Substack Summer, AI Slop, and the State of Selling Books

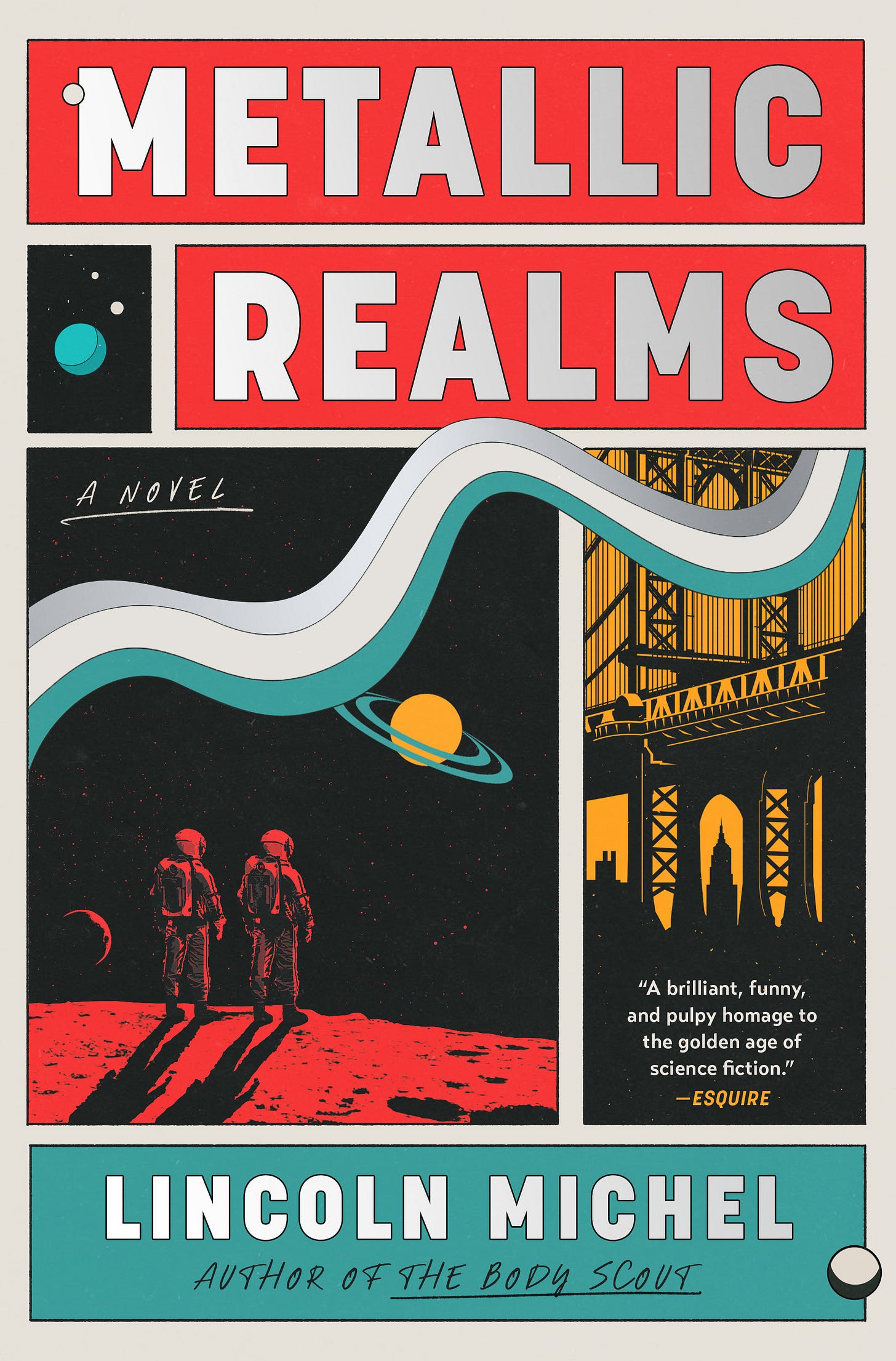

By now, everyone has discoursed extensively on the AI-hallucinated book recommendations that ran in newspapers like the Chicago Sun-Times and Philadelphia Inquirer. I contributed my own take on the increasing flood of GenAI slop. I won’t rehash that here. But outside of AI questions, the whole fiasco has got me thinking about the general state of book publicity and trying to sell novels—hey did I mention my new novel Metallic Realms was just released?—in the age of declining review column space, shrinking readership, and fractured social media.

Folks, it ain’t great.

(You may mentally add “he said, shocking no one” to the preceding sentence.)

Or at least the state of selling books is a period of flux. The old models of bookselling have largely fallen apart over the past few decades and supposed replacements (book bloggers! Wait, now book twitter! Oops, now BookTok!) sprout and quickly disappear like mushrooms after a storm. Today, the most positive development is probably this right here. By which I mean, Substack. Indeed, I was initially planning to write a post about what some writers here have dubbed “Substack Summer” where several literary Substackers such as

and

have novels out and

(who I think coined the term?) had her Substack-published novella raved about in a

New Yorker piece titled “Is the Next Great American Novel Being Published on Substack?”

Substack really has become important to bookselling. I increasingly get publicists pitching me about interviewing authors for Counter Craft. As a longtime Substacker whose novel was excerpted in the Substack magazine

and is getting reviews and interviews on Substacks, I can’t complain. Substack Summer seems good to me.

But maybe I’ll start with the bad news? The reason an AI slop book recommendation article could be run was because those newspapers, like countless other papers and magazines, no longer have book editors—much less dedicated book reviewers. Hell, newspaper staffs in general are shrinking. The reason this slop article was published is because these newspapers fill significant space with syndicated content they don’t produce themselves. Although authors love to complain about their publishers failing to do their part in selling books, the reality is the media landscape is rough terrain for literature. And the fact that even supposedly venerable papers are outsourcing more space to low-quality content generators—who themselves outsource to AI—is demoralizing. Perhaps especially to publicists, who really do want to sell your book.

The publicist

made this point in her response to the AI book rec article:

Book publicists are stressed, overworked, tired, and are asked daily if anything is happening for a particular title. We endlessly pitch with the hope that someone responds to our emails. We receive the brunt of complaints when there is lackluster media for a book, even though we have no control over how or if journalists cover it. When I see something like an AI-generated page of book coverage, I think, “Why am I even doing this for a living?” I’m sure I’m not the only one. I’m also sure that we’ll see something like this happen again.

(I understand authors’ frustrations with book sales, but authors shouldn’t misplace that anger toward publicists. My wife, a book editor, just said to me, “You should add in that publicists are people with a highly marketable skill who choose to take a pay cut to work in publishing.”)

Even if there was a lot of review space and journals did respond to publicity pitches, the number of books published each year grows and grows. Penguin Random House—the largest of the Big 5 imprints—apparently puts out 15k print books and 70k ebooks a year. The print number alone means well over 100 books a month. From one publisher. Across all the traditional publishers, including small presses and university presses, the total number of books published in America is somewhere between 500k and 1 million: let’s call it 700k. The self-publishing space is even bigger. That market surpassed 2.6 million new titles per year before GenAI programs allowed a dramatic increase in titles.

Basically, the math of publishing is very brutal.

I’ll speak personally. I’m a sometimes book critic who writes 1-2 professional reviews a year. On this Substack, I interview maybe eight authors each year. So, let’s say I “cover” 10 new titles a year. (I write about older books more frequently, because I mostly read older books.) OTOH, I receive maybe 12 unsolicited review copies a month (plus some I ask for) and as many as 12 publicity emails a day. This isn’t an insane amount, but it is far more than I can handle. Every author I interview or book I recommend is a book I read in full and enjoyed. You are always getting my honest opinion. But I can only read so many new books for a newsletter that is a part-time side hobby. I teach full-time, (theoretically) write fiction regularly, and also write pieces for other magazines. The only people who can devote time to sifting through a significant number of new books are full-time book reviewers. Basically none of those exist anymore, as the journalist and writer

noted recently:

7 full-time book reviewers for perhaps 700,000 new books a year (not even counting self-published work). The math speaks for itself.

Then again, maybe none of this matters as far as sales. As an author, I want to be reviewed. I care about criticism and want to impress my peers, etc. But, book reviews have marginal impact on sales. The not-so-secret secret is that people really don’t read book reviews. There are some devoted readers of The New Yorker and NYT and a couple other places. Mostly, readers don’t read reviews though. When I edited Electric Literature, one of the more trafficked literary websites, our reviews got a mere fraction of the clicks of basically anything else including (you guessed it) lists.

What does sell books? One thing is booksellers. If booksellers enjoy a book and feature it in their bookstores, it can really move units. Last year I was speaking to an editor after an author’s event and said I was sorry about a couple of high-profile negative reviews the book had received. The editor waved their hand. “Oh, it doesn’t matter. The booksellers love it and it’s selling really well.”

Beyond that? Who the hell knows. The safest way for a non-celebrity to sell a book is to, well, be a celebrity book club pick. That’s a crapshoot, and a game only a very narrow set of books can play. Subscription boxes are an increasingly big part of book selling. Otherwise, you can hope and pray to go viral on BookTok—although only a few genres of literature seem to ever go viral there. So, what’s left?

Well, here we can circle back to “Substack Summer.” I think Peter Barker was quite right to say in the aforementioned New Yorker piece:

There is, at times, an optimism in the digital air that recalls the early days of blogging and of Twitter, when both seemed to create new scenes relatively unencumbered by old hierarchies and blind spots: the types of places where a passionate amateur had what felt like a real chance of accelerating the process of becoming a name.

In terms of book sales, Substacks and other newsletters matter more and more. And why not? People have real and authentic conversations about books here. Readers routinely tell me that my articles made them buy a book, especially when it is an obscure or older book they weren’t familiar with such as my recent article on rediscovered German fairy tales from 19th century. There are surely some AI slop Substacks and plenty of human-written bad ones. But they are easy to filter. You get to pick and choose who to subscribe to. If you trust a writer—or the increasing number of interesting Substack literary magazines (sublit mags?)—then you know you are getting people’s real actual thoughts on what they are reading or thinking about. It won’t be ChatGPT hallucinations or paid publicity or mere regurgitations of whatever is going viral of BookTok. We’re all doing this on the side with minimal or no money attached. So, that’s good.

On the other hand, we have to be honest that Substack can’t replace traditional media coverage of books. That’s precisely because almost all of us are just doing this on the size with minimal or no money attached. To be a full-time book reviewer takes money, and there is never going to be enough of that to go around. Literary Substack is a small raft in a sea of indifference. And Peter Baker’s quote above carries with it the implication that Substack could fade as blogging did or be destroyed as Twitter was.

But, hey, for now it’s something.

If you like this Substack, please consider subscribing or checking out my new novel Metallic Realms. It is out in stores and getting great reviews: “Brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “I left this book feeling … assured of the future of storytelling” (The Masters Review), and “Just plain wonderful” (Booklist). You can also read an excerpt of the novel in the excellent Substack magazine The Metropolitan Review.