Holding Onto a Lust for Life in a Post-Apocalyptic World: Jodie Comer, Ralph Fiennes, Danny Boyle and Alex Garland Chat '28 Years Later'

Rampant death. A destroyed world. When Cillian Murphy's (Small Things Like These) bicycle courier Jim awoke from a coma in a deserted British hospital 28 days after the rage virus leapt from chimpanzees in a biological weapons laboratory to spreading across the United Kingdom, that is what he found. The scenes of the Oppenheimer Oscar-winner's character wandering through an empty London in 2002's 28 Days Later — images that no one could fathom happening beyond the realm of cinema prior to the COVID-19 pandemic's earliest days — were stunning. So too was Danny Boyle (Yesterday) and Alex Garland's (Warfare) entire film, as Jim and the fellow survivors he stumbled across, including Naomie Harris' (Black Bag) Selena, Brendan Gleeson's (Joker: Folie à Deux) Frank and Megan Burns' (In2ruders) Hannah, tackled perhaps the most-important existential question there is: how does life go on?

That query is again on Boyle and Garland's minds 23 years later for audiences, but closer to three decades on inside the narrative of their stellar horror franchise. 28 Days Later initially received a sequel in 2007, but Boyle didn't direct 28 Weeks Later, nor did Garland pen the film's script. For 2025's resurrection of the saga, they're now back in their OG roles — as they once were when Boyle only had Shallow Grave, Trainspotting, A Life Less Ordinary and the big-screen adaptation of Garland's 90s must-read novel The Beach on his resume, and also before Garland became the helmer of Ex Machina, Annihilation, Men, Civil War and Warfare.

How life goes on interested this pair again in 2007 themselves, actually, but in a completely different movie. 2057-set sci-fi thriller Sunshine enlisted an impressively stacked ensemble — including Murphy again, another future Academy Award-winner in Michelle Yeoh (Wicked), 28 Weeks Later star Rose Byrne (Physical), plus Chris Evans (Materialists), his Marvel Cinematic Universe colleague Benedict Wong (Bad Genius), Hiroyuki Sanada (Shōgun) and Cliff Curtis (Kaos) — to portray astronauts attempting to save humanity from a dying sun. If Boyle and Garland had had their way, that would've sparked two more films. "Moonshine and Starshine. We never got to make them," Garland tells Concrete Playground. "So Sunshine was originally, there was this idea of it being a trilogy, but it didn't do very well. People like it a lot more now than they did on the day, or that's what it seems like, anyway," adds Boyle.

Returning to 28 Days Later's infection-ravaged UK with 28 Years Later is no mere consolation prize in the wake of Sunshine's trilogy never soaring beyond a concept. This visit to a post-apocalyptic Britain is a spectacular event in its own right — and also the beginning of a new trio of movies. 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple has already been shot, with Candyman and The Marvels' Nia DaCosta directing a Garland script, Boyle producing, Murphy set to feature and a January 2026 release slated. Everyone that sees 28 Years Later will be counting down the days. A currently untitled third picture, and fifth in the saga, is planned after that, which Boyle will hop back behind the lens on.

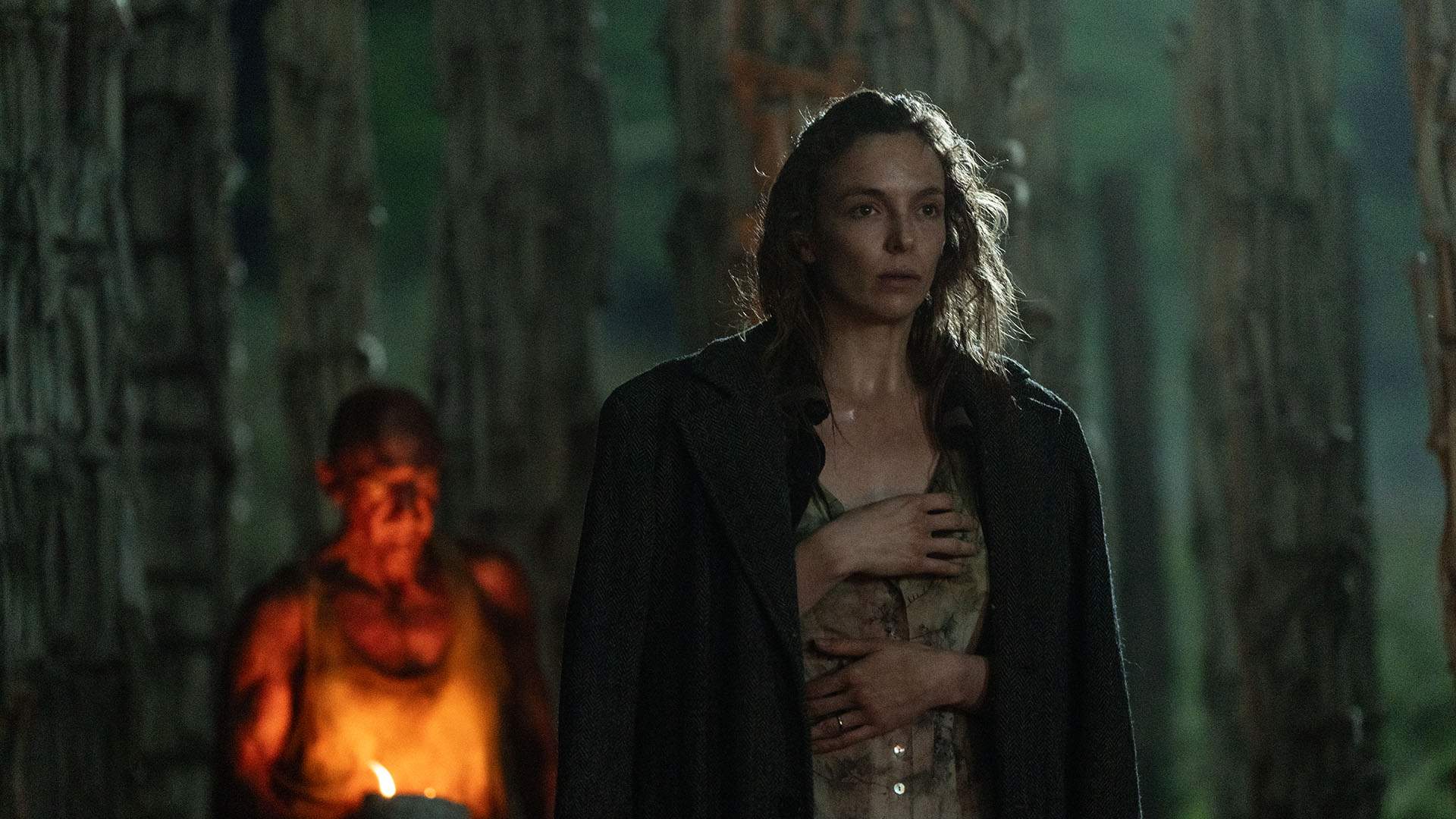

Existence endures in this franchise partly through human persistence in a Britain quarantined from the rest of the planet — and, for the community on Holy Island, through carving out a new normalcy. This northeast spot, which is only connected to the mainland via a sole causeway, is the only place that 12-year-old Spike (Alfie Williams, His Dark Materials) has ever known. But its people have a custom, taking its adolescents across the water to face the infected and prepare for an adulthood that requires venturing beyond the isle's walls for wood for fuel. The town has many traditions, in fact; however, this is where the film meets its protagonists, as Alfie sets off for a day trip with his dad Jamie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Nosferatu) while his ailing mother Isla (Jodie Comer, The Bikeriders) remains bedridden.

Not only how life continues but how people manage to subsist without modern medicine, or don't, is among 28 Years Later's concerns. Boyle and Garland's latest collaboration has brains — and heart, too, as it relays an immensely relatable story about coping with sickness regardless of the zombie-like creatures prowling rewilded landscapes. "I wanted the illness to feel believable," Comer advises. 28 Years Later also ponders what the passing of three decades means for societal attitudes, for young minds that've only existed since the rage outbreak and also for the infected themselves, as nature always evolves. A family drama, a coming-of-age film and, yes, a horror movie: all are alive within its frames, as is Garland's penchant for fraying and fracturing status quos.

Firmly remembering death is as much a part of 28 Years Later. Mortality has become utterly unavoidable for England's remaining inhabitants. Musing on it proves the same for the movie. Grief and loss, both everyday and on a mass scale, pulse through it, as does the distress of co-exisiting with uncertainty, and with death always surrounding you. Dr Ian Kelson (Ralph Fiennes, Conclave) helps give these themes an iodine-covered champion, assisting in the feature's balance of carnage with compassion in the process. "He sees the bigger picture," Fiennes tells us. Unsurprisingly, the actor adds to 28 Years Later's exceptional performances, with Williams and Comer among his clear company.

While there's no desolate cities here, then, 28 Years Later's visuals are every bit as memorable, meaningful and masterful as those in the flick that started it all, and possess the same just-can't-escape intensity. Boyle and also-returning cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle (My Penguin Friend) — who claimed one of Slumdog Millionaire's eight Oscars, as Boyle did for directing — have conjured up a new array of striking and terrifying imagery, filled with greenery and gore and sky-high monuments made of bones (over 250,000 individual replicas and 5000-plus skulls). Our chat with Boyle, Garland, Comer and Fiennes spanned giving the new film its own look, too, plus whether there was a Sunshine-esque plan for more 28 Days Later entries 23 years ago, contemplating mortality, towers of bones, conceiving of rituals and routines for a post-outbreak way of being, and more.

"Danny and I had a crack at a 28 Years Later film quite soon before this one. We worked on a script and worked something up, but just didn't feel it was right. There were some issues. Basically, it was it was too generic as a story.

And I think that, in a strange way, trying and failing was the last part of the puzzle towards coming up with this idea. And when this idea arrived, it just came in the form of a trilogy.

And I think stories, you slightly discover stories more than invent them. They just arrive not exactly fully formed, but with the core of them formed.

And the core of this was a trilogy — three separate but interrelated narratives that form an overall structure, because some characters will move through the films, basically."

"I think it was important to me in a sense. I wanted the illness to feel believable, though it was tricky — because she goes on such a journey, yet is so debilitated by her illness.

And she's very fortunate that she has her son to guide her and nurture her through, who often plays the kind of parental role.

But I would just say it was always very present within the script, so it was beautiful to explore, and trust and lean into Danny's direction, and hope that it felt believable — and that there were enough ebbs and flows and nuances throughout the time in which we spend with her."

"Rewilding is something that played into our hands, really — that we were able to find areas that looked like they hadn't been [impacted by humans].

There are lots of areas of Britain — as you can imagine, it's quite a small island — that have been agriculturalised, and you can see, either close or in the distance, the mark of man, really. But there's an area in the northeast that does remain untouched. It's not much good for anything, that's the opinion of people anyway, but it's perfect for filming.

And so we wanted to take these smaller cameras there, so we keep a light footprint and not disturb it too much. But also the technology has moved on so much now that these smaller cameras do allow you to use a widescreen format. There's enough resolution. And it means that you can have a statement that says quite clearly right from the early on that this is not a deserted empty city — which people might be expecting, because if it was a direct reference to the first film.

It's very much outside the cities. They stay — in fact, I think one of them says at one point 'we stay outside the cities and towns', implying that their safety is on this beautiful island, Holy Island. Which is a historic — it's where Christianity first arrived, I think, in the UK.

And it supports the perfect-size population for this kind of existence, about 100–150 people — where you don't need a system to run it. They just trust each other. They appoint their own leaders, and everybody knows each other and trusts each other.

And Harari [writer Yuval Noah] says it in the homo sapiens book [Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind], that when you get above about 150, you have to have a trust system to make everybody relate to something and trust through a system — which can be religion, or it can be money, or other values, for bartering."

"That was a great angle, because immediately it presents me, as Kelson, with the man who's accepted the reality of death. He's living with death, his mortality. And that makes him rather like a seer or sage or — he's kind of like a bit of a priest, in a way.

He sees the bigger picture. He talks about what the skulls had, that they were inhabited by the different souls — 'these eyes saw', 'these jaws spoke'. He's aware of the human soul. He's aware of the vitality of the human soul and the passing, how we pass from our earthly life into another life.

I think he's — and this is what I projected onto him — he feels that we must mark the passing. We have been. We have graveyards. We have symbols of those we have lost. And he's created a big symbol in this Bone Temple.

So I think he feels the need to acknowledge the lives that have gone. I think he's a bit like an artist or someone who's made this extraordinary installation in recognition of all the suffering that's gone on."

"A lot of it just stemmed from the idea '28 years later'. So then, if you know it's 28 years after this strange viral outbreak, there's stuff that just logically flows from that.

One of the things that logically flows is if you have communities that have stayed alive, well, they must have been able to defend themselves somehow. There's different ways you could defend yourself. It could be high walls, and it could be patrols and stuff.

But there is this island that Danny was just talking about, Holy Island, which is connected to the mainland by a causeway. So in high tide, it's separate, and there's only really one way you can get to the island across this across this road. And so that created a natural barrier where these people could live.

But then past that, to be honest, I don't really develop that. I would write some characters and a story about a community where people are using bows and arrows, and there's a mum and a dad and a child, but the fleshing out of that community — like 'what is their relationship to churches? What livestock do they have? How have they divided up their roles?', and even little details like 'what have they made into their own folklore?', like, for example wearing masks that represent infected — that's really Danny, and then the people he's working with, production designers and costume and makeup and so on, everybody just coming together to inhabit those bare bones.

I think a script is a blueprint. But then the rooms have to be filled with furniture and curtains are chosen, as it were. You can see the metaphor. And so it's not really my job, I suppose — just the superstructure."

"But one of the pleasures of doing it, though, and I think for audiences watching it, is the world-building — that you have to make all those decisions about how would they have survived, fed themselves.

Fuel was the big thing that we talked about. You'd need so much fuel, which is wood for them to burn. So they go over to the mainland and chop down trees. And England would basically slowly return to forest, which it was originally.

And they would scavenge, they would bring that fuel back — which is one of the dangers they have, and why they have to train their boys.

And it's very much a gender-separated society. They look back like that to an older era, to like the 50s. They train their boys, because they're going to have to go to the mainland to get fuel. And sometimes, maybe food — kill deer or whatever, because Britain would be overrun by deer, apparently. Because there's no natural predators."

"It practically is right now.

It is interesting. I think audiences detect logical consistency with these things, and also react against logical inconsistency. So, with world-building, it has to make sense. You have to believe in the interactions.

They don't all have to be laid out, but you can make imaginative leaps between all the things. And when they don't make sense, people spot it — like they spot bad visual effects. They just know it somehow and pull back."

"Something's not right, yeah."

"And I do think this film has a lot of unseen consistency in the way of that world that Danny and the team put together."

On the Energy That the Bone Temple Set with over 250,000 Individual Replica Bones and 5000-Plus Skulls — and the Film's Shooting Locations in General — Gave the Cast

"Well, it's funny, because the set felt so alive in many ways, in regards to the location and being right next to the running water. And there were lots of wind chimes made of bones, so there was just constantly this kind of music that was enveloping the space.

I also came to that set at the end of the shoot, when we were shooting those moments. So it really felt like we've heard so much about this place and this doctor, and then we were able to do our scenes with Ralph and explore that part of the material.

So it was really profound, actually. So much detail."

"Yes. It was a strong atmosphere. And the location itself, even with just as a location, even before the incredible Bone Temple, the location was beautiful.

We shot it in North Yorkshire, and I was going to work every day driving over the moors. It's stunning. It's a stunning place.

And I can see the other locations that Jodie and Alfie shot in are beautiful locations in the north of England."

28 Years Later released in cinemas Down Under on Thursday, June 19, 2025.