Can AI speak the language Japan tried to kill?

As a child, Sekine's favourite story was about a singing Hokkaido wolf. The narrative had a melodic quality to it, with a refrain oscillating between sung Ainu phrases and barking vocalisations.

But at school, none of Sekine's friends understood Ainu. And while her mother and grandparents knew some phrases in the language, they mainly spoke Japanese. Other adults couldn't speak it at all. She realised that her family's language, and culture, were dying.

Language is the most important thing for us. It’s the connection between our culture and values

There are only a handful of native Ainu speakers left. The language is currently listed by Unesco as "Critically Endangered". Records suggest that in 1870 – one year after Ezo or Ezochi (now Hokkaido) was declared part of Japan – some 15,000 people spoke local varieties of Ainu, and the majority spoke no other language. But various government policies, including the banning of Ainu in schools, almost wiped the language and culture out. By 1917, the estimated number of speakers had plummeted to just 350 and has dropped precipitously since then.

Despite this, Ainu is arguably undergoing a revival. In 2019, Japan legally recognised the Ainu as Indigenous people of the country through a bill that included measures to foster their inclusion and visibility. And now various projects aim to preserve and revitalise the language – including with the help of artificial intelligence. There's a chance that Ainu could survive for generations to come.

Alamy

Alamy

Sekine was born and raised in Nibutani, Hokkaido, where about 80% of residents reportedly have Ainu heritage. But even there, knowledge of the language is scarce.

"I think my family is a unique one," says Sekine. "My mother's side is Ainu and her family is famous for their handicrafts. My [Japanese] father is also an Ainu language teacher. Sekine, who is in her mid-20s, is the creator of a conversational Ainu YouTube channel. "I know I'm special and lucky," she adds.

While much of Ainu's nuances have been lost over time, knowledge survives, including more than 80 different ways of describing a bear, according to her father Kenji Sekine. The language reflects the community's connection with nature, and their reverence of other living beings. "In the Ainu's way of thinking, everything other than human being is 'kamuy' (god or spiritual deity). Some animals are often called 'kamuy,' like 'kimunkamuy' (bear) and horkewkamuy (wolf)," he says.

Although Ainu is recognised as a second national language, it isn't part of the school curriculum in Hokkaido. "Students have no chance to learn about the Ainu culture and language," says Hirofumi Kato, archaeology professor and director of the Global Station for Indigenous Studies and Cultural Diversity at Hokkaido University. "There is only one stereotyped image of Japanese culture and history. The education system [reinforces] this mono-cultural perspective."

This whitewashing of Japanese history makes it difficult for Ainu people to connect with their roots and navigate their identities in modern Japanese society. While renewed interest in Ainu culture has led to more representations of Ainu people in mainstream media (for instance in manga) that have fostered curiosity and understanding of the community – there have also been instances of cultural appropriation.

Growing up, Sekine felt overwhelmed by the pressure to preserve her culture, so much so that she hid her ancestry when she moved away for middle school. It wasn't until she entered university that she gained the confidence to embrace her indigenous identity and actively promote Ainu culture. Now, she's part of a young generation of community members seeking to redefine what it means to be Ainu. "Language is the most important thing for us. it's the connection between our culture and values," Sekine said. "Family too. We have a big family; we get together every night and have dinner. [These] are Ainu values."

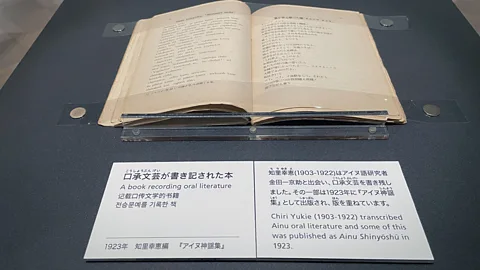

While there are few Ainu speakers around today, there is a rich repository of oral stories. In recent years, researchers have turned to these audio archives with the aim of bringing Ainu back to life.

Alamy

Alamy

"By using our technology, this process has been largely automated. They now have 300 to 400 hours of data," says Tatsuya Kawahara, an informatics professor at Kyoto University, who leads a project using AI speech recognition technology to preserve Ainu recordings. "The sound quality is not so good because many were recorded on analogue devices in houses, where it was sometimes noisy. It's really challenging."

With support from government funding, Kawahara and his colleagues used about 40 hours of recordings featuring uwepeker, or narrated prose stories, from eight speakers shared by the Upopoy National Ainu Museum and the Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum. These recordings are part of a wider archive that in total contains around 700 hours of vocal data collected since the 1970s. Most of the archive is on cassette tapes, just like the folk tales Sekine heard as a child.

In 2015, Japan's Cultural Affairs Agency began digitising these recordings for research and educational purposes, with the AI initiative emerging three years later. Conventionally, automatic speech recognition technology is built using massive datasets that help the system understand the rules of a language before it can transcribe it. However, endangered languages such as Ainu lack such background data, meaning the researchers had to rely on an "end-to-end" model – an approach that allows the system to learn how to process speech into text without prior knowledge of the language.

Kawahara's team is now developing a system for Ainu speech synthesis, which uses AI to generate speech from text. So far, they've successfully trained the AI to emulate speakers who've provided more than 10 hours of recorded speech. The system has even produced speech from the text of two prose stories: Tale of Bear, transcribed between 1950 and 1960; and Raijin's Sister, transcribed in 1958. The AI audio version of Raijin's Sister was shared with the Upopoy National Ainu Museum, in order to train actors for performances. To the untrained ear, the recording – rendered in a voice that could be an elderly woman – sounds eerily natural, with the abrupt pauses and slight tonal inflections you would expect from a real life speaker, albeit slightly too rapid.

"I hope this kind of AI can help people in Hokkaido, Ainu ancestors or young people, to learn the Ainu language," says Kawahara. He suggests that the technology could enable virtual avatars – Ainu teaching assistants that guide young learners of the language. Kawahara's team also hopes to capture more Ainu dialects with AI and include content from younger generations, not just old recordings, he says.

But how accurate are such systems? At present, the AI's translation proficiency is comparable to that of a graduate student of Ainu, the researchers claim. When transcribing some speakers, it has a word recognition accuracy of 85%. The AI's accuracy at recognising phonemes (individual units of sound in a language) can be as high as 95%, though this drops to 93% for unfamiliar speakers using the same dialect, and to 85% for speakers of different dialects.

Sekine doubts the AI's ability to speak Ainu authentically, and is worried that the technology will spread mispronunciations or other mistakes.

At first, many community members contacted by Kawahara and his team were similarly wary of the project and expressed concerns that the technology could create fake speech or spread misinformation, he says. However, those who supported the project have helped check the quality of the transcripts and computer-generated speech, as well as the source data.

Getty Images

Getty Images

"It's difficult to say what I think about [the project]," Sekine says. While such a system could help raise awareness of the language, "Ainu people have to have knowledge about the language, so they can understand what is fake. I would say it's more important to get and verify living data." Sekine has made her own recordings of Ainu stories told by her grandmother and other elderly residents in Nibutani.

That said, her own father, Kenji Sekine, has taken part in the AI initiative. He helped source recordings for Kawahara’s team. While not Ainu himself, he began learning the Saru dialect of the language while helping Sekine's mother run a children's Ainu language class when he first settled in Nibutani in 1999. He eventually took over the course and has been teaching Ainu ever since.

"It's my life’s work," he says. "I want more people to learn. I think the [AI project] is a good thing."

During the researchers' visits to Nibutani, they made rice dumplings together with other residents and attended one of Kenji Sekine's regular classes, which cater to more than a dozen students aged seven to 15. Taught in a circle, the sessions are energetic, and incorporate elements of Te Ataarangi, a method of language teaching emphasising speaking and visualisation, which was developed by Maori people, an Indigenous group in New Zealand.

People continue to coin new words in Ainu, including "imeru kampi" – combining the terms for "lighting strike" and "letter" to create an Ainu word for "email"

"What we're struggling with now is we don’t have many conversational recordings. The [last] person we called a native speaker passed away 20 years ago," Kenji Sekine says.

Keeping Ainu alive is clearly important to this community. But at what cost? Maya Sekine wonders whether the data used to train the AI system will be fully accessible to the public.

David Ifeoluwa Adelani, assistant professor at McGill University's School of Computer Science in Canada and a specialist on low resource languages in Africa, says that Ainu researchers will need to build trust and transparency with the community. "In some cases [of language revitalisation], there's an aspect of, 'You come in and collect data, then you sell it back to us'," Adelani says. "Researchers need to get consent, and then agree on how the data will be used."

This is a particularly sensitive point for people with Ainu heritage because, over the years, Ainu culture has been commodified and appropriated for profit in Japan – via tourism, media and trade, Sekine explains. The threat of further exploitation is a real one for Ainu people, whose land was colonised by the Japanese state. Banned from fishing and hunting for centuries, many Ainu were forced to make a living through farming and low-value labour.

Alamy

Alamy

There are no official statistics on how many Ainu people remain in Japan today, but a survey in 2023 by the Hokkaido Prefectural Government reportedly found that 29% of Ainu people have experienced discrimination, a 6% increase from the previous poll in 2017. Local media reports also suggest that Ainu people earn lower incomes than the national average and are also more likely to experience unstable employment.

It's more ethical to train community members on how to use these tools to revitalise their language, rather than swooping in and collecting data, argues Adelani. "We work on very low resource languages with native speakers in Cameroon because they want to work on it. That's why it's important to train community members. If you teach them, they can prioritise."

While some members of the Ainu welcome the government’s recent interest in Indigenous cultural preservation, critics say it has fallen short of addressing historical injustices and providing fundamental rights. Some argue that the Upopoy National Ainu Museum, which houses Ainu human remains that community members seek to reclaim, is yet another continuation of Japan's assimilation policies. "Upopoy looks like another instance of the Japanese exerting their power over the Ainu," Ainu activist Shikada Kawami said in a statement days before the museum’s opening. "I don't know how many Ainu are aware of the degree to which they are still exploited."

According to Kawahara, the National Ainu Museum holds the copyright of the original data used to develop the system, with consent from the speakers' families. The laboratory owns the rights to the AI system itself. "But the system does not work without data," he notes.

In an ideal world, language technology is done by the speakers, for the speakers

In the future, it could be hard to verify the AI's work given the lack of Ainu speakers around, notes Sara Hooker, head of Cohere for AI, a non-profit that serves as the research arm for the technology company Cohere. "When we're thinking about multilingual [systems] and global reach, it's not just about making sure languages are covered, it's making sure the nuances and how people use these models every day is rich enough to serve people."

But AI for speech recognition and generation is developing at a blistering pace, says Francis Tyler, computational linguistics advisor at Common Voices, a crowdsourced multilingual speech dataset initiative run by US non-profit Mozilla Foundation. Today, developers are releasing AI systems that cover hundreds of languages – an impossibility just five years ago, he says.

"In an ideal world, language technology is done by the speakers, for the speakers," said Tyler. He gives the example of Spain, where many machine translation systems targeting underserved languages like Catalan or Basque are spearheaded by members of those communities themselves.

In other cases, where native speakers are rare or non-existent, leaders can ensure that Indigenous communities have agency over how public money is spent to preserve or develop language learning tools. Tyler gives the example of a Sámi language project. Sámi people live in the Sápmi region, which straddles northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula in Russia. "[The Sámi people involved in that project] are the ones making the political financial decisions," says Tyler.

Efforts to improve Ainu representation are ongoing. For Sekine and her father, the hope is that more Ainu people will become fluent speakers in the future, and that Japanese society will come to better understand and embrace this unique aspect of the region's indigenous heritage.

And, there is hope. Younger generations, for example, continue to coin new words and phrases in Ainu, including "imeru kampi". Imeru means lightning strike while kampi means letter – together they have become the Ainu term for "email".

"The language itself won't be the same as in ancient times, but that's okay," Sekine’s father Kenji says. Every language is living, lively – and changing."

--

For timely, trusted tech news from global correspondents to your inbox, sign up to the Tech Decoded newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.