BMC Psychology volume 13, Article number: 722 (2025) Cite this article

Effort-reward imbalance is a mismatch between the amount of effort teachers put into their job and the amount of reward they get, which is quite common among rural preschool teachers in China. The feeling of effort-reward imbalance may result in teachers’ lack of passion, emotional exhaustion and other emotional problems at work, and then affect their feeling of well-being in work condition. Psychological capital as a kind of positive psychological resources may buffer the negative effect of effort-reward imbalance on rural preschool teachers’ occupational well-being. In this study, 3065 rural preschool teachers in China were selected to explore the effect of the effort-reward imbalance on their occupational well-being, as well as the role of emotional exhaustion and psychological capital. The results show that: (1) effort-reward imbalance could negatively predict occupational well-being; (2) emotional exhaustion played a mediating role between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being; (3) psychological capital moderated the direct path from effort-reward imbalance to occupational well-being, and also moderated the indirect path from effort-reward imbalance to occupational well-being through emotional exhaustion. That is, a high level of psychological capital can alleviate the direct negative predictive effect of effort-reward imbalance on rural preschool teachers’ occupational well-being, and also alleviate the indirect negative effect through emotional exhaustion on occupational well-being. The results have important theoretical and practical significance for improving the occupational well-being of rural preschool teachers and reducing their sense of effort-reward imbalance.

Occupational well-being is construed as a positive evaluation of various aspects of one’s job, including affective, motivational, behavioural, cognitive and psychosomatic dimensions [22], which is defined as a positive emotional state resulting from harmony between the sum of specific environmental factors and personal needs, expectations of teachers [1]. Teachers’ occupational well-being affects their teaching practice and interaction with students, which in turn affects students’ academic, social and emotional development [26]. High level of occupational well-being can increase teachers’ work engagement, reduce their psychological stress, and help them to be more positive to their professional development [30, 31]. On the contrary, low levels of occupational well-being can lead to job burnout, occupational stress and even turnover intention [40]. At present, the occupational well-being among preschool teachers in rural areas is not optimistic. A study focused on 1136 Chinese rural preschool teachers in Guangdong province found that only 9.1% can perceived occupational well-being, 43.9% among them only sometimes or never perceived occupational well-being( [8]). A recent study found that occupational well-being of rural preschool teachers was very low [25], which was also significantly lower than that of urban preschool teachers [55]. For a long time, the quality of teachers in rural kindergartens has been low, and the poor stability and serious shortage of teachers have consistently posed challenges for early childhood education in rural China [21]. Therefore, it is of positive significance for the development of rural preschool teachers to explore the influencing factors of occupational well-being. According to previous studies, occupational well-being is primarily influenced by personal factors (such as gender, professional experience and education), professional factors (such as attitudes, beliefs and professional development activities), and organizational factors (such as school atmosphere, resources, management quality, workload and employee relations) [46]. And the effort-reward imbalance is not only a problem at the organizational level, but also affects the individual's interaction with the organization [51]. The effort-reward imbalance at work can lead to negative physical outcomes such as poor well-being [12].Therefore, this study will focus on the impact of effort-reward imbalance on the occupational well-being of rural preschool teachers and the underlying mechanism involved in this relationship.

The Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) model, defined originally by Johannes Siegrist [48], aims to explain how the balance of costs and gains in social exchanges. According to the effort-reward imbalance model, high demands at work and heavy obligations in individuals’ lives may lead to high effort, while inadequate treatment, low self-esteem, and fewer promotion opportunities will result in low rewards [27]. The imbalance between high effort and low rewards can cause emotional distress and further lead to persistent tension [54], which can have a negative impact on employees’ health and well-being [50]. For a long time, preschool teachers’ professionalism has been questioned, which could not get enough respect and recognition by the society, however they also have to invest a lot of time and energy, they may feel very frustrated( [68]). This situation is the important sources of feeling of effort-reward imbalance [72].In fact, compared with teachers in other educational stages, preschool teachers have to shoulder more responsibilities for childcare and education. They often face a larger workload and longer working hours, but their treatment and career development were not paid enough attention by the society [19, 28, 29].Furthermore, compared with urban areas, preschool teachers in rural areas are more difficult, they often need to invest more time and energy to take care of the preschool children whose parents are not at home, they also spent large amount of time on their own family, which will make them feel exhausted [53]. And then the lower wages and social status, and lack sufficient professional development opportunities and platforms during their work would aggravate their effort-reward imbalance [61]. So preschool teachers in rural areas often feel high level of effort-reward imbalance( [68]).Empirical studies conducted on nurses, police, employees in companies and college teachers have shown that effort-reward imbalance could negatively affect their occupational well-being [10, 20, 47, 66, 70]. However, in the existing studies, less focused on the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being among rural preschool teachers. Thus, we propose hypothesis1: effort-reward imbalance can significantly negatively predict the occupational well-being of rural preschool teachers.

According to Social Exchange Theory, individuals can seek fairness and reciprocity in social interaction, when this exchange is unbalanced, individuals may feel dissatisfied and frustrated [6]. When there is an effort-reward imbalance, the violation of reciprocity triggers negative emotions and activates the brain's frustration-reward mechanism [49]. When there is a lack of reciprocity between work costs and benefits, employees often suffer from emotional distress and show a higher degree of emotional exhaustion, which further affects their work performance [16]. In addition, according to the Conservation of Resources theory, individuals always strive to obtain and preserve valuable resources,when they successfully obtain and preserve valuable work resources, they are prone to obtain occupational well-being, conversely, the absence of such resources can lead to job burnout [23].Preschool teachers tend to surface expression when they experience effort-reward imbalance, which requires extra effort to maintain external emotions, and internal and external inconsistencies can reduce self-authenticity and ultimately lead to emotional exhaustion [43, 69]. Emotional exhaustion is a state of exhaustion of individual psychological and emotional resources [37], which defines the stress element of burnout and it is often seen as a sign of educators'working well-being [15]. For preschool teachers, especially in rural areas usually experience high level of effort-reward imbalance, high work demands, low level of work reward and social identify, less chance of professional development would constantly consume their emotional resources, and then result in emotional exhaustion [18, 71]. Emotional exhaustion at work can lead to preschool teachers'skepticism about the value and ability of their work, which has a direct impact on their work engagement, which in turn leads to burnout and turnover, and ultimately affects their occupational well-being(Diana et al.,2020). In addition, the complex interactions with young children, families, and colleagues objectively require preschool teachers to engage in intense emotional labor, and the long-term depletion of emotional resources negatively affects their professional well-being [69]. Empirical study hasshown that the degree of emotional exhaustion of preschool teachers is closely related to their professional well-being [60]. Based on the above theories and empirical studies, we propose hypothesis 2: emotional exhaustion plays an mediating role between effort-reward imbalance and their occupational well-being.

Although preceding part of the text have mentioned the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being among preschool teachers, not all teachers experiencing effort-reward imbalance would result to emotional exhaustion or exhibit lower levels of occupational well-being. Researches indicated that certain positive psychological resources (e.g., psychological capital) can buffer the negative affect caused by stress and promote individual well-being [33, 36]. Psychological capital is a general term for various positive mental states including self-efficacy, hope, optimism, resilience, emotional intelligence and so on, which plays a catalytic role in the process of personal growth and professional development [9, 34]. According to Psychological Capital Theory, psychological capital enables employees to cope with various stressors, channel energy into their work [42], and enhances their job engagement and occupational well-being [2]. When individuals possess high levels of psychological capital, they can maintain an optimistic attitude toward unsupported external work environments, thereby reducing the risk of job burnout and other mental health issues [13]. Empirical studies also confirm that psychological capital positively influences individual well-being and emotional regulation [5, 63]. So, psychological capital can be an important protective factor to buffer the adverse affect of negative environment(e.g., effort-reward imbalance) and other stressors. Preschool teachers with high level of psychological capital often utilize it as a critical supplementary resource in contexts with limited external resources [17], which help them to adopt proactive strategies to navigate high-pressure work environments [35], and reduce risks of burnout and mental health problems [18]. High level of psychological capital enables teachers to sustain high expectations for their work, maintains confidence in their professional competence, preserves long-term enthusiasm and motivation [52],and mitigates negative emotional outcomes caused by negative environment factors including emotional exhaustion [7]. Based on this, we propose hypothesis 3: psychological capital can moderate the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being, and can also moderate the indirect path from effort-reward imbalance to occupational well-being through emotional exhaustion.

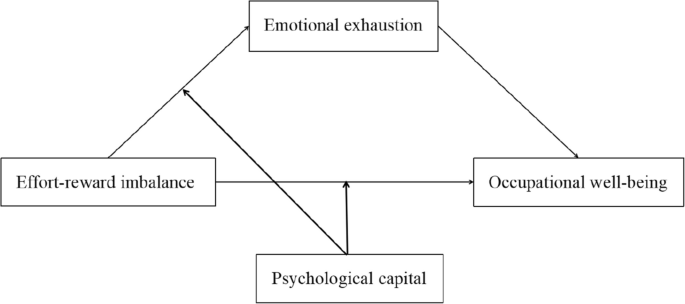

In summary, according to relevant theoretical and empirical studies, Chinese rural preschool teachers usually experienced high level of effort-reward imbalance, which may have negative affect on their occupational well-being. In addition, teachers’ occupational well-being is related to the stable development of rural preschool education. So, it is of great significance to explore the influencing mechanism of effort-reward imbalance on occupational well-being, and find the protective factor of teachers’ occupational well-being. In existing studies, less examined the mechanism from effort-reward imbalance to occupational well-being, especially among the group of rural preschool teachers. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being, and include teachers’ emotional factor(emotional exhaustion) as mediating variable and individual protective factor (psychological capital)as moderating variable. The hypothetical model was shown in Fig. 1.

The survey was started in October to November 2023, stratified sampling method was adopted from the 11 regions of Zhejiang Province, mainland China, 10 towns were selected from each region, and 2 rural kindergartens were selected from each town, for a total of 220 kindergartens and 3300 rural kindergarten teachers were recruited. Among the 3300 questionnaires, 235 questionnaires were excluded because of too much missing data, and a total of 3065 valid questionnaires were retained. Among the participants, mean age was 32.08 ± 7.10 years; there were 35 male teachers and 3030 female teachers; 40 teachers were high school graduates; 1013 teachers were college graduates and 2012 teachers were bachelor graduates; there were 1010 teachers with teaching age less than 5 years; 834 teachers with teaching age 6–10 years; 680 teachers with teaching age 11–15 years; 541 teachers with teaching age more than 16 years; 1854 teachers with the income less than 50000RMB a year, 645 teachers with the income 50,000-80000RMB a year, 372 teachers with the income 80,000−100000RMB a year, 194 teachers with the income more than 100000RMB a year. All the demographic information were included as control variables during the following analysis.

Effort-reward imbalance

Teachers’ effort-reward imbalance was measured using the Chinese version of Effort-Reward Imbalance Scale (E-RIS, [48, 56]), which consists of 23 items and divided into three dimensions. This study used two dimensions: (1) External effort (6 items, e.g., my job requires me to take on a lot of responsibilities),(2) Reward (11 items, e.g., combined with all my efforts and achievements, I gained enough respect and prestige in my work). Participants rated each items on a five-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree). The ratio of the score of Effort*11 and Reward*6 represents the level of effort-reward imbalance. The larger of the value indicated the stronger feeling of effort-reward imbalance. Confirmatory Factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the structural validity of the scale, the result demonstrated good model fit indices of the three-factor model(χ2/df = 2.58, RMSEA = 0.06, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.98).The Cronbach’α of the two dimensions of External Effort and Reward Scale were 0.90 and 0.87.

Emotional exhaustion

Teachers’ emotional exhaustion was measured using Chinese version of Teacher Burnout Scale(TBS, [37, 57]), which consists of 22 items assessing teachers’ burnout on three subscales. In this study, we used the Emotional Exhaustion subscale(9 items, e.g., I feel a loss of passion for teaching) to assess teachers’ emotional exhaustion. Participants rated each items on a seven-point Likert scale(0 = never, 6 = always). Confirmatory Factor Analysis was conducted to evaluate the structural validity of the scale, the result demonstrated good model fit indices of the three-factor model(χ2/df = 3.12, RMSEA = 0.07, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.97). In this study, the Cronbach’α of the Emotional Exhaustion subscale was 0.94.

Occupational well-being

Teachers’ occupational well-being was measured using the Chinese version of Teachers’ Occupational Well-being Scale(TOWS, [55]), which consists of 15 items(e.g., My kindergarten makes me feel happy). Teachers rated each items on a three-point Likert scale(1 = totally disagree, 3 = totally agree). Confirmatory Factor Analysis was conducted to evaluate the structural validity of the scale, the result demonstrated good model fit indices of the one-factor model(χ2/df = 2.56, RMSEA = 0.06, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.98). In this study, the Cronbach’α of the overall scale was 0.96.

Psychological capital

Teachers’ psychological capital was measured using the Chinese version of Psychological Capital Scale (PCS, [34, 62]), which consists of 24 items(e.g., If I find myself stuck at work, I can think of many ways to get out of it) on four subscales. Teachers rated each items on a six-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 6 = totally agree). Confirmatory Factor Analysis was conducted to evaluate the structural validity of the scale, the result demonstrated good model fit indices of the four-factor model(χ2/df = 2.38, RMSEA = 0.06, TLI = 0.96, CFI = 0.98).In this study, the Cronbach’α of the overall Psychological Capital Scale was 0.95.

All the teachers are from rural kindergartens in Zhejiang province, China. We contacted the heads of kindergartens in each region, and sent the link of the questionnaire survey to each kindergarten teacher. Before the data collection, our study passed strict ethical review, and every teacher who participated in the survey signed an informed consent. We informed every teacher of our research content and purpose, as well as the precautions when filling in the questionnaires, and they could quit the study at any time. After finishing the questionnaire survey, each teacher could get a small gift as a reward.

We used SPSS 22.0 to conduct the correlations, descriptive statistics, and Cronbach’α coefficients for the main study variables. Mediation analysis and moderated mediation analysis were conducted using SPSS PROCESS. We used a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples to assess the unconditional indirect effects, which were considered significant when the 95% bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (95% CI) does not contain zero.

Means, SDs and Pearson correlations of the main study variables are presented in Table 1. The results showed that effort-reward imbalance was significantly correlated to occupational well-being (r = −0.42, p < 0.001), psychological capital (r = −0.33, p < 0.001) and emotional exhaustion (r = 0.61, p < 0.001). Emotional exhaustion was significantly correlated to teachers’ occupational well-being (r = −0.65, p < 0.001) and psychological capital (r = −0.55, p < 0.001). Occupational well-being was significantly correlated to psychological capital (r = 0.59, p < 0.001).

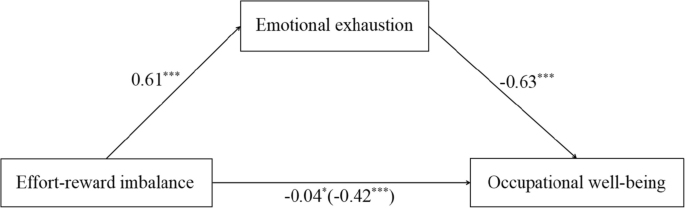

The mediation analysis of emotional exhaustion was conducted using model 4 in SPSS PROCESS. The demographic information(teachers’ gender, age, teaching experience, educational background, and income) were included as control variables during the mediation analysis. The results (displayed in Fig. 2 and Table 2) showed that, effort-reward imbalance had a significant negative effect on occupational well-being (β = −0.42, p < 0.001), after adding emotional exhaustion in the model, effort-reward imbalance also negatively predicted occupational well-being (β = −0.04, p < 0.05). Effort-reward imbalance also significantly predicted emotional exhaustion (β = 0.61, p < 0.001), and emotional exhaustion negatively predicted occupational well-being (β = −0.63, p < 0.001). The results showed a significant indirect effect from effort-reward imbalance to occupational well-being through emotional exhaustion, the effect size was −0.38, 95%CI [−0.41, −0.35].

After testing the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion, we also tested the moderating effect of psychological capital in the mediation model using Model 8. The 95%CI does not contain zero means the moderated mediation effect is significant. Before testing the moderated mediation effect of psychological capital, we tested the effect from effort-reward imbalance to emotional exhaustion and occupational well-being excluding the interaction term, the regression result from effort-reward imbalance to emotional exhaustion was β = 0.4706, t = 33.8229, p = 0.000, 95%CI[0.4433, 0.4979], the regression result from effort-reward imbalance to occupational well-being β = −0.0340, t = −2.0460, p = 0.0408 95%CI[−0.0666, −0.0014]. The effects from effort-reward imbalance to emotional exhaustion and occupational well-being were all significant, and then we conducted the moderated mediation analysis.

The results (see Table 3) showed that psychological capital had a moderating effect on the direct effect of effort-reward imbalance on occupational well-being (β = 0.03, t = 2.12, p < 0.05, 95%CI [0.01,0.06]), and the effect of effort-reward imbalance on emotional exhaustion(β = 0.03, t = 2.06, p < 0.05, 95%CI [0.001, 0.051]). So, the results showed that the moderated mediation effect was significant, teachers’ psychological capital moderated the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being, effort-reward imbalance and emotional exhaustion.

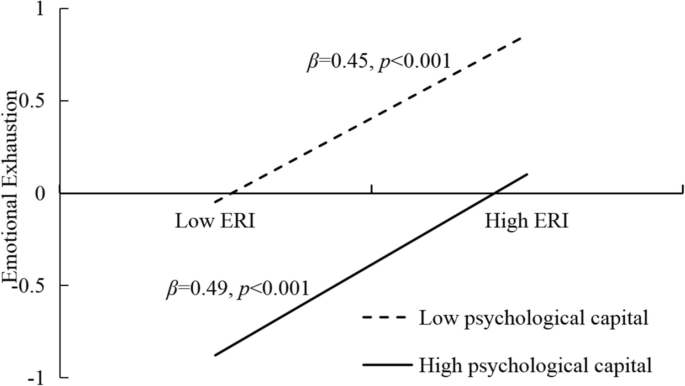

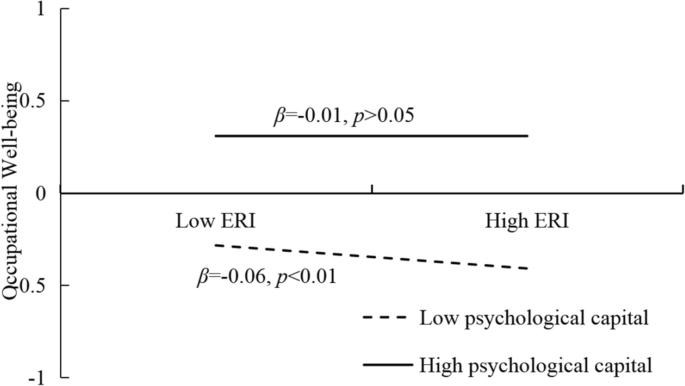

To better understand the interaction effect of psychological capital, we also conducted the simple slopes analysis. The result showed that (see Fig. 3 and Fig. 4), for the moderating effect of psychological capital on the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and emotional exhaustion, the predictive effect of effort-reward imbalance on emotional exhaustion at high level of psychological capital(simple slope = 0.49, SE = 0.02, t = 26.82, 95% CI[0.45, 0.53]) was higher than the effect at low level of psychological capital (simple slope = 0.45, SE = 0.02, t = 25.91, 95% CI[0.42, 0.49]). For the moderating effect of psychological capital on the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being, the predictive effect of effort-reward imbalance on occupational well-being at low level of psychological capital(simple slope = 0.49, SE = 0.02, t = 26.82, 95% CI[0.45, 0.53]) was higher than the effect at high level of psychological capital(simple slope = −0.01, SE = 0.02, t = −0.04, 95% CI[−0.05, 0.04]). The results indicated that teachers’ high level of psychological capital could buffer the negative effect of effort-reward imbalance on their occupational well-being and emotional exhaustion.

the moderating effect of psychological capital on the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and emotional exhaustion. Note: ERI = Effort-Reward Imbalance

the moderating effect of psychological capital on the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being. Note: ERI = Effort-Reward Imbalance

This study examined the relationship between Chinese rural preschool teachers’ effort-reward imbalance and their occupational well-being, and the effect of emotional exhaustion and psychological capital. The results revealed that, effort-reward imbalance was significantly negatively related to occupational well-being; emotional exhaustion mediated the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being; psychological capital moderated the mediation model, that is high level of psychological capital not only buffered the direct effect from effort-reward imbalance to their occupational well-being, but also buffered the indirect effect from effort-reward imbalance to their occupational well-being through emotional exhaustion.

This study found that the effort-reward imbalance of rural preschool teachers was significantly negatively related to their occupational well-being, which confirmed hypothesis1. The results was similar to previous study on psychiatric nurses [66, 70], which found that effort-reward imbalance impact their general well-being. This study found the negative effect of effort-reward imbalance on the occupational well-being on the group of rural preschool teachers, which was of great value to promote the occupational development of preschool teachers. In China, preschool teachers need to put in more efforts to meet the diversified needs of children, but they receive lower rewards, such as an unsatisfactory salary and limited career development [18]. A high level of effort-reward imbalance will also increase the risk of individual’s negative emotions and stress-related diseases [49]. Furthermore, empirical research has found that the pursuit of professional development is highly correlated with occupational well-being [41]. Due to the imbalance in educational resources between urban and rural areas, professional development opportunities among rural teachers are relatively few and of low quality. In result, the professional development path of rural preschool teachers is usually not as smooth as that of their urban counterparts [61]. As a profession characterized by heavy workloads, low return on investment, and weak social support, preschool teachers are prone to job burnout, which negatively impacts their work engagement [64]. Therefore, the effort-reward imbalance of rural preschool teachers could affect their occupational well-being negatively.

This study found that emotional exhaustion plays a mediating role between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being of rural preschool teachers, which confirmed hypothesis 2. That is to say, rural preschool teachers who experience a high degree of effort-reward imbalance are more likely to feel emotional exhaustion, which in turn reduces their occupational well-being. Previous study have found that work-life imbalance of college teachers could affect their occupational well-being through emotional exhaustion [59]. Our study focused on preschool teachers, who are more prominent of work-family imbalance than teachers at other educational stage [19]. So, this study clarified the influencing mechanism from work-family imbalance on their occupational well-being from the perspective of emotional exhaustion. In addition, the results also consistent with the Conversation of Resources Theory, which states that stress is mainly caused by the depletion of resources and the failure to obtain a corresponding return on a large amount of resources [23]. When teachers feel effort- reward imbalance, they have to spend more effort and resources to complete tasks, subsequently experiencing higher work stress, which can lead to emotional exhaustion [32]. Emotional exhaustion arises as a chronic consequence of prolonged emotional labor in interpersonal interactions, particularly in professions involving intensive emotional engagement [38]. For preschool teachers, this manifests through extensive emotional demands during daily interactions with young children, parents, and colleagues [69]. Their work necessitates continuous balancing of internal emotions and external expressions to meet professional expectations [45]. Emotional exhaustion, as the core dimension of job burnout, directly depletes individuals'emotional resources and psychological energy [39]. Research indicates that emotional exhaustion is the most prominent form of burnout among rural preschool teachers, leading to a lack of engagement, reduced enthusiasm for work, and negative work attitudes [65]. When rural preschool teachers experience prolonged emotional exhaustion, their emotional regulation capacity significantly deteriorates. This leads to the accumulation of work-related negative emotions (e.g., frustration, apathy), reduced job satisfaction, manifestation of burnout symptoms, and ultimately diminished occupational well-being [66, 67, 70].

First of all, psychological capital played a moderating role between the effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being of rural preschool teachers. Specifically, it mitigates the detrimental effect of effort-reward imbalance on their occupational well-being, thereby validating hypothesis 3. This result is consistent with the theory of Psychological Capital, which holds that psychological capital can alleviate individual’s occupational stress and improve their occupational well-being [34]. High levels of psychological capital mean that individuals are able to exhibit positive psychological states in the face of challenges, providing psychological resources to cope with challenges and mitigate negative emotional experiences [11]. Compared with rural preschool teachers exhibiting lower level of psychological capital, those with higher psychological capital demonstrate more proactive attitudes when confronting effort-reward imbalance. They actively adjust their mindset and behaviors to mitigate its negative effects [18]. Rural preschool teachers with higher psychological capital actively appraise their teaching competencies to cultivate self-efficacy, thereby playing a pivotal role in alleviating job burnout and enhancing occupational well-being among rural preschool teachers [66, 70]. Therefore, rural preschool teachers with high level of positive psychological capital can adjust their physical and mental state in the face of effort-reward imbalance, work actively, and feel a high level of occupational well-being.

Secondly, this study also found that psychological capital moderated the relationship between effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being through emotional exhaustion which also confirmed hypothesis 3. That is, compared with rural preschool teachers with lower levels of psychological capital, teachers with higher levels of psychological capital, the indirect effect from effort-reward imbalance to occupational well-being via emotional exhaustion was lower. According to the Conversation of Resources Theory, individuals strive to obtain and preserve resources, the loss and threat of potential and actual resource can cause feelings of tension and stress [23]. Psychological capital is associated with positive attitudes such as confidence and self-efficacy, which help to mitigate negative emotional experiences. In addition, individuals with higher levels of psychological capital are more likely to maintain their work ethic and rejuvenate in the face of adversity [4]. Preschool education requires high quality interactions with young children and meeting their diverse needs, which can easily lead to emotional exhaustion and negatively impact their well-being [3]. For rural preschool teachers, the lack of support from the external environment can lead to an effort-reward imbalance, further depleting internal psychological resources [64]. When external resources are limited, while it is also difficult for individuals to change, individual psychological capital becomes an important factor in compensating for resource exhaustion [24]. A high level of psychological capital enables preschool teachers to acquire sufficient psychological resources to overcome work difficulties and increase work engagement, thus buffering against individual’s emotional exhaustion [44]. Forthermore, high levels of psychological capital tend to exhibit greater self-efficacy and optimism, which can supplement resources to cope more effectively with job stress and challenges, thereby reducing the risk of emotional exhaustion and then improve their occupational well-being [18].

(1) The effort-reward imbalance of rural preschool teachers was negatively related to their occupational well-being; (2) Rural preschool teachers'effort-reward imbalance could affect their occupational well-being indirectly through emotional exhaustion; (3) Psychological capital moderated the direct path from effort-reward imbalance to occupational well-being, and also moderated the indirect path from effort-reward imbalance to occupational well-being through emotional exhaustion. That is, a high level of psychological capital can alleviate the direct negative effect from effort-reward imbalance to occupational well-being, and also alleviate the indirect negative effect on occupational well-being through emotional exhaustion.

These findings not only extend the effort-reward imbalance theory and enrich the research on occupational well-being, but also demonstrate the important value of psychological capital in improving rural preschool teachers'occupational well-being. In particular, we clarified the mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderating role of psychological capital. As an important part of China's basic education, the improvement of rural preschool teachers'occupational well-being is directly related to the quality of rural preschool education and children's development. Therefore, education administrators and policymakers should pay more attention to the effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being of rural preschool teachers. Firstly, policymakers should increase financial investment in rural preschool education, improve teachers'treatment and working environment, and enhance the social status and professional attractiveness of rural preschool teachers. Special training programs should be formulated for rural preschool teachers to improve their professionalism and teaching skills, taking into account their psychological health needs. Secondly, kindergarten managers need to organize regular teacher training and exchange activities to improve teachers'professionalism and psychological quality, as well as their ability to cope with work pressure. A more scientific and comprehensive teacher evaluation system should be established which not only focuses on teaching outcomes but also on teachers'efforts, work attitudes and mental health. Finally, rural preschool teachers should also improve their own psychological resilience, and the ability of emotion regulation to cope with the pressures and challenges of the workplace by providing opportunities for teachers to participate in mental health training programs and build positive interpersonal networks.

In addition, there are also some limitations in this study. Firstly, this study used cross-sectional research to collect data, which cannot strictly explain the causal relationship between variables. So the longitudinal research design could be adopted in future research. Secondly, the data of this study are all teacher report, which may not reflect the real situation of rural preschool teachers. In future studies, multi data sources can be used to obtain more objective research data. Thirdly, due to the occupational characteristics of preschool teachers group, the sample size of male teachers and female teachers is not balanced, which make it difficult to explore the gender difference of the model. Future studies can pay more attention to the differences of male and female teachers in effort-reward imbalance, and how these differences affect the development of preschool teachers'occupational well-being.

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

We thank all the preschool teachers participated in this research.

This study was funded by the Humanity and Social Science Youth Foundation of the 21 Ministry of Education in China (Grant Number: 22YJC880081), Educational Science Planning project of Zhejiang Province (Grant Number: 2023SCG038), Research project of Zhejiang Federation of Social Sciences (Grant Number: 2025N176).

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Huzhou University. The ethical review approval Code:2023, No. 40. All participants read the objective statement of the investigation and signed informed consent.

Before the data collection, we provided informed consent to all teachers participated in the study, which mainly included a brief description of the study content and purpose. Participation in the study was completely voluntary and participants could quit at any time. Any information provided by the participants will be kept strictly confidential and used only for research purposes.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Wang, Y., Gu, L., Jin, M. et al. The relationship between preschool teachers’ effort-reward imbalance and occupational well-being in Chinese rural areas: a moderated mediation model. BMC Psychol 13, 722 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-03081-5