"I Was Instantly Galvanised": '60s Super Penelope Tree Recalls Witnessing The Birth Of Boho Style | British Vogue

As the only child of an American mother and British father, I grew up in New York but spent every June and July in London with my parents, who led a hectic social life and largely left me to my own devices. I had one friend from home, Susie Cooke, who was in a similar situation, so we hung out together, mostly unsupervised. Since life at our respective New England boarding schools was heavily rule-bound, we looked forward to London all year.

Then, in 1963, The Beatles burst onto the airwaves. The way I saw the world changed completely. During three successive London summers, Susie and I witnessed Vidal Sassoon haircuts, Mary Quant make-up, wildly abbreviated skirts and cool trouser suits gradually becoming de rigueur for most women under 40.

In the summer of 1967, when I was 17, I landed a job as a reader at a publishing house, while lodging with an uber respectable landlady in Park Walk, Chelsea. To her patent disapproval, every morning before work I applied pale foundation, painted eyelashes onto my bottom lids and donned my shortest skirt. No one could have accused me of exercising too much diligence when it came to my job. I lived for my Friday wage packet of £8.50, and the weekly pilgrimage to Biba where an entire outfit could be bought for a fiver. However, on the bus heading down the King’s Road, I soon noticed that the coolest kids on the street had more or less ditched the mod aesthetic and were turned out in flowing attire recalling a more romantic age. I was instantly galvanised.

It wasn’t long before I tracked down the source of this new look – the Chelsea Antique Market – situated in a huge rabbit warren of a building not far from my digs. Inside, there were a maze of stalls selling an array of antique jewellery, books and maps, Turkish carpets and art nouveau lamps. On the ground floor, a men’s vintage clothes stall was stuffed with ruffled Byronesque shirts, pre-1920s military jackets and velvet bell-bottoms. Jimi Hendrix and The Rolling Stones were poster boys for this look – soon it was everywhere.

On the first-floor landing, a dimly lit grotto with a dizzying display of vintage clothes suspended four or five layers deep from ceiling to floor became my favourite London haunt. Couture dresses in mint condition, from Schiaparelli and Poiret, hung alongside sequined tops à la Josephine Baker, exquisitely beaded boleros and delicate chiffon dresses from the 1930s. On the brightly painted shelves were piles of Fair Isle jumpers and cut-velvet shawls. Everything was jumbled together to the point it was almost impossible to distinguish one piece from another. There was no space for a changing room, so if you wanted to try something on, you had to strip off in front of whoever happened to be there.

Both shops were owned by Vern Lambert, a shy ex-accountant from Melbourne, who championed vintage at a time when very few people were interested. Apart from a brief nod to clients while he sorted through piles of old clothes on the floor, Vern left customer service to his flamboyant Swedish assistant, Ulla, and Jenny Kee, with whom I became great friends. Before long, Jenny had filled me in about Vern, who she idolised. He had begun his career selling art nouveau vases in a King’s Cross gallery, when he came across a trunk of beaded 1920s dresses and hung them up as decoration. They proved to be much more popular than the vases, and he sold the lot.

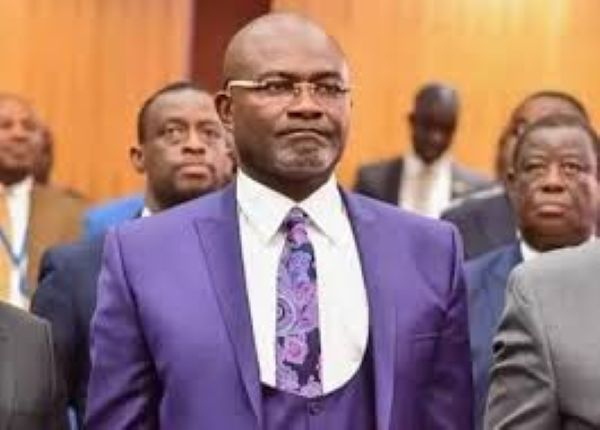

Penelope Tree photographed in May 1968.

BettmannVern employed a network of rag-and-bone men who scoured the attics of stately homes, country houses and local auction houses for old clothes that no one wanted. He also haunted the auction house circuit himself, once securing a large cache of costumes from the Ballet Russes from Sotheby’s that he sold on to his clientele (which included Keith Richards, Anita Pallenberg, Brian Jones, Marianne Faithfull and Mick Jagger) for peanuts.

“When the clothes aren’t in perfect condition,” Kee told me, “Vern alters them to make hybrids.” Like the bias-cut chiffon dresses with billowing sleeves I lusted over, as well as his bargain patchwork skirts made from floral print crepes. By the time London had become my full-time home in 1968, the bohemian look had taken off. Every Saturday, the Chelsea Market and shops like Hung on You and Granny Takes a Trip throbbed with musicians and models keen to make the multi-layered, globe-trotting look their own, subsequently influencing an entire generation to dress like them.

“The fashion world is in a state of anarchy!” Nova magazine declared, as the counterculture appeared to eclipse the status quo in every sphere. For the first time, young people were travelling to Asia and North Africa in large numbers, bringing back embroidered textiles and local jewellery. Designers such as Ossie Clark and Antony Price absorbed vintage elements into their own creations, which are among the most sought-after vintage labels in circulation today.

Meanwhile, Vern met the legendary Italian stylist Anna Piaggi and they fell madly in love. “It was style meets style,” Kee remembers. “Vern’s encyclopaedic knowledge of fashion history ignited Anna’s love of vintage clothes – she became his muse.” Together, the immaculately turned-out couple rose most mornings at 4am – with their flashlights on high beam – to scour Bermondsey for outstanding pieces.

After helping curate Fashion: An anthology by Cecil Beaton at the V&A in 1971, Vern moved to Milan with Piaggi. I also moved, scores of times, including to Sydney for a spell, where I reconnected with Jenny Kee, by then a celebrated Australian designer. Consequently, out of all the pieces I bought from the Chelsea Market, I’ve only managed to hold onto one single intricately embroidered Romanian shirt, which I still wear every summer.

In the ’90s and noughties, a new iteration of boho chic emerged, spearheaded by Mairead Lewin, who made the look fresh by customising vintage pieces for Kate Moss, Sienna Miller, Naomi Campbell and others. “For a while it was a niche style,” she told me. “I had fun buying from flea markets in LA, Peru, France – the wilder shores of shopping. Many of the fabrics I fell in love with – rare crepes, devoré silks, cut velvets – are not available anymore.” There are, she says, still gems to be had, but online vintage trading has placed many prized piece out of reach for many. “Ever since stars started wearing vintage on the red carpet, you see Galliano dresses made in 1998 going for £20,000,” Lewin adds. I gulped, thinking back on how Vern sold 1950s Dior dresses for £5 because their voluminous skirts took up too much room in his shop.

Boho fashion fan Sienna Miller in 2003…

Dave Benett/Getty Images… And at Chemena Kamali’s autumn/winter 2025 Chloé show.

Jacopo Raule/Getty ImagesToday, it is a thrill to see the return of a more romantic and individualistic style of dressing. This third wave of bohemian chic is unique to 2025, reinterpreted by gifted vintage upcyclers including Lewin, and by fashion houses such as Valentino, Saint Laurent and Chloé, which continue to create exquisite clothes made to last and to be cherished – perhaps in surprising new ways, by future generations of treasure seekers.