An indisputable icon of the celluloid, revered for his bravura performances and infectious charisma, Al Pacino’s identity has become an inextricable element in the canon of American cinema. In a career spanning more than half a century, Pacino has cultivated an enviable track record, working with greats like Francis Ford Coppola, Sidney Lumet, Martin Scorsese, and William Friedkin, to name a few of cinema’s wizards, and producing some of the most excellent performances ever put on screen.

Born Alfredo James Pacino, the South Bronx native started honing his acting chops in theatre before taking the leap into cinema with a small role in “Me, Natalie” (1969). He next surveyed the life of a person with a heroin addiction in “The Panic in Needle Park.” He would then go on to play one of the most popular characters in cinema in “The Godfather,” shooting him to superstardom – all at thirty-two, with two film credits under his belt.

A quick look through Pacino’s career reveals a stunning assortment of machismo characters. From a sleazy Cuban drug lord in “Scarface” (let’s forget about Dunkaccino) to a hardboiled detective in “Heat,” Pacino is a natural chameleon, unafraid and daring in his choices. His career is equally fascinating, peaking in his first few films, maintaining that success with unconventional roles through the 70s, maturing in the 80s with the same indomitable force of the previous decade, winning an Academy Award in the 90s, solidifying his status as a cinematic legend in the new millennium, and making a splash during the last decade with “The Irishman,” Al Pacino is a movie star in the truest sense. Pacino is among the numerous faces of the Hollywood New Wave, sharing a seat in the pantheon with Robert De Niro, Robert Redford, and Dustin Hoffman, forever changing the cinematic landscape.

Pacino’s demeanor is worth a million words – it’s electrifying to observe, captivating in its unpredictability and wholly naturalistic. His expressions have distinct volatility, a fluidity quite hard to emulate because of his unmatched charisma. His effortless swagger, steely-eyed gaze, slim frame, and distinctive scruff in his voice all casts an unshakeable spell on his viewers. And he wields power conservatively, with intention, for an effect like any other. Here are ten of Al Pacino’s best performances:

“Glengarry Glen Ross” has an ensemble cast like no other – Jack Lemmon, Alan Arkin, Ed Harris, and Jonathan Pryce, to name a few, who lock horns in this riveting drama. Adapted from David Mamet’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, James Foley directs the heart out of it. The film goes between a few locations but mainly focuses on a real estate office. A senior agent threatens the agents of Mitch and Murray; all but two of the top salespeople will be fired by the end of the week. The game is set. What happens next is a back-stabbing catastrophe that’ll wring every ounce of empathy out of you.

Words are weapons in this film. Each character is armed with an arsenal of dialogue. From serious spats to casual confrontations, each actor is given ample time to shine, and Pacino shines like a knight in the wordy warfare. Exploiting his theatre abilities, Pacino essays the manipulative Richard Roma, one of the top closers fighting to close the ‘better’ leads. His monologue exposes our own human instinct for self-preservation, denying empathy and affection for his colleagues, striving to make it in his profession even if it means throwing someone under the bus. Roma is a cool cat, but that doesn’t mean he will let things slide. Pacino channels his charisma into an ice-cold and confident aura that defines and justifies his place in this drama of excellent actors. It’s such a small role, but Pacino knocks it out of the park.

A quiet film in the canon of wiseguy cinema, “Donnie Brasco” hits all the beats of a very Italian-American crime story but also gleams a certain humanity. An empathetic albeit gritty portrait of everyday life in the underbelly of the New York mafia, there is a sense of maturity that is equally serious and bittersweet. A small-time jewel thief played by a formidable Johnny Depp, Brasco’s first encounter with aging hitman Lefty Ruggiero, played by Pacino, is when he is asked to check if Lefty’s diamond ring is a fugazi. They beat up the man who had given them a fake ring and take his car as collateral. This was Brasco’s initiation into the Bonnano family, where Lefty is an enforcer. Brasco learns the ropes, the tricks, and the trade of the mafia and develops a closeness with Lefty.

The problem? Donnie Brasco is not real, but the fake identity of undercover cop Joseph Pistone. Depp and Pacino exude dizzying levels of charisma on screen. They sell the chemistry well. We learn so much through Lefty’s role as a mentor. The synergy of their performances is in their understanding of their characters – simple, stoic, and suffering from very relatable problems. There’s something quite tender in Pacino’s performance here. His ability to transform and switch personalities goes unnoticed.

He stands tall as Lefty, the notorious mafioso, and in the next scene, you feel pity for this tracksuit-wearing, washed-out father of a junkie, straddled with debt and struggling with irrelevance. Lefty and Brasco’s relationship, a close approximation of a father-son bond, becomes a dilemma in which the film centers. Pacino is quietly powerful here; even in a two-man show, it’s obvious who’s the real deal on screen.

“Carlito’s Way,” coincidentally, starts like a mix of Sidney Lumet’s “Serpico” and De Palma’s previous venture with Pacino, “Scarface.” Our protagonist is grievously hurt, popped in the subway station, and he’s taken out on a stretcher. He monologues how he’s ended up here and looks up at a sign written ‘Escape to Paradise.’ The central theme of “Carlito’s Way,” explained in the opening, is one’s inability to escape one’s past and their affinity towards self-destruction. “Carlito’s Way” is a provocative gangster drama, a giallo-colored, neon-heavy, and stylish story of a man who must battle his past if he needs a chance to live in the future. Carlito Brigante is a Puerto Rican ex-convict with a big mouth.

He’s freed from a thirty-year life sentence after five years in prison by his lawyer friend. Carlito wants to abandon his criminal past, but he’s pushed into one more drug deal before he can leave it for good. But that’s not the end of it. Each character is an exquisitely colorful and exciting plot point with whom Carlito can interact. It’s brilliant writing. Pacino is effortlessly suave here, possessing an oomph that’s fun to just observe. Brian De Palma has the sauce, not like he didn’t, but in “Carlito’s Way,” it’s even more observable. Each action set piece is a playground for Pacino to improvise. Sex and action are incredible moments for stylistic imposition, and Pacino understands the assignment properly.

“GOD HELP BOBBY AND HELEN”: written in bold, black letters above a grainy still of the lovers embracing, the original poster for “The Panic in Needle Park” encapsulates everything: the despair, the grime, the unseen horror of Bobby and Helen’s lives. But even amidst the troubles and suffering scattered like used needles and drugged bodies, love grows, persists, and emboldens itself to be a light of hope. They have each other; it’s not much, but beats nothing. It’s small but not insignificant, like the line below the plea to God in the poster, which says, “They’re in love in Needle Park.”

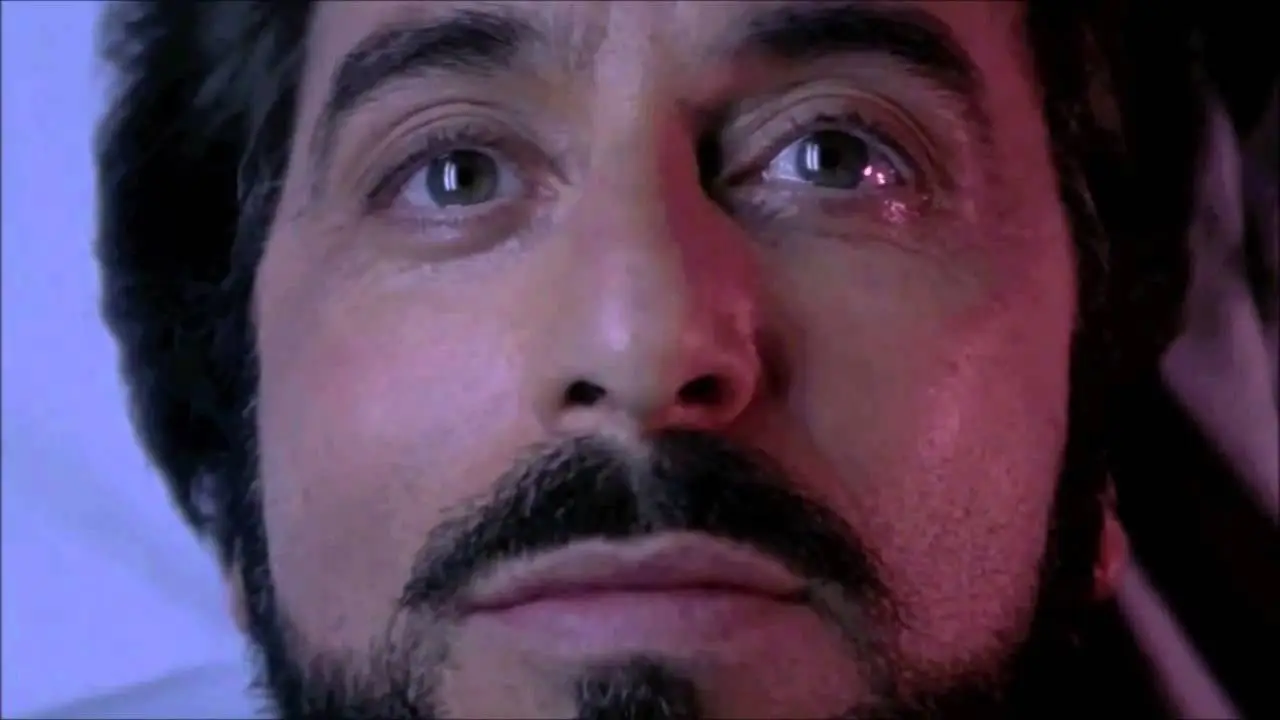

There’s nothing sexy or cool about drug addiction. Jerry Schatzberg insists on that point with his cinema-verite style. There are shots of heroin addicts shooting up; we see them stumble and suffer in real-time. It’s a tough watch, but what gleams from the sickly pale chaos of Needle Park is our two protagonists. Kitty Winn and Al Pacino are excellent to watch, giving hypnotizing, naturalistic performances. Winn won the Best Actress award at Cannes, and it shows. Pacino compliments her softness with a kinetic presence.

Baby-faced and big-eyed, Pacino balances between a teenager’s swagger and an adult’s seriousness. Their chemistry shines in the heroin-infested hellhole. Like a tame, spiritual ancestor of “Requiem for a Dream,” Schatzberg crafts an emotionally stirring drama that pulls the punches at the right time. Moreover, the film has a commendable screenplay by one of the greatest essayists of all time, Joan Didion, and her husband.

It’s an iconic line. It’s so iconic that I don’t even need to write it, and so iconic to the point where the very mention of “Scarface” and Al Pacino will invoke this line being said. Sure, it’s a little annoying, but blame it on Pacino’s gobsmacking, culture-defining, balls-to-the-walls portrayal of Antonio “Tony” Montana. The Cuban drug lord is a walking, mostly talking Hispanic stereotype. Ironically, it took an Italian-American New Yorker to pull it off. “Scarface” is a simple film, a rags-to-riches tale of a Cuban immigrant rising through the ranks of the mafia, his life as the top honcho in sunny Miami, and his eventual downfall. But at its core, it’s a classic story of man’s hubris, the pitfalls of the American dream, the superficiality and ephemeral satisfaction in the realities violence and wealth promises.

Tony Montana is a political prisoner who arrives in Miami in the Mariel boatlift. In exchange for a green card, Tony, with his friends, must assassinate one of Castro’s henchmen. This becomes his gateway into the underworld. Over the course of three hours, we hear expletives of varying creativity, rock to Giorgio Moroder’s banging soundtrack, see the glitz, the glamour, the drug-addled sights of the 80s, and bear witness to a man slowly but surely losing his sanity to the gushes of cocaine and power. Al Pacino is the man here, fun and memorable, full of the zest and antics that define Montana’s mythic personality. He doesn’t hold back, playing into the seriousness and absurdity of Montana’s neuroses with equal importance. The three-hour runtime is redeemed by his charisma, which is almost like a chokehold whenever he comes on screen. You just cannot take your eyes off of him.

Sidney Lumet holds a special place in American cinema. His films are unwittingly documentary-like, stylish in their contemporary methods, like detailed probings into socio-political brouhahas with realism-heavy narratives. “Serpico” offers one such cross-section of the 1970s American ethos, a timeless drama on bureaucracy and corruption and one man’s fight against the system. The film opens up with a man being transported to the hospital in a police car, his face all bloodied. It’s undercover cop Frank Serpico, and he’s been shot in the face. His fellow police officers get the news and believe it was one among them who did it. The film narrates what led to Serpico’s grievous affliction, from the day he graduated from the police academy to reporting on his sleazy colleagues.

Frank Serpico finds himself in a David vs Goliath battle against the state of New York. Rampant corruption and crime ran high in the 1970s, and “Serpico” is a reaction to injustice, a perfect liberal manifestation of the man-against system. It’s a transformative role, playing to Pacino’s strengths. Serpico’s idealism is systematically oppressed, so he naturally distrusts it. The growth of his character from an idealism-drunk police cadet into a paranoia-stricken officer is striking. Lumet also brilliantly conveys to us the passage of time with Pacino’s appearance. It’s sometimes over-the-top but mostly an energetic role. Pacino translates the real Serpico’s fear, distrust in the system, and subsequent redemption with convincing, near-realistic ease. Also, Pacino is a beautiful man.

It’s easy to identify a Michael Mann film: obsessive and self-destructive characters, urban architecture in all its twisted glory, modern malaise spiked with neon and asphalt dreams, cool punchlines, men, men, and more men, and heaps of style and interesting camerawork. But the Chicago-born filmmaker never falls into the trap of repetition. Mann’s filmography provides a series of highly original and human stories, autobiographical and fictional, aimed at flaying open the nuances, linkages, and contrasts of masculinity, technology, relationships, and global landscapes in the postmodern era. “Heat” is a crystallized vision of Mann’s own obsession with these themes. Put an unstoppable force against an immovable object, and it becomes the subject of the ultimate philosophical treatment.

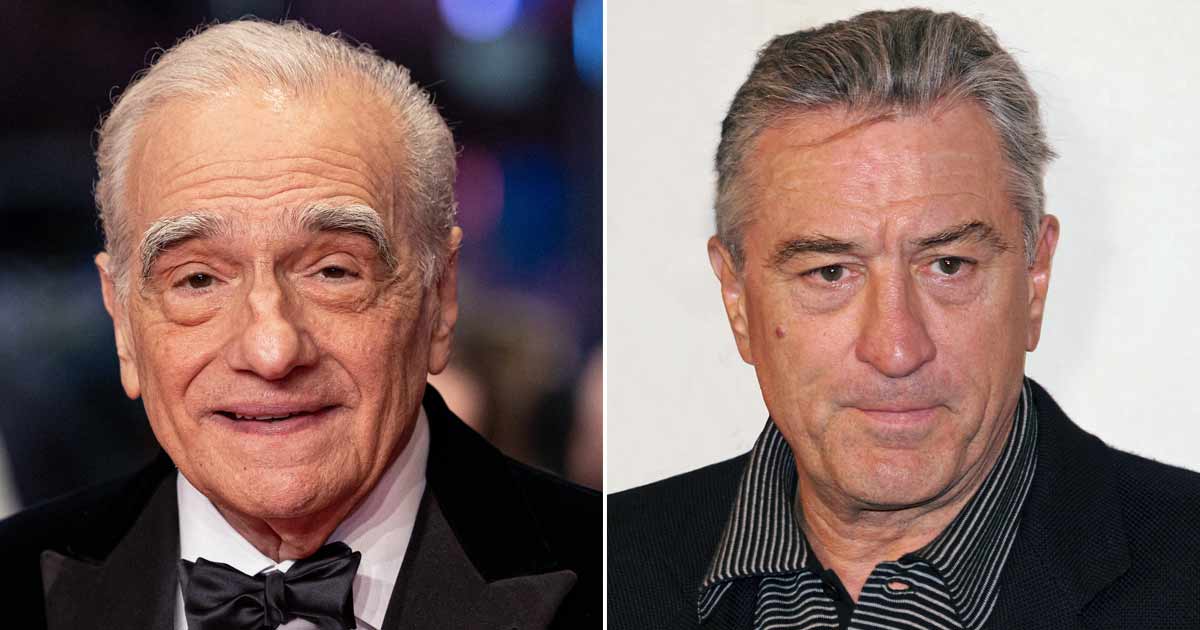

And who better to characterize them than two of the greatest actors in the world? It’s hard to say who the bad and good guys are; Mann structures it according to our subjective imposition. Pacino plays Vincent Hanna, a seasoned detective with an estranged wife and distant step-daughter. He investigates a robbery committed by Neal McCauley, a similarly isolated but methodic robber. It’s their conflict that defines the film. Pacino’s rendition of a talented but tortured detective is utterly brilliant – it has its moments of absurdity and anger, but overall, it’s a powerful role. Hanna’s personal and professional lives seep into each other, offering even more conflict. Robert De Niro’s Neal McCauley adds fuel to the fire while reflecting Hanna’s inner turmoil. It really sucks that the one person who understands you is also the same person you really hate.

Heavy is the finger that wears the family ring. “The Godfather Part II” sees Michael Corleone navigate deeper into the murky depths of the Italian underworld. Armed with his faith and intelligence, Michael sees himself questioning the loyalty that binds family, friends, and the mafia together. Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo get to the crux of the matter with a dual narrative, recounting Vito Corleone’s rise to power and Michael’s relentless quest to wipe out his rivals. “Part II” is a dense, despairing work of art with morally ambiguous characters and compelling narratives.

We see two lives living in different worlds: one of a new immigrant trying to make it big and a mafia boss trying to maintain his sanity. The contrast is blinding. Al Pacino’s Michael is devoid of the naivete and innocence in “Part II.” His gaze is ice-cold, and anger is seemingly brimming in his every word. There’s an ineffable darkness in his movement, lurking and moving like a snake ready to strike, but the power comes in his control to do so. Michael runs the mafia, like a business; connections become arbitrary and self-serving, and everything feels methodic and exact. “Part II” is the tragedy of Michael Corleone, his slow realization of himself as a villain, and wow, does Pacino fit the part!

It’s like watching a bad day get progressively worse, and just when you think it can’t possibly become worse than this, it does. Sustained chaos, masterfully maintained by Sidney Lumet’s direction and Frank Pierson’s screenplay, keeps the narrative fresh and exciting. Al Pacino and John Cazales, who tie and orchestrate this mess, act their hearts out as two amateur bank robbers, Sonny and Sal. Based on real-life events, the duo decided to rob a bank so Sonny (Pacino) could finance his partner’s sex reassignment surgery.

Things don’t fall according to plan, and Sonny and Sal (Cazales) have no choice but to hold up the bank. Tabloids and police arrive at the scene, and it’s a race against time for authorities to defuse the situation without putting the hostages in harm. Pacino is dynamite here; it’s like watching sodium metal react with water, a propulsive, hypnotizing performance, perfectly restrained, fizzing out on a bittersweet note. Thin-framed, wide-eyed, and potty-mouthed, Pacino (who has an uncanny resemblance with the real Sonny Wortzik) is exhilarating to watch fuck up. He’s sweaty, he’s sexy, and he can’t help himself swearing at cops and journalists. There’s an odd brand of humor in its premise, channeled by John Cazales, who’s level with Pacino in the quality of acting. It’s a demanding role, executed with finesse and absolute bravura.

There’s a scene in “The Godfather,” out of many brilliant ones, that stands out in terms of exposition and performance: Michael Corleone standing guard outside the hospital where his father is admitted. The atmosphere is tense. He’s on edge. Enzo, one of the Don’s henchmen, shivers in fear after a car passes by and shakily takes out a cigarette. The young Michael helps him light his cigarette, and he glares intensely at his own hands, steady and strong. Michael is unusually stoic. A faint realization sets in. He’s got the nerves to handle danger. Michael protested the idea of joining the mafia, but circumstances proved otherwise; like a moth drawn into a flame, Michael knows he has no other choice but to embroil himself in the underworld.

Al Pacino bases his performance on subtlety; it’s utterly professional in its execution. His eyes do the heavy lifting, and it’s in control of the scene. Expressions of horror, fear, confidence, and anger brims on the edges of his eyelids. We see his transformation from a simple young military man with his hushed voice and mousy frame into a terrifying mafioso. Pacino wrangles silence for the best effect; it adds tension in scenes when Michael contemplates, in terse confrontations, when he’s the only one who keeps his cool. Pacino’s screen presence is formidable, and the best scenes are when he shares the screen with the equally brilliant Marlon Brando. “The Godfather” might be known for the latter’s Academy Award-winning performance as Don Corleone, but Pacino’s Michael Corleone is the scene-stealer.