The secretive Tory donor with the golden visa - and the ear of the Beehive

A British billionaire with links to offshore tax havens and a history of controversial political donations has been granted New Zealand residence, and he’s been meeting with government ministers in Wellington.

This story is supported by The Spinoff Members. To join them in supporting independent journalism, please donate today. The Spinoff: not backed by billionaires, backed by you.

Peter de Putron had a packed schedule for his trip to Wellington late last year. At 10am on Monday, December 2, the British billionaire met with Todd McClay in the forestry minister’s office at the Beehive, then was back at parliament at 2pm to catch up with finance minister Nicola Willis. That evening, he had dinner with science, technology and innovation minister Judith Collins at Jardin Grill at the Sofitel Wellington (Shed 5, the first choice, was booked out). At 11am the next morning, he returned to parliament for a meeting with associate finance minister David Seymour.

Four ministers in 25 hours.

These meetings had been efficiently arranged in the preceding two months by lobbying firm Thompson Lewis. Its co-founder David Lewis, the former press secretary of Helen Clark, had emailed McClay’s senior private secretary on October 16 to see if the minister was keen to meet with a forestry investor who was “expanding his interests in NZ”. Lewis’s colleague Wayne Eagleson had teed up de Putron’s next meeting. When he emailed Willis’s senior private secretary on November 4, Eagleson said he had already mentioned de Putron’s forthcoming visit to Wellington to “MOF” (minister of finance) in person the week prior. “Given his extensive investments world side [sic] across a number of sectors,” wrote Eagleson, “Peter … brings a perspective on the state of the international economy that I believe would be of interest to the Minister.”

Eagleson – who was described by John Key as “New Zealand’s most influential unelected official” when he was chief of staff for the then prime minister – had also organised de Putron’s dinner with Collins, which he joined. That email invitation had shared a few more details about Thompson Lewis’s high-profile client: he was the holder of a New Zealand residence visa under the (old) Investor Plus category, and was here for a few weeks “to visit his current investments and to look at new opportunities in this country”.

De Putron’s meeting with Seymour the following morning had been set up by Lewis, who emailed Seymour’s deputy chief of staff on October 10. “Wondering if David would be keen to meet if schedules align (its less ministerial and more as ACT leader)?” he wrote. “It would be purely a meet and greet but Peter [redacted text] so could have some insights that might be of interest to David… He expects to significantly expand his New Zealand investments over the next few years, and is building a portfolio across multiple sectors and regions.”

“Significantly expand his New Zealand investments” is a line that is likely to have made Seymour’s eyes light up. Finding ways to boost foreign investment is one of his official delegations as associate finance minister, but the meeting was not declared in Seymour’s ministerial diary, its existence revealed only via an Official Information Act request made by The Spinoff. A spokesperson for Seymour said that while he met with de Putron in his capacity as Act leader, there was “some discussion of overseas investment”, which is why the email exchange was released (only ministerial correspondence is subject to the OIA).

Just two days after Lewis reached out, Seymour announced a shake-up of our overseas investment policy settings, which he said were “the worst in the developed world” – so restrictive that wealthy offshore investors were giving New Zealand the cold shoulder, he lamented. Change was coming, though: a shake-up of the Overseas Investment Act to fast-track the assessment process, with “yes” being the default message sent to international investors unless a clear risk to New Zealand was identified.

‘Wondering if David would be keen to meet if schedules align (its less ministerial and more as ACT leader)? It would be purely a meet and greet but Peter [redacted text] so could have some insights that might be of interest.’

Peter de Putron, a 61-year-old hedge fund manager based in the British Crown dependency of Jersey, unquestionably has money to spend. An investor of his ilk showing interest in injecting some of that dosh into little old New Zealand is something that would be embraced by many, including the prime minister, who has not been shy about his desire to “roll out the welcome mat” for foreign investors – which he considers a crucial step in the noble quest for economic growth.

There is no suggestion of any wrongdoing on the part of de Putron, the ministers with whom he met late last year or the lobbyists who facilitated those meetings. Ministers regularly meet with people with vested interests, and an entire lobbying ecosystem has been built around this. But materials released to The Spinoff under the Official Information Act – and the responses to questions put to the British billionaire and several ministers – provide a glimpse into a secretive world of wealth and power, and the ways people with the necessary means and business interests may seek to influence those who run the country.

De Putron is among an increasing number of British billionaires based in the Channel Islands tax haven of Jersey. He grew up in neighbouring Guernsey, where his father was a local politician, before following the standard British upper-class path of attending Eton and Oxford. The most high-profile company under the umbrella of De Putron Fund Management Group is G-Research, a London and Dallas-based quantitative finance research and technology firm that pays its “quants” (essentially hedge fund coders) eye-watering sums to create algorithmic trading strategies and software – and does not take kindly to its trade secrets being stolen. According to the briefing prepared for McClay, G-Research “partners with charities and institutions to make careers in research and technology more accessible”. The briefing didn’t mention the substantial donations the company has made over the years to the Conservative Party and pro-Brexit thinktanks.

Often described as secretive, de Putron keeps out of the public eye. While his wife Hayley de Putron pops up in society snaps with the likes of Carole Middleton (mother of Catherine, Princess of Wales), not a single photo of him can be found online, but he has links to everything from Formula 1 (US court documents suggest he is the ultimate owner of the Williams F1 team, with employees referring to him as ODL or “our dear leader”), to fuel to, in New Zealand at least, forestry.

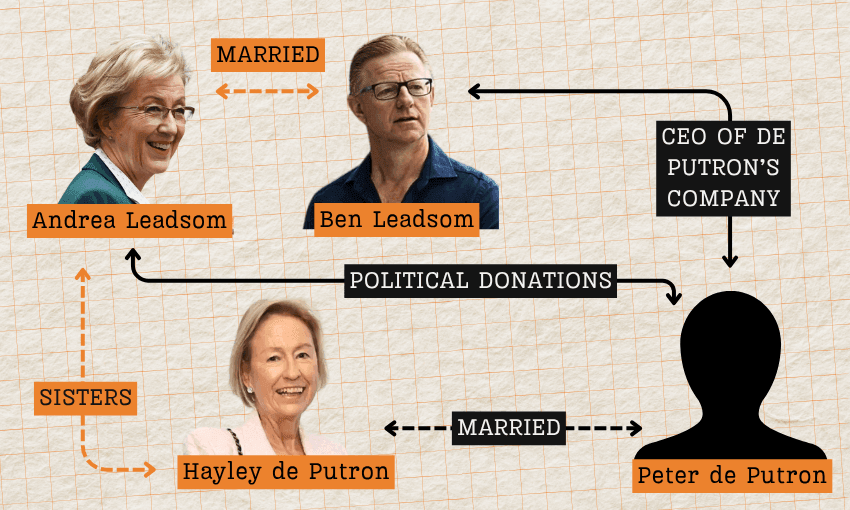

De Putron’s wife Hayley (nee Salmon) is the sister of Andrea Leadsom, a former Conservative MP who held several ministerial positions over her decade in the UK parliament (she stepped down at last year’s election). Described by media as an “arch-Brexiteer”, she twice stood for the party’s leadership, missing out to Theresa May in 2016 and then Boris Johnson in 2019. Leadsom’s husband Ben Leadsom is the CEO of G-Research, and Andrea Leadsom herself worked for a number of de Putron’s companies before she went into politics (though question marks were raised about whether her finance career was as high-flying as her CV suggested).

These family connections led to some controversy for the politician. When she first became a minister in 2014, it emerged that de Putron had been giving hefty sums to the Conservative Party, despite donations from the Channel Islands being banned – he got around this rule by using his UK-registered companies. This information came out after de Putron was named in the Jersey files, documents leaked from a firm called Kleinwort Benson that helped its wealthy clients exploit tax loopholes. A leaked seating plan from the Tories’ 2014 black and white party, a high-profile annual fundraising event, showed de Putron was seated at the same table as then health minister Jeremy Hunt. A Labour MP suggested the donations to the Tories was a “cash for office” arrangement for Leadsom, but the minister denied she was involved in any way. De Putron continued to donate to the Tories until at least 2017. Links to the Jersey government have also been alleged, with de Putron reportedly having influenced politicians there to pull funding for a new hospital in 2017.

Twenty years prior, de Putron had founded De Putron Fund Management, with seed funding from Hungarian-American billionaire George Soros (who, interestingly, is known for supporting liberal causes, including the anti-Brexit movement). Trying to get a handle on all de Putron’s current business interests is not easy: he’s “an intensely private individual whose affairs are routed through a complex network of companies”, as Australian business news site Capital Brief put it, adding that those companies had a “habit of changing names”. De Putron caught the eye of Australian business media in 2023 after his hedge fund Bell Rock Capital Management waged an activist shareholder campaign against Whitehaven Coal, and was censured by the Takeovers Office.

According to the MPI briefing prepared for McClay, de Putron is the sole shareholder of a company called New Zealand Forest Industries (NZFI) Ltd, through which he owns 830 hectares of commercial pine forest and 230 hectares of native bush in the Marlborough Sounds. Overseas Investment Office documents released to The Spinoff, however, suggest his land holdings total closer to 1,780 hectares. According to the documents, de Putron acquired NZFI Ltd when his British Virgin Islands-registered holding company, Issoria Offshore Ltd, was granted permission to acquire NZFI Ltd’s Singapore-registered parent company, NZFI Sing, in July 2019. NZFI Ltd owned a 1,116-hectare forest at Te Whanganui/Port Underwood in the Marlborough Sounds known as Underwood Forest. Consent was also granted for the purchase of Hakahaka Forest, a smaller “bolt-on” block immediately next to Underwood. Later that year, two further consents were granted for NZFI Ltd to acquire another unnamed block adjoining Hakahaka, as well as Whataroa Forest across the bay.

The applications were assessed under the “special forestry test”, which required overseas individuals purchasing existing forestry to use the land exclusively or nearly exclusively for forestry activities, to replant after harvesting, and to not live on the land, as well as to put in place certain arrangements including public access, protection of habitat for indigenous plants and animals, and protection of historic places. The special forestry test was introduced by the then Labour-led government in October 2018 as a way to fast-track big forestry sales to overseas investors, at the same time as foreign purchases of residential land were prohibited in what is known as the foreign buyer ban. The policy led to overseas forestry companies becoming the biggest landowners in Aotearoa and prompted backlash from farming groups and environmentalists alike.

To be approved under the special forestry test, buyers also had to meet certain criteria under the “investor test”, including having business experience and acumen relevant to the overseas investment, and the “good character test”, whereby offences or contraventions of the law had to be taken into account, along with “any other matter that reflects adversely on the person’s fitness to have the particular overseas investment”. In relation to the second condition, the Overseas Investment Office decision released under the OIA noted “one relevant matter” that was uncovered by “open source background checks”: “The information provided shows that Mr de Putron is has connections to senior ranking politician in the UK [sic],” it read. “A UK based company in which he has an interest made a donation to the political party to which his sister in law belongs. His sister in law is the UK leader of the House of Commons and in the UK Government Cabinet.

“We do not have any information to suggest the donation was made unlawfully. Mr de Putron has made a positive statement that the donations were fully disclosed in compliance with applicable law. Related matters published in the Guardian do not appear to be substantiated… We do not consider this is a matter that affects Mr de Putron’s fitness to have this investment.”

The decision noted that de Putron’s “overarching investment intention is to build a forestry-based investment portfolio of at least two rotations (at least 50 years). This plan includes acquiring multiple forests for diversified revenue streams, investment in research and development for hybrid pine tree species, and investing in downstream manufacturing to develop high value timber products, principally for structural use.”

‘We do not have any information to suggest the donation was made unlawfully. We do not consider this is a matter that affects Mr de Putron’s fitness to have this investment.’

De Putron was granted residence here under the Investor Plus programme, introduced as part of the John Key-led National government’s business migrant policy in 2009. Also known as the Investor 1 category or, colloquially, the “golden visa”, Investor Plus granted residence to people who invested $10 million or more over three years and were in the country for 73 days a year, or, from 2011, just 44 days a year. This is the category through which both Peter Thiel and Kim Dotcom secured residence in 2006 and 2010 respectively. In 2011, Thiel was controversially granted New Zealand citizenship, despite having spent just 12 days in the country in the past five years.

In 2022, Investor Plus was replaced by the Labour government with the Active Investor Plus visa, which had stricter criteria. Earlier this year the current government overhauled the Active Investor Plus to make its criteria looser, more in line with the old Investor Plus visa. MBIE confirmed de Putron was granted residence under the Investor 1/Investor Plus category but declined to provide any further details, citing privacy. Given there is no mention of de Putron having residence in the Overseas Investment Office documents from 2019, and the category changed in September 2022, we can presume this occurred at some point in between, during the term of the last Labour government.

It’s not clear how or when de Putron became interested in New Zealand, but one connection is Raymond (Ray) Hine, a New Zealand engineer who was involved in setting up forestry behemoth Carter Holt Harvey in the 1980s and is now based in Jersey. The Companies Register lists Hine as one of two directors of NZFI. This is where it gets confusing, so hold tight. Hine became a director of the company under its previous name, New Zealand Forest Product Holdings Ltd (NZFP Holdings Ltd), in April 2017. The company had been set up the year prior by Brian Henry, whose family had long been involved in the forestry industry and who is best known as Winston Peters’ long-time lawyer and “blood brother”. Henry sold the company to Attalus, a Cayman Islands-registered company, soon after it was registered in 2016, and Attalus in turn sold it to NZFP Holdings (Singapore) Pte Ltd a couple of months later. In December 2016, the Overseas Investment Office granted approval for New Zealand Forest Product Holdings Ltd and an overseas individual named Patrick Egan, a hedge fund manager resident in Saint Kitts and Nevis, to purchase Underwood Forest.

In April 2017, Hine, with a Jersey residential address listed, joined Henry as a director of the company, as did another Jersey-based individual called Robert Minty. In June 2017, New Zealand Forest Product Holdings Ltd’s name was officially changed to New Zealand Forest Industries (NZFI) Ltd. The following year, Minty ceased being a director, and Auckland-based investor Randolph van der Burgh came on board – he remains co-director with Hine to this day. Henry ceased being a director on the last day of 2018. Hine’s residential address in the Companies Register has since been changed to multiple different Auckland and New Plymouth addresses.

In September 2019, the British Virgin Islands-registered Issoria Offshore Ltd was listed as NZFI’s ultimate holding company, and in the months that followed its shares were passed back and forth between NZFP Holdings (Singapore) Pte, NZFI Holdings (Singapore) Pte Ltd, and Issoria. In March 2021, Issoria became the sole shareholder until October 2023, when a single extra share was added and allocated to an individual, rather than a company, for the first time: one Peter de Putron of Jersey.

Under the terms of the Overseas Investment Office approvals for de Putron’s purchases of the Marlborough land, he is not allowed to live there – an existing homestead on the largest block was set to be demolished in 2022 and replaced with forestry worker accommodation, and a cottage on another block must solely be used to house workers. The residence visa he has been granted since the purchases doesn’t get around the foreign buyer ban, either – to purchase residential property, the buyer must be considered to be “ordinarily resident” in New Zealand, meaning they must have lived here for at least 12 months and have been physically present in the country for at least half of that. But the foreign buyer ban, at least in its current guise, could be on the way out.

De Putron’s land is a stunning spot, however, offering “an abundance of highly desirable Sounds coastline” as the Harcourts listing advertising the property in 2016 put it. The ad described it as a “forestry/residential subdivision”, noting there was “the option to capitalise on the approved Resource Consent permitting a unique subdivision containing 25 well located residential sections that will enjoy easy access to the beach and coastal views of this world renowned location”. That resource consent lapsed in 2021, Marlborough District Council documents show.

De Putron was in New Zealand last year at the same time as his compatriot and fellow Conservative Brexiteer, former UK prime minister Boris Johnson. As de Putron was meeting with David Seymour at parliament on Tuesday, December 3, Johnson was regaling an audience including John Key, Winston Peters, Gerry Brownlee and Wayne Brown at an Auckland “long lunch”. He loved New Zealand, Johnson said, but had read that it had become “the number one destination for paranoid billionaires. This country is where the bankers are building their bonkers bunkers.”

There has been much conjecture about these “bonkers bunkers” over the years but few firm details, though a number of companies are said to have shipped or built bunkers here. (Thiel’s plans for an elaborate bunker-style lodge in Wānaka were thwarted when he was denied resource consent in 2022.) The Covid-19 pandemic underscored the appeal of New Zealand as a safe haven: in 2020, Silicon Valley billionaire Mihai Dinulescu bunkered down on Waiheke and in early 2021, Google co-founder Larry Page was granted residence under the Investor Plus scheme.

Recently the government has pushed the idea of New Zealand as a refuge in an increasingly uncertain world, with Christopher Luxon telling attendees at March’s investment summit the country was “a very attractive destination for anyone looking to take shelter from the global storm”. Immigration minister Erica Stanford recently said that since the investor visa settings changed on April 1, 80 applications had been approved in principle, including from tech co-founders of “very big, well-known companies that you would probably use everyday”.

While there is no evidence de Putron has set his sights on a Marlborough Sounds bolthole, it is not hard to imagine how such a slice of paradise might appeal to any individual seeking splendour and privacy. Te Whanganui/Port Underwood is a large, sheltered inlet in the east of the Marlborough Sounds, divided by a peninsula known as “the Tongue”. De Putron’s land covers much of the west coast of the inlet, stretching from Uruti Bay in the southwest, north through Oyster Bay and Hakahaka Bay (the small settlements of Oyster Bay and Port Underwood are carved out from his holdings), Whangataura Bay and Opihi Bay, then stretching around to cover the Tongue itself, and extending north to Hitaua Bay. Another block of land is across the water to the east of the Tongue, at Tumbledown Bay and Jernams Bay.

It’s an area steeped in history, both Māori and Pākehā. Home to substantial pre-European Māori settlements, Te Whanganui has significance to a number of Te Tau Ihu iwi, including Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tā, Rangitāne, Ngāti Rārua and Ngāti Toa Rangatira. It was the site of one of the earliest European settlements in New Zealand, according to an archaeological assessment commissioned by forestry managers Merrill Ring for the Overseas Investment Office in 2018, and became a prominent whaling hub from the late 1820s.

Underwood Forest, the largest site among de Putron’s holdings (shaded yellow in the map above right), is home to 17 recorded archaeological sites, nine being close to harvestable pine trees that potentially could be affected by forestry operations. These include the site of a kāinga, a number of middens, pits and terraces (indicating Māori habitation and agriculture), a historic house site, and the Daken family cemetery at Opihi Bay, where eight descendants of William Deakin (the spelling at some point changed to Daken), an American whaler who jumped ship and cleared the land for farming, are buried. Another family cemetery is at Whangakoko Bay on the eastern side of the Tongue.

Forestry in the Sounds has a long history, and has long been contentious. In the first half of the 20th century, much of the native bush that covered the area was cleared for farming, but by the 1960s and 70s farming such remote country was no longer economically viable, forcing a rethink of possible land usage, according to the archaeological assessment from 2018. The first trees were planted at Underwood Farm, now Underwood Forest, in 1968, and by 1984, 522 hectares were in forestry.

Even back then, people warned that the steep hills of the Sounds may not be suitable for forestry: soil erosion causes sediment to end up in the ocean, clogging seabeds and damaging ecosystems. De Putron’s land is considered ecologically significant, home to a number of wetlands and SNAs (significant natural areas) that were referenced in a 2018 resource consent application to harvest small areas of forest. The application, which was approved, said trees that couldn’t be felled without damaging an SNA or wetland would be poisoned to rot down, and a buffer area of eight metres around the perimeter of the wetlands would be planted in native riparian species. The buffers of mainly wetland vegetation between the areas of harvest and the coast would filter sediment from run-off, said the application.

Future harvests – the MPI briefing to the forestry minister indicated “significant portions” of NZFI’s forest would be due for harvest in the next decade – may not require such thorough planning. The Resource Management Act is currently being reviewed, with a replacement to focus on property rights. Councils no longer need to map SNAs and how existing ones are dealt with is also under review.

With a history of political donations and alleged attempts to influence policy in the UK and Jersey, it’s worth asking what de Putron’s objective in meeting with New Zealand politicians was. The Spinoff put a number of questions to the investor through Thompson Lewis, which David Lewis said he passed on to de Putron’s “NZ advisers” but did not receive a response.

In response to questions from The Spinoff, Nicola Willis said via a spokesperson that she met with de Putron “to discuss his perspective on the international economy as an investor”. She has not been in contact with him since, “but if the opportunity arose to engage again, the minister might choose to do so”. Todd McLay, meanwhile, said, “I met with Mr de Putron in my capacity as forestry minister to discuss his tree investments. It was also a good opportunity to hear an investor’s perspective on New Zealand and explore ways to grow the economy through foreign direct investment.” As for Collins, all she revealed was, “Peter de Putron is one of a number of people I met with while science, innovation and technology minister as part of the government’s push to grow the economy.”

Seymour (who, remember, met with de Putron in his capacity as Act leader, though there was “some discussion of overseas investment”) said, “Peter reached out to meet with me last year. I was happy to do so as he has an impressive business background, and I was interested to hear his thoughts on what it’s like to do business in New Zealand. If we want to be a wealthy country, we need to have policy settings that encourage people to invest and create more jobs and opportunities here.”

‘Peter reached out to meet with me last year. I was happy to do so as he has an impressive business background, and I was interested to hear his thoughts on what it’s like to do business in New Zealand.’

The overseas investment overhaul was already under way when de Putron’s December meetings took place, but it has certainly ramped up in the months since. In January, the new Invest NZ agency was announced ($85 million was set aside in the budget to set it up), followed by the golden visa revamp in February. Soon after, Seymour revealed further details of the reform of the Overseas Investment Act – including scrapping the special forestry test (under which de Putron’s application was assessed) and speeding up the already fast-tracked consent process to 15 days. Legislation to amend the act is expected to be introduced this month. March saw an infrastructure investment summit held in Auckland, when a number of announcements were made including changes to foreign investment fund rules to lessen the tax burden on overseas investors. In May’s budget, $65 million was set aside to change New Zealand’s thin capitalisation rules which the government believes are discouraging foreign investment.

Considering he was meeting with de Putron as Act leader, and the party has a habit of attracting high-net-worth donors, The Spinoff asked Seymour if the topic of donations came up during their meeting. (People who live outside of New Zealand and are not citizens are not permitted to make donations in excess of $50 to political parties here, but as in the UK, a loophole exists through which donations can be made via New Zealand-registered companies.) According to the latest declaration of party donations for the 2024 calendar year, NZFI Ltd has not donated to any party, and Seymour said donations were not discussed.

With what’s looking likely to be a tightly fought election just over a year away, the quiet quest for influence over our elected officials is likely to ramp up, and de Putron will be far from the only cashed-up client working with lobbyists to secure a spot in the diaries of our leaders. Even if the mysterious billionaire does return to New Zealand to make his presence (and feelings) known to our politicians, we may never put a face to the name. While the caricature of globetrotting billionaires may often be one of headline-grabbing interjections and flamboyance, many of the most powerful – and effective – of their number prefer to operate as invisibly as possible.