BMC Public Health volume 25, Article number: 1155 (2025) Cite this article

The global epidemic of overweight and obesity appears alongside numerous diseases. As electronic personal health information (ePHI) technology becomes more prevalent, understanding its relationship with health behaviors and how this relationship may differ across physical groups becomes increasingly relevant.

Using secondary data from the National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) 2020, this study examined the relationships between ePHI technology use, obesity preventive behaviors (e.g., physical activity, alcohol consumption, and diet control), and risk perception of obesity, considering body weight as a potential moderator.

The patterns between ePHI technology use and obesity preventive behaviors differed across behavior types and body weight groups. Higher ePHI technology use was associated with increased physical activity (b = 5.98, bp = 0.44, p < .01) and diet control (b = 0.03, bp = 0.28, OR = 1.11, p < .001), while no significant relationship was observed with alcohol consumption. The relationship between ePHI technology use and risk perception of obesity was weaker among the obese group (b = -0.03, bp = -0.11, p < .05). The indirect relationship between ePHI technology use and physical activity varied by body weight, showing stronger associations in the underweight group (95% CI [0.03, 2.77]) and weaker associations in the obese group (95% CI [-1.14, -0.04]).

The findings suggest more limited relationships between ePHI technology and health behaviors than previously anticipated. Physical activity and dietary regulation showed modest associations with ePHI technology use, while alcohol consumption showed no significant relationship. Overweight and obese individuals did not show a higher risk perception of obesity or greater engagement in preventive behaviors compared to those of healthy weight. These findings highlight the importance of developing a more nuanced understanding of ePHI technology's role in health-related contexts.

The escalating “global epidemic” of overweight and obesity represents a pressing public health challenge, with projections indicating a worsening trajectory despite recent estimates categorizing nearly half of the global adult population as overweight [1, 2]. These conditions are strongly associated with a heightened risk of diseases, including cancer, and impose a substantial economic burden on healthcare systems and governments worldwide [3, 4]. However, both overweight and obesity are largely preventable. Evidence suggests that adopting a combination of regular physical activity, a nutrient-dense balanced diet, and moderation in alcohol consumption can effectively mitigate excessive weight gain [5, 6]. Consequently, prioritizing population-level interventions to promote these evidence-based lifestyle modifications is essential to curbing the obesity crisis and its downstream health and socioeconomic consequences.

Within the domain of disease prevention, information communication technologies (ICTs) are increasingly integrated into modern healthcare, leading to the flourishing of electronic personal health information (ePHI) technology [7]. While existing studies underscore the potential of such technology to facilitate positive health-related behavior change [8, 9], evidence regarding its efficacy in obesity prevention remains equivocal. This inconsistency may arise from heterogeneity in how body weight subgroups perceive obesity-related risks and interact with ePHI technology, coupled with variations in how these technologies frame health behaviors. For instance, research demonstrates that weight-related perception biases across body weight categories influence individuals’ risk appraisal processes [10, 11], yet few investigations explore how body weight moderates the association between ePHI technology use and the adoption of preventive behaviors. Additionally, the framing of ePHI technology — specifically whether they emphasize physical activity, dietary habits, or alcohol moderation — critically shapes risk perception and subsequent behavioral outcomes [12, 13]. Despite known discrepancies in the framing of preventive behaviors within ePHI platforms [14, 15], comparative analyses of their differential impacts remain scarce.

Two remaining gaps warrant further investigation: (1) limited understanding of how ePHI technology effects vary across distinct preventive behaviors, and (2) insufficient attention to differences in risk perception and behavior change among body weight subgroups using ePHI tools. To address these gaps, this study examined how ePHI technology use differentially influences physical activity, dietary control, and alcohol consumption while investigating whether body weight moderates these relationships by mediating obesity risk perception. By integrating behavioral specificity with weight-based moderation, this research offers novel insights for designing targeted health interventions and advancing precision public health strategies.

ePHI technology use and preventive behaviors

ePHI technology encompasses ICTs that enable individuals to proactively acquire health knowledge, self-monitor their well-being, and engage with healthcare providers [7]. While commonly categorized into four domains — online patient-provider communication (OPPC), health information management (HIM), mobile health for self-regulation (MHSR), and social media for health information (SMHI) [16] — these technologies coalesce around two principal functions: (1) monitoring, managing and analyzing personal health status and behavioral patterns; (2) acquiring and exchanging health information from either health communities or professionals.

HIM and MHSR prioritize self-monitoring of physical and medical conditions, alongside preventive actions facilitated by wearable devices and mobile applications. These technologies track health-related behaviors and deliver real-time feedback [17, 18], enhancing personal health management. Evidence supports their efficacy in obesity prevention and weight loss interventions [19, 20]. Conversely, OPPC and SMHI enable health information exchange via digital platforms, improving patient-clinician communication [21] while fostering health literacy and community engagement [22]. They also promote the uptake of health-related apps and devices [23]. However, social media platforms also propagate weight-related stigmatization, often associating obesity with personal irresponsibility [14, 24, 25], a dynamic that may paradoxically motivate preventative behaviors to avoid social censure [26].

Despite functional distinctions, empirical evidence consistently links ePHI technologies – including smartphones, wearables, and social platforms – to improved health behaviors [27, 28]. While questioning persists regarding their efficacy and potential adverse effects [29], the prevailing consensus underscores their role in fostering preventative actions, particularly in weight management [8, 9]. Based on the aforementioned, the first hypothesis proposed by this study was:

H1: People who use ePHI technology more extensively are more likely to engage in preventative behaviors.

The mediating role of risk perception of obesity

In the process of ePHI technology use influencing preventive behavior, risk perception — an individual’s subjective evaluation of a health concern [30] — plays a mediating role, as evidenced by numerous empirical studies [31,32,33]. Individuals’ risk perception of obesity is determined by their knowledge of obesity [34] and subjective assessment of their own body weight [35]. Both of these factors are also influenced by their use of ePHI technology, which facilitates tracking changes in body weight and acquiring knowledge related to obesity [36]. Research evidence demonstrates that risk perception plays a significant role in shaping individuals’ preventive health behaviors, as evidenced by a growing body of research grounded in established health behavior frameworks. These include the protection motivation theory [37], the health belief model [38], and the extended parallel process model [39].

From the perspective of health information access, the content within ePHI technology often portrays obesity negatively due to its association with various diseases, including cancer [24, 40]. Therefore, individuals who frequently use these technologies are more likely to develop an increased risk perception of obesity. Besides, individuals who use ePHI technology to monitor their body weight may influence their perceived body weight, potentially impacting their risk perception of obesity. However, relevant studies on this effect remain scarce. The heightened risk perception of obesity influences the extent of preventive behaviors that individuals engage in, as numerous empirical studies have identified, such as those related to health information seeking and physical activity [41, 42]. Consequently, the second hypothesis proposed in this study was:

H2: The association between ePHI technology use and preventive behaviors is positively mediated by the risk perception of obesity.

The moderating role of body weight

Numerous empirical studies have investigated how information processing varies among different groups of people, revealing distinct influencing mechanisms on risk perception. It is influenced by the factors related to personality and the environment, as indicated by previous studies [43,44,45]. Consequently, it is crucial to consider individual differences when discussing the influence of ePHI technology use on risk perception in obesity studies. However, although existing research has demonstrated that weight group influences self-perception of weight and obesity risk [10, 11], the role of this factor in shaping the impact of ePHI technology use on risk perception of obesity is under-explored.

Concretely, individuals with healthy body weights express more concern about their weight than those who are overweight or obese [46]. Additionally, overweight or obese individuals may underestimate their weight, while those of healthy weight may overstate it [47]. This misperception contributes to survivorship bias among overweight or obese people. For instance, overweight children are more optimistic about obesity than their normal-weight counterparts [48]. Similar trends are observed in adults, with overweight individuals often underestimating obesity-related disease risks [35]. Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed for this study:

H3a: Underweight adults using ePHI technology will report a higher risk perception of obesity compared to healthy-weight adults.

H3b: Overweight adults using ePHI technology will report a lower risk perception of obesity compared to healthy-weight adults.

H3c: Obese adults using ePHI technology will report a lower risk perception of obesity compared to healthy-weight adults.

Comparison of different obesity preventive behaviors

Advocacy for diverse health behaviors varies, as individuals hold distinct perceptions of these behaviors [49]. Furthermore, various sociocultural factors influence the connection between risk perception and health behaviors [50, 51]. Therefore, this study categorizes obesity preventive behaviors into physical activity, alcohol consumption, and diet control. By comparing predictive models across these behaviors, it aims to gain comprehensive insights into the impact of ePHI technology use and body weight in obesity prevention advocacy.

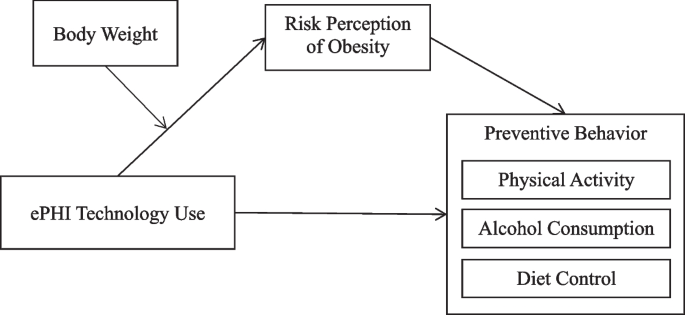

Besides, ePHI technology varies in their framing of physical activity, alcohol consumption, and diet control, leading to differences in their effectiveness. While many ePHI technologies underscore the significance of these behaviors in obesity prevention [52, 53], those with social features may have distinct impacts. Issues related to overweight and obesity are often linked to physical activity and diet, but alcohol is rarely addressed in their content [14]. Notably, in American culture, alcohol consumption is often encouraged [54]. Despite a growing awareness of the dangers of alcohol on social media, the likelihood of significant change remains relatively low [15]. See Fig. 1 for the conceptual model.

Consequently, this study proposed the following hypotheses and research questions:

H4a: People who use ePHI technology to a greater extent are more likely to engage in longer periods of physical activity, and this is positively mediated by the risk perception of obesity.

H4b: People who use ePHI technology are less likely to drink alcohol, and this is negatively mediated by the risk perception of obesity.

H4c: People who use ePHI technology to a greater extent are more likely to achieve diet management, and this is positively mediated by the risk perception of obesity.

RQ1: Do the effects of ePHI technology and risk perception of obesity on the three types of preventive behaviors—physical activity, diet control, and alcohol consumption—differ?

This study utilized secondary data from the National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), an annual, self-administered, cross-sectional survey representative of US adults. HINTS targets adults aged 18 and older and is administered among the civilian, non-institutionalized U.S. population. This study used the data from HINTS 5 Cycle 4, which was conducted between February and July 2020. The total number of addresses selected for Cycle 4 amounted to 15,350: 11,050 from the high minority stratum and 4,300 from the low minority stratum. The study included 3,865 respondents (see Table 1 for more detailed sociodemographic information), resulting in a household response rate of 36.7% [55]. As HINTS is a public and deidentified data set (can be downloaded through https://hints.cancer.gov/), the current study was not considered human subjects research. Information about informed consent and participant compensation from original HINTS data collection periods is published online (see https://hints.cancer.gov/).

Dependent variables

Physical activity was measured using two questions [56]. The first asked respondents about their weekly frequency of moderate-intensity exercise, such as brisk walking or average-speed cycling, excluding weightlifting. Responses ranged from “0 = none” to “7 = 7 days per week”. The second question asked about the typical duration of exercise on active days, measured in “minutes per day”. The product of these two responses provided the average weekly exercise duration in “minutes per week”.

Alcohol consumption was measured by two questions [57, 58]. Respondents were first shown a graphic illustrating “one drink of alcohol”, defined as 12 oz of beer, 8 to 9 oz of malt liquor, 5 oz of wine, or a 1.5-oz shot of 80-proof spirits. They were then asked how many days per week they consumed at least one alcoholic drink in the past 30 days, with responses ranging from 0 to 7 days. Additionally, they reported the average number of drinks consumed on drinking days. The product of these two responses provided a measure of alcohol consumption in “average drinks per week”.

Diet control was measured by a single question, asking respondents if they noticed the calorie information on the menu during their latest visit to a fast food or sit-down restaurant [59, 60]. Responses were binary: “0 = No” and “1 = Yes”.

Preventive behavior was measured by combining three variables: physical activity, alcohol consumption (where higher scores mean less alcohol consumption), and diet control [61]. Assuming equal health benefits from 150 min of weekly physical activity, alcohol abstinence, and calorie awareness, the scales for these behaviors were converted to percentages. These behaviors were proportionally represented in this variable, which has a 4-point scale from 0 to 3. A higher score indicates increased preventive behavior.

Mediator

Risk perception of obesity, an individual’s subjective assessment of a health concern, is crucial in determining the disease severity [62]. Therefore, the risk perception of obesity was measured using two questions about the perceived contribution of being overweight or obese and adult weight gain to cancer [41]. Responses were given on a 4-point scale: “1 = Not at all”, “2 = Don't know”, “3 = A little”, and “4 = A lot”. A higher average score of these measurements for this variable indicates a higher perceived risk of obesity. Cronbach’s α was 0.94.

Independent variables

ePHI technology use was measured by querying respondents about their use of electronic devices for health-related activities and their internet usage for health information sharing, online health issues forum participation, and health-related video viewing in the past 12 months [15, 63]. Responses were coded on a 2-point scale (“0 = No” and “1 = Yes”) and combined to create a 12-point scale, with a higher score indicating greater ePHI technology use.

Moderator

BMI was calculated from respondents’ reported height and weight. The sample was divided into four groups based on BMI: underweight (0 ≤ BMI ≤ 18.5), healthy weight (18.6 ≤ BMI ≤ 24.9), overweight (25 ≤ BMI ≤ 29.9), and obese (BMI ≥ 30), with healthy weight as the reference group [64, 65].

Control variables

Five sociodemographic variables (age, gender, education level, annual family income, and race) and two subjective variables (perceived health status and social trust) were used as control variables. Perceived health status was argued on a 5-point scale from “1 = poor” to “5 = excellent”. Social trust was measured by trust in information about cancer from five different sources, rated on a 4-point scale from “1 = not at all” to “4 = a lot”. The average score of these items indicates the level of the respondents’ trust in health information sources.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26 and PROCESS version 4.1, with linear regression testing all hypotheses. Due to diet control being a nominal variable, both logistic and linear regression were used for testing related hypotheses [66, 67]. To account for potential violations of the normal distribution assumption in linear regression, bootstrapping with 5,000 samples was used, allowing for model stability testing and mediation hypothesis testing [68, 69]. To enable effect size comparison across disparate units, this study adopted percentage coefficients (bp), whereby all variable values were converted into percentages within their conceptual range, thus standardizing them onto a common measurement scale from 0 to 1 [70, 71]. See Table 2 for the variable description.

This study found a positive correlation between ePHI technology use and preventive behavior, which is mediated by risk perception and obesity (H1 and H2). Significant positive associations were found for ePHI technology use on both preventive behavior (b = 0.07 bp = 0.25, p < 0.001) and risk perception of obesity (b = 0.05, bp = 0.17, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, risk perception of obesity was found to have a significant positive cross-sectional effect on preventive behavior (b = 0.11, bp = 0.11, p < 0.01), and a significant mediation cross-sectional effect of risk perception of obesity was also found in the relationship between ePHI technology use and preventive behavior (b = 0.01, bp = 0.02, 95% CI [0.002, 0.01]).

H1 and H2 tests provided insights into the influence process of ePHI technology use on general preventive behavior. To explore differences in their impact on specific preventive behaviors (RQ1), physical activity, alcohol consumption, and diet control were examined as dependent variables, leading to H4a, H4b, and H4c. H4a, which hypothesized that increased ePHI technology use would extend physical activity periods (b = 5.38, bp = 0.39, p < 0.01) and be mediated by the risk perception of obesity (b = 0.60, bp = 0.04, 95% CI [0.13, 1.14]) was supported. H4b, predicting reduced alcohol consumption with greater ePHI technology use and negatively mediated by risk perception of obesity, was not supported (95% CI contained zero). H4c, anticipating an increased probability of diet control with greater ePHI technology use and positively mediated by risk perception of obesity, was fully supported in both logistic and linear model testing (see Model 3 in Tables 3 and 4). Moreover, the total effect of ePHI technology use, as well as the effect of risk perception of obesity, is more pronounced on physical activity than diet control.

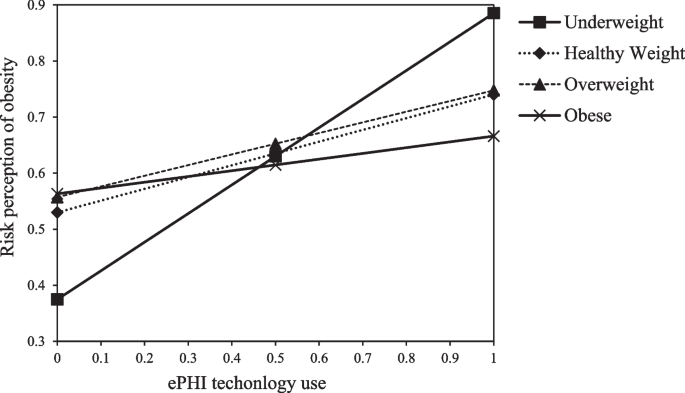

H3a, H3b, and H3c were formulated to examine if the relationship between ePHI technology use and risk perception of obesity varied across different body weight groups. A significant negative effect of ePHI technology use on risk perception was observed in the obese group (b = −0.03, bp = −0.11, p < 0.05), but no moderating effect was found for underweight or overweight groups. Figure 2 visualizes the impact of boy weight on the effect of ePHI technology use on risk perception of obesity.

Moderation Effect of Different Body Weight Groups on the Relationship between ePHI Technology Use and Risk Perception of Obesity (Percentage Coefficient)

Table 5 revealed that body weight moderated the indirect relationship between ePHI technology use and obesity preventive behaviors through the risk perception of obesity. For physical activity, significant moderation effects emerged in the underweight (95% CI [0.03, 2.77]) and obese groups (95% CI [−1.14, −0.04]), but not in the overweight group (95% CI contained zero). Compared to healthy-weight and overweight individuals, the indirect relationship was stronger among underweight individuals and weaker among obese individuals. These findings suggest that risk perception of obesity has a stronger association with physical activity among underweight ePHI technology users and a weaker association among obese users. Similar patterns were observed for overall obesity preventive behavior but not for alcohol consumption or diet control (see Table 6).

This study examines the relationships between ePHI technology use, risk perception of obesity, and obesity preventive behaviors. It investigates three areas: the associations between ePHI technology use, risk perception, and three types of health behaviors (physical activity, diet control, and alcohol consumption); the relationship between ePHI technology use and risk perception of obesity across different weight groups; and how body weight may interact with ePHI technology use concerning obesity preventive behaviors.

Consistent with prior research, this study further substantiates the assertion that the escalating adoption of ICTs significantly contributes to the enhancement of health behaviors at an individual level [28, 72, 73]. The results revealed that increased use of ePHI technology enhanced risk perception of obesity and promoted preventive behaviors, particularly physical activity and diet control. The impact on physical activity is significantly more pronounced, suggesting a prevalent belief in its superior effectiveness in weight reduction. This could be attributed to the fact that despite both obesity preventive behaviors – physical activity and diet control – being framed as equally significant in reducing overweight and obesity by ePHI technologies [14], these technologies facilitate easier tracking and feedback on physical activity compared to dietary behavior [74]. However, in the prediction of alcohol consumption, this study found that ePHI technology use and risk perception of obesity had no significant effect on alcohol consumption. This could be due to the US culture’s promotion of alcohol intake, which may counteract the benefits of ePHI technology promoting alcohol reduction [54]. Additionally, ePHI technology is less likely to associate alcohol with obesity concerns, leading to increased risk perception of obesity but not decreased alcohol consumption [14, 25, 75]. Even though recent years have seen a shift in opinion, the belief that moderate alcohol consumption promotes health persists [76].

In terms of population characteristics, this study observed similar relationships between ePHI technology use and risk perception of obesity across underweight, healthy weight, and overweight groups but noted a negative association in the obese group. For overweight individuals, ePHI technology use appears alongside body weight monitoring patterns [36, 56]. The weaker relationship observed in the obese group aligns with the literature on the body-positive movement [77]. The analysis also revealed that the indirect relationship between ePHI technology uses and preventive behaviors (both general and physical activity) through risk perception of obesity varied by body weight. This indirect relationship was stronger among underweight individuals and weaker among obese individuals compared to those of healthy or overweight status.

The relationship with overall preventive behavior showed moderate strength (bp = 0.25), with diet control showing a slightly stronger association (bp = 0.28), while physical activity exhibited the strongest relationship (bp = 0.39). These variations across behaviors align with different patterns of ePHI technology use, with no significant relationship observed for alcohol consumption behavior. In addition, while ePHI technologies showed positive associations with obesity prevention behaviors generally, these relationships appeared weaker among overweight and obese subgroups—populations with higher rates of obesity-related comorbidities. The data suggests that customized health-promoting features of ePHI technology show different patterns of association across weight groups. These patterns highlight the potential benefits of complementary external support and intervention when implementing ePHI technology among overweight and obese populations.

The analysis revealed modest indirect relationships between obesity preventive behaviors and risk perception of obesity. These findings align with literature suggesting limitations of fear and stigma-based approaches in obesity prevention, despite common associations between weight status, personal behaviors, and health outcomes in ePHI technology practices. Indeed, current ePHI tools often employ standardized risk communication approaches, which may not fully address factors such as self-efficacy, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control—variables that show strong associations with preventive behaviors in high-risk populations [78, 79]. Risk alerts alone show different relationships with behavior among users experiencing weight-related stigma. Future interventions might benefit from incorporating peer-support networks and skill-building modules, potentially supporting psychological factors related to health choices.

Like any study, this one has its limitations. One pertains to the examination of causal relations. Despite some academics questioning the causal relationship between risk perception and preventive behavior, this study could not examine it due to its reliance on cross-sectional data. Another limitation lies in the measurement of ePHI technology use. As this study amalgamated the various functionalities of ePHI technology into a single concept, the influence of specific functions on risk perception of obesity and changes in preventive behaviors may have been overestimated or underestimated. Future studies could examine how different types of ePHI technologies might show distinct patterns of association with various health behaviors. This would enhance our understanding of the effects of new media technologies in a multi-media environment on people’s health behaviors and the mechanisms that influence them.

This study provided empirical evidence on the impact of ePHI technology use on obesity preventive behaviors. It offered a comparative perspective to scrutinize the variations in the effects across different preventive behavior types and individuals of varying body weights. The study revealed that the use of the ePHI technology does not effectively promote physical activity and diet control and has no impact on alcohol consumption. Furthermore, it was not found that overweight and obese individuals had a higher risk perception of obesity, which did not subsequently lead to more preventive behaviors. Understanding these differences is critical to refining the integration of ePHI technologies into obesity prevention strategies, ensuring they are tailored to address behavioral heterogeneity gaps among diverse populations.

The health information national trends survey (HINTS) data can be downloaded through https://hints.cancer.gov/.

- ePHI:

-

Electronic personal health information

- ICTs:

-

Information communication technologies

- OPPC:

-

Online patient-provider communication

- HIM:

-

Health information management

- MHSR:

-

Mobile health for self-regulation

- SMHI:

-

Social media for health information

- HINTS:

-

Health information national trends survey

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

Not applicable.

Financial support was provided by the University of Oklahoma Libraries’ Open Access Fund. This study was also supported in part by grants from the Sun Yat-sen University, startup funding.

The data were publicly available and deidentified; therefore, the human research protection program of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center decided it did not require review by the institutional review board. The HINTS data ensure that participants provide informed consent for participation in the study.

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Ye, J.F., Song, Y.S., Lai, Y. et al. How do electronic personal health information technologies enhance obesity prevention behaviors? Examining the roles of obesity risk perception and body weight. BMC Public Health 25, 1155 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22225-1