BMC Health Services Research volume 25, Article number: 933 (2025) Cite this article

Hospitals constitute an essential part of health systems. Although fragmented data indicate that hospitals in many European countries face financial problems, no structured, comparative data are available. The objective of this study was to identify, synthetize, and map the existing evidence on hospital financial performance (FP) across European countries.

A scoping literature review was conducted, following standardized methodological guidelines and a previously published protocol. Four scientific databases (PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, and ProQuest Central) were searched to identify studies published since 2010. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the focus is on hospital settings in a European country; (2) FP is measured at the hospital level using a defined ratio; and (3) it is a full text publication in English.

After screening 3422 records, a total of 62 full text publications focusing on 13 European countries were included (53 empirical studies and nine policy/discussion papers or technical reports). The empirical studies focused on four main categories: (1) measuring and/or comparing hospital FP (n = 20/53); (2) identifying associations between FP and other hospital (mostly organizational) characteristics (n = 38/53); (3) analysing the impact of an event on hospital FP (n = 11/53); and (4) other, e.g. developing a comprehensive hospital performance matrix with FP as one of the dimensions (n = 6/53). The vast majority of empirical studies are quantitative, use secondary data sources, and apply single profitability indicators to measure FP. The results of the identified studies are often mixed and highly specific to context, data, and methods.

Research evidence on hospital FP in Europe is available for a limited number of countries. The existing empirical studies focus mostly on analysing the relationships between hospital FP and other organizational characteristics (e.g., ownership and management style). Our review highlights two major research gaps: (1) a lack of evidence on associations between hospital FP and quality of care metrics; and (2) a need for more theoretical/conceptual work on composite FP metrics that are relevant for hospital care providers.

Hospitals constitute an essential part of health systems. Their primary function is the provision of health care services; however, they can also play an important role as centers for research and education, as well as support units for various community outreach and care coordination initiatives [1]. Hospitals are the cornerstone of national emergency preparedness plans— for example, those applied during the COVID pandemic [2, 3]. In Europe, hospitals account for more than one-third of total current health expenditures (CHEs) (in 2022, the average share of hospital expenditures in total CHEs across the European Union (EU-27) was 36.4%, whereas among 34 individual European countries for which data are available, the value ranged from 26.9% in Germany to more than 50% in Cyprus and Croatia) (Supplementary File 1). The strong position of hospitals underlines the importance of their financial sustainability for the health service provision security and overall health system performance.

However, the concept of hospital financial sustainability is complex and multidimensional. There are numerous economic theories that were applied to analyse the relationships between hospital FP and other variables [4]. These include, for example, the economic model of hospital behaviour by Newhouse (1970) [5] and Hoerger (1991) [6] which emphasize the non-for-profit hospital objectives to maximize outputs and quality of care over profits; the institutional theory by Dimaggio and Powell (1983) [7], which indicates that a variety of external factors can impact hospital decisions (e.g., whether to partner with other organisations and how to address financial challenges); and the resource-dependence theory by Pfeffer & Salancik 1978 [8], which emphasizes that hospital focus on securing adequate resources (including financial ones), especially in competing markets.

There is also a significant body of empirical literature that has focused on hospitals’ financial performance (FP), including: (i) measurement techniques [9, 10], (ii) determining factors [11,12,13], and (iii) its association with diverse hospital performance metrics [4, 14]. However, the vast majority of empirical work seems to be based on the United States (US) market. Hospital FP can be measured via a variety of individual metrics (e.g., standard sets of indicators in factor analysis based on financial statements), as well as composite measures (i.e., combining multiple metrics). Research evidence points towards the advantages of the latter approach [10, 15]. Several literature reviews of empirical studies [11,12,13] have indicated that, in the US, a variety of factors— such as hospital size and business model, localization, affiliation, payer mix or market concentration—can impact hospital financial standing. Similarly, in research focused on analysing the association between hospital FP and other hospital performance metrics, including i.a. quality of care, technological advancements, and patient satisfaction, a significant portion of the evidence also comes from the US [4, 14].

In Europe, as in other parts of the world, hospitals can operate under diverse governance frameworks related, i.e., to: ownership (public vs. private); sources of funding (e.g., government budget vs. public or private insurance vs. out-of-pocket payments); business models (for-profit vs. not-for profit); and legal form (e.g. corporations, trusts, foundations, or unique organizational forms dedicated solely to health care providers) [16]. However, in the majority of European countries, public hospital care provision prevails in terms of both ownership and funding sources [17]. In 2022, among the 26 European countries for which data are available, only three cases (Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands) had a share of publicly owned hospital beds below 50%; whereas in 18 countries it was above 70% (Supplementary File 1). In the same year, the EU-27 average share of ‘government and compulsory contributory health financing schemes’ in total hospital funding was 93.4%, whereas among 33 individual European countries for which data are available, the share of public spending in total hospital expenditure ranged from 69.1% in Greece to 99.5% in Iceland and was above 90% in 23 countries (Supplementary File 1). Public hospitals operate in extremely complex, heavily regulated environment and are characterized by high resistance to change [17]. From the financial performance perspective, public hospitals often hold the statute of ‘public service providers’, which may drive an obligation to provide services regardless of their ability to cover production costs [18]. In practical terms, some legal forms of public hospitals may not be subject to financial bankruptcy procedures [19]. They often operate under soft budget constraints and are expected to receive additional financial support (bailouts) when hospital closure is not a politically viable option [20].

Numerous studies indicate that hospitals across Europe are struggling with persistent financial deficits and/or insolvency problems. For example, in several Central and Eastern European countries, public hospitals continue to accumulate debts, whereas governments attempt to address this issue through bailout and restructuring programs, which are often ineffective [21,22,23,24,25,26]. In Croatia, Hungary and Poland, public hospitals systematically accumulate overdue liabilities (arrears), mostly for pharmaceutical and medical products [24, 26]. In Hungary, aggregated hospital arrears reached a peak of HUF 117 billion (€ 300 million) in March 2024, with hospital managers pointing toward their limited capacity for debt management due to insufficient financing [26]. In both Croatia and Poland, external analyses conducted by World Bank experts have indicated that the main drivers behind public hospitals’ persistent insolvency issues are complex, and include a mix of both macro- and micro-level factors. At the system level, both countries are characterized by overcapacity in hospital care with simultaneous weak governance structures and ineffective financial mechanisms. At the individual hospital level, there is a problem of limited management accountability and a lack of staff cost control [24, 27]. Available fragmented data (mostly in the form of short press-releases, and/or policy notes) indicate that the problem also exists in other European countries. For example:

No comparative analysis of hospital FP focused specifically on Europe has been identified. Thus, following the general objectives of scoping reviews [33], we aimed to identify, synthetize, and map the existing evidence on hospital FP across European countries. Our objective was to answer the following research questions: (i) When/where/what research was conducted?; (ii) How was hospital financial performance measured?; (ii) What is the evidence on associations between European hospitals’ FP and other variables? Our results contribute to building a knowledge base on the topic and provide meaningful implications for both health policy and future studies.

Our review followed standardized methodological guidelines [34, 35] and involved six steps: (i) defining the research question, (ii) literature identification, (iii) studies’ selection, (iv) data extraction, (v) collating and reporting the results, and (vi) consultation and engagement of knowledge users. The project was registered via the Open Science Framework [36], and its protocol was published in a peer-reviewed journal [37].

Five specific review questions were formulated: (i) What types of studies are available?, (ii) What is the main focus of the available publications?, (iii) How was hospital FP measured?, (iv) What were the results?, (v) What limitations were stated?

In April 2025, four scientific databases were searched: Medline via PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, and ProQuest Central. The search strategy combined terms from three topics: (i) hospital AND (ii) financial performance AND (iii) European country (Table 1). The geographical scope covered 40 European countries (only 4 small countries with populations less than 40 000 inhabitants were excluded from the keywords list). Terms were searched as keywords in title and/or abstract, with a publication date limit from 2010. Supplementary File 2 presents the full search details. An additional Google Engine search was also conducted, and the reference lists of relevant papers were manually scanned to identify further studies.

Mendeley was used to remove duplicate records, and Rayyan was employed for the studies selection process. The latter consisted of two stages: title and abstract screening, followed by full-text screening. In both stages, two researchers participated, applying the following procedure: (i) a random 10% sample of records was screened independently by both researchers; (ii) the results were then compared and discussed; (iii) agreement between them was high (above 80% raw agreement), and the remaining records were screened by one researcher. Full text publications were assessed on the basis of the following inclusion criteria: (i) the focus was on hospital settings in a European country; (ii) FP was measured at the hospital level (studies focusing solely on financial profits/losses from a single service were excluded); (iii) FP was measured using a defined ratio, not solely proxy measures such as revenues or cost values alone; (iv) the publication was a full-text peer-reviewed empirical study, discussion/policy paper, or technical/policy report (conference abstracts and proceedings were excluded); and (v) the full text was available in English.

Two data extraction templates were developed in the form of Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheets (one for empirical studies and one for other types of publications). Each template consisted of five main sections, corresponding to the predefined specific review questions. Where applicable, codes were applied for further data analysis. For studies with multiple hypotheses and analyses, only those directly focused on FP were extracted. Data from a random sample of 10% of the studies was extracted simultaneously by two researchers and then compared. Any discrepancies were discussed to ensure consistency. Once agreement was reached, data for the remaining studies were extracted by one researcher.

Both quantitative and qualitative (thematic analysis) methods were used for data analysis. For the empirical studies, the research design was categorized using standard classifications: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods approaches. In the case of quantitative research, we further collated the existing evidence according to the type and/or scope of data used (e.g., cross-sectional vs. longitudinal approach, national vs. regional data vs. case study, and the types of hospitals being analysed). For the FP measures, we applied two basic categories, individual indicators and composite metrics, which were further classified into four standard subdimensions (profitability, liquidity, debt management, and asset management indicators) [38]. With respect to the main focus of the included publications, an inductive thematic analysis was applied, supported by mapping the details of the methodological approaches. We distinguished four main categories of empirical study content: (i) measuring and/or comparing hospitals FP (e.g., when statistical methods for group comparison were applied); (ii) identifying association between hospital FP and other hospital characteristics (e.g., when regression models were applied with FP as a dependent or independent variable); (iii) assessing the impact of an event on hospital FP (e.g., pre- and post- analyses); and (iv) other (e.g., application of a hospital performance matrix including financial outcome measures). As the aim was to synthesize and describe the scope of the available evidence, we did not assess the quality of the included studies [34]. Reporting followed the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [39] (Supplementary File 3).

The preliminary review findings were presented during a scientific webinar hosted by the authors’ department (Health Economics and Social Security Department, Institute of Public Health, Jagiellonian University). They were also shared with other relevant stakeholders during an interactive training session with health care organization managers (participants of a postgraduate health care management course). These activities helped to define the most relevant study implications and supported the process of knowledge transfer into practice.

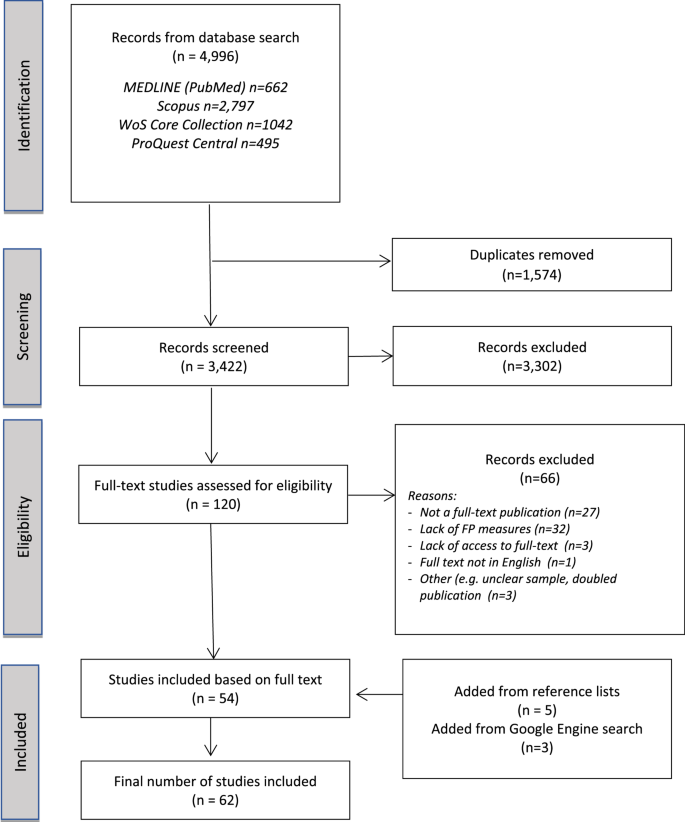

Searches in the four scientific databased yielded 4,995 records. After removing duplicates, 3,422 records were screened on the basis of titles and abstracts, resulting in 120 records chosen for the next stage —full text screening. A total of 54 full-text publications met the inclusion criteria. The most common reasons for exclusion were: lack of full text (e.g., in the case of conference abstracts and/or proceedings) and lack of FP measures (e.g., when FP was not measured at all, or measured at the level of a single service/scope of services). Three additional publication were added from the Google Engine search, and five more were added from the reference lists of the included papers. Thus, the final number of included publications is 62 (Fig. 1).

Among the 62 included papers, there are 53 empirical studies, five policy/discussion papers, and four technical reports. Supplementary File 4 presents the list of included studies with full reference data and the type of study classification. The included publications focus on 13 European countries (excluding two studies [24, 40] that have a multi-country settings). Four countries dominate as publication settings: Poland (n = 18/62), the United Kingdom (n = 10/62), Germany (n = 9/62), and Spain (n = 7/62). Approximately half of the included publications (n = 33/62) were published recently (since 2020). Among the nine nonempirical studies (Supplementary File 5), most focus on presenting the legal background and evaluation/discussion of policies aimed at mitigating the financial debts generated by public hospitals in Croatia [22, 24], Italy [41], Poland [21, 24, 27, 42], and Slovenia [23]. There are also two technical reports focused on policy analysis: one on hospital bankruptcy issues in the Netherlands [43], and another on the hospital-driven payer deficit in the United Kingdom [44].

Studies design

Table 2 presents a general overview of the included empirical studies (ordered by year of publication). As expected, quantitative-based research prevails, with only three out of 53 empirical studies following a mixed methodological approach by including a qualitative component (interviews with relevant stakeholders) [45,46,47]. In the majority of studies (n = 37/53), the data had a longitudinal character, usually covering few years, with only four studies with data covering more than a 10 years period [48,49,50,51]. However, in many cases, despite the use of longitudinal data, the analyses had a cross-sectional character (e.g., when the conducted analyses did not include changes over time but focused solely on associations between FP and other variables). Most studies (n = 42/53) included a national sample of hospitals, although the number of analysed hospitals varied widely. Additionally, the majority of studies (n = 28/53) focused specifically on publicly owned hospitals (Table 2). Secondary data sources were most commonly used, e.g., financial statement registries and national health care administrative databases. In the majority of empirical studies (32/53), the authors have described the theoretical background by directly referring to a chosen economic theory (10/53) and/or developed their economic model based on literature review of related research (22/53) (Supplementary File 6).

Main focus of the studies

The main focus of the included studies can be categorized into four main domains, with some studies covering two, or even three of them (Table 2). Twenty studies focused on measuring and comparing hospital FP (e.g. by applying simple statistical group comparisons). The most common comparison criteria were hospital ownership status and location (e.g., region, urbanization status, population density) (Table 3). The highest number of studies (n = 38/53) focused on measuring associations between FP and other hospital characteristics, usually via regression models or correlation analyses. Three types of hospital characteristics were most often applied (analysed in eight, 19, and eight studies, respectively): ownership, management style/characteristics (e.g., board composition and/or characteristics, the scope of corporate social responsibility activities), and financial features (e.g., asset value, working capital) (Table 3). Eleven studies focused on analysing the impact of an event on hospital FP (e.g. via pre- post- analysis), with the COVID-19 pandemic and organizational changes at the hospital level being the most frequently analysed. Finally, six studies included other types of analysis, with most of them focusing on hospital FP as one of the dimensions of the complex hospital performance matrix (Table 3).

Financial performance definition and measures

In the vast majority of the included studies (n = 47/53), individual/single indicators were used to measure hospital FP. Depending on the study, the number of such indicators could vary from one to more than twenty (Table 2). Only six studies applied a composite measure of FP. Of these, three used the composite measures calculated on the basis of the existing regulations on monitoring public hospitals’ FP [80], reports related to financial marker analyses [52], or retrieved from existing audit reports [54]. In the remaining three studies, the authors applied their own estimations [67, 79, 86]. In most cases, the composite measure calculation formula consisted of approx. 10 individual indicators. Across all included studies, profitability measures were the most commonly used. Specifically, 28 studies exclusively applied profitability indicators, whereas an additional 14 studies combined profitability measures with indicators characterizing other FP dimensions (debt management, liquidity, and asset management) (Table 2).

Study results

The vast majority of the included studies reported numerous —and often mixed —results. This was driven mostly by the broad scope of analyses conducted, with multiple models and/or variables, which makes providing a comprehensive summary and/or comparison of the results challenging. Consequently, Supplementary File 6 lists the main results for each included study, while Table 4 shows examples related to the four most commonly analysed variables: hospital ownership, localization, management style/characteristics, and financial features.

In general, the results of the included studies are highly specific to the context, data and methods. The same study may provide contradictory results depending, i.e., on the chosen metric to measure FP. In terms of hospital ownership, the evidence points to better FP among private hospitals compared to public ones (studies from Germany [52, 53, 59] and Portugal [60]), and the existence of differences in FP between public (studies from Poland [19, 87]) as well as private (study from Spain [69]) hospitals with different owners (Table 4). Hospital located in larger cities tend to have better FP than those in rural areas do (evidence from Spain [63] and Poland [66]), yet this might be highly dependent on the choice of FP metrics (Table 4). The evidence on the associations between hospital board characteristics and composition (e.g., size, share of physicians, share of women) is mixed, with some studies showing positive and some negative or no association. For example, a recent study from the UK has shown that there is no associational between a hospital board’s size and its FP (measured by return on assets) [89], while research conducted in Portugal showed a positive correlation between board size and short-term debt ratio [94] (explained by the assumption that the more members of the hospital board has, the higher the risk of conflict of interests and the lower the ability of efficient decision making). A similar situation occurs with hospital involvement in corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, with some studies showing a negative and some a positive association with hospital FP (Table 4). One study from Spain [64] and one from Portugal [94] showed a statistically significant association between CSR involvement and lower profitability and higher indebtedness, respectively, whereas two other studies from Spain [73, 84] showed the statistically significant opposite direction of the association. The negative association between CSR activities and hospital FP was explained by the authors as being due to the need for higher hospital spending, especially in the first years of CSR activities implementation, while the positive one was assumed to be related to the hospital’s higher social status, prestige and thus market share. Finally, there is a group of studies showing relationships (e.g., correlations) between different financial indicators, whose results are highly specific to research context and the choice of variables (Table 4).

Limitations of the studies

In most studies, the authors reported limitations of the conducted analyses, related either to data (n = 19/53) or to both data and methods (n = 21/53). The small sample size was often mentioned as a reason for the limited generalizability of the results. Authors have also indicated issues related to data incompleteness, e.g., lack of access to certain organizational hospital characteristics and/or care outcome variables, including quality of care indicators. The methodological limitations focused on aspects arising from the chosen approach (e.g., lack of control groups in case studies or inability to identify causality in cross-sectional analyses).

Our study mapped existing evidence on hospital FP across European countries. We included 62 publications, that focused on 13 European countries. Among the 53 empirical studies, quantitative designs using longitudinal datasets and public hospital samples prevailed. The majority of empirical studies (n = 38/53) focused on analysing associations between hospital FP and other (mostly non-clinical) hospital characteristics. These studies usually applied regression models with hospital FP as the dependent variable or simple correlation analyses.

Our results confirm a substantial lack of evidence on the impact of hospital FP on quality of care across European countries [4]. In only two included empirical studies was FP used as an independent variable in regression models: Nagendran et al. 2019 [68] analysed the association between operating margins and clinical outcomes in a group of English hospitals, whereas Vogel et al. 2024 [88] analysed the relationship between hospital profits and digital maturity in Germany.

In general, the design of existing studies appears to be driven by data availability and the context of the national health system. As most studies have utilized secondary data sources (e.g., administrative registries), we can assume that a lack of comprehensive hospital performance data —including medical care outcomes—constitute a major research obstacle in many European countries. At the same time, researchers attempt to address policy-relevant research questions within their national health context. For example, in the case of two countries with high number of empirical research, several studies from Germany focus on, or include, an analysis of the issue of public vs. private hospital ownership [52, 53, 59], as each type represent approximately 50% of total number of hospital beds in the country [95]; in contrast, researchers in Poland mostly focus on identifying differences among public hospitals with different ownership (e.g., territorial self-governments, universities, and ministries) [19, 75, 87] as private hospitals play a minor role within the Polish health system [96].

Researchers rarely use composite metrics to measure hospital financial performance (in 47 out of 53 empirical studies, only single/individual indicators were used). At the same time, the majority of included studies rely solely on profitability measures. We assume that this might have been driven by the data availability (e.g., via financial statement registries) from the one hand, and the popularity of profitability analyses in financial management in general, from the other. However, in the predominantly public hospital ownership systems in Europe, financial profitability measures may have limited relevance [20, 97]. By principle, public hospitals do not pursue the profit maximization objective [98, 99], while their operational performance might be more directly impacted by the ability to settle current financial liabilities (e.g., paying pharmaceutical suppliers or hospital staff’s wages on time). In general, using individual financial indicators allows for measuring only a limited scope of hospital FP dimensions and may yield contradictory results (e.g., when profitability is high, yet with simultaneous low liquidity). In contrast, composite FP measures allow for a more comprehensive and reliable assessment [10, 15]. They can be constructed by applying predefined mathematical formula and utilizing several individual indicators. For example, in two recent studies from the US [10, 15], the composite score of hospital FP was developed on the basis of 30 and 17 individual financial indicators, respectively, whereas in Poland, such a measure was defined by dedicated Ministry of Health regulation on monitoring the financial situation of public hospitals and covers nine individual metrics [100]. In all three cases, the composite measure covers individual indicators related to different financial performance areas, e.g., profitability, liquidity, assets, and debt management, allowing for comprehensive assessment.

Our results indicate limited availability of robust, European-based, quantitative evidence on the drivers and impacts of hospital FP. Most of the included empirical studies had a relatively small sample and/or analysed associations, but not causality. At the same time, the individual studies’ results are often mixed and highly dependent on the choice of variables, model design and the study context. This, however, is in line with the results of reviews of empirical studies on hospital FP from other geographical locations, mostly the US [4, 12, 14, 99, 101]. For example, Shen et al. [99, 101] have proven that the magnitude of identified differences in FP of US hospital with different owners can be mostly explained by the individual studies’ research focus and methodology (e.g., number of included confounding factors and data sample size). Similarly, a scoping review of 60 empirical studies analyzing associations between hospital FP and quality of care (including 55 US-based studies) [4] showed that the results might be highly depended on the choice of metrics for both FP and quality of care.

Overall, our results seem to strengthen the presumption of a partial disconnect between economic theory and empirical evidence on hospital performance [99, 102] i.a. due to the high complexity and data intensity of such research. For example, in a group of (included in our review) studies on the association between hospital board characteristics and financial performance [55, 62, 72, 82, 84, 89, 91], the researchers usually applied several different, sometimes conflicting or complementary economic and management science theories (e.g., agency theory, resource-dependence theory, stakeholders theory, stewardship theory, upper echelon theory) and/or developed new conceptual models. Individual theories, previously applied to non-healthcare sectors, need to be contextualized to address the complexity of the possible associations between hospital performance and governance models (especially in the context of public hospitals). The highly mixed results (e.g., negative [72] vs. no-association [82] between physicians/clinicians board membership and hospital FP; negative [89] vs. positive [91] association between gender diversity (share of women) and hospital FP) appear to confirm these challenges as well as point toward the potential existence of a replicability crisis in this field of research. This research phenomenon, originally identified in medical research, has been recently analyzed in other disciplines, including health sciences and economics [103, 104]. It emphasizes the problem of low reproducibility of empirical results which among other consequences, undermines the credibility of the theoretical background used [105].

There are several limitations to our work. First, the language restriction: we included only studies published in English, which means that potentially relevant publications in national languages may have been omitted. Second, we did not have access to the full-texts of three potentially relevant studies (as shown in Fig. 1). Additionally, we did not assess the quality of the included studies and provided a rather broad picture of the analysed topic. While these align with scoping reviews’ methodological guidelines [33, 34], they limit the depth of analysis and interpretation of study findings. Regardless of these limitations, we were able to map existing evidence and build a knowledge base on the topic of hospital financial performance in Europe.

Our review provides implications for both policy and future research. In terms of the former, building robust data infrastructure systems for hospital care including both inputs and performance metrics, e.g., quality of care measures, is a prerequisite for any type of valid research effort focused on hospital sector analysis. Many of the studies included in our review focused on variables that are not directly linked to patient care (e.g., correlations between different type of financial indicators) or relied on proxy measures for hospital outcomes, making it difficult to formulate clear policy implications. Although numerous included studies focused on Central and Eastern European countries, where public hospitals constantly face financial deficits [24, 106], we found no evidence on the impact and/or associations of these financial difficulties (i.e., debt generation) on actual patient care. This gap may be due to a lack of adequate secondary data sources (e.g., public reporting systems on hospital care quality) and significant organisational or methodological challenges in collecting such data through dedicated research (e.g., multi-hospital survey studies). Another, more indirect reason may be related to the general ‘acceptance of public hospitals financial difficulties as a natural consequence of their social functions’. This translates into downplaying the relevance of and/or interest in the problem of public hospitals’ financial deficits, as governments are expected to repeatedly launch bailout programs. The phenomenon of public hospitals’ soft budget constraints has been discussed in the literature [20, 107, 108], where it has been shown to undermine efforts aimed at improving hospital sector efficiency. Regardless of the reasons that have driven the identified research gap, our study provides strong implications for future research. Even in the absence of national-scale data, future studies could focus on individual hospital cases and use longitudinal analyses to assess the impact of hospital FP on quality of care. Such studies could help answer critical questions, such as: Does hospital financial insolvency impact waiting times, patient satisfaction, or clinical care outcomes?. At the same time, dedicated qualitative research (e.g., in-depth interviews with hospital managers) may help to identify the scope of associations between hospital FP and direct patient care characteristics. In addition, more conceptual and methodological work is needed to define best practices in metrics used to define hospital FP in the European context. Such work requires building, testing and validating dedicated models on the basis of empirical data [10]. Taking into account the diversity and discrepancies of individual studies’ results (especially when individual metrics were applied) building composite metrics of hospital performance that would be tested on relatively large, representative sample might provide stronger contribution to the economic theory. Finally, as our review mapped studies focusing on similar objectives and applying the same variables (e.g., impact of board characteristics on hospital profitability), a targeted, narrowly defined systematic review (e, g., with results meta-analysis) might provide stronger evidence for policy-making.

Research evidence on hospital financial performance in Europe is available for a limited number of countries. The existing empirical studies often apply single profitability measures and focus mostly on relationships between hospital FP and other hospital organizational characteristics (e.g. ownership, management style/characteristics). Our review highlights two major research gaps: the lack of evidence on associations between hospital FP and quality of care metrics, and the need for theoretical/conceptual work on composite FP metrics that would be relevant for hospital care providers.

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

- CFO:

-

chief financial officer

- CHEs:

-

current health expenditures

- CSR:

-

corporate social responsibility

- EU:

-

European Union

- FP:

-

financial performance

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States

No dedicated funding.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Dubas-Jakóbczyk, K., Ndayishimiye, C., Szetela, P. et al. Financial performance of hospitals in Europe – a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 25, 933 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-025-13080-2