Recommendations for strengthening primary healthcare delivery models for chronic disease management in Mendoza: a RAND/UCLA modified Delphi panel

Recommendations for strengthening primary healthcare delivery models for chronic disease management in Mendoza: a RAND/UCLA modified Delphi panel

Primary healthcare (PHC) should be the cornerstone of equitable, efficient and high-quality healthcare in low- and middle-income countries. However, numerous challenges undermine its effectiveness in these settings.

To identify recommendations to improve PHC by integrating user preferences and provider capacity to deliver patient-centred and competent care in the Mendoza Province, Argentina.

Modified RAND Corporation/University of California, Los Angeles (RAND/UCLA) Delphi method.

Health system of the Province of Mendoza, Argentina.

32 public health experts from Mendoza.

Proposals were developed from secondary data, the People’s Voice Survey, an electronic cohort of people with diabetes, qualitative studies of users’ and professionals’ experiences and reviews of interventions in primary care.

Experts had to evaluate proposals according to five criteria selected from the evidence to decision framework (impact, resource requirements, acceptability, feasibility and measurability).

The 19 final recommendations emphasise policy continuity, evidence-based policy-making and standardisation of healthcare processes. Key areas include optimising healthcare processes, managing appointments for non-communicable diseases and ensuring competency-based training in PHC. Implementing performance-based incentives and improving financial sustainability were also highlighted. Other recommendations focus on the Digital Transformation Act, user participation in healthcare design and skills development for active engagement. Collaborative definitions of quality care, incident reporting systems and performance metrics are critical to improving healthcare quality.

This process provided decision-makers with contextualised information for health policy development. These interventions represent a step towards improving PHC, particularly chronic disease management, and provide a foundation for future regional research and health policy.

Data are available upon reasonable request. Not applicable.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), primary healthcare (PHC) should be the foundation of equitable, efficient and high-quality healthcare.1–3 However, many challenges hinder its effectiveness in such contexts.3–6 Fragmentation and segmentation within health systems, particularly in Latin America, exacerbate inequalities and impede access to essential services.7 The problem is worsened by the limited availability and poor quality of health services provided by public and social security-funded systems in LMICs.7 The private subsystem often serves, although inadequately, not only high-income but also middle- and low-income populations. Addressing these challenges will require concerted efforts to improve governance, enhance collaboration between subsystems and prioritise quality improvement initiatives.8 9

PHC can potentially improve population health outcomes through early identification and intervention in the disease process and through a coordinated provision of care.1 However, the conventional model, in which PHC is the primary point of contact for most health needs, is being challenged by urbanisation, more providers, unregulated private providers, shifts in epidemiology, an increase in expectations for highly effective care and users’ lack of trust in providers.1 2 10–19 In this setting, PHC does not always function adequately, resulting in hospitals treating patients with chronic conditions that could have been managed by primary care providers.2 12–15 Integrating PHC represents a significant change in the financing, management and delivery of health services, with barriers such as a preference for vertical, disease-based interventions over comprehensive approaches and fragmented health governance.13 16 20 21

Argentina, an upper-middle-income South American country with a population of 44 million, has a relatively advanced healthcare system but struggles with equity and efficiency in service delivery. The health system in Argentina includes three subsectors: public, social security and private. The Ministry of Health finances the public sector, and its primary beneficiaries are persons without health insurance, usually from lower socioeconomic groups, including 36% of Argentina’s population.22 23 The social security sector, covering 60% of the population, is grounded in the social insurance principle, which requires all employers and employees to pay for a trust fund. The private sector provides services to individuals of high socioeconomic status who may have different prepaid health insurance packages.22 23 Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) represent over 78% of the national disease burden, with cardiovascular diseases accounting for nearly one-third of NCD-related mortality. The National Ministry of Health has introduced the National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of NCDs to address these issues. However, the decentralised nature of Argentina’s health system places implementation responsibilities on provincial authorities, resulting in uneven outcomes across regions.24

Mendoza, a province in western Argentina with 2 million inhabitants and an area of 1 48 000 km², faces significant challenges in delivering effective PHC for chronic conditions. Its healthcare infrastructure includes 25 hospitals and 342 PHC centres across five health regions.25 Despite this network, chronic disease management remains suboptimal, with many cases that could be managed at the PHC level being treated in secondary and tertiary hospitals. Key barriers include patient concerns about PHC service quality, such as limited trust in providers, long waiting times and appointment scheduling difficulties, which drive over-reliance on hospital services.22 26 27 On the supply side, PHC providers face challenges such as insufficient training, limited access to medications and diagnostics, poor care coordination, fragmented referral pathways and inadequate follow-up systems. Over the past 8 years, Mendoza’s health authorities have collaborated with institutions like the Institute for Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy to improve chronic disease care through initiatives such as cardiovascular disease screening and cancer screening research. However, sustained improvements in PHC remain elusive, underscoring the need for strategic recommendations to enhance chronic disease management in Mendoza’s primary care system.

In 2022, the Ministry of Health of Mendoza province partnered with the Quality Evidence for Health System Transformation, a research network led by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, which focuses on strengthening health systems in low-resource settings through research-based interventions.28 This manuscript presents the results of a Delphi consensus process that developed a set of recommendations, including feasible, culturally tailored interventions and strategies, to strengthen PHC to deliver patient-centred, high-quality care. Building on the findings from previous phases, the Delphi process incorporated evidence and insights to ensure recommendations were practical and locally relevant.

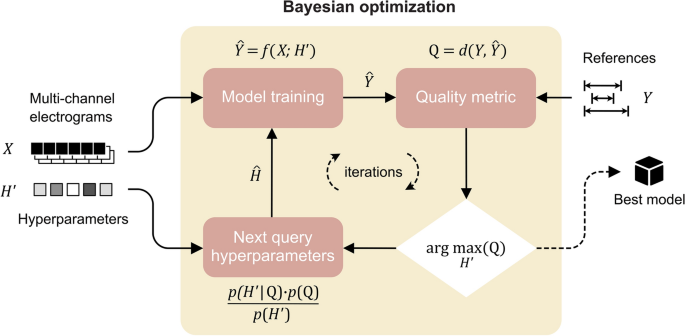

A modified Delphi RAND Corporation/University of California, Los Angeles (RAND/UCLA) method was used to build consensus.29 This method achieves consensus among experts or stakeholders on a particular topic through a structured and iterative approach. It is especially useful when face-to-face meetings are not possible. It also minimises the influence of dominant individuals and maintains anonymity. The method uses iterative rounds of feedback and revisions, allowing participants to re-evaluate their opinions by considering the collective input received in previous rounds. The modified method incorporates RAND/UCLA adequacy methodology elements, adding a structured approach to scoring and evaluating panel members’ responses, rigour and objectivity.29

First, a steering group composed of researchers, members of the Ministry of Health and a small group of experts evaluated the findings from the previous studies conducted in the province, which assessed the health system.

Previous studies leading to this consensus process included components aimed at assessing healthcare utilisation patterns, patient experiences, provider competencies and system performance. A secondary analysis of databases was conducted to evaluate the utilisation of healthcare services and disease control for diabetes, hypertension and depression. Focus groups with patients suffering from these conditions explored the burden of treatment through qualitative methods in 10 sessions across PHC centres of public and social security subsystems. Additionally, 19 indepth interviews with healthcare providers and policymakers of public and social security subsystems examined programme activities, service characteristics and system interactions. A People’s Voice Survey, conducted via telephone with 1190 adults in Mendoza, captured users’ perceptions of the healthcare system. To assess diabetes care performance, an electronic cohort of 252 diabetic patients was followed through mobile phone surveys for 6 months. Lastly, a knowledge test embedded in a Ministry of Health training course evaluated healthcare providers’ competencies in managing NCDs, using questions based on provincial and national guidelines. Findings of all these components are being reported separately.30 31

The steering group initiated the process by convening a small, diverse panel of experts, including policymakers, healthcare professionals from various levels of care, directors of areas such as primary care and health promotion, quality improvement specialists, health centre directors, social workers and academic representatives. Through inperson meetings, this group reviewed the findings from all components described above and collaboratively developed a preliminary list of potential recommendations supported by evidence and aimed at addressing the issues identified in the studies (see online supplemental material). The operational framework for PHC guided this stage.32 These recommendations were designed to improve the provincial health system. Following this initial phase, the expert group was expanded to include a broader range of participants, who then engaged in the Delphi process to refine and prioritise the recommendations.

32 experts representing various levels and different roles of the Mendoza healthcare system were invited to participate in the consensus process to evaluate and choose a set of recommendations. The inclusion criteria required participants to have demonstrated public health expertise within the Mendoza province. Eligible experts included frontline PHC providers, NCD programme directors, area directors overseeing multiple healthcare centres, high-level decision-makers within the Ministry of Health (eg, secretariat officials) and academics affiliated with local universities. This composition ensured a wide range of perspectives, encompassing public and private sectors and various levels of care and health specialities.

27 participants completed the first two rounds, and 22 professionals accepted to participate in the final inperson round. Participants received no financial incentive and declared no conflicts of interest. The experts received an email link to an online questionnaire in each round. The questionnaire, hosted at zoho.com (Zoho, Pleasanton, California, USA), presented statements of potential interventions in PHC, implementation strategies for these interventions and approaches to adopt that could contribute to strengthening PHC with brief explanations and references. Experts had to evaluate each statement according to five criteria (potential impact, resource requirements, acceptability, feasibility and measurability) on a nine-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (no justification for the recommendation) to 9 (complete justification for the recommendation). The criteria (potential impact, resource requirements, acceptability, feasibility and measurability) were selected from the evidence to decision framework.33 34 Due to persistent challenges in interpreting the criterion of measurability, it was excluded from the evaluation in the final round.

Based on the expert scores, each recommendation received individual scores for each criterion, which were then weighted according to the importance assigned to each criterion. This resulted in the average total score for each statement or recommendation. In addition, the number of disagreements was calculated based on the extent to which experts agreed or disagreed when rating each criterion. The modified RAND/UCLA adequacy method was used to define consensus, considering the interpercentile rank and skewness. Then, based on these two values—a median of all criteria and the number of disagreements—recommendations were classified as appropriate (median score between 7 and 9 with no disagreement), uncertain (median score between 4 and 6 or any median score with disagreement) or inappropriate (median score between 1 and 3 with no disagreement).

The experts had 10 days to complete each round. In subsequent rounds, interventions and criteria that did not reach an agreement in the previous round were included for a new vote, and participants could view the anonymised scoring by other experts compared with their scoring.

The final round was inperson, held in Mendoza on 6 July 2023, and was led by two moderators. This meeting aimed to discuss the recommendations that showed disagreements in scoring the evaluation criteria and to reach a consensus whenever possible. 20 participants attended the meeting. The survey results were presented, and recommendations with disagreements were discussed and evaluated. Based on the consensus process and the final session, a document containing the recommendations was compiled and sent to the expert group for comments and suggestions.

The panel of experts for the Delphi consensus included a diverse group of stakeholders, such as members of academia, healthcare providers, decision-makers at various levels and healthcare professionals. Their expertise and insights shaped the recommendations developed through this process. Following the Delphi consensus, the results were presented to a broader audience, including patients, decision-makers and healthcare professionals, who participated in codesign workshops to collaboratively develop implementation strategies to improve PHC.

Of the 32 individuals invited, 27 (84.4%) agreed to participate. All 27 experts took part in the first two online rounds, and 22 (81.5%) attended the final inperson meeting. Table 1 shows participants’ characteristics.

Table 1

Participants’ characteristics

Experts evaluated 42 potential actions, including interventions and implementation strategies, aimed at improving PHC within Mendoza’s public health system. In the first round of evaluation, no recommendation received a high enough score (7–9 and no disagreements) to be categorised as ‘appropriate’. The recommendation to promote greater integration of provincial health subsystems received the lowest overall score. While panellists agreed on the very high impact (scores of 8 or 9) of 32 (76%) recommendations, these were considered to present challenges related to feasibility and resource requirements, as reflected in low scores or disagreements for these criteria. These included, for example, the implementation of the digital transformation bill, ensuring the availability of essential medicines and technologies in healthcare centres, introducing performance-based incentives for professionals and improving electronic medical records. The ‘Impact’ criterion consistently obtained the most agreement among panellists, whereas ‘Resources’ and ‘Feasibility’ saw fewer agreements. By the final round, 24 recommendations improved their overall scores to ≥7, and 13 of these also reduced disagreements, reflecting a stronger consensus among participants.

By the third round, the 19 (45.2%) recommendations that scored ≥7 in all criteria without disagreements were identified as ‘appropriate’. A total of 15 (35.7%) recommendations achieved ≥7 but maintained disagreements in their feasibility or the resources needed for their implementation.

The recommendations for improving the PHC system address key areas of healthcare delivery and system strengthening. In the policy and governance area, they emphasise continuity of effective interventions across government cycles, evidence-based policymaking and user participation in healthcare design. Quality improvement efforts focus on defining quality of care collaboratively, standardising evidence-based interventions and implementing incident reporting systems. Capacity building includes competency-based training and performance-based incentives. To strengthen system integration, participants propose optimising referral processes and promoting self-care. Resource management measures aim to improve appointment availability for patients with NCDs, ensure essential medicines and technologies and recover funds for the public sector of services provided to affiliates of other subsectors. In digital transformation, the recommendations call for implementing the Digital Transformation Act, leveraging information technologies for reporting and appointment management and enhancing electronic health records (box 1). The full list of possible interventions or strategies submitted to an evaluation, including those which did not reach the ‘appropriate’ category, is included as supplemental material.

Box 1

Recommendations with a score of ≥7 and no disagreements

As part of a collaborative cocreation effort, this process engaged local stakeholders across the health system, promoting a vision for redesigning PHC to meet the needs of patients and providers better. Over a 3-year evaluation in partnership with the Ministry of Health in Mendoza, our work identified limitations in patient experience, system efficiency and trust in the system. In response, local experts and stakeholders participated in a consensus process to develop a set of evidence-based recommendations aimed at improving quality, accessibility and patient-centred care at the primary level. This is the first initiative at the provincial level to provide decision-makers with contextualised information for health policy development. Key recommendations included process standardisation and optimisation, improved referral mechanisms, rigorous data recording practices, the promotion of patient self-care through education and the strategic use of digital technologies. These interventions address current deficiencies and offer a replicable model for strengthening PHC in other settings.

The expert panel’s recommendations align with effective intervention strategies identified in the literature for improving PHC, more specifically for managing NCDs. The strategic implementation of targeted interventions and evidence-based strategies has improved the quality and accessibility of services of PHC, ensuring more equitable health outcomes for diverse populations.35–40 For instance, the literature on patient engagement and its positive impact on health outcomes supports the emphasis on promoting patient self-care through education.35 41 The standardisation of care processes and the improvement of referral mechanisms are supported by findings that demonstrate that consistent protocols improve NCD management and that care coordination enhances continuity of care and patient satisfaction.38 41 42 Also, the integration of electronic health records, telehealth and continuous professional training has improved patient monitoring, communication and overall service quality.43–48 These evidence-based approaches validate the interventions proposed by our expert panel.

Recommended interventions to improve PHC originate from reviews which emphasise evidence-based approaches.35 36 44 49–51 Studies using Delphi methods focus on creating recommendations rather than detailing their implementation, highlighting a common gap in the literature.46 49 52–55 Notably, our recommendations are not only based on the international literature but are also underpinned by several local studies conducted in Mendoza.28 30 31 This locally produced evidence provides a robust, context-specific foundation that further validates and enhances the relevance of the proposed interventions.

A major strength of our initiative is the direct translation of expert recommendations into actionable policy. The integration of the Delphi consensus recommendations into the Health Plan was facilitated by the participation of the current minister of health and his team in the process. This involvement enabled a thorough understanding of the findings and ensured their timely consideration in strategic planning. The Health Plan is a broad initiative aimed at the structural transformation of the provincial health system, encompassing extensive reforms in management, financing and service delivery. Notably, the provincial legislature passed a package of 26 key laws to facilitate these necessary changes. This comprehensive reform seeks to optimise the efficiency and accessibility of the system while introducing new governance and management models founded on sustainability and equity. While challenges remain, including financial constraints, resistance to change and intersectoral coordination, the Health Plan represents an effort to improve efficiency, equity and sustainability in response to current population needs and future demands.25

The Delphi consensus method is not free from bias in participant selection and challenges in reaching consensus, which may affect the validity of recommendations. The temporal limitations of the cohort study that informed the process, especially the initial list of recommendations, may not have captured evolving patterns of care. This project included qualitative and quantitative components to enrich the depth of understanding of the health system and how the local population uses it. Including qualitative research adds richness that may provide valuable insights into nuanced aspects of the healthcare experience. Finally, the rigorous methodology and cultural sensitivity demonstrate a proactive approach to mitigating potential bias.

This collaborative effort has produced a comprehensive list of evidence-based recommendations to develop initiatives to strengthen the PHC services in the public health system in the province of Mendoza, Argentina. The recommendations address key areas such as governance, stakeholder and community engagement, resource allocation and service delivery. These recommendations are supported by locally produced evidence and international literature. This foundation reinforces the relevance of our findings. Importantly, the inclusion of our recommendations in the Provincial Health Plan highlights the practical impact of our work. Future studies or programme evaluations can test the effectiveness of this model, ensuring its validity and applicability to improve healthcare outcomes for the population of Mendoza.

Data are available upon reasonable request. Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This study involves human participants. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from an independent ethics committee, the Provincial Research Ethics Review Board: CoPEIS, on 3 May 2022. Approval number 61/2022. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

We thank all participants in this consensus process.