s aim with them was to render the art and characters of Beatrix Potter just as they appear in her books.

This effort to put Potter’s work on screen was wildly ambitious, and reportedly Britain’s costliest animated project by that time, with a budget of $11 million (over $24.6 million now).12 Jackson was the coordinator of its several teams. In her words:

We’d been talking about Beatrix Potter for 10 years. We finally got it off the ground and really they need[ed] a focal director. I mean, when you have three directors working on three different stories, there does have to be somebody through whom people go, like Clapham Junction. … [B]ecause what you need to get at the end of the day is a series of films that are Beatrix Potter, not necessarily the shining talent of each individual director as such. What you need is those directors to put their talent behind trying to produce something which is really Beatrix Potter coming alive.

The Peter Rabbit staff worked in different places. Artists Sue Butterworth and Hilary Audus remember they had no face-to-face contact with Jackson at this time. “I occasionally rang her up on the telephone, often got David [Norton, her husband], and never thought anything more of it,” Butterworth said, “because the pre-production had been done and we all knew our jobs, so we just got on with them.”

For that reason, Jackson’s colleagues had no inkling for a long while of her health. Coates, who produced, only learned about it when the key Peter Rabbit people were getting medical checks and he told Jackson to schedule one. It was then she confided the truth: she had cancer.

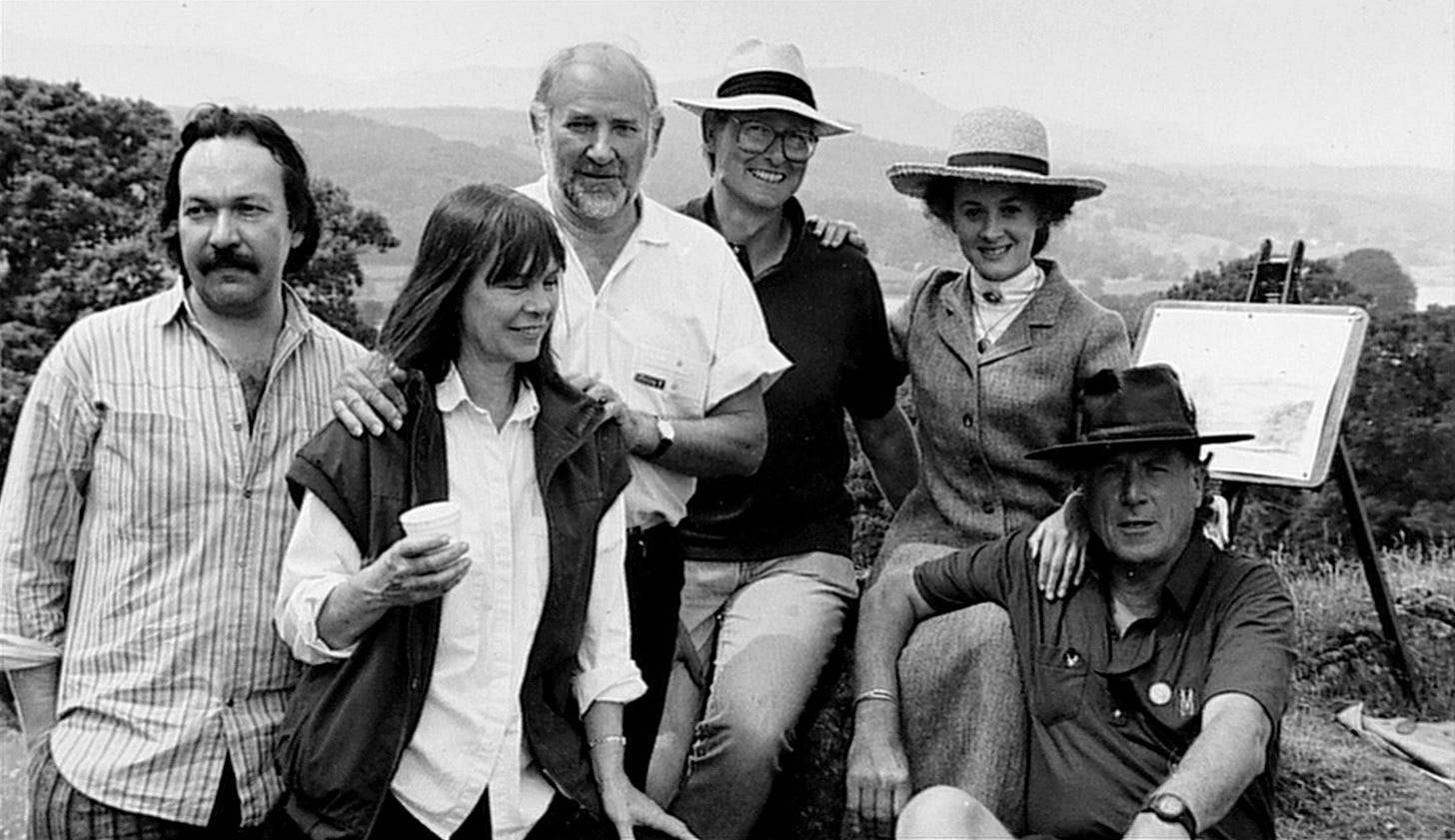

At first, Jackson responded well to treatment. Coates remembered her last summer in 1992, when she was present at the filming of new live-action material for Peter Rabbit at the Lake District, which would bookend the specials.

“She was just amazingly well,” Coates said. Her condition worsened in the months ahead, leading to her passing on New Year’s Eve 1992. A few days before, in the run-up to Christmas, the first Beatrix Potter special was broadcast. The series would win a multitude of awards around the world.

The people who knew Jackson have an abundance of warm memories of her. Colleagues recall her coming to TVC and insisting on chatting and drinking tea with the team, even when Coates was chasing her for a meeting. Producer Iain Harvey described an extraordinarily calm and unflappable director during the production of The Snowman. “She just let the pressure roll over her,” he said.

Her husband, David Norton, spoke of an artist who loved the seasons and the countryside in which she lived, beautifully recreated in her films. When she wasn’t drawing, Jackson could be often found in that countryside, on horseback. “If it was a good day and she could fit it into her work, she would go out and get a couple of hours on the horse and then get on with her work,” Norton said.

And, today, their daughter Daniella Norton remembers a mother who’d sometimes take a short nap in the afternoon — then plow on with her work into the small hours. Yet she looked out for others despite her busy life. Daniella recalls Jackson giving money to a friend’s mother whose daughter needed riding boots, though Jackson never let on about it. “She wanted to help people,” Daniella says.

That chimes with the experience of Jack Stokes at TVC, who said that Jackson went to huge lengths to help him when his wife fell ill. Unknown to him, that was after Jackson’s own cancer diagnosis. “Didn’t mention how she felt; she was only worried about how I felt,” he said. “Very amazing character.”

We’ll leave the last word to Daniella Norton. She’s also a part of her mother’s wonderful films — for example, Jackson would have her pose to better capture a child’s face. What does she think is most important and distinctive about Jackson’s work, as a lesson to animators today?

“A belief in a story,” she says, “and putting everything into that.”

Our grateful thanks to Daniella Norton and Hilary Audus for generously supplying their comments for this article.

Andrew Osmond is a British-based author and journalist, specializing in fantasy media, animation and anime. His books include “100 Animated Feature Films,” “BFI Film Classics: Spirited Away” and “Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist.” He has written thousands of articles and reviews for websites and print magazines over more than twenty years. If you’d like him to write for you, please drop him a line at [email protected]