BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 25, Article number: 161 (2025) Cite this article

Hospitalizations are a resource-intensive form of healthcare use, particularly for persons with chronic conditions such as HIV. In standardized Canadian hospitalization databases, it can be unclear whether a hospitalization record is an independent hospitalization, a planned interhospital transfer, or an unplanned readmission. Misclassifying hospitalization records can bias metrics (e.g., counting transfers as readmissions can inflate readmission counts) and hence yield incorrect results. We compared definitions for combining sequential, related hospitalization records to create hospitalization episodes of care (HEoC) within a cohort of persons with and without HIV (PWH; PWoH) in British Columbia (BC), Canada.

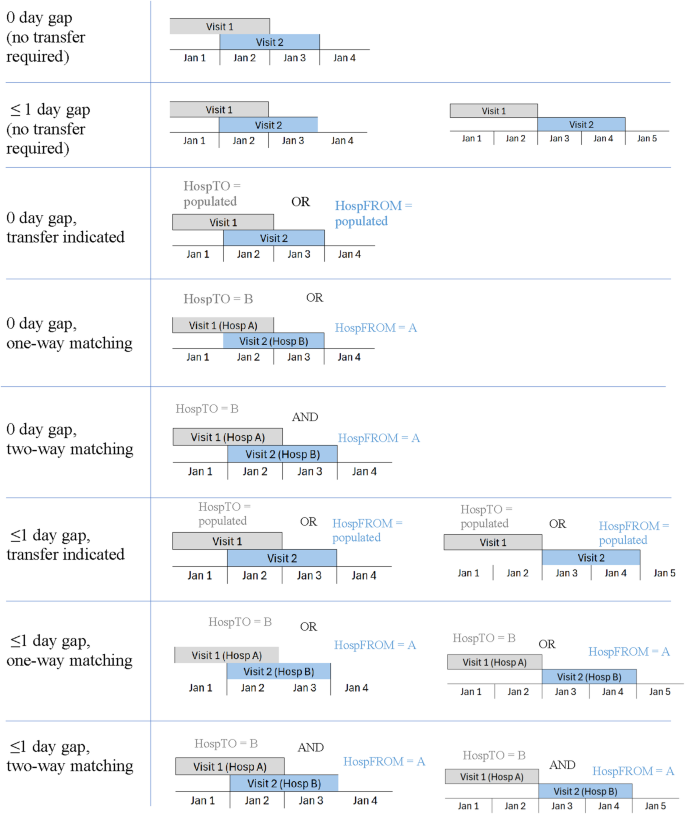

Acute care hospitalization records (April 1992 to March 2020) were sourced from the Discharge Abstract Database within the Comparative Outcomes And Service Utilization Trends (COAST) study, a BC data linkage that includes samples of PWH and PWoH. Guided by published approaches and data quality considerations, we compared eight HEoC definitions applied to PWH and PWoH. Definitions varied by the date gap between records (0 day [same-day] or ≤ 1 day), and transfer indication (none required, populated transfer fields, one-way matching of hospital transfer identifiers, or two-way matching of hospital transfer identifiers). Comparisons were primarily informed by the percentage of multi-record HEoCs (HEoCs involving multiple hospitalization records, including interhospital transfers), and feasibility given data quality.

The sample included 56,455 hospitalization records from 10,826 PWH, and 973,430 hospitalization records from 299,053 PWoH. Across the eight HEoC definitions, the percentage of multi-record HEoCs varied from 2.8 to 6.0% among PWH and 3.6 to 5.5% among PWoH. Definitions yielding the highest percentage of multi-record HEoCs combined records without requiring a transfer indication; definitions yielding the lowest percentage of multi-record HEoCs required two-way agreement of hospital identifiers. Patterns were generally comparable among PWH and PWoH, and similar in sensitivity analyses.

Various approaches can be used to define HEoCs. We recommended a balanced HEoC definition – requiring at least one populated hospital identifier field (without requiring matching of hospital identifiers) and ≤ 1 day gap between each hospitalization record for general use purposes in HIV research. Future work may examine these definitions in other settings and populations.

Measuring hospital-based healthcare use is necessary for research, evaluation, and quality improvement efforts. In many regions, hospitalization is the most resource-intensive form of healthcare use [1, 2]. Over C$59 billion was spent in Canada on hospital-related care in the 2021/22 fiscal year [3]. Hospitalizations are particularly relevant in HIV research, as people with HIV (PWH) tend to exhibit higher healthcare utilization, hospitalization, and readmission rates than people without HIV [4,5,6].

Hospitalization metrics such as the length of stay (LoS) can help guide appropriate resource allocation for particular conditions; longer LoS often leads to increased healthcare system costs [7]. Another key metric is readmission rate, which represents a common outcome in research and an indicator of health system performance, with a lower rate generally denoting better care management [8, 9]. Understanding how these and other hospital-related measures have evolved for PWH is particularly important, as life expectancy and quality of life for this population have markedly improved in recent decades due to effective antiretroviral therapies [10, 11]. Examining such hospitalization-related patterns, however, requires a germane understanding of hospitalization records.

Typically, inpatients receive care in a single hospital and then are discharged back to the community [12]. Some inpatients, however, require interhospital transfers for specialized care, clinical interventions, and other needs [12]. Other inpatients may be discharged, then experience an unplanned hospital readmission (typically within a few days or weeks). Misclassifying hospitalization records can bias research findings, particularly LoS estimates and readmissions. Treating transfer-related hospitalizations as independent hospitalizations, rather than components within the overall hospitalized stay, can underestimate LoS by failing to capture the totality of a person’s time in hospital. Additionally, treating transfer-related hospitalization records (constituting planned interhospital transfers) as unplanned readmissions can inflate readmission estimates [12]. Thus, caution must be taken to avoid misclassifying hospitalization records in an analysis. As is often the case for routinely collected administrative health data, some transformation of the data is required to render the data more useful for research [13]. To this end, when using hospitalization records for research, it is often more appropriate to combine transfer-related hospitalization records into hospitalization episodes of care (HEoC) rather than use the records in their raw form (see Supplemental Information Fig. 1 for a visualization of the HEoC concept). HEoCs can be single-record (a single, independent hospitalization) or multi-record (a sequence of multiple, related hospitalizations). Therefore, using the HEoC methodology can help reduce bias in estimates of key hospitalization measures in epidemiologic research generally, as well as for research focused on populations with high levels of healthcare use, such as those living with HIV.

No single standardized definition exists for combining hospitalization records to identify HEoCs [14], but a handful of Canadian publications have described criteria to do so. Although the present study focuses on hospitalization data in Canada (the Discharge Abstract Database [DAD]), this data structure has similarities with hospitalization data in several countries including the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States [15,16,17]. We examined prior Canadian methodologies to define HEoCs, and summarized five publications (see Supplemental Table 1), particularly regarding two key criteria for defining HEoCs: (a) the temporal gap between hospitalization records (from a discharge to next admission), and (b) if/how a planned interhospital transfer was identified. Three publications [18,19,20] permitted a ≤ 1 day gap between hospitalizations (i.e., a discharge date on the same day as a subsequent admission [a ‘0 day’ gap; e.g., Jan 1: discharge, Jan 1: subsequent admission], or a subsequent admission date the day after a discharge date [a ‘1 day’ gap; e.g., Jan 1: discharge, Jan 2: subsequent admission]); the other two publications [12, 21] used a 0-day gap. All but one publication [18] required some indication of a planned transfer as a necessary criterion to combine records into an HEoC. For definitions requiring evidence of a transfer, only one indication (from either the receiving or sending facility) was required [19,20,21]. Hence, it appears that most Canadian HEoC identification approaches deem only transfer-related hospitalization records eligible to be combined together into HEoCs (rather than additionally combining readmissions).

Although useful, the five HEoC definition publications were tailored to particular contexts or relied on specific data being available. For example, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and Rosella et al. publications [19, 21] provided no comparisons of different HEoC definitions, as their aim was not to contrast different options. In fact, the CIHI document presented no results regarding validity metrics, as it was a descriptive methodological document rather than research. Given the focus of Fransoo et al. [20] on intensive care unit (ICU)-related hospitalizations, they noted that their patterns may not apply to hospitalizations more generally, since only approximately 10% of recent hospitalizations in Canada involved the ICU [22]. Three publications included recommendations based on hourly admission/discharge times [12, 19, 21], which is inapplicable when only dates are available in one’s research extract. Peng et al. [12] also did not consider transfer status in their comparisons, as their study focused entirely on temporal gaps between hospitalizations. Similarly, Osman et al. [18] did not require indication of transfer, an omission which may bias some metrics as it would include readmissions as HEoC components. Additionally, HEoC definitions were typically based on general population samples; none were implemented/examined among PWH, which is significant given that this group exhibits healthcare patterns distinct from the general population. For example, hospitalization readmissions are higher among PWH, and relatedly, occurrence of self-discharge from hospital is more frequent [23, 24]; both these factors are examples of hospitalization use patterns that may impact identification of HEoCs among PWH. There is thus a need to re-examine, compare, and consider additional definitions to identify HEoCs using various criteria (including criteria that permit flexibility in available data), and examine how definitions function for PWH.

Building on published methods, we identified HEoCs using standard Canadian hospitalization data and compared how definitions functioned when applied to two samples: PWH and persons without HIV (PWoH) in British Columbia (BC), Canada. Understanding how HEoC definitions function among PWH and PWoH can help inform hospitalization-related metrics in HIV research, especially for research comparing people with and without HIV [25,26,27]. The aims of this work were therefore specific to providing an examination and comparison of HEoC definition options for HIV research (including comparative research with PWoH), and also to demonstrate how such definitions function among PWoH, which is essentially a general population cohort.

We focused on pragmatic approaches for identifying an appropriate date-based gap (given hourly information may be unavailable in versions of the DAD that researchers use for analyses) and the nature of transfer indication required (anticipating non-perfect data quality of transfer-related fields). We expected that definitions requiring no transfer indication would on average result in the highest percentage of HEoCs containing multiple records, and longest LoS. Relatedly, we anticipated that definitions requiring stricter criteria (i.e., two-way agreement of hospital identifiers) to – on average – yield the smallest percentage of HEoCs containing multiple records, and thus shortest LoS. Note that PWH overall tend to have more complex healthcare needs and comorbidities than PWoH [10, 28, 29], and thus one could expect PWH to generally have a longer LoS; however, our study focused on methodology rather than on addressing substantive questions about differences in hospital-based metrics for PWH vs. PWoH.

Hospitalization records were sourced from CIHI’s DAD database [30], within the Comparative Outcomes And Service Utilization Trends (COAST) study based in BC, Canada [25]. BC had approximately 5 million residents as of the 2021 Census [31], and a first-dollar universal healthcare system whereby costs for necessary medical care for residents are paid by the province [32]. COAST is a population-based linkage of clinical, demographic, healthcare use, and mortality records of adults aged ≥ 19 years, which includes a cohort of PWH who were identified via having a detectable plasma viral load for HIV, a dispensed antiretroviral medication for HIV [33], an HIV/AIDS related death, and/or meeting the criteria of an HIV case-finding algorithm applied to healthcare records [25, 34]. The first two indications were sourced from the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS’s Drug Treatment Program, a program that provides medications at no direct cost to enrolees in BC; the latter two indications were based on administrative healthcare data. The validated HIV case-finding algorithm exhibited high specificity against a reference standard of lab-confirmed HIV status in BC [34]. In addition, COAST includes a 10% random sample of the general population in BC with known PWH removed (i.e., a PWoH cohort, for comparison); further detail on this linkage has been previously described [25].

Individuals were assigned unique IDs applicable linkage-wide. The administrative datasets were provisioned by Population Data BC, a data provider in BC, and approved by Data Stewards that are responsible for reviewing data linkage and use for a particular research request [35]. Access to data provided by the Data Stewards is subject to approval, but can be requested for research projects through the Data Stewards or their designated service providers. The Consolidation File and DAD datasets, which are held by Population Data BC, were used in this study. One can find further information regarding these data by visiting the Population Data BC project site: https://my.popdata.bc.ca/project_listings/18-223/. The Consolidation File provides basic demographic information for individuals including sex, birth year, and time-varying geographic residence. The DAD contains data on hospitalizations from all BC-based acute care hospitals, including day surgeries (e.g. surgical procedures requiring acute care facilities). All Canadian regions (except Quebec) submit hospitalization records to CIHI, which compiles and standardizes records into the DAD [30]. These records are generated within a largely standardized system, with some level of quality assurance: hospital abstractors require dedicated training, and detailed data entry manuals/protocols exist [36, 37]. When an interhospital transfer occurs in the DAD, a separate hospitalization record is created [12]. Aligned with prior work, we subset to acute care hospitalizations [12], and included records from BC residents with admission and discharge dates contained within April 1, 1992 to March 31, 2020. For privacy reasons, hospitalizations involving abortions were excluded from the COAST linkage (standard practice by the data provider, Population Data BC).

To combine related hospitalization records into HEoCs, two sets of fields were considered: (a) dates, and a (b) hospital transfer flag. Dates included dates of admission and discharge. Although time is recorded in the hospitalization database generally, only date information was available in our DAD records – as is common for data provision by Population Data BC. The missing time component obfuscated detailed estimates of the temporal gap between records, but is a common limitation in extracts of the Canadian hospitalization datasets provided for research purposes [18, 20], and may occur in other regions too. The Hospital transfer flag was indicated by two fields – “HospTO” (planned transfer destination) and “HospFROM” (planned transfer source). Although required for both facilities to record in interhospital transfers, in reality the unique hospital facility identifier (ID) values in both the “HospTO” and “HospFROM” fields are found to not always be populated [12, 20]. Moreover, on rare occasions, there have been discordant values, which may be due to data entry error, an unknown hospital identifier, or diversion during the actual transfer where the patient is sent to a location different than originally planned [12, 20].

Taking into consideration the number of data fields available in the hospitalization record, variation in data quality, and prior Canadian publications for HEoC definitions [12, 18,19,20,21], we examined various approaches to combine related hospitalization records into HEoCs. By default, all HEoC definitions combined hospitalizations that were fully nested inside, or overlapped by > 1 day with, another hospitalization; this is rarely observed. To identify sequential hospitalizations, two different options for date gaps were considered: a) 0 day (i.e., hospital discharge date = subsequent hospital admission date), or b) ≤ 1 day (0 day, or having a subsequent hospital admission date one day after a prior hospital admission date). To identify planned transfers, we considered four different requirements around transfer indication: (a) no indication required, (b) transfer indicated (at least one-way population of hospital transfer fields), (c) at least one-way matching of hospital transfer location IDs, or (d) two-way matching of hospital transfer location IDs. Manual checks were conducted for a handful of individuals and hospital transfer scenarios to ensure our methods were classifying episodes as intended, as part of understanding and refining the implementation of definitions. Therefore, we constructed eight distinct HEoC definitions, forming a nested hierarchy (visualized in Fig. 1, and described in Supplemental Table 1).

As no reference standard (e.g., chart review) was available to evaluate classifications by each HEoC definition, we compared definitions primarily on the percentage of records combined into multi-record HEoCs (HEoCs involving multiple hospitalizations), LoS, unplanned readmissions within 30-days, as well as the definition feasibility given the data quality limitations. We measured percentage of multi-record HEoCs as it indicates how readily a definition combined related hospitalization records together into sets, and since this measure directly relates to the count of hospitalizations/episodes, which is a measure used in prior work examining HEoC definitions [20]. Relatedly, we also reported hospitalization counts based on each definition. We considered how mean LoS varied by definition, as LoS is a common outcome measure in epidemiologic research [7] and a metric that has been used to compare HEoC definitions [20]. HEoC-level LoS was defined as the count of days hospitalized from the admission date to the discharge date for single-record HEoCs; for multi-record HEoCs this was from admission date of the first hospitalization until (and including) the discharge date of the final hospitalization. To ensure the date of admission contributed to the LoS, a value of one day was added by default to all LoS calculations. Thus, LoS = (HEoC end date - HEoC start date) + 1. We also computed the percentage of readmissions within 30 day of a prior hospitalization episode [12]. We estimated additional LoS values (standard deviation, median, first, third quartiles), and the number of hospitalizations within an HEoC. All patterns were examined separately for the PWH and PWoH cohorts. In sensitivity analyses, the percentage of multi-record HEoCs yielded by each definition was stratified by sex, as well as the year of hospitalization, and when considering all hospitalization types (acute, day surgery, and other). Example SAS code for identifying hospitalization episodes of care is available at https://github.com/sdemerson-epi. We analyzed the data using SAS 9.4 [38] and R 4.3.1 [39].

There were 56,455 hospitalization records for PWH (n = 10,826 people; 79.9% male) and 973,430 hospitalization records for PWoH (n = 299,053 people; 42.9% male). The median age at the time of first hospital admission was 41.3 years (Q1-Q3: 34.3-49.9) for PWH, and 42.9 years (Q1-Q3: 26.3-65.3) for PWoH. For PWH, 62.9% of records were from facilities in Vancouver Coastal Health Authority (home to Vancouver, BC’s largest city) whereas for PWoH this was 22.9%. Inpatients were typically admitted to a single facility then discharged from that same facility back to their residence: over 90% of HEoCs in both the PWH and PWoH cohorts entailed a single record with no hospitalization occurring ≤ 1 day thereafter.

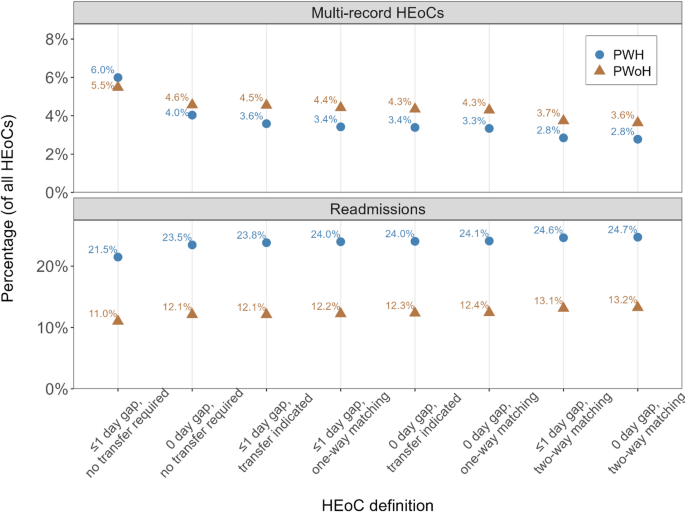

Depending on the HEoC definition, the percentage of multi-record HEoCs ranged from 2.8 to 6.0% among PWH and 3.6 to 5.5% among PWoH (Fig. 2; Table 1). The least stringent definitions (those requiring no transfer indication), combined records together more readily; for example, the ‘0 day’ definition, yielding the highest percentage of multi-record HEoCs among PWH (6.0%) and PWoH (5.5%). Conversely, the most stringent definitions (those requiring two-way agreement of hospital identifiers), combined records together less readily; for example, the ‘0 day, two-way matching’ definition yielded the lowest percentage of multi-record HEoCs among PWH (2.8%) and PWoH (3.6%). These patterns were maintained when stratifying by sex and year of hospitalization admission, as well as when including all hospitalization types (acute and otherwise; See Supplemental Information Figs. 2, 3 and 4). The percentage difference for episode counts relative to the count of raw hospitalization records ranged from -3.3% to -7.3% among PWH and from -4.3% to -6.7% among PWoH (Table 1). Within multi-record HEoCs, for both PWH and PWoH, approximately 80% of multi-record HEoCs contained two records (supplemental Fig. 3), indicating a single interhospital transfer was most common.

Comparison of the percentage of multi-record hospitalization episodes of care (HEoCs) and 30-day readmissions across definitions, among people with and without HIV in British Columbia, Canada (1992-2020)

PWH: People with HIV; PWoH: People without HIV. Multi-record HEoCs were episodes of care wherein at least two hospitalization records were combined together into an episode. Readmissions denote the percentage of all hospitalization episodes that had another hospitalization episode within 30 days; when using raw hospitalization records, the percentage of readmissions was 27.2% for PWH and 16.9% for PWoH

Most transfers in multi-record HEoCs occurred on the same day as indicated by the minimal difference in number of multi-record HEoCs yielded by the ≤ 1 day versus the 0 day gap versions of definitions requiring some transfer indication (e.g., comparing the ‘0 day, transfer indicated’ versus the ‘≤1 day, transfer indicated’). Between the two definitions using dates alone (‘same day’ and ‘≤ 1 day’), the ≤ 1 day gap provided a substantial increase in additional multi-record HEoCs identified over the 0 day gap – the ≤ 1 day gap definition yielded a 47% increase for PWH and an almost 20% increase for PWoH (Table 1). When at least one-way population of hospital transfer fields occurs, in rare cases hospital ID values were discordant but typically they did match. For instance, approximately 95% of multi-record HEoCs among PWH identified by the ‘≤1 day, transfer indicated’ definition were also identified by the ‘0 day, transfer indicated’ definition (1,914/2,025 multi-record HEoCs; for PWoH this value was approximately 95%: 42,232/44,251 multi-record HEoC; Table 1).

Across the eight HEoC definitions, mean LoS ranged from 12.7 to 13.9 days among PWH and 9.4 to 10.1 days among PWoH (Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. 2). The least stringent definitions (requiring no transfer indication) combined records together more readily (e.g., the ‘≤ 1 day’ definitions), and hence yielded the longest mean LoS among PWH (13.9 days) and PWoH (10.1 days). Conversely, the most stringent definitions, which required two-way agreement of hospital transfer IDs, combined records together less readily (e.g., the ‘0 day, two-way matching’ definitions), and yielded the lowest mean LoS among PWH (12.7 days) and PWoH (9.4 days). The percentage difference for mean LoS compared to the mean LoS estimated via the raw hospitalization records ranged from + 10.4% to + 20.9% (12.7, and 13.9, vs. 11.5 days, respectively) for PWH and from + 15.2% to + 23.4% (9.4, and 10.1, vs. 8.2 days, respectively) for PWoH (Table 1). For readmissions within 30 days, the percentage of all hospitalization episodes ranged from 21.5 to 24.7% among PWH, and 11.0 to 13.2% among PWoH (Table 1; Fig. 2). More readmissions were observed when the most stringent definitions were used (e.g., the ‘0 day, two-way matching’ definitions). The percentage reduction in readmission percentage ranged from -9.0% to -20.9% among PWH and -21.8% to -34.9% among PWoH depending on the HEoC definition, compared to when using the raw hospitalization records.

To more appropriately estimate key hospitalization measures, including LoS and readmissions, it is often preferred to combine related hospitalization records into HEoCs. Moreover, no prior work had examined methods to define HEoCs among PWH despite this group demonstrating distinct healthcare and hospitalization use patterns from the general population. In this study, we aimed to address this gap by comparing several definitions to create HEoCs among samples of PWH and PWoH. Further, we quantitatively demonstrated how this methodology helped avoid inflating hospitalization counts and readmissions while also helping avoid underestimating mean LoS compared to using raw hospitalization records. Across the eight definitions, patterns were similar between PWH and PWoH: Stringent definitions yielded the smallest percentage of multi-record HEoCs, shortest LoS, and the highest percentage of readmissions, whereas the least stringent definitions (requiring only dates) yielded the highest percentage of multi-record HEoCs, longest LoS, and smallest percentage of readmissions.

For general use purposes, it is important to use a pragmatic, balanced approach. Therefore, we recommend using the definition of at least a one-way population of transfer location identifiers within a ≤ 1 day gap (i.e., the ‘≤1 day, transfer indicated’ definition). This was a balanced definition based on the percentage of multi-record HEoCs, mean LoS, and percentage of readmissions; more stringent than the dates-only definitions, but the least stringent of the definitions requiring indication of a planned transfer. Additionally, its transfer indication aligns with that suggested by CIHI [21] and parts of the Fransoo et al. [20] definition, and choice of date gap (between hospitalizations) aligned with criteria of several published approaches [18, 20, 21]. This definition permits flexibility regarding delayed transfer gap timings, such as late night transfers that occur around midnight and span multiple dates, long distance transfers, and scenarios where the patient must wait a day until the receiving facility is able to accept them. Our recommended definition also requires some indication of a transfer having been intended, rather than requiring exact matching. Such flexibility is beneficial for researchers aiming to account for rare data entry errors in the transfer location or current hospital field and scenarios where diversion resulted in the receiving hospital differing from that intended. In summary, our recommended definition provides a more balanced set of criteria compared to what was previously available in the literature, offering more pragmatic, flexible requirements regarding the gap between hospitalizations and indication of a transfer. Should a research question align with the assumption that readmissions be included within a multi-record HEoC, then using a dates-based HEoC definition may be worth considering. However, it is important to recognize potential impacts of the misclassification of transfers as readmissions from using that definition.

Strengths of this work include the representative population-based samples of PWH and PWoH, and scope of almost three decades of hospitalization data within a single province with public healthcare. The source data for hospitalizations (the DAD) has also been found to be of generally high quality, based on re-abstraction analyses [37]. Although our study focused on a single Canadian province, we believe the principles underlying the definitions considered and the patterns may be useful for other contexts – particularly given the data structure of the DAD is similar to other countries [15,16,17]. The similar within-group patterns suggest that these definitions likely function similarly for two distinct health populations, both PWH and PWoH. We believe this study contributed both in providing a methodologic framework for creating HEoCs for HIV research (including comparative work between PWH and PWoH), but also more broadly in demonstrating the impacts of different HEoC definitions on hospitalization metrics for general use, with potential applications to other populations and settings. Accordingly, understanding how these definitions may function for other population and disease groups, and other geographic regions, may be an important avenue for future research.

Limitations included the lack of hourly discharge/admission time in the DAD extract provided from Population Data BC obfuscated more nuanced examination of temporal gaps between hospitalizations and prevented us from reproducing some aspects of prior published approaches. We also lacked an external reference standard source of information about transfer or readmission status (e.g., manual hospital chart review), which may have provided an additional source of information to classify hospitalization records. Additional indication of intended transfer or unplanned readmission can be sourced from the separation disposition field (nature of hospital discharge), the readmission field, and the transfer-based diagnostic code. These fields were not incorporated due to important data limitations. First, the separation disposition field was not considered in our work because, before April 2001, it did not contain information on transfers – indicating only whether a person was alive at discharge. Secondly, the readmission flag is limited to same-facility readmissions, and provided a date gap (< 5 or < 15 days) too broad for the gaps considered in our definitions (and in all five of the Canadian HEoC sources reviewed definitions [12, 18,19,20,21]). Further, we lacked complete data on facilities providing care outside BC, so were unable to validly identify the rare scenarios of interprovincial or international transfers. Although the DAD contains a small percentage of records from non-BC residents and hospitalizations involving out-of-province transfers, these records were omitted. Moreover, a holistic “episode of care” is often broader than acute hospitalizations, including outpatient healthcare practitioner encounters, medications, emergency department visits. Therefore, future work may consider additional forms of healthcare beyond hospitalizations. For some scenarios an HEoC framework is not necessarily beneficial, such as estimating resource use from the hospital’s perspective.

Using hospitalization data from populations of people with and without HIV in a Canadian province, this work demonstrated that using the product of HEoC methodology, rather than the raw hospitalization record, as unit of analysis can help produce less biased measures of hospitalization-related indicators, including hospitalization counts, readmissions, and LoS.

The British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS (BC-CfE) is prohibited from making this dataset available publicly due to prohibitions in the information sharing agreement under which the data stewards provided the data to the BC-CfE. Code for constructing HEoCs is available from the authors on request.

- BC:

-

British Columbia

- CIHI:

-

Canadian Institute for Health Information

- DAD:

-

Discharge Abstract Database

- COAST:

-

Comparative Outcomes And Service Utilization Trends study

- HEoC:

-

Hospitalization Episode of Care

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- LoS:

-

Length of stay

- PWH:

-

People with HIV

- PWoH:

-

People without HIV

The authors thank the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, BC Ministry of Health, BC Vital Statistics Agency, and the institutional data stewards for granting access to the data, and Population Data BC, for facilitating the data linkage process.

COAST is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, through an Operating Grant (#130419), the National Institutes of Health, a Foundation Award to RSH (#143342) and support from the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS.

Ethics approval for the COAST study was granted from the University of British Columbia/ Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board and Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics (H09-02905; H22-0875). The study complies with the BC Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) and did not require informed consent (i.e., informed consent was waived as per ethics boards approvals) as it is conducted retrospectively for research and statistical purposes only using anonymized data. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Not applicable.

All inferences, opinions, and conclusions drawn in this manuscript are those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the data stewards or the funders.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Emerson, S., McLinden, T., Sereda, P. et al. Identifying hospitalization episodes of care among people with and without HIV in British Columbia, Canada. BMC Med Res Methodol 25, 161 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-025-02602-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-025-02602-5