Long-Awaited Puberty Blockers Study Is Out In Pre-Print, Finding No Change In Kids' Mental Health

A much-anticipated study on the use of puberty blockers among a group of nearly 100 minors with gender dysphoria has finally emerged in pre-print form. The study found that, contrary to what Dutch researchers who founded the field of pediatric gender medicine in the 1990s and 2000s found in their seminal 2011 paper, children’s mental health markers did not improve while on the drugs. Instead, the children had fairly good mental health overall that simply remained constant during the year or two they spent on blockers.

In October, New York Times reporter Azeen Ghorayshi reported that the study’s lead author, Dr. Johanna Olson-Kennedy, had long withheld the study, which finished gathering its data in 2021, from publication for political reasons. She did not want its null findings, which she found unexceptional, to be weaponized. This came after British researchers had also tried and failed to replicate the Dutch study’s finding that blockers improved mental health. Having explicitly hypothesized that blockers would improve mental health, the British researchers also sat on their null findings for years and finally published them in 2021.

Dr. Olson-Kennedy, who is perhaps the nation’s leading pediatric gender care doctor and heads a gender clinic at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, asserted in a sworn court statement in November that the Times mischaracterized her words.

Yesterday, the Times dropped its own long-awaited assessment of pediatric gender medicine: a six-part podcast series called The Protocol, led by Ms. Ghorayshi. I highly recommend everyone listen to the full series, which examines how the treatment for pediatric gender dysphoria pioneered by the Dutch—prescribing puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to minors with persistent, insistent and consistent gender dysphoria—found its way to the United States. There, clinicians abandoned many of the protocol’s guardrails in favor of the so-called gender affirmative method. Under this philosophy, the child’s wants, needs and self perception were now considered paramount. I wrote a summary of the Times podcast in this X thread if you want to check it out.

The podcast establishes as foils two leading women in the nation’s pediatric gender care field: Laura Edwards-Leeper, who as a young psychologist first imported the Dutch protocol to the U.S., to Boston Children’s Hospital, in 2007; and Dr. Olson-Kennedy. Dr. Edwards-Leeper recalls a panel she sat on at a conference in 2015 in which she found herself squaring off against Dr. Olson-Kennedy. Dr. Edwards-Leeper supported a more cautious and circumspect approach to assessing gender dysphoric children to determine whether they were good candidates for puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. Dr. Olson-Kennedy disparaged such assessments as unnecessary and even harmful.

Dr. Olson-Kennedy got a standing ovation from the conference crowd. Dr. Edwards-Leeper knew this was a turning point for her and for the field at large. Knowing that her perspective was falling out of favor, she became increasingly concerned that what she saw as heedless and reckless care of children with gender dysphoria would only lead to a backlash that would harm the entire field. And indeed, there has been such a backlash, with Republicans leveraging the stories of detransitioners asserting they received shoddy care in their effort to ban such treatment altogether.

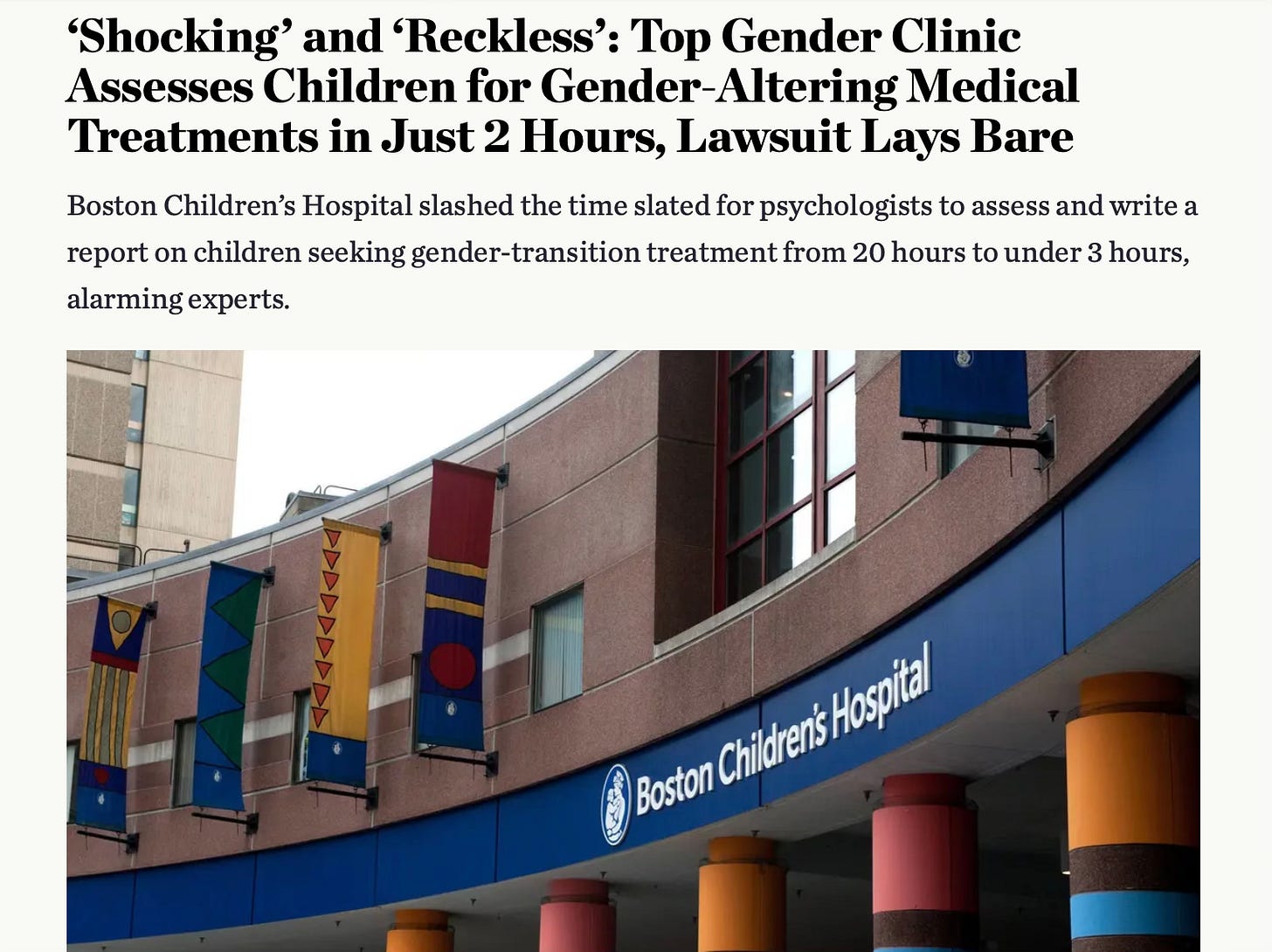

In October, I broke the news that since 2018, Boston Children’s held a policy that children seeking blockers or hormones would receive only a single two-hour assessment appointment with a psychologist before the clinic would decide whether to refer the child to endocrinology. Dr. Edwards-Leeper, who left Boston Children’s in 2011, told me this policy was “shocking.” Her former colleague at Boston Children’s, psychologist Amy Tishelman, called the policy “reckless.”

It is telling that Boston Children’s kept this policy secret for nearly seven years. The information only came out because of testimony in a lawsuit that Dr. Tishelman waged against the hospital, accusing them of gender-based discrimination and retaliation (she won on the latter claim, but the hospital is appealing).

If you want to hear Boston Children’s Hospital staffers defending their assessment policy, check out this podcast:

In December, Dr. Olson-Kennedy was sued by a young woman to whom the doctor prescribed puberty blockers on the first appointment when she was 12 years old, despite the fact that the child did not meet the criteria for a gender dysphoria diagnosis, having had gender-related distress for less than six months at the time. Dr. Olson-Kennedy then put the child on testosterone at 13 and encouraged her to have, and signed off on, a mastectomy when the child was 14, even as her mental health deteriorated. By the time Dr. Olson-Kennedy encouraged the child to have a hysterectomy at 17, the child’s ambivalence had taken hold and she ultimately detransitioned.

Earlier in the year, I began publishing a 12-part series of training videos that I obtained in which Dr. Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues schooled mental health professionals about the gender-affirming care method. The videos are a fascinating window into how Dr. Olson-Kennedy approaches caring for children who are distressed about their gender and who seek to transition. She makes clear that she has poor regard for the DSM-5’s criteria for diagnosing gender dysphoria. And she and her colleagues call into question whether a child should have to harbor distress about their gender to qualify for blockers and hormones.

I’ve published five hours of the training vidoes so far. Here are the two in which Dr. Olson-Kennedy herself is the speaker:

Subscribe to get these videos as I publish them:

Dr. Olson-Kennedy is perhaps most known for saying during a different training of mental health providers that was caught on tape:

“What we do know is that adolescents actually have the capacity to make a reasoned, logical decision. And here’s the other thing about chest surgery: If you want breasts at a later point in your life, you can go and get them.”

As for Dr. Olson-Kennedy’s assertion that the Times mischaracterized what she said regarding why her puberty blocker study had not yet been published, here is the transcript from the tape included in the podcast:

Azeen asked her why she hadn’t yet published the results.

To be quite frank, your manuscripts have to be so air-tight, there’s not even room for postulation anymore, right?

Because of the political environment?

Yes, yes.

She said it had to do with politics.

I mean, are you worried that people will say there was no change, therefore this didn't replicate the Dutch and it gets used against you or against the care?

No, I think what is more. And I want to reframe, like, it’s not necessarily worry, it’s just care. It’s care and concern about this information being interpreted to fit a narrative that isn’t real. And so, what concerns me is that that people get their information on formerly called Twitter, and it’s one sentence that says “Intervention after two years, doesn’t change outcomes.” And then it’s using court against where we shouldn’t use blockers because it doesn't impact them. It takes more than one sentence to talk about, well what does that mean? I do not want our work to be weaponized. It has to be exactly on point, clear and concise. And that takes time.

The puberty blocker study is but one product of a National Institutes of Health grant that Dr. Olson-Kennedy won in 2015 that has since contributed about $10 million to various studies of the care of youth with gender dysphoria. The blockers study was released quietly in pre-print form on May 16. A representative from Children’s Hospital Los Angeles sent it to me yesterday and told me that the authors are seeking to have it published in journal.

The study, as it notes, involves the “largest longitudinal cohort of youth with gender dysphoria initiating medical intervention with puberty blockers in early puberty to be followed in the United States.”

Oddly, in the “What this study adds” section, the pre-print asserts: “Youth demonstrated both stability and improvement in emotional and mental health over 24 months.” This is directly contradicted by the pre-print’s abstract, which finds: “Depression symptoms, emotional health and CBCL [the Child Behavior Checklist, which is an assessment survey filled out by a parent or guardian] constructs did not change significantly over 24 months.” It is possible that the first quote is alluding to suicidality, which did seem to improve over time.

The study authors concluded: “Participants initiating medical interventions for gender dysphoria with GnRHas [puberty blockers] have self- and parent-reported psychological and emotional health comparable with the population of adolescents at large, which remains relatively stable over 24 months. Given that the mental health of youth with gender dysphoria who are older is often poor, it is likely that puberty blockers prevent the deterioration of mental health.”

During earlier years of the pediatric gender care movement, puberty blockers were often held up by leaders in this field as a discrete intervention that provided its own mental health benefits, given this is what the Dutch researchers found with their initial cohort in their 2011 paper. Investigators at Britain’s pediatric gender clinic sought to replicate these findings but, in an analysis of their data first released in 2023, found that about 1/3 of the children on blockers saw their mental health improve, 1/3 got worse, and 1/3 stayed the same.

By last year, leaders in this field, including Dr. Olson-Kennedy, began to argue that it was wrong for others to conceive of puberty blockers as separate from cross-sex hormones. The two treatments were part of an inextricable treatment continuum, they argued in an amicus brief submitted to the Supreme Court in the case over the constitutionality of Tennessee’s ban on pediatric gender-transition treatment. Therefore, they said, it was faulty of Britain’s Cass Review of this medical field, which found the field was based on “remarkably weak evidence,” to assess puberty blockers as a discrete intervention and to place outsize expectations on the outcomes related to those drugs.

Pediatric gender medicine leaders, acknowledging that almost all children who start blockers for gender dysphoria continue onto cross-sex hormones, have moved away from arguing that blockers provide a “time to think.” Instead, in Dr. Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues’ new pre-print, they assert that “puberty blockers are often used either as a temporizing measure to bring one’s gender identity into focus or as the initial stage in phenotypic gender transition.”

The basic idea is that because blockers only stop unwanted physical changes and the emergence of secondary sex characteristics, they should not be expected to actually improve the mental health of adolescents with gender dysphoria. Instead, it is the cross-sex hormones that should provide such benefits, by bringing the child’s body more in line with their gender identity through the development of cross-sex secondary characteristics.

The pre-print, nevertheless, cites various studies that found that blockers “are associated with decreased suicidal ideation, behavioral and emotional problems, depressive symptoms and with better general functioning.”

The paper also downplays how many children taking blockers continue onto hormones, saying that “most but not all” do. In general, more than 90% do so, studies have found.

The puberty blocker study’s 95 participants were enrolled between July 2016 and June 2019 as a part of the NIH-funded Trans Youth Care United States Study. One participant did not start blockers, leaving the study with 94 children in its analysis. Given the youth were followed for a maximum of 24 months, Dr. Olson-Kennedy and her colleagues therefore took four years to analyze and finally publish their data.

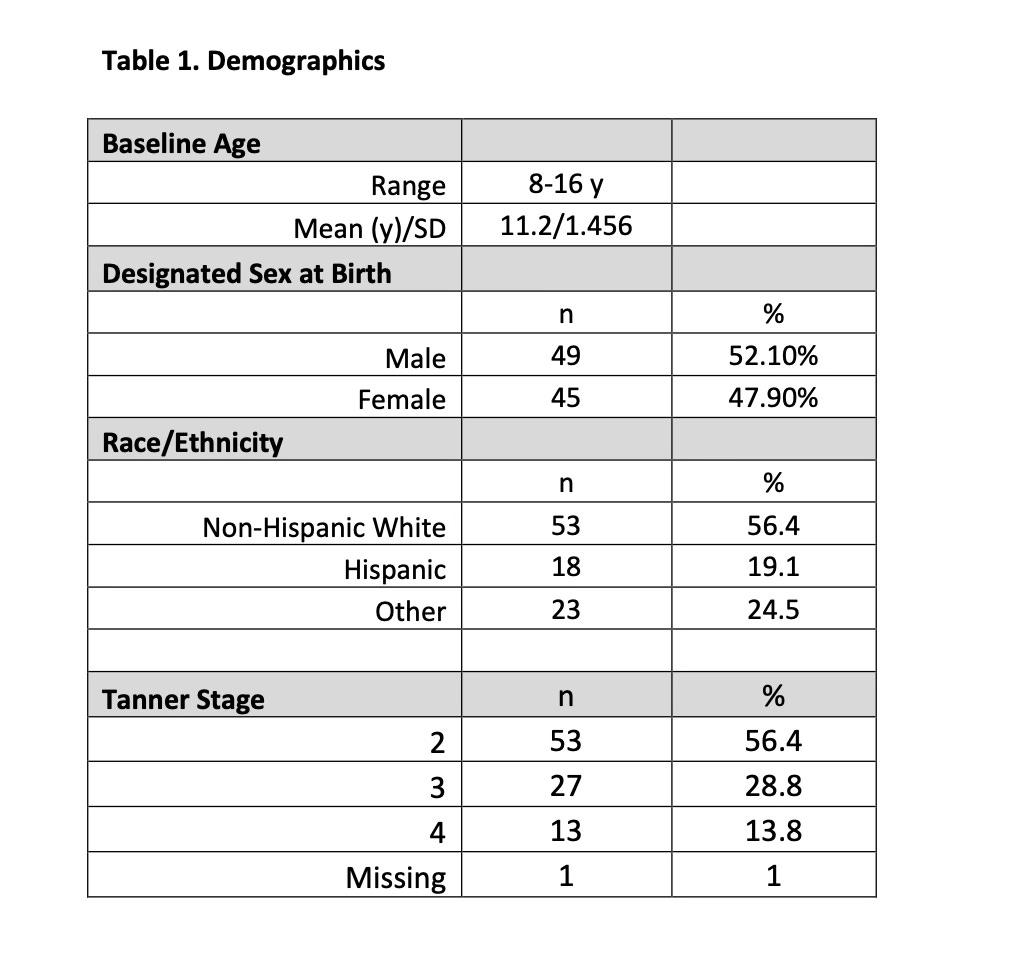

The children ranged from eight to 16 years old, with an average age of 11.2 years when they started blockers. The standard deviation for age was 1.46 years, meaning that the bulk of the kids were between 9.75 and 12.7 years old upon starting the drugs. Fifty-six percent of the participants were non-Hispanic whites and 52% were natal males. Fifty-six percent started blockers at Tanner 2, 29% did so at Tanner 3, and 14% did so at Tanner 4.

These days, the majority of children presenting at gender clinics, including Dr. Olson-Kennedy, are natal girls. So the fact that a slim majority of this puberty blocker study were natal males suggests that the cohort might not be quite as representative of the current crop of kids presenting with gender dysphoria and seeking blockers. Dr. Olson-Kennedy said in one of the training videos I published that kids typically come into her clinic when they are in their mid-teens have already progressed into puberty.

As for the kids in the puberty blocker study, 85% were in the so-called Tanner 2 or 3 stages of puberty when they started blockers. (Tanner 2 is puberty’s initial onset; Tanner 5 is completed puberty.) Twelve percent of the children started cross-sex hormones within the first 12 months of blocker treatment and another 21% began hormones between the 12- and 24-month mark. Among the 32% who started hormones, they did so after an average of 1.2 years on blockers.

As Dr. Olson-Kennedy told the Times, these children’s mental health was good overall. An assessment of their depression found that 72% had an average score at the study’s outset, and that 10% had mildly elevated depression, 10% had moderately elevated, and 8% had severely elevated depression. These figures remained essentially unchanged across the 24-month assessment period, during which children responded to surveys at the baseline point and at the 6-, 12-, 18- and 24-month points (provided they had not yet transitioned to cross-sex hormones).

Other markers of mental health also remained essentially constant.

One mental health marker that did appear to improve was suicidality, although it’s unclear whether the study authors considered this shift statistically significant. At the study’s baseline, 20 of the children reported ever experiencing suicidal ideation, 11 had done so during the prior six months, three had made a suicide plan in the past six months, and two had reported a suicide attempt during the previous six months, one of which led to an injury requiring medical care. At the 24-month mark, five participants reported suicidal ideation during the previous six months, none had made a recent suicide plan and one had attempted suicide recently, but this did not result in an injury requiring medical care.

In the study’s discussion section, Dr. Olson-Kennedy and her coauthors misrepresent the British puberty blockers study in particular when they assert: “Prior findings suggest that youth with gender dysphoria who have access to puberty blockers either demonstrate improved mental health or experience neutral effects, potentially preventing worsening mental health related in part to gender dysphoria.” As I mentioned, 1/3 of the British children actually got worse while on blockers.

Dr. Olson-Kennedy and her coauthors continue: “The results presented here are consistent with the prior literature and demonstrate that the mental health of youth as reported by both themselves and their parents/guardians is relatively stable from baseline over 24 months after starting medical intervention with GnRHa [puberty blockers].”

Although they used different metrics to assess mental health markers in the youth, the study authors assert that the participants’ mental health is comparable to the general population of youth as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavioral Survey from 2021.

“Among our participants at baseline lifetime suicidal ideation, plan and attempts were comparable to those of the general population, and after 24-months following initiation of medical intervention with GnRHa, were lower than the national average,” the study authors write.

Among the limitations of the study noted in the pre-print were the fact that not all of the participants stayed on blockers for 24 months, limiting the authors’ ability to analyze this treatment separate from hormones. And the children typically had at least “some level of parental support.” Such support is associated with better mental health in children with gender dysphoria. So the study authors postulated that their findings might not be generalizable to other children with different family dynamics.

There is no mention of the lack of a control group as a limitation. This is a major criticism that the Cass Review in Britain levied against studies in this medical field and a reason why their findings a typically unreliable, per multiple systematic literature reviews.

The sample size in the puberty blocker study was also small, limiting the ability of the researchers to detect statistically significant shifts in mental health among the children, and in particular among subgroups, such as those who started blockers in one Tanner stage versus another.

The study also relied entirely on self report and the report of parents—another problem that bedevils this field. It is notable that many advocates of pediatric gender medicine have reacted with fury to the assertion by people such as Dr. Hilary Cass, the author of the Cass Review, or Dr. Riittakerttu Kaltiala, chief psychiatrist at the Tampere University Hospital Department of Adolescent Psychiatry in Finland, that researchers should examine objective measures of those who have received gender-transition drugs, such as whether a young person leaves the house, attends school, has a job or has a romantic partner.

In the Times podcast, Dr. Marci Bowers, a gender-affirming surgeon and the former president of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, or WPATH, expressed her own disgust at Dr. Cass for seeking such proof that transgender people are objectively functioning better after transitioning. As Dr. Bowers did when I spoke with her last year, she characterized gender-transitioning, including the surgeries she provides, as a panacea.

the Washington Post, The Atlantic and The Nation. Follow me on Twitter: @benryanwriter. Visit my website: benryan.net.