BMC Health Services Research volume 25, Article number: 872 (2025) Cite this article

The global public health crisis caused by COVID-19 in late 2019 was unprecedented. Due to their vulnerable population, nursing homes are a key epidemic response area. This study described the challenges and coping strategies of nursing home staff during COVID-19 and proposed recommendations for future public health crises in nursing homes.

A meta-synthesis was performed to address the research question: What are the experiences of nursing home staff from the perspectives of COVID-19? From the beginning until August 31, 2024, searches were conducted in five international databases (CINAHL, PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library) and three Chinese databases (CNKI, VIP, and Wanfang). Two reviewers used the Joanna Briggs Institute's (JBI) qualitative research checklist to evaluate each manuscript. The findings were synthesized using pragmatic meta-aggregators.

The meta-synthesis included 22 qualitative studies and four mixed studies, which including 906 participants was analyzed to identify 268 findings that were organized into 15 categories and combined into three syntheses. Three synthesized findings were identified: Challenges (sub-findings: challenges implementing epidemic prevention and control, resource shortage, negative emotions, inadequate departmental communication and coordination, lack of support, physical strain); coping strategies (sub-findings: role adaptation and redefinition, innovative solutions and technology, work organisation and cooperation, positive psychological service, seeking community and organisational support, Improving infection prevention awareness), and suggestions for future preparedness (sub-findings: Enhancing communication and decision-making in response to COVID-19 changes, Optimizing material supply channels and physical space, and increasing medical related team and training).

This study focuses on the COVID-19 experiences and coping strategies of nursing home staff. Key coping strategies include role transition and redefinition, with staff taking on additional tasks to ensure ongoing diagnosis and treatment; innovative concepts and technologies, such as remote healthcare and digital tools, reduce the risk of infection; and strengthening collaboration and cooperation, improving efficiency, and decreasing employee workload. Mental health services and social support can alleviate stress and promote health. Maintaining optimism among staff members necessitates community and organisational support, resources, and effective communication. The findings of this study have implications for nursing home practices and policies. Sanatoriums require PPE, medical supplies, and trained personnel. Encourage system and organisational transformation. Emergency preparedness and flexible workforce initiatives enhance organisational adaptability. Increase infection prevention awareness: Sanatorium employees should get continual infection prevention training. Exploring nursing homes Layout: Relevant departments should establish criteria for the physical layout of current and prospective nursing facilities to prevent basic infectious diseases.

According to the latest WHO data, COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has resulted in 70 million deaths globally [1]. Nursing home residents were at risk of severe infections and death during the Delta phase (summer 2021) and Omicron phase (winter 2022) [2]. On May 5, 2023, the WHO declared COVID-19 a "new normal", meaning it will become a chronic virus like the influenza virus [3]. COVID-19 illustrated more severe symptoms, spread more rapidly than the influenza pandemic, and resulted in a higher mortality rate [4]. Older adults, especially those with underlying conditions such as cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, and cancer, are at a higher risk of severe illness and death when infected with COVID-19 [5]. These older adults also have higher hospitalisation rates and case fatality rates compared to younger populations [6, 7]. Given that nursing home residents are mostly older people with chronic diseases, they remain highly susceptible to the impacts of COVID-19. Therefore, the "new normal" does not mean abandoning COVID-19 protection measures for older people, especially those in nursing homes.

Nursing homes are institutions that provide limited medical services to non-hospitalized patients, primarily medical, personal, physical therapy, occupational, and preventative care [8]. The incidence of COVID-19 cases and fatalities in nursing homes for older people has markedly varied due to factors including evolving knowledge and research reliability, viral mutations, medical infrastructure, population density, personnel and training, along with cultural and geographical disparities [9,10,11]. Developing countries (low- and lower-middle-income countries) were deemed more likely to bear the heaviest burden of the pandemic, mainly due to fragile healthcare systems, political instability, economic vulnerability, limited fiscal space, equipment shortages, among others [12]. This, however, appears not to have been the situation. For instance, the incidence of cases in the majority of African nations remains relatively low, accompanied with reported low mortality rates [13]. Previous studies pointed out that the present prevalence of cases in developing countries, which is lower than anticipated, was attributable to inadequate detection [14, 15]. The poor medical conditions in low—and middle-income countries lead to incomplete detection and inaccurate data, but it can still be inferred from the existing data that the situation in developed countries is more optimistic. The total people incidence of COVID-19 in Britain, India, Brazil and South Africa ranked first in Europe, Asia, South America and Africa, respectively [16]. COVID-19 incidences per nursing home bed ranged from 2.2% in Finland to 50% in the US and Europe [11].

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed numerous obstacles to the healthcare system regarding the medical requirements of facilities, particularly in nursing homes [17]. Living in a nursing home has also been found as an additional risk factor for infection and mortality due to a COVID-19 infection compared to living independently at home [18, 19]. In May 2020, more than half of COVID-19 deaths in France and Ireland were in nursing homes, with rates far higher in the United States and Canada [20, 21], and significant excess mortality in nursing homes in England and Wales [22]. Nursing home residents died 108 times more from COVID-19 than non-nursing home inhabitants in 2020 [23]. A systematic review of 49 research studies involving 214,380 individuals revealed that nursing home residents are vulnerable, exhibiting a 45% facility-specific incidence rate, a 23% case fatality rate, and a 37% hospitalization rate [5].

Four years post-COVID-19 epidemic, nursing homes globally have implemented various ways to address dangers and problems, ensuring the effective functioning of institutions and the well-being of staff and residents. During the initial outbreak and the global pandemic (late 2019 early 2021), nursing homes in many countries implemented restrictive measures during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in order to prevent an outbreak, such as strict no-visitor policies and placing infected residents into quarantine [24]. Despite the gradual liberalization of COVID-19 regulations in many countries around the world, daily life in nursing homes hasn't returned to normal in terms of interpersonal relationships, visitation, facility usage, and work stress [25, 26]. Numerous studies indicate that these measures significantly affect the health of residents and workers, contributing to increased loneliness, psychological stress, apathy, and depressive symptoms, potentially outweighing the benefits of preventing more infections [26, 27]. During the transmission phase following the establishment of the mutant strain (From the beginning of 2021 to the end of 2022), professional people increasingly recognized the significance of vaccination and natural immunity [28]. However, the benefits and drawbacks of administering the new coronavirus vaccine to older people with chronic illnesses still an controversial topic [29, 30]. In the post-epidemic era (Since 2023), despite the normalization of COVID-19, the staff and residents in nursing homes continue to experience significant psychological distress [31]. These psychological distress are associated with various variables, including the susceptibility of pension institutions and the elevated mortality and emergencies resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic over the past four years.

The rapid spread and complications of COVID-19 posed significant challenges to older people and also threatened the mental and physical health of health workers, especially those interacting with nursing home residents, who needed to be extra cautious [32, 33]. The lack of adequate and standardised personal protective equipment (PPE) put staff at increased risk of infection [33]. Anxiety, tension, and guilt were caused by the interdisciplinary staff's struggle to prevent infection and their fear of spreading the disease to their families and themselves [34]. Nursing home staff had to strike a balance between controlling COVID-19 and ensuring the quality of life of older adults [33]. Prevention measures implemented for preventing COVID-19 infection and transmission have led to conflicts between staff and older people family members [35]. Consequently, recognizing and incorporating the problems and strategies presented by the epidemic can enhance the effective response of nursing homes to similar emergency public occurrences in the future.

Since the outbreak of the epidemic, many studies have explored the health effects of COVID-19 and related restrictive measures. Nursing homes were already facing a high turnover rate, a continuous shortage of personnel and job burnout [36], and the COVID-19 epidemic has increased the difficulties faced by institutions [17]. To protect this workforce from the pandemic's long-term effects, we must first comprehend how COVID-19 has impacted employees'regular tasks. A qualitative research design is suitable for an in-depth understanding of the experiences of the population. Undoubtedly, such research plays an important role in enlightening nursing home staff on the significance, feasibility, and acceptability of measures to prevent the spread of the epidemic and promote health. After the initial literature review, it was found that, although many qualitative studies have reported the experiences of nursing home staff during the pandemic, no systematic reviews of the same have been conducted so far. Therefore, a systematic review of the existing research in this area could guide the transition of nursing home staff in addition to providing relevant suggestions for the management of public health crises in the future, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. To this end, the current study conducts a systematic review to identify and synthesise the available qualitative evidence pertaining to the challenges, coping strategies, and recommendations of nursing home staff during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This present systematic review protocol is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021279397). This qualitative systematic review was conducted in August 2024 using the meta-aggregation approach developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), which is an effective strategy to synthesise qualitative study findings [37].

We searched eight databases from the earliest date to 31 August 2024: PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Internet (CIKN), China Science and Technology Journal Database (Vip), and Wanfang Database. Truncation was used when retrieving entries with different word endings for the same keyword, for example: nurs* to retrieve nursing, nurses, nurse and so on. Boolean operators (OR/AND) were used to combine keywords. To search the PubMed electronic database, refer to Appendix S1.

Types of participants

This review only considered studies that focused on nursing home staff fighting COVID-19 in nursing homes, including physicians, nurses, administrators, and other workers who directly interact with older adults.

Phenomena of interest

The phenomena of interest for this review included the experiences of nursing home staff who engaged in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, which included challenges and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research context

This review investigated studies that examined the experiences of nursing home staff engaged in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. The nursing home settings could be from any country, cultural context, or geographical location.

Types of studies

Different types of qualitative studies were examined in this review, such as phenomenological design, focus groups, and grounded theory. Mixed methods studies were included only if qualitative data could be extracted from them.

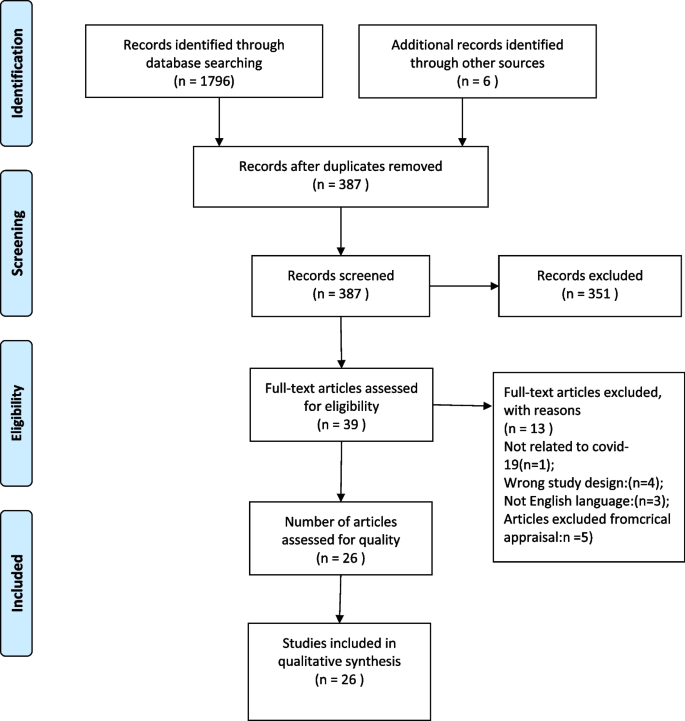

The initial search comprises 1,802 publications imported into Endnote X20 software. The Endnote function and Endnote recognised 1415 duplicates from the hand search, leaving 387 papers for evaluation based on title and abstract correlation. We retrieved the full text of 39 articles that met the selection criteria for further assessment, and 26 of them met the quality assessment criteria. Figure 1 and Appendix S2 provide additional details. Two reviewers (YXF and XSH) independently carried out the screening process, and no disagreements occurred.

The JBI Tools for Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-QARI) was used to assess the rigor of each paper's research technique [37]. A cutoff point of six out of ten'yes' answers was used to ensure exclude lower quality studies [38]. The score distribution of the included studies ranged from 7 to 10. Disagreements between the two reviewers (YXF and XSH) were discussed and resolved with a third reviewer. A quality rating of the inclusion studies is provided in Table 1.

JBI-QARI Data Extraction Tools was used as a data extraction tool, which has been verified to have good reliability and validity [60]. The relevant results were extracted and calculated by re-reading the selected article, including research characteristics, participant demographics, and descriptions of any interesting results. XSH was in charge of research selection and data extraction, while YXF was responsible for data extraction. Each article was critically examined for methodological coherence using the criteria defined in the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.

We used the JBI meta-aggregation approach for synthesis, which consists of the following five steps [37]. Step 1-Data extraction: Extract relevant data from the included studies, such as study information, participant characteristics, and research findings. Step 2-Preliminary coding: use the information that was obtained to generate preliminary codes and topics. Step 3-Classification: classify and classify the preliminary encoded data to create a more general theme and category. Step 4-Thematic synthesis: We used Thomas and Harden's [61] three-stage approach to thematic synthesis: (1) coding the text, (2) constructing descriptive themes, and (3) generating analytical themes. Using these methods, an overarching narrative was built from the contained literature, and new primary themes were identified and interpreted. Two researchers (YXF and XSH) conducted the original coding procedure, while another researcher (PWS) generated the descriptive and analytical themes. Finally, the whole study team discussed and agreed on the consistency and adequacy of the theme interpretations [61]. Step 5-Narrative synthesis: represent the synthesized data in a narrative format to reach a clear study conclusion. We must state that no theoretical framework or model has been used to guide the data analysis in the whole step. Please see the author's contribution statement to see specific division of work.

Two reviewers (YXF and XSH) independently evaluated each finding and assigned a credibility rating to each finding. The credibility levels are as follows [32]: Clear (U) — relates to findings beyond a reasonable doubt; Credible (C) — relates to findings that are interpretations, plausible in light of the data and theoretical framework; Not supported (Un) — when the findings are unsupported by the data. There is no disagreement at the level of credibility. We categorize the findings into different categories based on the similarity of their meanings; then, these categories undergo meta-synthesis, generating synthesized findings through meta-aggregation [62]. The first author (YXF) led the meta-synthesis process. When reviewing findings/categories/synthesized findings, this process is repeated. If there are any doubts, we will consult the original literature and hold group discussions to reach a consensus. We use the ConQual tool to assess the credibility of the synthesis results [63].

This review encompasses 26 original studies, comprising 22 qualitative studies and 4 mixed-methods studies. Figure 1 presents a detailed step-by-step account of the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the works. In the evaluation of 26 studies, quality scores ranged from 7 to 10. Furthermore, four studies gained a score of 7, four scored 8, 11 scored 9, and 7 achieved a score of 10, which is shown in Table 1. The included studies were published from 2020 to 2024 and involved 906 nursing home staff across 16 countries globally. Table 2 presents detailed information of all included studies.

We extracted 267 original findings from 26 papers (Appendix S3): 263 unequivocal and 4 credible. We categorized the 267 original findings into 15 categories based on their similarity in meaning across various categories. The information from these categories has been put together into three compiled findings: challenges, coping strategies and recommendations for future preparedness (see Table 3).

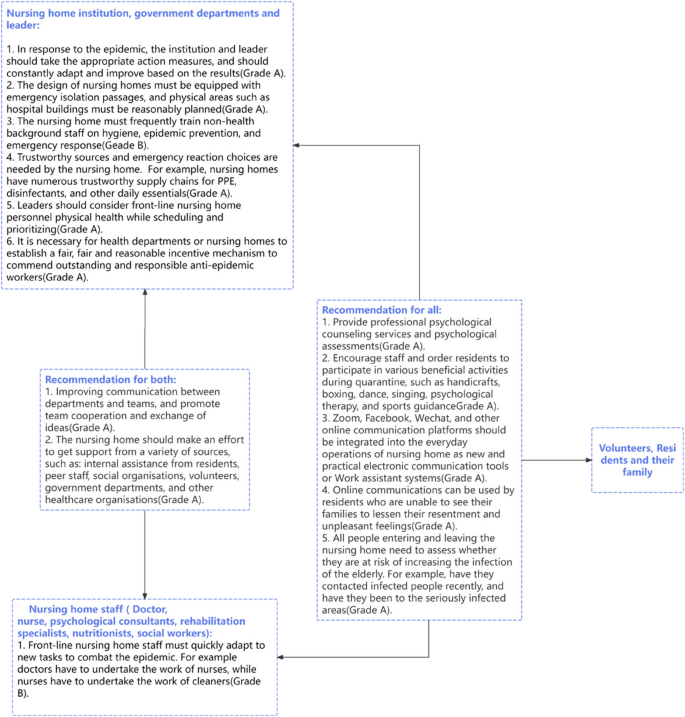

Based on the above ConQual approach tools [52] and 267 original findings from the inclusion studies, synthesized findings 1 were rated as low level, while synthesized findings 2 and 3 were rated as moderate level. The ConQual summary of results is displayed in Fig. 2.

The three synthesis findings of this study were obtained from 15 categories. This synthesis finding 1—Challenge (based on 150 original findings), delineates the obstacles encountered by nursing home personnel in addressing COVID-19. Synthesis finding 2—Coping Strategies (based on 102 original findings): This section discusses the measures enacted to resolve the difficulties mentioned in synthesis finding one. Synthesis finding 3—Recommendations for Future Preparedness (based on 15 original findings): Staff integrate their anti-epidemic experiences, encompassing problems faced and solutions utilized, to determine essential modifications for improving the nursing home's crisis response efficacy.

Synthesized finding 1: challenges

This chanllenges comes from 150 original findings, which can be further divided into six groups: challenges in implementing epidemic prevention and control, materials shortage, negative emotions, inadequate departmental communication and coordination, lack of support (14 extracted findings), and physical strain.

Due to the special nature of COVID-19, some new and complex measures are needed to treat and prevent infection, but the staff and residents of elderly care institutions have different perceptions of these measures:

It was what I do not think we all expected. It was something new. We had no experience... There were new changes every day, and there were new orders that we had to follow every day.

(Hoedl, Thonhofer et al., 2022. P2499)

No one thought that this was coming, it caught everyone flat footed without any adequate preparations and strategies to deal with a pandemic” —Female mental health nurse.

(Nyashanu, et al. 2020 et al., 20)

The lack of human resources and materials were also another challenge:

We had a lot of staff who were sick. We worked understaffed. We worked for two months under-staffed without adequate replacements. It was painful and very tiring. We were very tired.

(Kaelen, van den Boogaard et al., 2024. P11)

We now have enough tests, but cannot test all staff because we would go from critical staff shortage to [an] untenable staff shortage...

(White, Wetle et al., 2021. P2)

During COVID-19, nursing home staff and residents experienced negative emotions caused by social contact, work pressure, and fear of infection:

Personal stress is an issue….my management of my stress was going to the gym and just winding down, but of course that can’t happen…I’ve talked to managers and deputy managers from other homes and it’s pretty similar, the stress doesn’t stop.

(Hanna, Giebel et al., 2022. P6)

I blame myself for every death. I didn’t turn them away...

(Marshall, Gordon et al., 2021. P4)

Staff is anxious, scared, mean, and unprofessional...

(Miller, Fields et al., 2021)

Poor communication between different departments also posed an obstacle to the smooth implementation of epidemic prevention work:

It confuses us, it’s difficult for us to follow all the guidelines, especially as a social worker, the guidelines change so very often. Before I can implement a procedure, I get another procedure instead. It confuses us, it confuses the employees, it confuses the families, it confuses the patients who do not know what’s happening. Yesterday it was that way, why is it this way today.

(Lev, et al., 2024)

The nursing home staff faced a shortage of both internal and external support, including support and understanding from residents, their families, managers, government departments, and health departments:

To be honest, the politicians have sacrificed us. We will totally burnout and the elderly will die due to COVID-19. We are worth nothing to them!

(Leskovic, Erjavec et al., 2020. P668)

...On the day of the outbreak... no one told me what to do with the residents when they got sick...

(Lev and Dolberg, 2024. P10)

... So, we just started fighting for our workplace to take us back, right? By force... (P14)

...They, the Ministry of Health, only add [tasks]. They themselves do not know what’s going on...(P14)

...If we do not do what we know, or what we need to do, no one will help us. No one supports us, let’s call it by its name... (P14)

(Lev and Dolberg, 2024)

Physiological effects were also concerning. Most front-line nursing home workers said long hours and heavy workloads lead to fatigue and burnout:

...If I work eleven hours, I'm dead in the evening...

...You go home, you take a shower, you sleep, you go back to work. And the fifth day is still okay, and from the sixth day on you just function, I think...

(Hanna, Giebel et al., 2022. P2500)

...I must work 16 hours on the weekends, and I wear a mask all the time. and I have a headache most of my shift!... I feel so drain[ed] when I get off work...

(White, Wetle et al., 2021. P3)

Synthesized finding 2: coping strategies

Despite facing hurdles in the fight against COVID-19, nursing home staff have developed coping mechanisms, providing valuable experience for staff in various positions. This synthesized finding is based on 102 original findings and is divided into six categories, which include role adaptation and redefinition, innovative solutions and technology, work organisation and cooperation, positive psychological service, seeking support from the community and relevant departments, improving infection prevention awareness.

To prevent the spread of COVID-19, nursing homes have implemented closed management measures. The staff's job role has expanded beyond its original limits, requiring them to accept additional jobs and roles:

...we are busy with the staff and [giving] therapy for the staff, and it’s dealing with other things that we haven’t dealt with before.

(Leskovic et al., 2020. P13)

The use of electronic communication channels and technological tools can address the issue of inadequate communication among different populations and help reduce negative emotions.

A nursing home manager stated that providing internet visits during restricted management can foster trust between the facility and the families of residents:

...Versus now it’s basically through the little Zoom visit… the family has to be able to have that trust in us...

(Hendricksen et al., 2022.)

On the other hand, video conferences between different teams in institutions can reduce the risk of personnel gathering and promote organisational communication:

... We have a group and we text, all kinds of links... we had also Zoom meetings... to check what’s up, what’s going on.

(Lev and Dolberg, 2024. P11)

Most studies have confirmed the necessity of teamwork, including professional departments, institution managers, doctors, nurses, residents and their families, external volunteers and social workers. The timely recognition and praise of the work by the managers have enhanced the determination of the entire elderly care institution to overcome difficulties:

In the meantime, the nursing home's manager came to the handover and praised us for our performance. In times of crisis, people stick together.

(Hoedl, Thonhofer et al., 2022. P2501)

On the other hand, when the members of each team work together in unity, there is more perseverance to overcome challenges:

... Why? Because we depend on each other and help each other, and because our enemy was external... Coronavirus and incapable and corrupt Politicians.

(Leskovic, Erjavec et al., 2020. P669)

Emotional support and activities for residents and staff to help manage stress and fear caused by unexpected epidemic:

Mental health support from supervisors and frequent breaks when at home.

(Miller, Fields et al., 2021)

Considering that these elders had been isolated for more than 40 days, we also used many ways to give them some psychological comfort...

(Yang, Li et al., 2021. P8)

Can mobilize all available resources and to some extent solve the shortage of human and material resources. An employee of a nursing home said that the help of third-party institutions has eased the pressure of their nucleic acid testing:

...they’ve been brilliant the hospice. And they’re still fighting… and they’re fighting for us as well to get the testing, for all the staff and the residents on a regular basis...

(Marshall, Gordon et al., 2021. P7)

The organisational framework and medical proficiency of nursing homes are weaker to those of hospitals; thus, it is essential to enhance the epidemic prevention awareness of non-medical workers and all residents during the pandemic response.

...After the training, the elderly improved their consciousness, and then the disinfection and isolation were standard. Our colleagues would pass some better news information about COVID-19 to their old people every day when they went to work, and then they would teach the elderly learns some knowledge about the prevention of virus and guide them to do well in self-protection...

(Yang et al., 2021. P8)

Synthesized findings3: Suggestions for future preparedness

This synthesized finding is based on 11 original findings, grouped into three categories: Enhancing communication and decision-making in response to COVID-19 changes, optimizing material supply channels and physical space, increasing medical related team and training.

A nurse in an elderly care institution thinks that family visits should be allowed when facing a crisis similar to COVID-19 in the future:

...Among colleagues it was said that contact with the family was capital. In the future we must really think about this because contact with the family is very important.

(Kaelen, et al., 2024, P13)

Several therapists in nursing homes suggest that institutions should change the current system and promptly attend to new information:

...I think that (pay attention to COVID-19) was the main thing because you cannot make the protocol and publish it in the afternoon and at 10 a.m. the next day send me another protocol because, of course, that in the end is a waste of time and resources in itself...

(Chimento-Díaz, et al., 2022.)

Multiple and reliable supply paths for materials, along with suitable physical environments, promote the high-quality development of future nursing homes. A nursing home management stated that [32] when the outbreak emerged, the government requisitioned certain goods, preventing their institution from acquiring sufficient supplies. He asserts that [32]: a competent nursing home administrator must be equipped with sufficient resources at the onset of an outbreak. A study [57] from China suggests that the current setting of nursing homes is unreasonable, and suggests that in the future, the design of elderly care institutions should increase isolation channels and isolation wards.

…We had to create infection areas and quarantine areas…

(Sander, et al., 2023)

It is essential to add medical teams and training in future nursing homes when facing public health crises, as this will not only improve the institution's emergency response efficacy but also equip employees with the requisite skills and knowledge for protecting residents' health and mitigate the effects of crises on elderly facilities.

...The organisation should have medical staff, only nursing assistants and managers are not enough, they do not have enough professional knowledge to face public health events such as epidemic...

(Yang, Li et al., 2021. P9)

“Adequate funding(support to train) so that we can actually provide the care that these poor people need, not just during COVID.

(Savage, Young et al., 2022. P05)

We conducted a qualitative meta-synthesis of 22 qualitative studies and 4 mixed studies reporting qualitative findings to reveal the challenges, coping strategies and suggestions for future preparedness encountered by nursing home staff in fighting the COVID-19 epidemic. The qualitative synthesis review revealed that the nursing home staff, primarily consisting of doctors, nurses, nursing assistants, psychological consultants, rehabilitation specialists, nutritionists, social workers, managers, and some government officials, faced multiple challenges. There are three main aspects of challenges faced by nursing home staff: self-factors, epidemic factors, and institutional residents and their families. Based on the original findings of included studies, the challenges of the nursing home staff during the COVID-19 epidemic were classified into six categories.

The most significant challenge faced by nursing home staff is negative emotions (21/26). Among the 26 studies included in this review, 21 mentioned negative emotions, such as stress, frustration, irritability, anger, anxiety, depression, fear, etc. The sources of these negative emotions are mainly threefold: self-factors, epidemic factors, and institutional residents and their families. More details are shown in Appendix S4. This is consistent with the findings of many previous quantitative studies. A recent study from nursing homes in Spain spanning 21 years has revealed significant depressive symptoms among staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. These symptoms were found to be significantly negatively correlated with psychological resilience, personal achievement, and satisfaction, while they were positively correlated with emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and experiential avoidance [64]. The difficult decisions regarding virus containment faced by nursing home staff, as well as the deaths of residents they live and work closely with, are sources of their anxiety and depression [64]. Outbreaks occurring in high-density living facilities such as nursing homes can lead to prolonged outbreaks, resulting in a high number of deaths, which also exacerbates the fear among nursing home staff [65]. As mentioned above: Comorbidities and aging among the elderly in nursing homes increase the risk of infection and the difficulty of treatment. This extraordinary circumstance put nursing home personnel at significant risk of experiencing stress, anxiety, and depression [58, 66]. Another study from Spain indicated that the professionals who had direct contact with patients affected by COVID-19 had increased stress levels and decreased quality of life [67].

Another important challenge is the implementation of epidemic prevention and control measures (18/26). Because COVID-19 has a long incubation period, is highly contagious, can transform into many different types (Alpha, Delta, Omicron, etc.), and has a complex immune response, it requires evolving approaches to treatment and prevention [68]. Front-line teams in nursing homes will formulate prevention and control measures under the direction of professional physicians, adhering to WHO and professional association guidelines and consensus [69, 70]. These measures will mainly include hygiene and infection control, personnel management and health monitoring, visit management, and psychological support [52, 59]. The formulation of evidence-based preventive strategies has been impeded by insufficient epidemiological insights into the novel pathogen [43], compounded by low compliance rates stemming from inadequate community engagement during intervention deployment [57, 59].

The third category of challenges is related to lack of resources (14/26), including shortages of materials, manpower, particularly during the early stages of COVID-19, and PPE (masks, goggles, and protective clothing) [71, 72]. On the other hand, many nursing homes are staffed mainly by assistant nurses, and often have few professional health care personnel, such as nurses, doctors, rehabilitation specialists, and nutritionists [73]. Furthermore, some nursing homes lacked their own medical team and rely on the nearby hospitals [59]. Due to the lack of a reliable material supply chain, some institutions must rely on their own manual production or seek help from social institutions after the original material supply chain was broken [32]. The aforementioned circumstances have forced some nursing homes to rely on external assistance to address the COVID-19 situation.

Lack of support (8/26) is another challenge that cannot be ignored (8/26). The nursing home staff in our review expressed that they needed support from the ministry of health, families, leaders, and residents. Although nursing homes had a harder time coping with the epidemic than hospitals, public attention and support were frequently directed toward hospitals [74]. As mentioned earlier, not all nursing homes possess adequate medical personnel, and those lacking sufficient professional doctors and nurses must rely on assistance from the government and professional medical institutes [73]. The Ministry of Health's role is not limited to providing financial support. Policymakers can formulate relevant policies and regulations to standardize the service standards, staffing, and facility requirements of nursing homes, improve the level of industry standardization and safeguarding the legitimate rights and interests of the older people [75]. Conversely, to prevent the transmission of infection, the nursing home staff have limited the way and frequency of interactions between senior individuals and their families, as well as among older residents on other floors or in separate rooms [17, 53]. Some older people and their families have expressed they are unable to accept this.

In addition, the nursing home staff faced another two challenges during the epidemic: physical strain (6/26) and inadequate departmental communication and coordination (6/26). This study identifies six studies that show significant physical strain on nursing home staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. This strain includes physical exhaustion, fatigue, burnout, and excessive workload. These issues are primarily related to their roles and responsibilities, concerns for resident and staff safety, and substantial workload demands [53, 56]. Many staff had to work for a long time for fear of wasting PPE [48]. Moreover, sustained work pressure and infection anxiety can lead to physical and psychological fatigue [33]. This review presents six studies that highlight the challenges of inadequate communication and coordination among multiple departments in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Effective communication plays a crucial role in ensuring the safety and well-being of both workers and residents during the COVID-19 pandemic [76]. Lack of cooperation between departments led to poor information communication and low work efficiency [33]. However, the nursing home staff in this review have stated that a significant challenge is inadequate communication among many agencies and departments, resulting in uncertainty and inconsistency in guidance, which increased stress levels for the staff [52].

The most important coping strategies in our review emphasizes that work organisation and cooperation (12/26) are crucial for the efficient use of organisational resources, employee satisfaction, leadership development, and the social participation of residents in nursing homes and other medical institutions. In this study, “Work Organisation and Cooperation” primarily focuses on the team and organisational levels. This includes collaboration and communication among team members, support from management, and the use of external resources; for more details, refer to Table 3 and Appendix S4. Related studies have shown that collaborative work not only enhances job satisfaction but also strengthens organisational adaptability and resilience, and has a positive emotional impact on nursing managers and employees [77, 78]. Zhao et al. identified that support from management is the primary coping strategy used by registered nurses [59]. The included studies in our review demonstrated that team collaboration is comprehensive, and timely, effective communication of information and empathy among nurses, doctors, managers, and government officials can facilitate epidemic management and address complex issues in nursing homes [48, 52, 56].

Moreover, nursing homes need the support of communities and organisations (11/26) to enhance their ability to respond to pandemics. This may include collaboration with public health departments, local governments and other long-term care facilities [52, 79]. Support can also come from volunteers, community members and non-governmental organisations, who can provide additional human resources, material supplies, and other necessary resources [34, 48]. For example, policies in some countries/regions support staffing capacity and increase wages to promote the service of individuals in nursing roles [59]. In addition, leadership and flexible decision-making can promote medical teams to effectively combat the epidemic [43, 80].

Innovative solutions and technology (10/26) play a crucial role in the prevention and control of COVID-19 in nursing homes. An interesting phenomenon was that the application of new technologies, such as email, Zoom, Facebook, WeChat, and other electronic communication systems or medical electronic auxiliary systems, would make work convenient during the special phase [48, 51]. The use of these technologies reduces the frequency of home care visits and guarantees timely medication adherence by patients. New-generation information technologies, represented by big data and artificial intelligence, serve as important foundational supports and are widely applied in the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and management of COVID-19 [81]. These applications include personal tracking, monitoring and warning, virus source tracking, drug screening, medical treatment, resource allocation, and production recovery [81]. Research has shown that providing communication services to residents or employees and their relatives through technology such as telephone and internet can alleviate anxiety and fear [82].

This review identifies positive psychological service (8/26) as the fourth key strategy for the effective prevention and management of COVID-19 in nursing homes. Social isolation significantly elevates the risk of cognitive decline, anxiety, and depression among residents and staff during COVID-19 [59]. In the study by Kaelen et al., individuals exhibited heightened levels of anger, tension, despair, and discomfort, resulting in decreased optimism and interest in life [45]. COVID-19 restrictions have led to significant changes in participants’ work and daily lives, culminating in anxiety and loneliness, as corroborated by other investigations [17, 59]. Psychological support and social services, emotional support, and activities for residents and front-line staff are essential [83]. Another study suggests that providing cultural and entertainment services such as television, radio, and reading can guide the development of beneficial interests and hobbies among the elderly, enrich their spiritual and cultural life and help them understand and cope with psychological pressure during the epidemic [84]. Conditional nursing homes assess the psychological status of elderly resident and staff, identify those at higher risk of psychological problems, and coordinate with professionals to provide psychological intervention [57, 59]. To sum up, the positive psychological services can not only help improve the mental health of residents, but also enhance their ability to cope with the epidemic and reduce the risk of loneliness and depression, thereby improving their overall quality of life.

To effectively prevent and manage the spread of COVID-19 in nursing homes, most institutions have implemented two additional strategies: role adaptation and redefinition (5/26), and improving infection prevention awareness (9/26). During the pandemic, the nursing home staff may need to adapt to new roles and responsibilities to cope with staff shortages and increased workload [41]. This may include reallocating tasks, increasing multi-skill training, and collaborating across departments when necessary [59]. A study showed that the workload has changed significantly compared to before; for example, the access channel needs to be monitored, and nucleic acid needs to be monitored daily [59]. Some employees may require supplementary training to deliver remote information and assistance to family members and former carers, as well as to facilitate communication with hospitals to ensure compliance with mandated transfer care agreements [70]. In order to prevent the spread of COVID-19, nursing homes have to implement infection control and prevention preparedness [69]. This includes extensive testing, isolation and resident grouping, employee protection and support, promotion of residents'well-being, and technological innovation [59]. Extensive testing can help identify asymptomatic cases and quickly implement infection control procedures [42]. In addition, isolation and grouping strategies can divide residents into different groups based on their COVID-19 status to reduce the risk of virus transmission [53].

In this review, the nursing home staff stated that drawing upon past experiences enables nursing homes to develop comprehensive recommendations to deal with potential future pandemic crises. The nursing home staff encountered numerous problems throughout COVID-19; however, they implemented effective coping strategies, such as communication and decision-making, systematic and organisational changes, resource allocation, and management, to achieve temporary success.

This review considers communication and decision-making (5/26) as beneficial suggestions for future responses to public health emergencies in nursing homes. In the decision-making process, the management of nursing homes needs to consider the wishes and needs of residents and staff. Home visits should not be cancelled abruptly and completely but should be replaced with online visits [26]. On the other hand, effective communication is key to ensure that residents, family members and the outside world understand the true situation in nursing homes and provide assistance when necessary [42]. In addition, professional nursing homes should have a crisis task force composed of members from different professional backgrounds, which can ensure that problems are considered from multiple perspectives and comprehensive response strategies are formulated [52].

The second suggestion for nursing homes is to prepare for future public health crises by Optimizing material supply channels and physical space (5/26). Nursing homes will need to amend their unreasonable rules in the future to fully cope with future public health crises [59]. Some staff pointed out that the physical space design of nursing homes lacked a humanistic atmosphere and was excessively cramped [57]. Consequently, the nursing home staff in this study suggest that nursing homes have to consider the design of their physical environment to successfully manage infections throughout the pandemic [17, 53].The optimization of physical space includes providing effective ventilation systems, establishing isolation areas, and designing one-way flow paths to reduce the risk of cross-infection [17]. Institutions with irrational physical spaces can adjust their existing structures to cope with emergencies. For example, this may include converting public areas into isolation zones, rearranging beds to maintain social distancing, and reorganizing recreational areas to minimize unnecessary movement between different zones [52]. In summary, our team believes that the design of future nursing homes should fully consider the rationality of their architecture and spatial structure from a medical perspective.

The final suggestion for nursing homes to prepare for future public health crises is to increasing medical related team and training (4/26). Our findings indicate that, post-COVID-19 pandemic, nursing homes must augment their emergency response protocols to better prepare for future public health crises. This may include upgrading emergency plans, infection control, staff training, and resident and employee health monitoring systems [47]. Furthermore, our review highlights the need to optimize nursing home staffing structures. The number of doctors and nurses needed to be increased [85]. It was suggested that the nursing homes should be equipped with rehabilitation therapists and nutritionists [85, 86]. As the primary staff members who have the most direct contact with residents, the carers in nursing homes should regularly receive relevant training. Research shows that they often lack knowledge and skills, which training can effectively fill [85]. Nursing homes must adjust to the new normal as epidemic limitations are lifted. This may include gradually resuming family visits, adjusting activity arrangements, maintaining social distance, and monitoring and responding to possible resurgences [52].

A meta-synthesis is a reinterpretation conducted by others with advantages and disadvantages. To the best of our knowledge, this review appears to be the first contribution in these areas. The use of rigorous qualitative investigations ensures a comprehensive yet targeted data collection. The study included in the summary isn't limited to the year of publication to guarantee sufficient literature.

This study acknowledges several biases and limitations that may influence the broad applicability and interpretation of the research findings. Firstly, the sample exclusively comes from elderly care institutions, revealing selection bias due to the lack of data from the African region. This limitation restricts the global representativeness of the sample and, consequently, the generalizability of the results. Secondly, information bias arises from our reliance on textual descriptions for data collection and measurement. Inconsistencies in cultural background and interview outlines may introduce inaccuracies and inconsistencies in the data, thereby affecting the reliability of the findings. Thirdly, the research design limitations stem from the inclusion of primarily qualitative studies, which do not allow for the strict control of variables as seen in quantitative research. The subjective nature of qualitative data may introduce additional biases, necessitating cautious interpretation of the results. Fourthly, language barriers are a concern, as the study only included publications in English and Chinese, potentially excluding valuable research in other languages and limiting the diversity and global applicability of the findings. Fifth, the lack of input from care recipients or their families presents a gap, as the evidence is predominantly based on the perspectives of staff working in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic without incorporating the views of residents or their families. This omission may restrict the comprehensiveness of the results, particularly regarding population and environmental aspects. Finally, the results only apply to nursing homes, as all studies were done there. The findings may not be transferable to other types of care institutions, such as children’s welfare homes, or community-based care settings like community day care.

Despite these limitations, the study’s findings offer valuable insights and guidance for nursing home staff during unexpected situations, such as pandemics, and can inform measures to enhance the efficiency of future public health emergency responses. Future research should aim to expand the sample size, enhance sample diversity and representativeness, and improve the broad applicability of the findings.

The review's recommendations for practice are listed in Fig. 2 and have been given a grade of recommendation in accordance with JBI [87]. Grade A is a strong endorsement, while grade B is a less powerful endorsement. Below are some suggestions for further reading. To strengthen the effectiveness of the experience of the nursing home staff and provide recommendation for their training in future. It is suggested to optimize the nursing homes from the aspects of implementation characteristics, internal and external environment, individual characteristics of personnel and implementation process based on the experience of all over the world, to improve their ability to respond to public health emergency events.

The meta-synthesis aims to provide comprehensive qualitative evidence from nursing homes to guide the management and prevention of public health emergencies such as COVID-19. Three synthesis findings identified in the systematic review are the challenges and coping strategies faced by nursing home staff during COVID-19 and suggestions for the future.

The findings of this study call for policymakers and healthcare leaders to take a series of actions to better address potential health crises in the future. Ensure resource availability: Ensure a reliable supply chain for basic materials, including personal protective equipment, and adequate staffing levels, with a focus on professional medical personnel. Optimise physical space: Redesign the layout of the sanatorium, including effective ventilation, isolation areas, and one-way flow paths to minimise the risk of cross-infection. Increase training and staffing: Strengthen personnel training in emergency response and infection control and increase the number of medical professionals in nursing homes. Encourage interdisciplinary collaboration, develop overall strategies, and address the social, economic, and psychological aspects of public health emergencies. Prepare for future crises: Develop and update emergency response plans, infection control protocols, and health monitoring systems to better prepare for future public health crises. And we also suggested that future research focus on the differences in nursing homes of different backgrounds (such as public and private, high-income and low-income areas).

The limitations of this study suggest that future research teams should focus on the following: incorporating data from a wider range of regions, including under-represented areas such a Africa, to enhance global representation. Incorporate research published in various languages to gain broader insights and experiences. Explore different nursing environments: study the experiences and strategies of other types of nursing institutions, such as child welfare homes and community nursing environments, to identify transferrable lessons learnt. Conduct longitudinal research to track the long-term impact of the epidemic on nursing home staff and residents and assess the effectiveness of implementation strategies over time.

The synthesis can help identify the factors that influence effective epidemic control. In addition, further research is needed to explore how to optimize the staffing and physical layout of nursing homes to improve their ability to cope with public emergencies.

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease

- WHO:

-

World Health organisation

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- PPE:

-

Personal protective equipment

- JBI-QARI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument

We thanks for all participants and funding grants.

This work was supported by the Shenzhen People's Meaning Nursing Fund for Young and middle-aged people [grant numbers: SYHL2022-N009]; the Research Project on Nursing Innovation and Development of Guangdong Nursing Society in 2023 [grant number: YIYM2023009]; Medical Foundation of Guangdong Province [grant number: A2024009].

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

All participants in the study have been appropriately ranked according to the tasks undertaken. The funding grants given to support this study are listed and consent was obtained from the fund owners. Therefore, there is no conflict with the owners of the funds listed herein. The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Yang, Xf., Guo, Jy., Peng, Ws. et al. Global perspectives on challenges, coping strategies, and future preparedness of nursing home staff during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res 25, 872 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-025-12926-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-025-12926-z