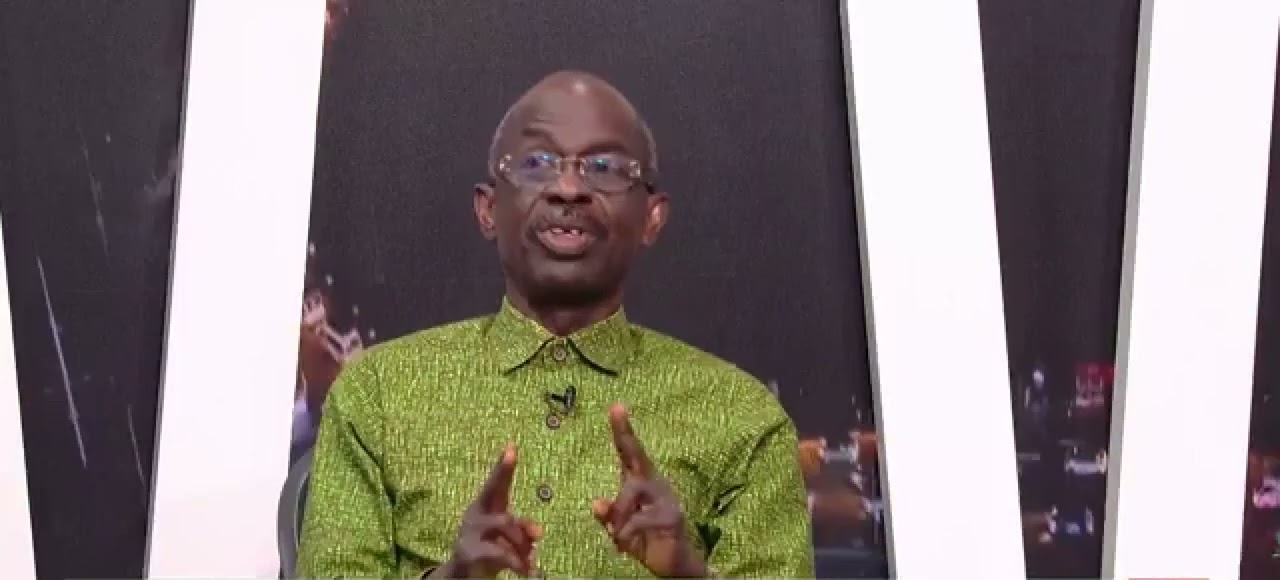

FII Interviews: In Conversation With Historian And Author Manu S Pillai

FII interviews present a profound conversation with acclaimed author and historian Manu S Pillai. He is widely known for offering an interesting perception of history blended with a complex combination of power, culture and individual agency. Pillai is widely renowned for his meticulous research and engaging storytelling, which enables an understanding of how history played a large role in understanding gender roles in the modern age and the lessons that can be understood from the past.

Pillai used to work as the Chief of Staff for Dr Shashi Tharoor and has worked with the BBC Incarnation history series and the House of Lords in Britain.

Pillai has a wide array of books, ranging from the first, The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore, which talks about Lakshmi Bayi’s life in Travancore, a critically acclaimed book which received the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar in 2017. His next book Rebel Sultans offersan intense account of the medieval Deccan, whereas The Courtesan, the Mahatma and the Italian Brahmin provides a slice of history through anecdotes. His next book, False Allies (2021), talks about the life of the princely state rulers during the British Raj, especially with patronage to Raja Ravi Varma. The latest book, Gods, Guns and Missionaries (2024) explores the history of Hinduism during a colonial encounter with European Christian powers.

The extensive array of literature relays Pillai’s unique ability to integrate historical research into accessible narratives, which enables one to understand a multifaceted past that is relevant to today’s day and age.

In an interview with FII, Manu discusses examining gender dynamics with an honest understanding of history.

I don’t know if “empathy” is the word I’d use. It has more to do with seeking a sense of historical completeness. For instance, can we understand human history fully if we are unable to “see” women and the role they play? Often female figures and voices are marginalised in the archival record and do not spring out easily. But with some critical thinking, attention to detail, and by actively looking for them, we can read between the lines, find elements that older generations of historians missed or ignored or dismissed, and form a more rounded picture. I think there is also now an acknowledgement that women’s voices have been marginalised—for instance, in my first book, it was clear to me that its protagonist, a female political figure, had been actively written out of history and turned from a key personality into a passing footnote. So I think to understand historical gender dynamics what we need is a healthy sense of skepticism about existing narratives.

Often female figures and voices are marginalised in the archival record and do not spring out easily. But with some critical thinking, attention to detail, and by actively looking for them, we can read between the lines, find elements that older generations of historians missed or ignored or dismissed, and form a more rounded picture.

Some of this is a consequence of personal interests. I try to find somewhat off-beat topics in general, or even with popular topics, to try and analyse them from a new lens or fresh perspective. With women in history, the stories are just so fascinating to start with: a devadasi who establishes a drama company in the nineteenth century; a tawaif who becomes a warrior and ruler in the eighteenth; the sense of dissent and resistance of patriarchal norms you find in the bhakti poetry of Janabai in the 1300s; the way women have been depicted (and sometimes erased) in art; and so on. Such themes always appeal to me. One purpose of historical inquiry, after all, is to try and unearth details that most have forgotten.

Nothing in the past can be understood through simplistic ideas. For instance, the Junior Maharani of Travancore, Sethu Parvathi Bayi, can be perceived as a feminist icon, from one lens. She invited Margaret Sanger to talk about birth control, and she travelled the world, when her marriage deteriorated she didn’t hesitate to live separately from her husband despite the criticism this invited, and she eventually became the power behind her son’s throne. But equally, she marginalised her sister, the Senior Maharani, could be vindictive and unsympathetic and was not very popular with her people. That is, while as a woman in a world of men, there is much that is interesting in her, as a political figure she was very polarising—and both of these are interconnected. Certainly, some of this was a consequence of patriarchy limiting what she could and couldn’t do because of her gender. Yet clearly she was able to resist it in her way. She wasn’t terribly “likeable” but then again, tough women even today rarely get “liked”.

By asking questions. Romanticisation at one level is inevitable because we all like a good story. But a decent historian must also look past it and understand the context in which these female figures lived, and the conditioning they faced, and then try and unravel their minds and actions.

But a decent historian must also look past it and understand the context in which these female figures lived, and the conditioning they faced, and then try and unravel their minds and actions.

Manu S Pillai: On the one hand, thanks to the matrilineal system, SPB outranked her husband—a situation that amazed observers from elsewhere in India. Technically, he could not take a seat in her presence without her permission. In practice, of course, things were more complicated, and he did try to get her to play the dutiful wife. Equally, thanks to the same matrilineal system, she was always a step below her cousin and rival, Sethu Lakshmi Bayi, and grew to resent this. Ironically it was the birth of a son—the male heir—that allowed Sethu Parvathi Bayi greater prominence.

Matriliny allowed her education and considerable freedom and agency but denied her direct power due to her rank in the family. The birth of a son, however, gave her backseat control, and she would rule through the boy. This invited considerable criticism but Sethu Parvathi Bayi was a determined woman.

FII: As a historian, what are some of how have historical narratives silenced or marginalised the contributions of women?

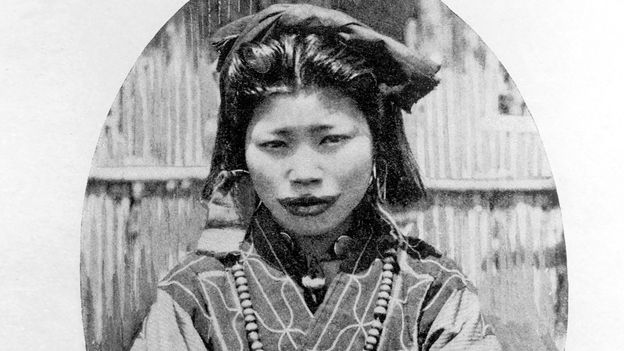

Manu S Pillai: I often give the example of Khunza Humayun, the queen of Ahmednagar in the late 1500s, who ruled that state for some years when her son was a minor. However, in the odd miniature painting that depicted her, she was later erased—quite literally turned into a blob. This was not just marginalisation but an effort to wipe her out of the picture, both visually and in terms of political memory. It was also probably a result of conservative views that frowned on women in purdah being depicted in art. So the lady ruled and held power and played a historical role, but social mores determined how much of her posterity was allowed to see and remember.

FII: What are the main blind spots in history that erase the contribution of women in social reform? What areas of research are critical for historians to explore?

Manu S Pillai: This is a broad subject and there is no one way. One thing that has always amused me is how male reformers of the nineteenth century often gave lectures on women’s rights but hesitated to enact them at home with their spouses and female kin. There are, of course, exceptions such as Jotiba Phule who supported his wife Savitribai, enabling her education and empowering her as a partner in his reform activities. We also have examples like Rukhmabai, the doctor who rejected the man she was made to marry as a young girl and fought this in court, despite slut-shaming and worse in the press. Often these stories exist in the margins and good researchers will be able to discover them through a close, critical reading of the material.

FII: What advice can be offered to individuals who are adept at academically understanding history, that is, understanding gender dynamics?

Manu S Pillai: Keep your eyes open, ask questions, and don’t buy into received wisdom uncritically.

Nikitha Sudhir

Nikitha Sudhir was born in the city of Kochi and raised in Oman. She pursued her masters in mass communication from Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham. As a third culture child she always struggled to find her identity. A strong advocate of intersectionality, she spends her time reading and writing