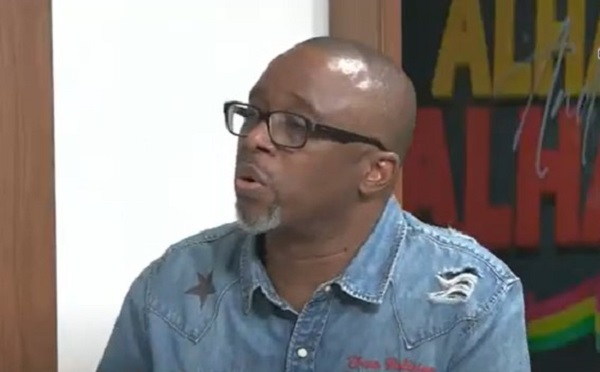

The Man Behind Colorado Springs' Ford Amphitheater

The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

in Colorado Springs’ Briargate neighborhood, JW Roth’s office offers a stunning view of Pikes Peak. Or, at least, it usually does. On this overcast February day, the main attraction isn’t the mountain hidden behind the haze of clouds, but rather the massive vinyl collection displayed around the room. Albums line the walls and span a variety of genres and artists, from the Beatles to Bob Seger to Willie Nelson. And these are just a fraction of the 3,000 LPs Roth has amassed over the years.

“They would be a lot more valuable, too, if I had known back then what I know now,” he says with a chuckle. His records bear telltale rings on their jackets, suggesting they’ve been played and replayed. Elsewhere, though, there’s plenty of mint-condition memorabilia, including the piano Ryan Tedder wrote OneRepublic’s megahit “Apologize” on and a guitar Taylor Swift signed before her debut album hit the airwaves.

If the well-worn vinyl is evidence of the 61-year-old businessman’s decades-long obsession with music, the pricey collectibles reveal that his passion has not changed with age—but his bank account has. Roth parlayed his success as the co-founder of a Castle Rock–based biopharmaceutical company in the early 1990s into a prepared foods venture, real estate development, and a venture capital fund. He’s made enough money to coast through retirement.

Instead, over the past decade he’s sunk a large fortune into Venu, an entertainment and hospitality company that owns Colorado Springs’ Phil Long Music Hall, Bourbon Brothers Smokehouse & Tavern, and Notes Eatery. He bought and, in April, resold both the Colorado Springs Business Journal and the Colorado Springs Indy, a biweekly paper founded in 1993 as a progressive counter to local conservative media. (In a statement announcing the sales, Roth and his business partner, who owned the papers for 14 months, said “it became increasingly challenging to communicate their vision and values through the platforms as they had intended.”) Most notably, though, Roth is the driving force behind Ford Amphitheater, a multimillion-dollar outdoor concert venue that opened in Colorado Springs this past August.

Like iconic Red Rocks Amphitheatre near Denver, Ford takes advantage of the splendor of its surroundings: Located just five minutes up the road from Roth’s Briargate office, it boasts the same unobstructed view of Pikes Peak. But while the 8,000-capacity Ford (9,500, if you count the events center Roth added) can’t match Red Rocks’ legacy, it tries to make up the difference with lavish amenities, including five rooftop bars that overlook the Rocky Mountains, a state-of-the-art sound system, and firepit suites that glow in the night.

“Music is a memory,” Roth says. “I look back on some of my first concerts, and my buddies and I were sneaking shooters in our boots because that was all we could afford. Even if the car broke down or it rained or snowed, those nights with my friends were some of the best nights of my life. Even now, I might hear a song going down the road, and I’m right back there. That’s what I want to give people.”

about his first shows or the disasters that befell him and his friends on their way there. The only time his momentum sputters is when he’s ruminating on his childhood. “I grew up in a family where we didn’t have a lot of money,” he says. “For me, going to a concert required climbing a fence.”

Roth and his two siblings lived on the family’s ranch near Larkspur, where they helped their father, who also worked as a claims adjustor, with the livestock. It was a happy but narrow life. “You’d leave home, you’d get a job, and that was just the way things worked,” he says. Short on cash, Roth dreamed up various business schemes: selling chokecherries on the highway, hawking firewood. He left high school during his junior year, opting for his GED and a quicker route to the real world. What followed was a string of swings and misses, including a grocery delivery company that was perhaps a few decades too early.

He took odd jobs to pay the rent. He did a gig at a food distribution plant and another selling ranch supplies. In 1987, he joined the Denver Police Department and served for four years. “I loved every second of it,” he says.

But he never stopped thinking of himself as a businessman. At a networking event in the late 1990s, he met a couple of Denver-area entrepreneurs who were launching AspenBio, a biopharmaceutical company focused on developing drugs and diagnostic tests for livestock and other animals. They recognized in Roth a man who could serve as an intermediary between investors and scientists. With his background in ranching plus his gift of gab, he could explain in layman’s terms the benefits of, for example, a patented bovine pregnancy test called Sure-Bred. The businessmen asked him to join their company as a co-founder.

Roth’s son, Mitchell, remembers going with his dad on work trips to New York City. Dressed in a brown suit and matching tie from Walmart, the 10-year-old would attend breakfast and dinner meetings and everything in between. “I didn’t understand the nuances of what was going on,” Mitchell says, “but we’d leave the meeting to go have lunch somewhere, and I’d pepper him with a million questions, and he’d walk me through all of it.”

When Roth sold his stake in AspenBio in 2004, he used the profits to invest in packing plants and other agricultural enterprises. Eleven years later, he founded Roth Brands in Colorado Springs, which he’s come to consider his hometown. The company makes prepared foods for brands such as Prep Chef, Ioli, and Whole30, for which it owns the licensing rights. He also started developing real estate in Colorado Springs, where, in 2014, he opened Bourbon Brothers Smokehouse & Tavern. Roth hoped to lease the space next door to a pie shop. When that deal fell through, he turned it into a midsize music venue now called Phil Long Music Hall.

Being around live music again was exciting for Roth. He and his wife later attended a concert at a Napa Valley winery’s amphitheater. Roth was hooked. He returned home and told Mitchell, now the CEO of Roth Brands, that he planned to build a massive amphitheater, something big enough to turn Colorado Springs into a cultural destination. “I was thinking to myself, Oh, my God, have we even made money on the hall yet?” Mitchell says. At the same time, Mitchell wasn’t surprised: “He’s missing that filter that stops most people from going all in on a crazy idea.”

Roth spent countless summers with friends camping out in front of Gart Brothers, a downtown Denver sporting goods store that sold concert tickets. They waited, rain or shine, to see REO Speedwagon, Journey, the Eagles, and the Rolling Stones at Red Rocks or Folsom Field in Boulder. “We were standing in line trying to get lawn tickets or nosebleeds, going to six or seven shows a summer,” Roth says. “We had nothing else to compare it to, and we just loved being there.”

As much as Roth loved live music, he didn’t love music venues. “Most venues are not music-centric,” he says. “They’re built for something else entirely, whether that’s hockey or baseball or football.” With the help of BCA Studios, an architectural firm based in Atlanta, he began sketching out plans for an amphitheater that would be designed—both acoustically and visually—for music, but he quickly realized his dream would cost upward of $100 million. “I sat down with my family and said, ‘Look, I hope you guys plan on being successful, because your dad might blow your inheritance,’ ” he says.

Fortunately for his three children, Roth didn’t go broke building his Xanadu, thanks to a novel financing idea that came from his own backyard. In 2020, Roth had constructed a six-foot-by-40-foot firepit at his home. Friends and family loved gathering around it to hang out and listen to music. Why not bring a spark of that to his new amphitheater?

In lieu of traditional suites, he decided his venue would have 92 outdoor firepits that accommodate from four to 10 fans each and include access to premium food and drinks, priority parking, and dedicated restrooms. More important, they would pay for themselves: Rather than opting for the traditional model of renting suites by the year, Roth sold his firepits for $250,000 each, making the buyers part-owners in the amphitheater. “I took an ad out in the newspaper and shot a 60-second commercial that was on TV every night during the news talking about these firepits,” he says. “In 14 weeks, I sold $50 million worth of them.” A naming-rights deal with Colorado Ford dealerships also helped cover the total $130 million price tag.

Ford Amphitheater hosted its first concert, Tedder’s OneRepublic, this past August. Built for the modern concertgoer, the venue offers three rideshare-specific drop-off and pick-up lanes. The lawn has technology that keeps the grass—and any attendees lounging on it—cool on hot days. Cutting-edge, German-made satellite speakers installed throughout the facility ensure that every seat is immersed in sound.

Ford ticket prices start at $48 for the lawn and max out at $237. Red Rocks tickets, by comparison, range from $46 to $465. “I never want to forget the kid I was at 16 years old,” Roth says, “and I want to make sure that kid and his girlfriend can come and enjoy the show.” They’re able to because of the firepits, which essentially subsidize the rest of the seating.

They’re also pretty. When Tedder first looked out from the stage this past summer, he told the crowd that the glow of the fires in the audience had transported him halfway around the world: “I’ve never seen anything like this. I feel like I’m in Abu Dhabi or something.”

In addition to OneRepublic, Ford Amphitheater hosted the Beach Boys, Ivan Cornejo, and Robert Plant and Alison Krauss during its inaugural season. “This venue is already supporting local businesses, with many reporting an increase in sales on concert nights [that] I expect will grow exponentially,” Colorado Springs Mayor Yemi Mobolade says. He thinks Colorado Springs is now a competitor for major concerts and events that would have gone to Denver in the past. Some in Colorado Springs, however, hope they still will.

Prior to Ford’s construction, the city granted Roth a hardship permit that allows the venue to exceed noise limits, and Roth says he went $30 million over budget in part to add parking spaces and a sound wall to appease neighbors. Nevertheless, OneRepublic garnered 140 noise complaints on the amphitheater’s opening night. “I have to live with bass and noise that comes through my walls…while I’m trying to fall asleep,” a local resident told a Colorado Springs TV station this past December.

An independent study commissioned by Colorado Springs found the venue did not exceed the limits set in its permit. Still, after several months of City Council meetings and listening sessions with residents, Roth’s company, Venu, entered into an agreement in January to implement additional sound-mitigation measures, including a noise-monitoring station and changes to the speaker system. Both are scheduled to be completed this year. “When I started out here, the city wasn’t my partner, so I didn’t think about holding neighborhood meetings or going through that process,” Roth says. “But I’ve worked very hard to be a good neighbor, and sometimes you’re just going to get pushback. It’s a big change for some people, but vibrant cities have a vibrant culture and a vibrant sound.”

Roth is now focused on expanding Venu’s lineup by building a network of 20 similar amphitheaters around the country. Construction is already underway in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma; Oklahoma City; El Paso, Texas; and McKinney, Texas. At each spot, Roth made sure to include the local government in his plans from the start—and not only to silence noise complaints.

Like Ford, each new amphitheater is funded in part through firepit suites. But Roth is also following the examples of two of his business heroes: Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, and George Steinbrenner, the late owner of the New York Yankees. Both used public-private partnerships to pay for stadiums.

In 2015, Frisco, Texas, contributed about $115 million to land the Cowboys’ $1.5 billion headquarters and training facility. Roth brought on Frisco’s then-mayor, Maher Maso, to help Venu broker similar deals in each of its intended markets. McKinney alone has earmarked $110 million in tax incentives for what will be Venu’s largest project, a 20,000-seat amphitheater. In return, the city projects the development will generate roughly $3 billion for the area over its first decade.

Venu’s plans are ambitious, but they’re also filled with promise for the cities—and for the music-loving entrepreneur who continues to gamble on himself. “I always had a vision, growing up, of the type of businessman I wanted to be, but that wasn’t really an option in the family I grew up in,” Roth says. “I had bigger ideas. I wanted to build things, create things.” Finally, the world is his stage.