BMC Women's Health volume 25, Article number: 253 (2025) Cite this article

This study aimed to systematically describe the characteristics of bonding disorders and diagnostically classify them using the Japanese version of the 6th Stafford Interview. We investigated the cut-off points of the Japanese version of the Mother-Infant Bonding Scale (MIBS-J) and Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ) to screen for bonding disorders.

We recruited participants in their second trimester and studied 40 mother-infant dyads. At one month postpartum, we conducted the mother-infant relationship section of the Stafford Interview and classified participants into diagnostic groups. We administered the MIBS-J at four days and one month postpartum and the PBQ at one month, combined with the interview. We used the total scores to analyse the receiver operating characteristic curve at four days and one month.

We diagnosed one case of emotional rejection and eleven cases of mild disorder. Additionally, three cases exhibited pathological anger with mild disorder—one with emotional rejection and one infant-focused anxiety case with normal bonding. The screening scores for bonding disorders, including mild cases, were 2 or more points for MIBS-J at four days and 3 or more points at one month. The PBQ was better at identifying severe bonding disorders, with a score of 19 or more points.

Bonding disorders can expose mothers to serious mental and parenting conditions as early as one month postpartum. Questionnaire screening and diagnostic interviews can help with early detection and care.

The pathologies impairing mothers’ positive and affectionate feelings towards their infants are associated with perinatal maternal distress and maltreatment. Kumar [1] recruited 44 postpartum women who had experienced distress from feelings that their baby belonged to someone else and asked them to describe their feelings towards their baby in a letter format. This study showed that some women in the community needed support to alleviate their bonding problems, which led to the development of the Mother-Infant Bonding Questionnaire [2] and the Japanese version of the Mother-Infant Bonding Scale (MIBS-J) [3]. Brockington [4, 5] published a thorough description of bonding problems found in psychiatrically high-risk pregnant women referred for specialised perinatal care and revealed that the core of the bonding disorder was an emotional rejection of the baby. Mothers with pathological anger, in addition to emotional rejection, could abuse their children [6]. Consequently, Brockington et al. [7] proposed diagnostic criteria subdivided into emotional rejection, mild disorder, and additional groups of pathological anger and infant-focused anxiety. Brockington et al. [8] also developed the structured psychiatric interview for the assessment of bonding disorders as one section, ‘The mother-infant relationship’, within the sixth edition of the Stafford Interview [9, 10] and the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ). The PBQ has been translated into Chinese, Spanish, and Tamil and validated using the Stafford Interview as an external criterion [11,12,13].

In Japan, the PBQ and the MIBS-J have been validated and are available through factor analysis and cluster analysis [3, 14,15,16]. As no reports describe the characteristics of each classification of bonding disorder diagnosed using structured interviews with Japanese women, these two questionnaires do not have cut-off values for bonding disorders with clinical diagnosis using the interviews as an external criterion. Brockington gave Yoshida (one of the authors of this paper) permission to translate the sixth edition of the Stafford Interview mentioned above into Japanese, and the authors of this paper completed and published the translation in 2022. Furthermore, as a section of ‘the mother-infant relationship’ within this interview can be used to assess maternal bonding on its own, we have already reported a case of emotional rejection using this interview section in a preliminary study [17].

In this study, we have attempted to classify the diagnoses using this interview method with participants. We described the clinical characteristics and explored the recommended MIBS-J and PBQ cut-off scores for these diagnostic groups.

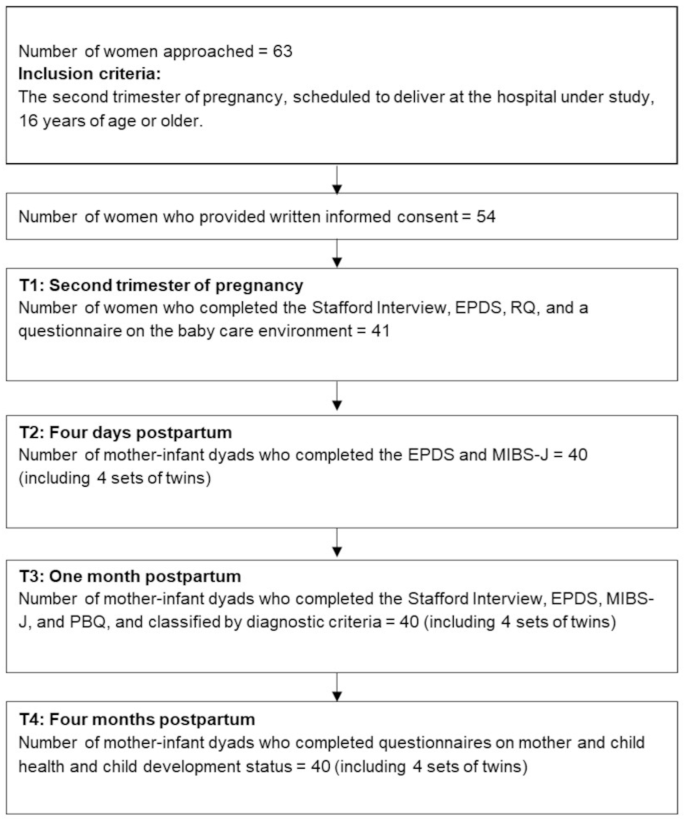

The study was conducted at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Perinatal Mental Health at the University Hospital. We recruited pregnant women in the second trimester of pregnancy who were scheduled to deliver at the hospital. Data were collected between September 2017 and December 2019. The participants were referred from a local maternity clinic owing to physical or psychiatric complications. Of the 63 participants recruited, 54 gave written informed consent, and 40 mother-infant dyads (including four sets of twins) completed the investigations at one month postpartum. The Institutional Review Boards/Ethics Committees of the University Hospital and Medical Institutions approved this study (approval number 2020 − 776).

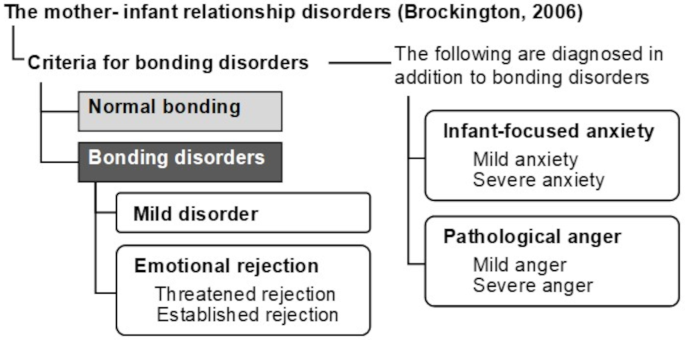

Criteria for disorders of the mother-infant relationship

The Brockington’s diagnostic criteria for disorders of the mother- infant relationship was developed as a revision of 2001 study’s criteria [18], which was used to categorise participants in a 2006 study exploring bonding disorders in 205 mothers referred to mother and infant services in Birmingham and Christchurch [7].

The criteria divide emotional rejection, which is the core element for bonding disorders, into two groups: severe disorder is ‘established rejection’, and rejection below the diagnostic threshold is ‘threatened rejection’. Cases with mild problems below the diagnostic threshold of emotional rejection were classified as ‘mild disorders’, including delayed positive feelings, loss of positive feelings, and ambivalence. ‘Pathological anger’, which is possibly causing harm to the baby, and ‘infant-focused anxiety’, which is avoiding the baby because of anxiety about the baby’s care, are diagnosed, in addition to each level of bonding disorder. This classification is summarised in Fig. 1 (for a detailed description of these criteria, please see Brockington et al.’s 2006 report [7]).

The 6th edition of the Stafford interview

This study administered the mother-infant relationship section of the Japanese version of the Stafford Interview (6th edition) to diagnose bonding disorders. The following sections on pregnancy were also explored, including items for unwanted pregnancy or impaired mother-foetus relationships that had already been reported as precursors of postnatal bonding disorders [6]: Psychological and Obstetric Background to Pregnancy, Response to Conception, and Wellbeing of the Unborn Child. As four sets of twins were included in this study, interviews were conducted with each child’s mother separately (n = 40) according to the interview instructions. Trained professionals conducted these interviews. Two authors, YN (or YS) and KY, rated the interview results. Consensus on the ratings was reached by adding a third rater (YS or HY) and discussing the mothers’ responses.

We explored the course and quality of bonding through the mothers’ narratives drawn from the interviews about their feelings towards their babies at one month postpartum. According to the interview ratings, we classified participants using the aforementioned diagnostic criteria for maternal-infant relationships [7]. The Stafford Interview instructions helped us identify maternal bonding at the time of the interview and at the worst period after birth. We based the diagnosis on responses at the worst point in time.

Next, as we explored optimal cut-off values of the MIBS-J and PBQ for classifying maternal-infant relationship disorders, we grouped them as follows: Group 1: emotional rejection, pathological anger, and infant-focused anxiety (G1); Group 2: mild disorder only (G2); and Group 3: normal bonding (G3). G1 was the severe mother-infant relationship disorder group according to Brockington’s diagnostic criteria [7], requiring intensive care for mother and child; G2 was the group with mild disorders below the mother-infant relationship disorder diagnostic threshold, which also included women at risk of developing severe conditions later; G3 comprised mothers with normal bonding. As G2 may or may not be included in the clinical group defined depending on the clinical setting and the study objectives, we considered both cases in this study. Consequently, two statistical tests were conducted by grouping them as follows:

G1 × (G2 + G3): mothers with severe mother-infant relationship disorder vs. others.

(G1 + G2) × G3: mothers with some bonding problems vs. normal bonding mothers.

The postpartum bonding questionnaire (PBQ)

We used the Japanese version of the PBQ [15]. Items were rated on a six-point scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always), and eight items were reverse scored. Higher scores indicated impaired mother-infant bonding and negative feelings towards the baby.

The Japanese version of the Mother-Infant bonding scale (MIBS-J)

The MIBS-J is a self-report instrument comprising ten items rated on a four-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). High scores indicate that the mother lacks affection for her baby, has negative feelings, and is distressed. The development and validity study of the MIBS-J by Yoshida et al. [3] showed a two-factor structure for lack of affection (LA) and anger and rejection (AR).

The Japanese version of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS)

The EPDS is a self-reported questionnaire comprising ten items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3) designed to assess depression during the perinatal period [19]. A total score of nine or more on the Japanese version of the EPDS is indicative of major depressive episodes, with a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 95% [20, 21]. This validated Japanese cut-off score was used for group comparison in this study to check for the presence of depressive symptoms among the participating mothers [22].

We interviewed women in their second trimester (TI), who visited the obstetric outpatient clinic for regular check-ups, using the pregnancy section of the Stafford Interview (EPDS and demographic background). On the fourth day postpartum (T2), when the women were discharged from the maternity hospital, they completed the MIBS-J and EPDS. In the first month postpartum (T3), when they visited the hospital for their first month postpartum routine check-up, they were interviewed using the mother-infant relationship section of the Stafford Interview. They completed the MIBS-J, PBQ, and EPDS. In the fourth month postpartum (T4), women received questionnaires on mother and child health and child development status by post to complete and return (Fig. 2).

We calculated a weighted Kappa statistic to examine the inter-rater reliability for each Stafford Interview rating. We used Fisher’s exact test with binary variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. We used the statistical software EZR (Easy R) [23] and set the significance level at 5%. We conducted the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) and the area under the curve (AUC) analyses. We used IBM SPSS Statistics v. 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) for these analyses.

The mean age of the women was 32.7 years (SD 5.37). Half of the women (57.1%) had graduated from junior college or college. One-third were employed during their second trimester of pregnancy (33.3%). All but three women were married at the time they gave birth, and all the husbands were employed. Nearly half of the women (46.2%) required a Caesarean section, of which eight were emergencies. The mean birth weight of the infants was 2.81 kg (SD 0.51) with a mean gestational age of 38.4 weeks (SD 1.85), and half were boys. All the babies’ five-minute Apgar scores were eight points or more. No babies had severe medical and developmental problems up to four months postpartum.

First, two raters performed blinded ratings of the interviews. For 19 of the ratings, the two raters’ ratings for all participants matched. The weighted Kappa statistics for the inter-rater reliability of the 14 ratings demonstrated ‘almost perfect agreement’ (0.81–1.0, by Landis and Koch) [24], except for №34, ‘Medical concern about the unborn child’ and №168, ‘Ideas of transferring care or escaping from maternal duties’ (‘substantial agreement’, 0.79 and 0.67, respectively). For the 14 ratings, we reviewed the women’s responses again, adding a third rater for all disagreements to determine the final rating.

Next, based on the women’s responses from the interviews, we classified each participant according to Brockington’s diagnostic criteria for maternal-infant relationship disorder (Table 1): established emotional rejection = 1 (2.5%), mild disorder = 11 (27.5%), and normal bonding = 28 (70.0%). We additionally diagnosed four cases of pathological anger (two severe, two mild) and one case of infant-focused anxiety. We integrated all participant cases into three groups in line with the study method. The participants were classified as G1 (5, 12.5%), G2 (8, 20.0%), and G3 (27, 67.5%).

We summarised the differences in the severity of bonding problems and the clinical course revealed by the narrative responses in the Stafford Interviews of women in the G1 and G2 groups. Abbreviations used in this summary are as follows: ER/PA, emotional rejection with pathological anger; MD/PA, mild disorder with pathological anger; NB/IFA, normal bonding with infant-focused anxiety; MD, mild disorder only. For detailed scores and narrative responses from the Stafford Interview, refer to the Online Resources (Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Summary of women in G1

ER/PA: She wished something had happened to the foetus during her pregnancy to make it disappear. She planned to place the baby in foster care, but her husband refused. She felt the baby was not her own for three weeks after birth. She sometimes wished the baby had never been born. She wanted someone else to take care of the baby permanently. She shouted at her baby 3–4 times and had faint thoughts of infanticide.

After delivery, she felt trapped in caring for her baby, although she had positive feelings. She felt anger towards the baby from around seven days postpartum because of the baby’s night crying, and at about one month postpartum, she shouted at the baby.

The woman thought the baby was beautiful but felt like she was looking after someone else’s baby for a month. She felt angry with the baby when the baby moved and was difficult to feed, so she hit the baby once in the third week postpartum.

She did not find the baby beautiful for the first three weeks postpartum. The woman could not even eat as she had to cope with the baby’s crying. When the baby cried intensely, she felt hostility towards the baby. Twice in the third week postpartum, she covered the baby’s mouth with her hands when the baby cried.

When she discovered her pregnancy, she was highly anxious and confused and denied being pregnant for six months; she secretly considered abortion. Although she had experienced positive feelings about the baby since birth, she transferred baby care to her husband because she was anxious when left alone with her baby.

Summary of women in G2

The symptoms of four women of a total of eight diagnosed with MD were mainly a delay or loss of positive feelings. The other four diagnosed with MD had feelings of rejection or estrangement below the diagnostic threshold with positive feelings towards their babies.

Table 2 shows the background and questionnaire score statistics used to compare the groups, and Table 3 shows the comparison results. Negative reactions to pregnancy and thoughts of abortion were significantly different for Tests 1 and 2. The number of women with EPDS scores above the Japanese cut-off (≥ 9 points) was significantly greater in the G1 group (Test 1) than in the other groups. We found significant differences for Test 2 in the current or previous history of psychiatric problems. The scores on the bonding questionnaires were significantly different for all comparisons of Tests 1 and 2.

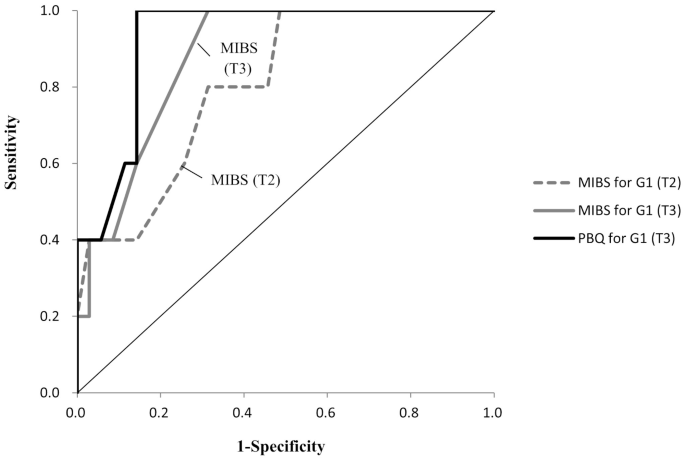

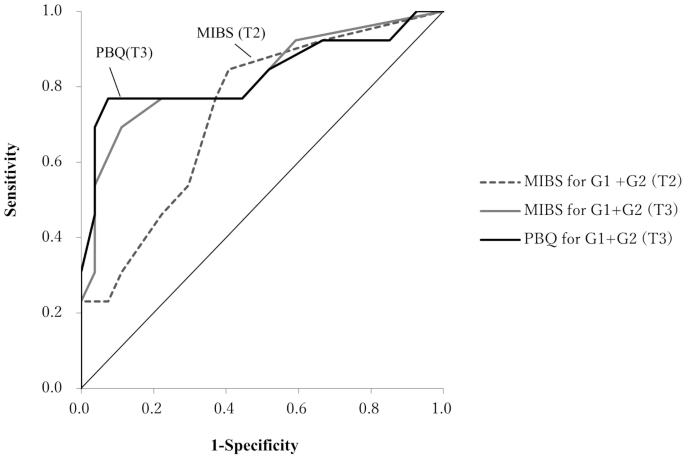

We drew ROC curves (Figs. 3 and 4) and found moderate accuracy on all variables from the AUC analysis (Table 4) with no significant differences between the AUC of each variable. Next, to determine the appropriate cut-off values to identify G1 and G1 + G2 for the total scores on these questionnaires, we used two indices: the Youden index and the Euclidean distance. Where the two did not agree, we predominantly considered sensitivity (Table 5-1 and 5-2). We chose 1/2 at T2 and 2/3 at T3 as the MIBS-J cut-off value to screen G1, and the same applies to G1 + G2. We obtained high sensitivity and specificity cut-offs for the total PBQ score at T3: 18/19 for G1 (sensitivity 1.00, specificity 0.84) and 16/17 for G1 + G2 (sensitivity 0.77, specificity 0.91).

Receiver operating characteristic curve of scores on the MIBS-J/PBQ in the prediction of G1

G1: Group 1: Types of mother-infant relationship disorders (emotional rejection, pathological anger, and infant-focused anxiety), T2: 4 days postpartum, T3: 1 month postpartum

Receiver operating characteristic curve of scores on the MIBS-J/PBQ in the prediction of G1 + G2

G1: Group 1: Types of mother-infant relationship disorders (emotional rejection, pathological anger, and infant-focused anxiety), G2: Group 2: Mild disorder only, G3: Group3: Normal bonding exactly, T2: 4 days postpartum, T3: 1 month postpartum

In this study, using Brockington’s diagnostic classification and the Stafford Interview, more women were diagnosed with mild disorder than with bonding disorder, that is, emotional rejection. Women with mild disorders had positive feelings but weak bonds with their babies, experiencing estrangement from their infants. The narratives of MD/PA women showed that 2–3 weeks postpartum is the first point when anger peaks, owing to baby care exhaustion and sleeplessness. This finding suggests that the coexistence of mild disorder and pathological anger in some women may lead to neglect and abuse if there is no early parenting support—indicating the requirement for early detection of the mild disorder.

The results suggest that mild disorders should be identified early on and included in a group requiring primary care and careful monitoring. If the cut-off values for the women in this study were determined for the early diagnosis and primary care of maternal-infant relationship disorders, including mild disorders (G1 + G2), the cut-off values were a total score of 2 or more points on the MIBS on the fourth postpartum day (at maternity discharge) and with 3 or more points at one month postpartum (at the routine health check-up). However, a total PBQ score at one month after birth (cut-off value 19 or more points, which is lower than that in the UK of 26 or more points [8]) demonstrated utility with high specificity and sensitivity for detecting severe mother-infant relationship disorder (G1), which requires more intensive care.

Finally, although the Stafford Interview is applicable during the first year after birth, the optimal time points in the year for screening and diagnosis of maternal-infant relationship disorder and emotional rejection have not been defined. The results of this study indicate that one of the high-risk time points when maternal bonding problems can lead to abuse and neglect is the first month after birth, especially around the third week after birth. Further studies are needed to investigate how mothers’ feelings towards their babies change after the first month. Though a considerable proportion of women delay the onset of affection towards their babies postpartum, most develop affection for them during the first six months after birth [25]. However, regarding pathological anger towards the baby, Brockington [5] and the current researchers of this study [17] have reported cases of women whose anger emerges later than one month postpartum. In further research, the application of the Stafford Interview in the latter period of the postnatal year is expected to reveal another high-risk time point for mother-infant relationship disorder, in particular, pathological anger.

In this study, we included only five dyads of G1. More cases need to be observed using the interview method to ascertain the features of this group’s pathology in Japan.

The Stafford Interview helps diagnose and describe the clinical features of bonding disorders among Japanese mothers. Furthermore, using the MIBS-J and PBQ in conjunction with the interview for early detection, early intervention, and follow-up of maternal-infant relationship disorders, including bonding disorders, leads to more explicit and systematic mental health services.

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

- PBQ:

-

Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire

- MIBS-J:

-

Japanese version of the Mother-Infant Bonding Scale

- EDPS:

-

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- ER/PA:

-

Emotional rejection with pathological anger

- MD/PA:

-

Mild disorder with pathological anger

- NB/IFA:

-

Normal bonding with infant-focused anxiety

- MD:

-

Mild disorder only

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI [Grant Number 17K12294] and Pfizer Health Research Foundation.

The Institutional Review Boards/Ethics Committees of Kyushu University Hospital and Medical Institutions approved this study (approval number 2020 − 776). All the participants provided written informed consent.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Nishikii, Y., Suetsugu, Y., Yamashita, H. et al. Clinical features of bonding disorders in Japanese mothers derived from the Stafford interview. BMC Women's Health 25, 253 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-025-03795-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-025-03795-z