Comment on Screaming Eagles of Mercy by Lynne Attardi

By Paul Woodadge and Kevin Hymel

Around noon on June 6, 1944, a German soldier wielding a machine gun burst into a small church six miles from Utah Beach in Normandy, France, ignoring the Red Cross flag hanging from the door. He had been fighting most of the day against American paratroopers in the towns, farms, and hedgerows. Inside the church, he found wounded soldiers laid out on pews and the floor as two American medics tended to them. The German leveled his MG-42 machine gun at the occupants and prepared to fire, but then he noticed the medics were treating German soldiers as well as American soldiers. He lowered his weapon and headed back to the door. Before he left, he made the sign of the cross then locked eyes with one of the medics. Then he was gone.

The two medics, Tech/5 Robert E. Wright and Private Kenneth J. Moore, with the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, had parachuted into Normandy 12 hours before and had turned the church into a medical aid station in the village of Angoville-au-Plain.

Wright, from Columbus, Ohio, and one of the shortest men in the regiment, enlisted in the Army in November 1942 at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana. He volunteered for the airborne service and joined the 501st at Camp Toccoa, Georgia. Soon after, he attended Surgical Technician’s School at Lawson General Hospital in Atlanta. He completed his training but was kept at the school as an instructor until he complained to one of his officers and returned to the regiment. He claimed to be part Cherokee, but recent historians have pointed out that African-Americans often claimed Native American heritage to enter all-white establishments.

Moore, from Los Angeles, California, and standing more than six feet tall, enlisted in the Army soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor and volunteered to be a paratrooper. He completed his airborne training with the 501st, and, after serving several months as a rifleman with Company D, also went to the school at Lawson General Hospital. He only attended the school for two weeks before rejoining his company and shipping out.

Both men parachuted into Normandy with the rest of the 101st and the 82nd Airborne Divisions. Wright jumped from his C-47 Skytrain and landed safely on solid ground. Moore had a more tortuous jump. His C-47 dropped out of formation with mechanical trouble soon after takeoff from Merryfield, Somerset, England. The pilot successfully landed and the crew was able to fix the wing. The aircraft took off again, but near the drop zone in Normandy a falling bundle of equipment from another plane sheared off part of its right wing.

The aircraft plummeted through heavy flak as the pilot struggled to regain control, throwing the men around the cabin. Moore picked up one of the shorter paratroopers and helped him attach his static line to the anchor line before throwing the man out the open door. As Moore exited, the C-47’s prop blast tore off his leg bag, crammed with most of his medical equipment. His parachute deployed only seconds before he splashed down into a few feet of water. Wind blew his parachute, dragging Moore through the water until he managed to cut himself free with his jump knife.

Meanwhile, Wright walked for almost two hours through swampy terrain until he came to the church. A young girl accompanied him and pointed out that the area was free of Germans. Wright decided the church would make a good aid station and draped a Red Cross flag over the door. Moore arrived soon after, having treated four paratroopers for wounds and parachute injuries on the way. The sun had yet to rise.

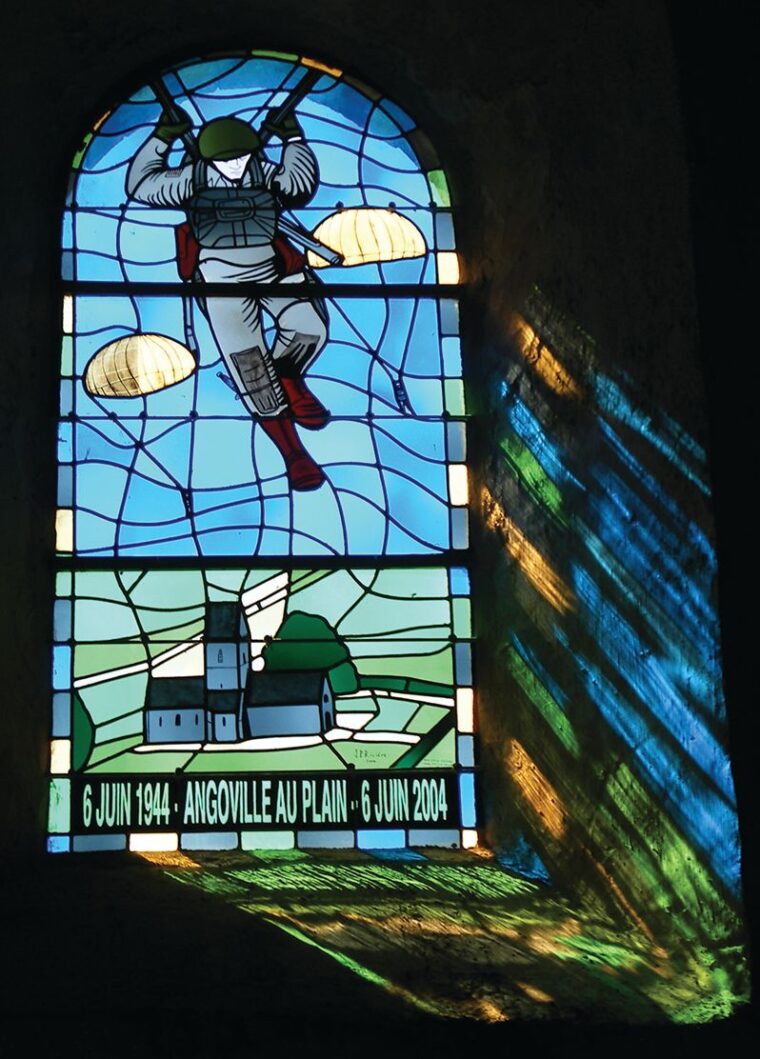

Dating back to the 12th Century, the Church of Saints Cosmas and Damien (Église Saint-Côme et Saint-Damien) had statues of the two saints near the stone altar. A wall and large trees surrounded the churchyard. The wall included fish-bone carvings—symbolic of the area’s fishing trade.

Silently noting each other’s medical armbands, the two men began carrying wounded paratroopers inside and laying them on the pews, where their blood stained the wood. Word quickly spread that the church had become an aid station.

The medics positioned the wounded on the pews with their heads toward the aisle. As more wounded arrived, they resorted to placing them on the floor. Men with light wounds sat on benches that lined the walls near the altar. Moore and Wright wrapped the men in parachute sections to fight off the chill inside the church.

Ever mindful of maintaining morale, Wright followed triage protocols by separating the men by the severity of their wounds. Those with non-life-threatening injuries, either men lightly wounded or those in need of extensive assistance, were kept in the pews, the gravely wounded were placed near the altar, and those who seemed close to death were placed in the Sacristy area behind the altar, where they were given morphine and kept as comfortable as possible.

Both Wright and Moore insisted that, in order to keep the church neutral, no weapons would be allowed inside. Wounded men from both sides stacked or piled their arms outside the door before entering.

Outside, seesaw fighting continued between German paratroopers (Fallschirmjäger), and American paratroopers, mostly from the 501st, as both tried to get the upper hand. Bullets ricocheted inside the church while artillery explosions shook the structure, releasing dust that floated down from the ceiling. Exploding mortar rounds shattered the ancient stained glass windows. One of the wounded soldiers, lying on a pew, quickly rolled under it to escape the falling glass. He later recalled, “Hearing the glass and a wounded soldier calling out for his mother did not do anything for your morale.”

Before noon, an ad hoc group of American paratroopers from Company C of the 326th Engineer Battalion, Company F of the 506th, and other strays, finally pushed the Germans out of Angoville.

Throughout the fighting, the two medics only left the church to retrieve wounded and draw water from a pump, which they then used to clean wounds and keep men hydrated, preventing shock. Moore departed more often than Wright since Wright had completed more medical training. Moore often moved the wounded in a wooden farm cart he found outside.

At times, the medics ventured out together to nearby farm houses and manors to retrieve the wounded from the battlefield. Bullets snapped all around but, to the medics’ amazement, neither was ever hit as they dragged their cart around.

Inside the church, Wright worked feverishly to keep men alive as sweat dripped from under his helmet and blood dripped from his hands. Darting from pew to pew, he expertly tried to stop bleeding, set broken bones, and stitch open wounds. He also offered men water and tried to keep them as comfortable as possible.

The medics worked on everyone, no matter how catastrophic their injuries. When paratroopers brought in a comrade who had almost half his face blown off, Moore worked on his injuries in a desperate attempt to save the man’s life. His efforts unfortunately failed, and the paratrooper was brought out behind the church for burial.

When Moore departed to pick up more wounded, he encountered a paratrooper with bullet wounds to his legs whose buddies had just dropped him off. As Moore helped the soldier onto his cart, another paratrooper wished his wounded friend good luck and waved to him. Then the paratrooper told Moore about another buddy nearby who had been wounded by a mortar round. Moore found the man and brought him to the church for treatment.

From time to time, the medics asked soldiers to head out in search of medical supply bundles dropped from C-47s, but they always came back empty. The medics would have to make do with the scant medical supplies they had or what they could lift from soldiers’ medical packs. As the day wore on, the medics saw fewer jump injuries and more battle injuries.

With two other soldiers helping him, Moore stepped outside to find two wounded paratroopers standing in front of the church. One, Sergeant Edward Hughes, fired on a concealed German sniper with an M3 grease gun in one hand, while he held his swollen eye open with his other. His other eye dangled from its socket. The other paratrooper, PFC Charles Ray Johnson, had already received multiple wounds, including a glance to the scalp from the concealed sniper. Both men were from Fox Company, 501st. Moore and his two helpers brought the men into the church.

Moore laid Johnson on the church altar and Hughes on a pew. He then washed the congealed blood from Hughes’ face and eyes. When Hughes regained his sight a little later, he credited Moore. Johnson’s injuries, however, were grave. When Moore brought him some hot bullion, Johnson told him, “Give it to someone else as I’m not going to make it.” Moore tried to reassure Johnson, but he passed away a little after midnight and was also brought behind the church for burial.

On another trip outside, Moore found Private James Luce, also from Fox Company, lying in a pool of his own blood with his right hand almost severed. With enemy machine-gun fire cutting the air, Moore grabbed some parachute silk from his cart, crawled to Luce, rolled him onto the parachute, and dragged him to safety. He then placed Luce on the cart and quickly wheeled him back to the church. After laying him on the floor between pews, Moore realized Luce’s entire arm was only held on by tendons. He cleaned the wound and applied a tourniquet. When Moore realized that Luce could not survive without a plasma infusion, which was not available, he moved him to the sacristy area where he died later that night.

Moore treated two other Fox Company paratroopers: Clifton Moore and Blanchard Carney. Clifton Moore’s wounds were only superficial and, after treatment, he returned to combat.

Moore also picked up a rather large paratrooper named Ed Turer, who had been a boxer in civilian life. Turer had been hit in the face with shrapnel from his own hand grenade, which had bounced off some foliage when he threw it. Moore and another soldier picked up Turer (they did not have the cart with them) and attempted to carry him back to the church, but, just as he reached the door, he collapsed. “Sorry,” Moore told Turer as he sprawled out in the dirt and gasped for breath, “I just can’t get you any further.” “That’s all right,” Turer responded, “I can walk,” and he stepped into the church and sat on the floor.

Later that afternoon, the German with the MG-42 machine gun burst into the church. After he lowered his weapon and locked eyes with Wright, Wright considered the German his comrade, if only for a brief second.

For the rest of the day, the Germans left the church alone. Wright later recalled that the enemy appreciated what was going on in the aid station. One German dropped off two wounded comrades and other Germans helped carry wounded on stretchers into the church.

From time to time, enemy mortars landed on or around the church. Late in the afternoon, a mortar round hit the roof and exploded, dropping a piece of plaster onto Moore’s unhelmeted head. A bit later, another mortar crashed through the roof and fell to the floor between the rows of pews filled with the wounded. The mortar cracked one of the stone squares on the floor but failed to detonate. Wright quickly scooped it up and tossed it outside. The single round, exploding inside the confined space of the church, could have easily killed them all.

That evening, paratroopers brought in Capt. Bill Osborne, Company D’s commander. He had been found in a tree with two broken legs, one bent directly in front of him. Moore and Wright set his legs in splints.

As the sun began to set, an officer ran into the church and declared: “We can’t hold the village, the Germans are everywhere. We’re falling back to the DZ [Drop Zone]—we’ve gotta go right now!” The officer gave Moore and Wright the choice to pull back with the Americans or stay in the church and continue to treat the wounded. Both elected to stay.

By now, wounded American and German soldiers packed the small church. Some of the Germans eventually departed and returned to their positions. When Wright ran across them while looking for wounded, they simply waved to him.

Almost immediately after the Americans pulled back, the German Fallschirmjäger dug in around the church and set up their machine guns. A German officer, accompanied by two enlisted men, showed up at the church, and Moore told the small party they would have to leave their weapons outside if they wanted to come in. Surprisingly, the Germans complied. The two medics explained that they were treating the wounded but needed a doctor. Without responding, the officer walked the cramped aisles, looking intensely at the wounded. When he noticed Germans lying next to Americans, he relaxed. The officer told Moore that he would send a doctor and advised the medics to stay inside the church.

The two medics went back to work until, a few hours later, another German officer, wounded in the groin and wielding a pistol, tried to enter the Church. Wright, who happened to be standing near the door, drew up his short self and blocked the doorway, insisting that the officer drop his pistol outside before he could come in for treatment. At first, the enraged officer threatened Wright, but common sense took over and he reluctantly sat down outside the church and awaited treatment, still with his pistol holstered.

Wright held his ground. Every time he passed the door on his rounds, he reached out and tapped the officer’s pistol handle and pointed to the pile of weapons. Finally, after a few hours and a loss of blood, the officer drew his pistol and handed it to Wright. Then both medics cleaned his wounds, bandaged him, and offered him water. When they tried to administer morphine, the officer refused and chose to simply sit on the floor grimacing in pain.

Moore and Wright worked well into the night. Moore, having exhausted himself retrieving wounded, finally dozed off for a few minutes. Any peace the medics might have found was quickly shattered when another mortar barrage hit the village.

Soon after the smoke settled, two teenage German soldiers poked their heads out from the belfry’s rafters and looked down on the shocked medics. They then made their way down to the first floor. The two terrified boys were not Fallschirmjäger but possibly artillerymen. Wright told them to sit down, keep their mouths shut, and not bother them, but the two young men offered to help and were put to work caring for the wounded.

The next day, June 7, the medics continued to treat the wounded. Around noon, the Fallschirmjäger pulled back from Angoville. The U.S. infantrymen who had landed the day before at Utah Beach had pressed inland, supported by Allied aircraft, naval guns, and massed artillery, and connected with the airborne forces, forcing the Germans to retreat. Paratroopers and an American tank advanced on the town. The tank fired its machine gun at the church door, and bullets ricocheted inside the stone walls, scaring everyone.

Then the tank pulled back to get a better range and opened fire on the windows. Seeing a catastrophe in the making, Wright grabbed an orange smoke grenade—the color for friendly forces—and stepped outside, pulled the pin, and tossed it. As orange smoke spewed from the canister, another church occupant waved an orange marker panel from one of the smashed-out windows. A third paratrooper ran to the tank and grabbed the phone in its rear and told the crew to stop firing. The triple effort succeeded, and the tank moved on.

By this point, the church had filled to capacity. New arrivals were treated outside, but that did not keep them from coming. Paratroopers now delivered the wounded in either an airborne equipment carrier or a captured German Kübelwagen.

At about 4 p.m., paratroopers from the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, supported by two Sherman tanks, advanced into Angoville. One of the tanks roared in the direction of a wounded paratrooper on the equipment carrier. Seeing this, an airborne sergeant fired his Thompson submachine gun at the tank, alerting the tank commander to change course. The tank swerved, narrowly missing the wounded man.

With the area now in American control, a lieutenant with the 501st entered the church to set up an observation post in the tower. Wright refused, explaining the church’s use and the fact that the Germans respected its neutrality. The infuriated lieutenant ordered Wright to step aside, but Wright refused and the lieutenant stomped off.

Later in the day, Lieutenant Colonel Ballard, the 2nd Battalion, 501st commander, arrived at the church and asked Wright about his insubordination. Wright denied that he had been insubordinate but admitted his refusal of the lieutenant’s order. Ballard departed without saying a word. No punishment ever came to Wright.

As the American reinforcements occupied the area, other medical personnel took over the church. It was time for the medics to turn over their aid station. Moore departed and joined his comrades in D Company. Wright stayed another day, helping to move the wounded to the rear before rejoining the regiment. By the end of June 7, the two medics had treated at least 80 casualties in their makeshift medical aid station.

Both Moore and Wright earned the Silver Star for their life-saving actions in the church. Both also survived the war and returned home to marry and have children. Moore worked for Chevron and owned his own gas station. Wright worked in the oil industry and later remodeled gas stations. In their later years, they both attended 501st reunions and returned to the Angoville-au-Plain church. Wright died in 2013 and Moore followed almost exactly one year later.

Today, a memorial adorned with American and French flags stands outside the church, dedicated to both Wright and Moore. Etched onto the bottom of the memorial are the words: “FOR HUMANE AND LIFE SAVING CARE RENDERED TO 80 COMBATANTS AND A CHILD IN THIS CHURCH IN JUNE 1944.”

While Moore and Wright had toiled in the church on D-Day, they might not have noticed several silver-dollar sized seals carved into the stone altar. They had been chiseled by passing Knights Hospitaller, a Catholic military order of knights founded after the Christian conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, to protect a hospital in the city during the First Crusade. The order later expanded to escorting European pilgrims journeying to the Middle East. How appropriate it was that warriors dedicated to healing in the 12th century had left their lasting mark in the church, just like the blood-stained pews left from two 20th century warrior healers.

British writer Paul Woodadge is the author of the book, Angels of Mercy: Two Screaming Eagle Medics in Angoville-au-Plain on D-Day, on which this article is based. He hosts WW2 TV on YouTube and worked as a Normandy battlefield guide from 2002 to 2018. He has also served as a historical advisor and consultant for TV and film projects.