BMC Women's Health volume 25, Article number: 330 (2025) Cite this article

Physical activity (PA) is essential for preventing chronic diseases and improving mental health, yet global PA levels remain suboptimal, with women generally engaging in less PA than men. This gender disparity is especially concerning for women from ethnic minority groups, who face a higher risk of chronic diseases and encounter unique barriers to PA participation. Understanding these obstacles is crucial for developing targeted interventions to promote PA and reduce health disparities among ethnic minority women. This systematic review aimed to identify, categorize, and synthesize existing research on the barriers to PA among these women.

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Six databases were searched (from inception to December 2024) to identify primary studies of any methodological design (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods) that examined barriers to PA among adult women from ethnic minority groups, excluding African American and Indigenous populations. Studies were included regardless of country, as long as they met the eligibility criteria. Thematic analysis, guided by the social-ecological model, was used to synthesize the findings.

Sixty-four studies involving 5,555 women and conducted in 12 countries met the inclusion criteria. Thematic analysis identified 16 barriers categorized within the social-ecological framework. At the individual level, common barriers included time constraints, lack of motivation, poor physical health, and disinterest in PA. Interpersonal barriers, such as family responsibilities, cultural expectations, language barriers, and lack of social support, were prevalent. Environmental barriers included unsafe neighborhoods, limited access to PA resources, and inadequate infrastructure. Regional differences were observed, with cultural barriers and family obligations most common in the Americas, and misconceptions about PA and environmental factors more prevalent in the Eastern Mediterranean. Socioeconomic status and immigration status exacerbated these challenges.

This review highlights the complex, multi-level barriers that ethnic minority women face in engaging in PA. Addressing these challenges requires multifaceted interventions that consider individual, interpersonal, and environmental factors. Future research should explore strategies that reduce these barriers and promote equitable access to PA opportunities for women from ethnic minority groups.

Regular physical activity (PA) is widely recognized for its role in preventing chronic diseases [1], improving mental health [2], and enhancing overall quality of life [3]. Given these well-documented benefits, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a minimum of 150 min of moderate-intensity or 75 min of vigorous-intensity PA per week to achieve significant health gains [4]. However, despite strong evidence supporting its positive impact, global PA levels remain suboptimal [5], particularly among women, who consistently engage in less PA than men [6].

This gender disparity in PA is particularly concerning given that women face a higher risk of developing chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, when compared to men [7]. Biological factors, hormonal influences, and the compounded effects of physical inactivity (e.g., hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes) contribute to this elevated risk [8]. Beyond physiological differences, women encounter numerous social, cultural, and environmental barriers that further limit their participation in PA [9]. Caregiving responsibilities, workplace inequities, safety concerns, and deeply ingrained gender norms often restrict opportunities for regular PA engagement [9]. Additionally, cultural perceptions that certain forms of physical activity - such as vigorous exercise or outdoor sports - are less suitable for women can further discourage their participation [10]. For example, among South Asian immigrant women in Western countries, cultural norms emphasizing modesty and traditional gender roles often discourage participation in vigorous or outdoor sports, limiting their engagement in such activities [11]. Acculturation - the process by which individuals adopt the cultural norms and behaviors of a new society - can also influence physical activity levels, shaping women’s perceptions, motivations, and engagement [11, 12].

These constraints are even more pronounced among women from ethnic minority groups, who often experience intersecting social and economic disadvantages [12]. Ethnic minority groups are defined as populations that differ from the dominant cultural or racial group in a given society. Limited financial resources, reduced access to healthcare, language barriers, systemic discrimination, and the absence of culturally appropriate recreational spaces present significant challenges to PA engagement [13]. These structural inequities not only widen health disparities but also hinder the development of effective interventions tailored to the specific needs of ethnic minority women [12].

Despite increasing awareness of the disparities in PA, research on the specific barriers faced by ethnic minority women remains limited. A comprehensive understanding of these barriers is crucial, as it highlights the unique challenges that prevent these women from engaging in PA and helps pinpoint areas where interventions are most needed. This systematic review aimed to identify, categorize, and synthesize existing research on the obstacles that limit PA participation among women from ethnic minority groups. By systematically examining these barriers, this review aims to contribute to the broader field of health equity by identifying strategies to reduce disparities and promote greater physical activity engagement in these populations.

The reporting of this study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [14]. This systematic review was prospectively registered at the Open Science Framework (OSF: https://osf.io/r5h3c/).

The “PICO” framework was employed to define the search criteria for this review, specifying the population, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and types of studies to be evaluated. The population included adult women (18 years and older) from ethnic minority groups, defined as populations within a society that have distinct cultural, ethnic, or linguistic identities differing from the majority population [13], including first- and second-generation immigrants. Studies focusing exclusively on African American and Indigenous women were excluded due to their unique political, historical, and social contexts.

The intervention was broadly defined as participation in any form of PA, including structured exercise, recreational activities, and active transportation. To ensure consistency in study selection, PA was defined according to the WHO [4] as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure, encompassing activities of varying intensities such as walking, sports, and household tasks. No comparators were specified in this review. The primary outcome was the identification of at least one barrier to PA participation among the target population. Additionally, studies addressing specific conditions, such as pregnancy, menopause, cancer, or diabetes, were excluded, as the barriers to PA in these contexts are highly specific and differ from those faced by ethnic minority women in general.

Primary studies of any methodological design - quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods - were eligible for inclusion, provided they were peer-reviewed. Narrative, systematic, and scoping reviews were considered as a source of additional primary studies. Studies published in any language were eligible for consideration.

The following databases were searched from their inception up to December 2024: Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), APA PsycInfo, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; EBSCO), and Web of Science. An Information Specialist (EM) developed the search strategy using the PICO framework outlined above, incorporating relevant subject headings for each database and free-text terms aligned with the key concepts. Additionally, studies identified through a snowball hand-search were also considered for inclusion. The complete search strategy is provided in the Supplementary Material 1.

Duplicate citations from the databases were removed using Covidence software. Three researchers (APDBB, IRM, and GLMG) independently screened all references identified by the search strategy, focusing on titles and abstracts. To be eligible, abstracts had to specifically address barriers to PA identified by women from ethnic minority groups, excluding studies that combined data from men-only or other ethnic groups. Studies were included regardless of country, as long as they met the eligibility criteria. Full-text articles of potentially eligible studies were obtained and independently assessed by the three reviewers to determine their suitability based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements encountered during the screening were discussed among the researchers and resolved to refine the results.

Two researchers (APDBB and IRM) independently extracted data on the following using a standardized form: country where study was conducted, study design, purpose, ethnic minority group, country of origin, total sample size, women sample size, measurement tool and barriers to physical activity. The extracted data were then reviewed and validated independently by a second researcher (IRM). Any disparities were resolved through consensus among the three researchers (APDBB, IRM and GLMG).

To assess the methodological quality of the selected studies, two authors (APDBB, IRM) independently appraised each included study using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [15]. The MMAT is suitable for evaluating a range of study designs, including randomized controlled trials, descriptive studies, mixed methods, and qualitative research. For each design, five appraisal items are assessed, with responses categorized as present (yes), not present (no), or unclear. Each “yes” response contributes 1 point, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 5. Higher scores (i.e., ≥ 4), indicate higher quality assessments of the studies. Any discrepancies in the ratings were resolved through discussion with the senior author (GLMG). Low quality studies were not excluded, but caution was taken when interpreting their results.

A thematic analysis was conducted by two authors (APDBB and GLMG) to systematically identify, analyze, and categorize barriers to PA extracted from the included studies [16]. This analysis was guided by the social-ecological (SE) framework [17], which considers the multiple, interconnected levels of influence on behavior, including individual, interpersonal, community, and societal factors. Barriers were coded and grouped into overarching themes that aligned with these levels, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the structural, cultural, and personal challenges faced by ethnic minority women in engaging in PA.

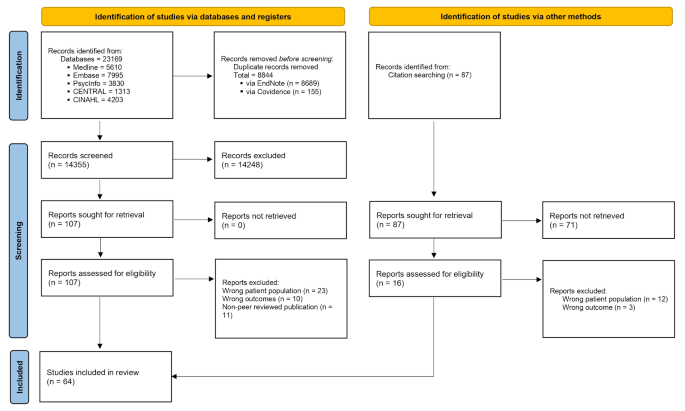

The initial database search retrieved 23,169 records, with 87 additional studies identified through a snowball hand-search. After title and abstract screening, 123 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Ultimately, 64 studies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81], all published in English, met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram, outlining the search process, reasons for exclusion, and final study selection.

Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of the included studies, which were published between 1998 and 2024. The studies utilized diverse research methodologies, including qualitative (n = 55; 85.9%) [18,19,20,21,22,23, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, 40, 41, 44, 45, 47, 49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63, 65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78, 80, 81], quantitative (n = 5; 7.8%) [24, 39, 42, 43, 48], and mixed methods approaches (n = 4; 6.3%) [38, 46, 64, 79]. Among the qualitative studies, data collection methods included focus group discussions, individual interviews, and online forums, with 31 studies (56.4%) using focus groups [18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 26, 28,29,30,31,32, 36, 37, 40, 41, 49, 50, 53, 54, 56,57,58,59, 61, 62, 70, 73, 75,76,77,78], 22 studies (40.0%) using interviews [20, 25, 27, 33,34,35, 44, 45, 47, 51, 52, 60, 63, 65,66,67,68,69, 71, 74, 81], 2 studies (3.6%) utilizing online forums [55, 72]. For the quantitative studies, data were primarily gathered through structured surveys [24, 39, 42, 43, 48]. Details on the specific survey instruments used, including validated scales or researcher-designed questionnaires, are provided in Table 1. In the four mixed-methods studies, the data was collected with interviews and questionnaires [38, 46, 64, 79].

The review included a total of 5,555 women. Sample sizes across the included studies ranged from 4 to 1,398 participants (Table 1). The studies were conducted across 12 countries, including United States of America (USA; n = 31 studies) [19,20,21,22, 24, 27, 31, 33, 36,37,38,39, 41, 43, 44, 48,49,50, 57, 58, 61,62,63, 67, 70, 72, 75, 77, 79], Australia (n = 8 studies) [28, 30, 32, 42, 45, 53, 54, 56], Canada (n = 6 studies) [18, 25, 29, 35, 65, 81], United Kingdom (n = 5 studies) [40, 46, 64, 68, 80], Sweden (n = 4 studies) [26, 59, 66, 73], and New Zealand (n = 3 studies). Bangladesh [60], Spain [47], South Korea [34], Netherlands [23], Singapore [74], Israel [78], and Norway [69] each had one study included.

Ethnic minority status was defined differently across studies. Some explicitly categorized participants as first-generation (n = 30 studies; 48.9%) [19, 21, 25, 26–27, 32, 34,35,36,37,38, 40, 42, 53, 54, 56, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65, 67, 69, 71, 73, 77, 79, 80] or second-generation immigrants (n = 1 study; 1.6%) [23], while others included both first- and second-generation individuals (n = 11 studies; 17.2%) [24, 28, 45, 47, 49, 51, 52, 55, 68, 72, 81]. Several studies did not clearly specify immigration generational status (n = 22 studies; 32.3%) [18, 20, 22, 29,30,31, 33, 39, 41, 43, 44, 46, 48, 50, 57, 58, 66, 70, 74,75,76, 78]. The studies included ethnic minorities (often more than one per study) from all WHO Regions [81], South-East Asia Region (n = 24) [21, 22, 25, 27, 29, 30, 34, 35, 40, 46, 51, 52, 53, 56, 57, 59, 60, 64, 65, 68, 72, 74, 77, 79], Americas Region (n = 21) [19, 20, 24, 26, 31, 33, 36,37,38, 43, 48,49,50, 55, 58, 62, 63, 70, 75, 76, 81], Eastern Mediterranean Region (n = 21) [18, 22, 23, 26, 28, 32, 40, 41, 45, 46, 47, 52, 54, 56, 59, 61, 69, 71, 73, 76, 80], European Region (n = 11) [23, 26, 32, 39, 44, 46, 56, 59, 62, 66, 78], Western Pacific Region (n = 9) [32, 45, 52, 56, 67, 68, 72, 74, 76] and Africa Region (n = 6) [18, 32, 42, 46, 56, 76].

The majority of the studies (n = 40, 62.5%) were classified as high quality (i.e., MMAS ≥ 4) [18, 19, 21,22,23, 25, 27, 30, 31, 33,34,35,36,37, 39, 42, 45, 47, 50,51,52,53, 55, 58, 59, 61, 63, 64, 66,67,68,69,70, 72, 73, 76, 78,79,80,81]. Three studies (4.7%) [38, 48, 62] were classified as poor quality. Details about quality appraisal are available the Supplementary Material 2.

In total, 16 barriers to PA in women from ethnic minority groups were identified and grouped based on the SE framework (Fig. 2). The most common barriers across the included studies were culture, family responsibilities and time. The main barriers faced by ethnic minorities vary by region: in Africa, the most common barriers were culture, family responsibilities, and physical conditions; in the Americas, culture, time, and family responsibilities; in the Eastern Mediterranean region, culture, environment, and misconceptions; in Europe, misconceptions, environment, and culture; in the Southeast Asia, culture, family responsibilities, and environment; and in the Western Pacific, culture, physical conditions, and knowledge. Table 2 shows detailed PA barriers categorized by ethnic minority groups from across all WHO regions.

Barriers to physical activity in women from ethnic minority groups grouped based on the social-ecological framework. PA, physical activity

Based on the SE framework, the intrapersonal barriers identified in this study include time, motivation and interest, physical condition, competing priorities, knowledge, and misconception. Time emerged as a significant barrier due to work responsibilities, family obligations, domestic duties, and competing roles, all of which limit individuals’ availability for PA.

“When we came to Canada […] we needed time to redirect our thinking, restore our calculations, find a job, get credentials evaluated, and find relatives and friends […] It is huge stress that, for sure, affects us!” [18].

“We want to be able to work out regularly. We are too busy doing cooking, making fresh chapati, cleaning and taking care of the family needs and there is no time for exercise.” [21].

“There is not enough time in the day and then by the time I’ve done everything I just can’t be bothered by the end of it.” [28].

Motivation and interest were affected by factors such as low self-discipline, lack of willpower, and low self-efficacy, reducing engagement in exercise. Mental health burnout also was reported to decrease motivation as anxiety, stress and tiredness.

“I just think one of the main points is that we have abnormal circumstances (due to post-war stress and post-war trauma). We are not coping good now.” [32].

“Our circumstances have made us more depressed [than Australian women]. If you are depressed, you are not able to socialize.” [32].

“I think I really detest exercising […] I don’t do it at all. To me, that’s just no fun I can’t do it in the gym. It gets too boring. I find all other sports boring and uninteresting.” [24].

Physical condition, including pain, fatigue, excessive tiredness, health concerns, aging-related decline, and weight issues, also hindered participation in PA. Some individuals reported that their physical condition prevented them from following PA recommendations, which they felt were not adequately tailored to accommodate older women.

“Five minutes is a long time, even a minute is very long so to do 30 minutes is a long, long time for some people.” [64].

“But I have so much stiffness, it is very difficult to do exercise.” [22].

“When it beats that fast you wonder, oh, why is it beating so fast, am I sick, is something happening? Then when it calms down and beats slower it feels easier again.” [26].

Additionally, limited social support - such as a lack of shared responsibilities at home or assistance with daily tasks - was noted as a barrier, as it contributed to time constraints and reduced opportunities to engage in PA. Many individuals reported feeling unsupported in their efforts, including limited encouragement from family and friends, which further reduced their motivation.

“I put my children first. I would never be able to tell my family ‘Take responsibility’ because I need time for myself […] that’s not me. They need me I put myself to the side and then I’ll make time for myself.” [50].

“I think that for Latino women the family is very important, and I think that it is more important for us to take care of the kids than to exercise. The family is more important than exercise.” [58].

“I need to do the housework, take children to school, cook, everything for my family. No time for activities for me.” [56].

Lack of knowledge about PA and related to its availability in the neighborhood was a barrier once individuals were uncertain about which activities they can perform, if its correct or not, and to be physically active. They were also unaware of available incentives or community programs, and unsure on how to engage in sports.

“When it comes to real life, we do not have basic or important knowledge about how to do exercise, we just lay on the mat and pull our legs up and down.” [53].

“I didn’t know how to walk in snow, I didn’t know what snow boots were and my principal was so good; she took me to buy my first winter boots. And then I didn’t know how to walk in snow – I tried so many times.” [35].

“I can do beginners’ aerobics, and it may not do a thing for me. I may need to concentrate on leg exercises or something.” [44].

Lastly, misconceptions such as the fear of gaining excessive muscle and appearing unfeminine, concerns about injury or health risks, feeling too old or physically inadequate, or believing they already engage in enough PA, prevented women from participating in PA.

“I think ladies, they feel like they are doing household work, so it is exercise, and they do not need to do anything extra.” [22].

“To get dressed and walk alone I see as the most boring thing ever!” [73].

“They will say you don’t need to work out if you are so skinny. You are underweight. You don’t need to go to the gym.” [22].

Interpersonal barriers to PA were identified as family responsibilities, language barriers, lack of social support, and social isolation. Family responsibilities played a significant role; the burden of parenting, household duties, and caregiving responsibilities - whether for children, aging parents, or other dependents - restricted opportunities for PA. The lack of childcare and the demands of caregiving were particularly challenging for individuals with large families or those living in multigenerational households, where caring for relatives with chronic illnesses or elderly family members further limited time and flexibility to engage in physical activity.

“If I go spend an hour at the gym (I would love to go), I feel I am robbing time from my children.” [36].

“But here in terms of exercise, you are always cleaning […] there isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t clean and if it is not at home it is at work.” [19].

“My aunt said that ‘You have to do house chores like cleaning, cooking. That will be gym for you. That is the best exercise’.” [22].

Language barriers also emerged as a challenge, with individuals facing difficulties due to a lack of proficiency in the idiom of the new country, which hindered their ability to access PA programs or engage in community activities.

Additionally, lack of social support to incentive, to share the responsibilities or to accompany in the PA. Many individuals reported feeling unsupported in their efforts to engage in PA, including limited encouragement from family and friends, which reduced their motivation.

“Whenever I ask him to go for a walk [with] me, he does not want to and then I don’t feel like going either.” [77].

“[What I need for physical activity is] someone to share in the responsibilities. Because I am always having to work, or running to get someone, or fixing a car, or help[ing] a relative, or clean[ing the] house, I do not have time for anything else.” [55].

Finally, social isolation emerged as a barrier, as individuals felt disconnected from their communities or without a workout companion were less likely to engage in PA.

Barriers to PA identified in the community level include work, acculturation, cultural barriers, and cost. Work was considered a constraint, as many individuals reported feeling too tired, stressed, or busy due to demanding jobs. Some perceived their physically demanding occupations as sufficient for maintaining activity levels, reducing the need for additional engagement in PA.

“I work Monday to Friday and upon coming home I have to do cooking and cleaning. So, practically, I don’t get any time to look after myself and do exercise.” [65].

“My job forces me to stay sitting and makes it difficult to leave my place. It’s not like a 9 to 5 job where we can use our lunch hours. It can go up to 14 hours at a time. It’s because my job requires that I sit and look into the microscopes all day.” [27].

Acculturation posed barriers as individuals adapted to a new reality where walking was uncommon due to societal norms favoring car usage, leading them to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle. Additionally, migration-related stress, post-war trauma, and the necessity of working - when it was not previously required—further limited their opportunities for PA.

“In Latin America, sports such as volleyball are practiced all the time [by women]. However, most of the women don’t work. Here is the US, where the women work, it is mostly kids or husbands who play sports, and the women watch.” [36].

“Here, we work harder than in Haiti. When you have a child, we have to work, to take care of the child, and to do everything. In Haiti, I had a child but I had people to take care of everything.” [19].

“I arrived in a country where there were more important matters for me to be concerned with, such as finding a suitable place to live and a decent job so that I can bring my children up in a suitable environment […] I stopped thinking about myself and taking care of my health.” [80].

Cultural barriers played a significant role in limiting opportunities for PA. In some cultures, PA is not traditionally seen as appropriate for women, and they receive little to no encouragement to participate from an early age. Gender norms and modesty expectations, including the wearing of hijabs and culturally appropriate clothing, were cited as barriers, particularly when accessing mixed-gender facilities. Additionally, religious obligations such as Ramadan, other faith-based commitments, and the absence of gender-exclusive spaces further restricted opportunities, reinforcing cultural norms that discourage women’s participation in PA.

“[My] biggest issue is that I was not exposed to sports growing up due to my gender. [There was a] lack of opportunities for women. My mother discouraged physical activity, but I have participated as an adult. I was not encouraged to be physical[ly] active as a child because I am a woman.” [55].

“Religious festivals make it difficult as we tend to fast. We feel weak and we can’t drink, so it’s no good to exercise.” [40].

“I used to [go] but I don’t like the music because it’s not allowed in the religion.” [64].

Finally, cost of gym memberships, activity fees, and economic instability made PA less accessible cost related to physical activity participation were another barrier.

“Even if [she] had extra money to invest in a gym membership [for herself],” she would “rather buy something for [her] children.” [70].

“Whatever indoor activity you do, it costs you money. That is a constraint.” [51].

“I think you need something like - what they call the personnel at the gym, but sometimes they are expensive, so we don’t.” [63].

Environmental level barriers to PA include environmental constraints. These barriers were influenced by the lack of accessible, exercise-friendly spaces such as sidewalks, parks, or recreational facilities, as well as limited opportunities for engagement. Additionally, poor sanitary conditions in some neighborhoods and safety concerns further restricted participation.

“We have a shortage of places to hang out. We must travel far and away from where we live.” [78].

“Here you can’t go running around the track at the public schools. They won’t give you permission, or the police will give you a ticket and will ask you to leave, or they will be closed.” [58].

“The problem is there is no sidewalk. You’re always afraid of the cars…as you can see there’s some trash on the sidewalk. There’s a signature of a gang or signs of a gang signs on the street. It’s not clean…it’s not safe…for walking, it’s not safe, because it’s…because of the gang signs, she doesn’t feel safe walking here.” [61].

Weather conditions were also identified as environmental barriers, such as extreme temperatures and poor air quality, which reduced motivation and the ability to engage in PA.

“It is winter and it’s too cold to walk, and it’s dark” [73].

“Both climate and periods of darkness have an effect on me, because during the summer I am active. /…/ we can go for a walk at nine o’clock in the evening but when it is winter and it is six o’clock I don’t want to go out, I don’t have any motivation.” [66].

“I think weather also had some impact. The condition of the air after the wildfire was terrible and then it began to rain.” [27].

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to comprehensively examine the barriers to PA among women from ethnic minority groups, offering critical insights into the multifaceted factors limiting their engagement. Understanding these barriers is especially important, as ethnic minority women are at a disproportionately higher risk of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, which are exacerbated by physical inactivity [82, 83]. Studies have consistently shown that women from these groups face significant health disparities due to limited access to healthcare, lower socioeconomic status, and cultural norms that discourage participation in PA [12, 84, 85]. This review, based on 63 studies, provides a comprehensive understanding of how these factors play out across different regions, reinforcing the need for targeted interventions. The use of the SE framework allowed us to categorize barriers into intrapersonal, interpersonal, community, and environmental levels, a model that has been widely supported in public health research as it reflects the complex interplay of individual, social, and environmental factors in influencing health behaviors [86]. This holistic approach is critical, as it enables a deeper exploration of how these different levels of influence converge to either promote or hinder PA participation among ethnic minority women.

In total, 16 barriers to PA were identified across the 63 studies, illustrating the diverse challenges faced by ethnic minority women globally. These barriers spanned the individual level (such as lack of motivation or knowledge about PA), social influences (family responsibilities, cultural expectations), community-level challenges (lack of safe spaces for exercise, cultural mistrust in healthcare), and broader environmental factors (poor access to exercise facilities, unsafe neighborhoods). Previous research highlights that these multi-level barriers are often interconnected and compound each other, making it difficult for women to engage in PA even if they are motivated to do so [87, 88]. A notable strength of our review is the identification of both universal and region-specific barriers, shedding light on how cultural, economic, and geographic factors shape women’s experiences and opportunities for PA. This segmentation of barriers by region provides essential context for understanding the global and localized challenges faced by these women, allowing for more nuanced recommendations for intervention.

The findings reveal that while some barriers, such as cultural factors, family responsibilities, and time constraints, were consistently reported across ethnic minorities from all WHO regions, there were notable differences in the specific nature of these barriers depending on the geographic and socio-cultural contexts of the ethnic minority groups. For instance, studies involving participants from African immigrant communities often highlighted the centrality of cultural norms and family responsibilities as primary barriers to PA participation. Research has shown that in many African cultures, gender roles and familial expectations limit women’s autonomy [89], which directly impacts their ability to engage in physical activity. Similarly, studies from immigrant women in the Americas found that time constraints, particularly due to work and family duties, were the most significant obstacles to PA. Time poverty, especially among women with caregiving responsibilities, has been widely documented as a key barrier to women’s health in both high- and low-income settings [90]. The results from immigrant populations from the Eastern Mediterranean region, where environmental factors and misconceptions about PA were identified, echo findings from previous studies that show how misconceptions regarding exercise - such as beliefs that PA is unnecessary for older adults or that certain exercises are inappropriate for women - can discourage participation in PA programs [9]. Studies with ethnic minorities from European countries highlight misconceptions and environmental factors, such as limited access to safe exercise spaces, as major barriers to physical activity, which aligns with findings from disadvantaged populations facing similar challenges [91, 92]. Southeast Asia presented family responsibilities and environmental factors as key challenges, which mirrors research showing that competing familial demands are consistent barriers to PA in these groups [10, 93]. In the Western Pacific, cultural issues, physical conditions, and knowledge deficits were the most commonly reported barriers, consistent with studies that highlight how lack of knowledge about PA benefits, coupled with cultural stigmas regarding women’s physical appearance or modesty, can hinder participation in exercise [9, 94].

These findings underline the complexity and regional variation of barriers to PA among ethnic minority women. Although personal barriers such as lack of time, motivation, and knowledge are frequently reported across regions, the role of structural and cultural factors is equally important in shaping PA behaviors. Previous research has emphasized that while individual motivation can influence PA, these personal factors are often overshadowed by structural and cultural constraints that limit opportunities for being active [95, 96]. For example, societal expectations around caregiving and domestic responsibilities are frequently cited as barriers, with women often prioritizing family needs over their own health [97]. These responsibilities include not only childcare but also the care of aging parents or other family members, which is particularly common in multigenerational households. This points to the necessity of interventions that go beyond individual-level approaches and incorporate strategies to address the broader structural and cultural challenges that these women face. Additionally, misconceptions about exercise and its benefits, along with competing priorities like family duties and work obligations, were consistent barriers across multiple regions. These findings support calls for public health campaigns aimed at correcting misconceptions about PA, emphasizing its importance for women’s health, and integrating these messages into culturally relevant educational programs [98, 99].

In light of these findings, it is essential to consider the intersectionality of barriers and how they might overlap or compound in the lives of ethnic minority women. Intersectionality, a concept widely used in health disparities research, helps explain how multiple factors - such as race, gender, socioeconomic status, and cultural context - interact to create unique health challenges for these women [100]. For instance, low income and limited access to safe spaces for exercise were frequently identified as additional barriers, especially in low-resource settings. These factors disproportionately affect ethnic minority women, particularly in marginalized communities where resources are scarce, and access to healthcare and exercise facilities is limited [101]. The intersection of these barriers often results in compounded disadvantages, making it even more challenging for women to engage in PA. This highlights the need for interventions that are not only culturally competent but also consider socioeconomic factors and address systemic issues, such as poverty and access to safe exercise spaces, that contribute to physical inactivity [102, 103]. Moreover, the variability of barriers across regions calls for region-specific strategies that are responsive to the unique cultural, economic, and environmental factors influencing PA participation. Tailoring interventions to the local context is crucial to ensuring their effectiveness in overcoming the barriers identified in this review.

Analysis of the barriers to physical activity among ethnic minority women highlights key implications to promote physical activity among ethnic minority women. These implications pertain to: (1) providing women-only spaces or culturally appropriate attire options to encourage participation [104]; (2) multilingual resources to address language barriers, ensuring that information about physical activity is both accessible and culturally relevant [105]; (3) offering family-friendly exercise programs or childcare support to facilitate engagement; and, (4) prioritizing safety concerns, particularly for women in communities with limited access to safe recreational spaces [106], by advocating for improved infrastructure, such as well-maintained sidewalks and accessible parks. By incorporating these considerations into practice, clinicians, policymakers, and public health professionals can help bridge existing disparities and enhance physical activity participation among ethnic minority women.

This review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, location-specific factors and citizenship status differences must be considered, as the barriers faced by ethnic minority groups can vary across countries, regions, and immigration contexts, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Second, the broad age range of included participants may have limited our ability to examine age-specific barriers in depth [107]. Future studies could focus on specific age groups, such as women of childbearing age, to explore more targeted challenges and facilitators. Third, the exclusion of studies focusing on women with specific health conditions (e.g., cancer, osteoarthritis, pregnancy, type II diabetes) may have overlooked important barriers faced by ethnic minority groups within these populations. Finally, gaps in the literature remain, as there is a lack of randomized controlled trials evaluating interventions specifically targeting ethnic minority women. Future research should prioritize high-quality, intervention-based studies to better understand how to effectively address the barriers identified in this review. Additionally, more research is needed to explore how mental health challenges intersect with cultural and structural barriers to limit physical activity engagement among minority women [108].

In conclusion, this review highlights the multifaceted barriers to PA participation among ethnic minority women, providing a comprehensive understanding of the factors that limit their engagement. Through the synthesis of 64 studies, barriers were classified into intrapersonal, interpersonal, community, and environmental categories. Our findings emphasize the dominance of intrapersonal factors, such as time constraints, motivation, misconceptions, and competing priorities, in shaping physical activity behaviors. Interventions should thus focus on empowering individuals to overcome these challenges, particularly through health education programs that emphasize the importance and benefits of physical activity, helping individuals reframe perceptions, increase motivation, and develop strategies for managing time constraints. Additionally, this review underscores the importance of a regionally tailored, culturally competent approach to promoting PA among women from ethnic minority groups. While barriers identified in this study are widespread, they vary significantly across regions, cultures, and citizenship statuses, highlighting the need for interventions that are sensitive to these differences. Previous literature suggests that culturally tailored interventions, which consider local barriers, have been more successful in increasing PA levels among ethnic minority women. This study provides valuable insights into global and regional variations, offering important implications for public health policy and intervention design. By addressing both individual and structural factors, it is possible to promote greater PA participation and improve health outcomes for ethnic minority women worldwide, reducing the risk of chronic diseases linked to physical inactivity.

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Batalha, A.P.D.B., Marcal, I.R., Main, E. et al. Barriers to physical activity in women from ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. BMC Women's Health 25, 330 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-025-03877-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-025-03877-y