BMC Medical Education volume 25, Article number: 117 (2025) Cite this article

Medical educators play a crucial role in the perpetuation of the medical profession. Recent concerns have arisen regarding the quality and quantity of current teachers. To comprehend this shortage, it is key to understand future physicians’ attitudes towards venturing in education, their motivations and possible detracting factors. This study aims to explore graduating students' attitudes towards a future teaching role and identify motivating and hindering factors.

Sixty-eight students in their final year of medical training answered a digital questionnaire. Responses were processed using descriptive statistics and qualitative coding for the open-ended questions.

Teaching was the second most prevalent aspiring role (59%) after the clinical one. The most mentioned motivations were contribution to the future of medicine (50%), passion (31.8%) and sense of social duty (18%). Conversely, top hindering factors revealed non-economic disadvantages (85%), economic disadvantages (39.7%) and cost–benefit rationale (11.7%). Students’ recent experience across the undergraduate path provided insights about the influence of different agents, teachers’ exemplary attributes, and their own projection for their future role. Teaching is predominantly viewed as an honorable and aspirational role but constrained by inadequate economic compensation. Students feel confident on this path, with limited understanding of teacher professionalization.

Understanding students’ perspective in pursuing teaching careers offers insight that can address longstanding issues in the field. Strategic initiatives should focus on amplifying motivational factors, and addressing demotivational factors, like the lack of economic incentives, to strengthen the appeal of the teaching profession, and offer better resources to aspiring medical educators that may heighten their satisfaction and attract new aspiring professionals keeping high standards in their professionalization and performance.

Medical educators (ME) are key in the reproduction of the profession as they fuel the training of medical students, junior doctors and even throughout continuing professional development [1]. It is highly important to have talented, devoted, and well-prepared teachers. Even though the medical profession has had an inherent commitment to teaching, there is a claim that acknowledging medical expertise as a guarantee for teaching proficiency is not enough.

Untrained ME often face difficulties understanding how to convey the knowledge that they have learned, sometimes effortlessly and subconsciously [2]. This is reflected in medical education in Mexico, as 'teacher’s excellence' is the most deficient aspect of its structural elements [3]. The aforementioned can be explained partly by the low professionalization of medical education, as only 20% of teachers in the basic sciences area and 17% in the clinical area have pedagogical training [3]. Aside from this issue, there is increasing concern about ME shortage as detected on dropping applications [1, 4, 5]. In Mexico, only 69% of the medical schools have enough faculty which results on only 55% of the schools meeting the educational demand [3]. Our country’s difficulty is part of a larger global issue as also other low-and-middle-income countries face the same teaching staff shortage [6, 7]. This also puts pressure on the quality of available candidates. As less candidates are available and the shortage arises, proper evaluation of candidates may be hindered to fuel the necessary volume. These factors highlight the pressing need to recruit, retain, and prepare the next generation of ME [8].

In this context, understanding both motivators and demotivators is key. From the perspective of current teachers, the primary motivation for clinicians to engage in teaching is the desire to help educate the next generation of doctors [1]. Most of them enunciate intrinsic factors, in other words, driven by internal satisfaction like altruism, intellectual satisfaction and personal skills as their motivators [1, 9, 10]. Moreover, intrinsic types of motivation have been found to be more prevalent than those influenced by external (extrinsic) factors [11]. The challenge with motivations towards an educator profile is to differentiate whether they are aspirational or if they are recognized when individuals are already embodying the role.

Within the spectrum of medical trajectories, equally important to the motivators, is the analysis of what could make individuals avoid going through any of these paths. With regards to teaching, identified demotivators include clinical workload, lack of strong involvement in course design and lack of pleasure in teaching [1, 9]. Other frequent demotivators account for lower financial rewards and bureaucracy [11].

In an attempt to attract prospects, studies have focused on unveiling the benefits of developing teaching skills and trying to understand what could drive a medical doctor to a path in academia. Other initiatives involve programs that introduce, promote, integrate and prepare students, motivating them to become teachers in graduate and postgraduate contexts [5, 8, 12, 13].

Little has been explored about motivations of medical students to aspire to a teaching role in their future plans. When approaching career intentions in medical students, there is considerable fluctuation as they discover new interests and likings throughout, however extrinsic factors play a more prominent role than personal characteristics [11]. Understanding the interplay of variables such as gender, culture, country, and even immediate context like institution or medical school is key to assess motivating factors [5]. Also, generational differences must be weighed, as motivations and perceptions of the millennial student generation regarding their studies and future career plans have already defied educational policies and generation Z will probably twist the game again [15].

The purpose of this study is to explore the attitudes of medical graduates towards practicing a teaching role in the future and to identify factors that may either motivate or hinder such aspirations. Additionally, the study aims to explore their concept of an exemplary teacher and how their experiences throughout their education may influence their decision to consider such a career path.

Based on a literature review, we designed a hybrid survey to explore the graduates’ career plans and particularly their motivations to aspire to a teaching role (which can be found as a supplementary document). The instrument is an adaptation of a survey from Kiani et al. to the Mexican medical schools' context [16]. A pilot test was conducted with two individuals to ensure relevance and clarity for the target population. Also, their perception of the ideal teacher and the most important attributes were explored as well as their own sense of preparedness for the role. The survey was administered to graduating medical students from the School of Medicine and Health Sciences of Tecnologico de Monterrey in Mexico, currently engaged in their social service year program. This phase is a mandatory period per Mexican law to receive their grade and occurs upon graduation from a 6-year program. Interns practice academic, research and mostly clinical activities in urban and rural areas. This one-year phase marks an intermediate status where they've completed their academic path and are planning future steps in their careers.

The questionnaire had 16 multiple choice items and 6 open questions. The questions explored aspects in 5 categories: future plans, motivations and demotivators for a teaching career, teacher-role model, impact and experience of their teachers, and undergraduate teaching experience. The anonymous questionnaires were distributed digitally and self-administered online. A total of 68 subjects from three different campuses of the same medical school completed the survey, which represents 28.69% (N = 237) of the class. The sample comprised 44 (65%) women, 23 (34%) men and one person who identified as nonbinary. Responses underwent processing using descriptive statistics and qualitative coding for the open-ended questions. Potential correlations were explored in terms of campus and gender.

The revised first draft was processed using artificial intelligence to assess correct grammar, clarity, and writing style in accordance with standard scientific writing conventions. Further, the enhanced version underwent both authors’ revision and other two external revisors.

Respondents gave their informed consent for participation. Approval from an ethics committee was deemed unnecessary according to according to Mexican General Health Law on Research (considered without risk). The survey was anonymous, voluntary and respondents were invited through passive recruitment.

Regarding medical students' plans about their future, most students (84%) are clear on their next step after graduation. However, this tends to lower when students are asked about their plans in the following 5–10 years (67%) and their vision in the long run (76%). On the opposite end, 6% (4) of students are uncertain about their plans across the three-time frames.

When applying the gender variable, men are consistently clearer of their future plans than women. The least difference is noted in the immediate steps for postgraduate training, however in medium- and long-term plans, women score consistently lower (a differential of 18%) in projecting their career plan.

As expected in this profession, 99% of the students plan to continue their academic training. The vast majority (82%) opt for a clinical residency either in Mexico (63%) or in another country (19%). Only 10% are planning on pursuing research as an intermediate step. A minority are looking for a non-clinical degree (3%) and only 1 student is planning to start working as a general practitioner. The most notorious difference in terms of gender has to do with pursuing research after graduation, which occurs in 20% of men and only 2% of women.

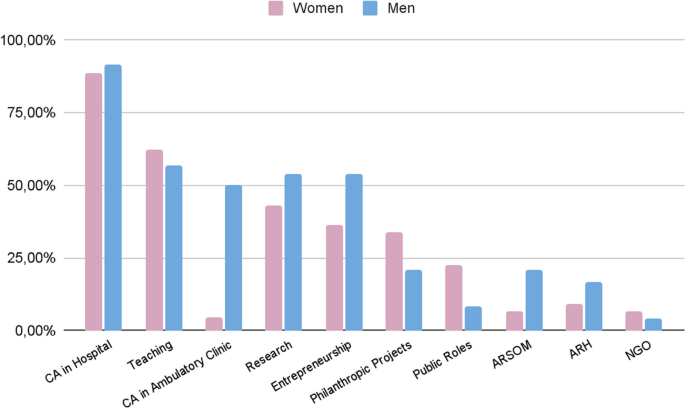

When asked about their future professional facets, most students choose 3 or more roles. The most prominent choice is clinical activity (CA) in a hospital environment (90%), followed by teaching (59%). Among the different roles and trajectories, the most popular options are also the most egalitarian in terms of gender; as shown in Fig. 1. Men are more prominent in their choice of entrepreneurship (54.1%), research (54.1%), administrative role in school of medicine (ARSOM) (20.8%) and administrative role in hospital (ARH) (16.6%). Meanwhile, women surpassed men in roles in public service (22.7%), philanthropic projects (20.8%) and non-governmental organizations (NGO) (6.8%).

The future doctors were queried about the motivating factors for taking on a teaching role. Most students prompted 1 or 2 reasons, a few gave 3 or more, and 5 students abstained from giving an answer. The themes that emerged in order of prevalence were along the following: contribute to the future of medicine (66%), self-centered motivations (48.5%), non-economic advantages (30%), sense of duty (13.2%) and economic advantages (3%). Table 1 displays the themes (with definitions) and subthemes along with illustrative quotes from the students' narratives.

Regarding gender, women provided more reasons (n = 1.6) compared to men (n = 1.2) behind their motivations for a teaching role. The most mentioned by them was contribution to the future of medicine (50%) followed by passion (31.8%) and social duty (18%). On the other side, men elicit passion as the main reason (50%), contribution as second (29.1%), and a faint 4% in social duty.

Meanwhile, when they were asked about demotivating factors to fulfill a role in teaching, consistent themes emerged (as shown in Table 2): non-economic disadvantages (85%), economic disadvantages (39.7%), cost–benefit rationale (11.7%), disadvantages related to teaching (7.3%) and self-centered demotivations (4.4%).

It's worth highlighting that “lack of appreciation/interest from the students” was the fourth most mentioned reason, just behind the time restraints, economic disadvantages and bureaucracy. Most of the mentions involve apathy and lack of interest of actual students in learning, however other specific attitudes were mentioned: “The attitude of the students…They are arrogant and very disrespectful to the teachers” and “little tolerance for frustration from the students”. This may show a concern emerging from interpersonal aspects, as they aspire for being respectfully treated, they might be able to sense or empathize with teachers that are not being fully respected or acknowledged. This aspect can also be weighed with the “generational gap” if that accounts for a distinct prioritization of values and professionalism.

To explore their concept about the ideal teacher, students were openly asked about the 3 main traits that a good teacher should have. Afterwards they were expected to choose the most important assets from 4 main domains: professional, teaching, interpersonal and personal domain from Kiani et al. [16].

With the open question, 57 different attributes emerged. The top 10 qualities represent 137 mentions (67%) and are listed in Table 3. Regarding gender, the same top 5 options were chosen; although patience was outnumbered by women, and men gave more importance to empathy and knowledge.

When processing the intuitive responses, the responders elicited traits under the 4 domains, the most prominent being under the interpersonal and personal scope. Results are presented in Table 4.

Students were asked to picture an exemplary teacher and then elicit the qualities to support their fine performance. The same attributes emerged, reflected in passion being the top choice. On the other hand, they were also asked to describe attributes of teachers who fell short in their performance, for which they consistently described opposing characteristics. However, when exposing characteristics of a bad teacher they tended to use traits under the teaching domain (uninterested, lacking teaching skills and intolerant to questions) followed by professional aspects (irresponsible).

When assessing the impact of different agents in their learning, students recognized ME that intervened during their medical courses to have the most impact (7.4/10), followed by ME in clinical clerkships (7.2/10) and finally basic science professors (6.8/10). Interestingly, they recognized their peers as having a similar impact as the formal educators (7.3/10). Residents scored 6.9 and teachers from non-medical courses scored 5.9, being the lowest.

Students were asked about how capable they feel of performing a teaching role. More than half of them (57%) expressed feeling very confident. The final question inquired how medical students have honed their teaching skills. Near-peer mentorship emerged as the most common (44%), followed by experiences in social service (30.8%), during clinical practice (13.2%), giving class presentations (11.7%), experiences not related to medicine (8.8%) and finally, in patient-care teaching experience (4.4%).

As medical students approach graduation, they are already envisioning their future careers. Even though the clinical role is prime, teaching is a very popular aspirational role. Teaching, along with other career plans, is mostly perceived as a complementary role linked to their clinical profile.

A couple of aspects that entail further exploration have to do with prestige and economic retribution associated with teaching in medicine, and the fact that it was only summoned as a secondary role (aside clinical practice). Medical students may be either consciously or intuitively aware of societal perceptions regarding the prestige of medical professionals [17]. Prestige tends to be valued by graduates of high reputation postgraduate programs, while those of lower status programs value salary more highly [18]. This has been studied in terms of choosing a clinical specialty against others [19, 20] but may be also translate to a low perceived status on the teaching role alone.

In 2023, college professors averaged earnings of $9,780.00 (Mexican peso)/month for almost 30 h of work per week [14]. This is equivalent to earning $18.11 dollars per day, being slightly above the daily minimum wage, which is $13.83 dollars per day, in Mexico [21]. On the other hand, medical doctors with a specialty earn more than 4 times this sum ($43,600 (Mexican peso)/month) [22]. It is worth noting that although both paths (teaching and clinical) may offer prestige or status, students tend to favor traditional medical practice due to its economic advantages [23]. In this case there is a tension between the aspiration of the teaching role which may provide status and prestige, conflicting with a low economic retribution. Beyond personal traits, an exploration of students’ social dominance orientation—defined as an individual’s preference for hierarchy and, therefore, prestige within a social system—may be crucial for a comprehensive understanding of how it shapes their motivation for further career decisions [24].

Examining the gender-based differences that emerge in career decisions can provide valuable insights into how social expectations and gender roles influence these choices. Men tend to have greater confidence in their short-, medium-, and long-term career paths and are more prone to choosing research, entrepreneurship and administrative roles which are still paired with higher prestige and earnings and may signal a more extrinsic drive in terms of motivation.

Meanwhile, women stand out in choosing roles in public service, philanthropic projects, and non-governmental organizations which in turn may be less regarded in terms of status and retribution and could relate to intrinsic motivations. The shaping of this professional profiles can be deeply rooted in gender socialization and access to opportunities and warrants further exploration.

Regarding the motivations for the teaching role, interest tends to be more democratized among genders. The thematic categories that encompass the reasons and motivations expressed by the students are hard to convey into an intrinsic vs extrinsic classification, however when focusing on demotivating factors, those lean towards more extrinsic aspects of the teaching role that come secondary or collateral to the actual role with regards to costs, efforts, and barriers that the students project.

Students’ perceptions and their idea of an exemplary teacher are important as they may relate to their own projections. Students highlight numerous desirable qualities, with the most valued often falling on the personal or interpersonal side. This contrasts with other studies that emphasize performance [25]. However, when judging bad teachers, they tend to point to the failures in the teaching domain. In other words, medical students demand respect and good treatment from the already competent and proficient ME. Their explicit demand for respect was surprising and may relate to a normalized culture of mistreatment in medical education that is being summoned [26]. It is estimated that between 40 to 60% of medical students have experienced some form of mistreatment, some ME may think that this “ritual of humiliation” was effective in making them learn, which can perpetuate this vicious cycle [27, 28].

When judging the impact of different agents in their learning, the fact that students considered their peers to be almost equally significant than their ME is something worth scrutinizing. Explanations can be sought by reflecting to what extent it can mean a low performance from their ME, or a highly appreciated lateral apprenticeship. This could be related to continuous engagement in immersive learning opportunities that go beyond formal teaching interactions and may happen often with peers.

The fact that most students feel confident in their teaching skills resonates with their recognition of informal opportunities for development, such as tutoring, study sessions, and taking charge of delivering classes or presentations throughout their academic journey. Another possible explanation is that they interiorized the myth of the 'bright person', which assumes that being expert in a field is enough to teach what they know to someone else. However, these perceptions can fall short on the real underpinnings of the teaching competencies expected in the professional realm, particularly if their models are not providing a high enough standard in teaching performance. Further investigation can be conducted by assessing skills and correlating them with reported informal experiences and perceptions.

The fact that no agent scored higher than 7.4/10 in their perception of impact in learning may also signal the extent on which this career relies on self-learning, which could be addressed in another opportunity.

Limitations to this study include a low response rate. We believe that the low response rate from students was due to the survey being administered and answered on a voluntary basis. This arises a possible bias concerning voluntary participation from students that are more prone to abide by academic motivations.

As information in the medical sciences becomes increasingly vast, it is evident that medical education encompasses much more than the mere transmission of data. The skills required to prepare future doctors may challenge the paradigm through which traditional educators were trained, given the evolving landscape of technology, knowledge, and professional values. Within this highly competitive career, expertise in the field is essential, but the ability to impart knowledge and cultivate competencies in students is imperative.

To address the demand for an adequate quantity and quality of ME, incentives must be carefully considered to attract well-suited candidates for the role. Strategic initiatives should focus on amplifying both motivational factors, such as passion, and addressing demotivational factors, like economic incentives, to strengthen the appeal of the teaching profession. Also, the factors that hinder women to pursue the same paths as men. As they are not being addressed, they negatively impact social expectations while also reinforcing gender disparities in the ongoing struggle between women's career aspirations and the available opportunities.

The hidden curriculum, which represents the culturally acquired and unintended lessons that students internalize, often diminishes the status of ME who are distant from the clinical role [29]. The paradigm of teaching as a complimentary role can work better if professionals are mindful and responsible about teaching as a matching career. This entails being a ME while also being an expert in a particular domain, rather than being solely an expert clinician who teaches.

To regard teaching as a highly honorable and prestigious profession, would require recognizing the transcendence and impact, pairing it up with the typically asserted recognition that clinicians have for “saving lives” and aligning it with proper retribution. Failure in aligning these aspects poses the risk of losing talent to other more rewarding paths.

There is yet to determine if the path of professionalization in the teaching domain is worth instilling during postgraduate education, or even acknowledging it from the undergraduate level. After all, at least in the vast clinical training for this profession, students and residents rely on fellow colleagues for learning as well. It would be interesting to reflect on the best approach, if only deriving students who are explicitly interested in the path or to sprinkle some of these premises in the general curriculum.

Another less explored avenue is to heighten other possible applications of pedagogical training, aside from the labor needed to train future doctors. Exploration is needed to determine whether these skills could enhance performance with patients, especially in times when education for autonomous decision-making is crucial, as well as in other settings where physicians can make an impact.

Given the traditional role of physicians in fostering the development of the next generation of medical professionals, it is imperative to recognize that evolving times demand clear delineation of skills in this field. This, in turn, may involve contributing to academic medicine beyond the transmission or facilitation of the learning process in a classroom or clinical setting.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the “RESULTS” repository, as a supplemental material. We also provide the survey in the supplementary information files. We do authorize the survey for its publication and/or use.

- NGOs:

-

Non-governmental organizations

- CA:

-

Clinical activity

- ARSOM:

-

Administrative role in school of medicine

- ARH:

-

Administrative role in hospital

- ME:

-

Medical educators

We would like to thank graduating students that volunteered and generously shared their perspectives. Also Dr. Adelaida Caicedo Fajardo and Dr. Xiomara Hinojosa for their review and recommendations on the final version of the manuscript.

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of Writing Lab, Institute for the Future of Education, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico, in the production of this work.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval from an ethics committee was deemed unnecessary according to according to Mexican General Health Law on Research (considered without risk). The survey was anonymous, voluntary and respondents were invited through passive recruitment. Respondents gave their written informed consent for participation.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

González-Amarante, P., Romero-Padrón, M.A. Motivations for a career in teaching: medical students’ projections towards their future role. BMC Med Educ 25, 117 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06536-2