BMC Women's Health volume 25, Article number: 293 (2025) Cite this article

AbstractSection Introduction

Gestational diabetes is a common problem among pregnant women that can lead to many complications for the mothers and their fetuses. Gestational diabetes self-care can reduce the consequences and outcomes of this disease. Some of the factors related to self-care of gestational diabetes are quality of life, social support, and domestic violence. This study aims to investigate the relationship between quality of life, perceived social support, and domestic violence with gestational diabetes self-care using structural equation modeling.

AbstractSection Method

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 400 pregnant women with gestational diabetes from April 22, 2023, to July 6, 2023, in Tehran using convenience sampling. Data were collected using demographics, domestic violence, perceived social support, quality of life, and gestational diabetes self-care questionnaires. After data collection, data analysis was performed using SPSS-21 and Lisrel-8 software.

AbstractSection Results

According to the results obtained from structural equation modeling, among the variables that were related to gestational diabetes self-care, quality of life (B = 0.86) in the direct path and perceived social support (B = 0.48) in the indirect path had the highest positive relationship with gestational diabetes self-care. Domestic violence was the only variable that had no relationship with gestational diabetes self-care in any of the paths.

AbstractSection Conclusion

According to the path analysis, gestational diabetes self-care is directly influenced by perceived quality of life but perceived social support is indirectly positively related to the impact on quality of life with gestational diabetes self-care. Therefore, it is recommended that actions and strategies be adopted to improve the quality of life and increase perceived social support in this vulnerable group.

A common type of diabetes is gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), with onset or first recognition during pregnancy [1]. The prevalence of GDM has been reported to be 15 to 20% worldwide [2] and has reached 18.6% in Iran [3]. Gestational diabetes is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes for the mother and the baby [4]. Various maternal complications may occur with gestational diabetes, such as high blood pressure and persistent insulin resistance after delivery, and long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and chronic type 2 diabetes in later stages of life [5, 6]. In addition, mothers with gestational diabetes are at higher risk for preterm delivery and low birth weight babies in subsequent pregnancies [7]. At the neonatal level, gestational diabetes causes hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, respiratory distress, shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, and macrosomia [7, 8]. Also, the increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes can cause economic and social health burdens at the public and individual levels [9].

Given the increasing prevalence, complications, and economic burden on mothers, children, and the health care system, management of diabetes in pregnancy is essential [10].

The World Health Organization defines self-care as the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with disease and disability with or without the support of a healthcare provider [11].

Self-care for diabetes is complex and requires management of medication regimens (taking the appropriate dose of medication at the right time), adherence to a suitable diabetic diet to stabilize blood glucose levels and choose healthy foods, blood glucose monitoring, regular exercise and regular attendance at medical visits to maintain optimal blood glucose control [12]. In diabetes, adherence to self-care behaviors determines the effectiveness of management and control of blood sugar [13]. Empowerment strategies for self-care behaviors among mothers with gestational diabetes led to increased adherence to diet, medication use, physical activity, and blood glucose monitoring; increased blood sugar control; reduced cesarean delivery and macrosomia; and reduced infant hospitalization rate [14,15,16].

Various factors can affect self-care for gestational diabetes during pregnancy, such as perceived social support, quality of life, and domestic violence [17,18,19]. For example, mothers with gestational diabetes reported a need for support from healthcare providers and families to participate in and adhere to self-care activities [20, 21]. Also, a study conducted in Indonesia showed a positive and significant relationship between self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes and quality of life [17]. In addition, another factor that can affect self-care is domestic violence. IPV has negative consequences for women’s physical and mental health. For example, depression caused by IPV can affect women’s ability to care for themselves [18].

Most studies on the factors affecting gestational diabetes self-care have evaluated simple linear relationships between variables, but none have examined all the variables in one model. Although these studies have sought the relationship between self-care for diabetes and some variables, more studies are needed to clarify the relationship between multiple factors and gestational diabetes self-care and the percentage of changes in self-care predicted by independent variables.

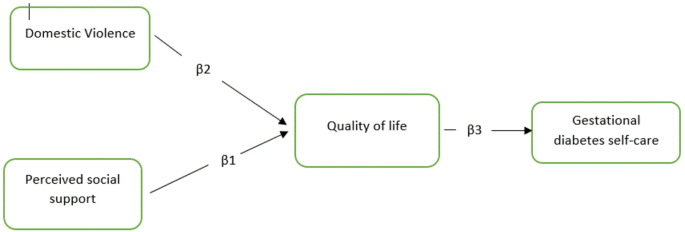

According to the WHO’s conceptual framework regarding the Commission on Social Determinants, there are two main categories of structural determinants: (a) the socioeconomic and political context, and (b) various other factors such as education, income, gender, race, ethnicity, and employment status, which result in diverse and unequal socioeconomic groups, ultimately defining an individual’s social class; 2. The intermediary determinants of health comprise behaviors and psychosocial factors such as social support, quality of life, and domestic violence [22]. Intermediary health determinants, whether individually or through their interactions, strongly influence overall health status [22]. Based on the WHO model gestational diabetes self-care is considered as the health outcome and considering that various studies have rarely addressed it and it’s affecting factors, and considering the importance of this issue, the following hypothetical model was proposed and its fit was determined (Fig. 1).

The design of the current study was a cross-sectional study (Cross-sectional study design is a type of observational study design. In a cross-sectional study, the investigator measures the outcome and the exposures in the study participants at the same time) which was conducted on 400 Iranian pregnant women with gestational diabetes who were referred to comprehensive health centers of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences from April 22, 2023, to July 6.

Considering the prevalence of gestational diabetes in Iran (18.6%) [3] the error of 0.04 and the confidence interval of 95%, taking into account the 10% drop of samples, the sample size was calculated to be 400 people according to the following formula.”

$$n = {{\mathop z\nolimits_{1 - {\alpha \over 2}}^2 p\left( {1 - p} \right)} \over {{d^2}}}$$

In studies that use structural equation modeling, due to the multivariate nature and the complexity of the relationships between the variables, there is no specific formula for calculating the sample size. The minimum sample size required for the structural equation is 200 [19]. Also, the results of simulated studies have shown that it is better to consider 20–30 samples for each parameter in the study [23]. Considering that there were 15 parameters in the present study, 24 samples were considered for each parameter, and considering the possibility of a 10% dropout of samples, the final sample size was calculated to be 400 people.

Sampling was done by convenience until the sample size was completed among the eligible ones. The information about pregnant women with gestational diabetes and referred to the health centers of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences was obtained from the center officials and by contacting these people and explaining the study and its objectives, they were asked to refer to the centers to complete the questionnaires.”

Married women pregnant between 18 and 45 years old, having at least literacy reading and writing, no history of mental illness or any known physical illness in pregnancy (according to the person’s own words or recorded in the file), gestational age over 24 weeks.

Age under 18 years, multiple pregnancies, and suffering from other chronic diseases (Cardiovascular diseases, high blood pressure, pulmonary and respiratory diseases, history of glucose tolerance disorder) before pregnancy or during pregnancy.”

Information was collected through demographic and obstetric questionnaires, perceived social support by Zimet and colleagues, the World Health Organization’s domestic violence questionnaire, the World Health Organization’s quality of life questionnaire, and gestational diabetes self-care behaviors.

It includes questions about the mother’s age, spouse’s age, ethnicity, gestational age, number of pregnancies, number of children, number of abortions, number of stillbirths, and history of cesarean section.

The World Health Organization screening tool is valid for screening domestic violence in three physical, psychological, and sexual domains. Physical violence is assessed with 9 questions, sexual violence with 8 questions, and emotional violence with 15 questions. In this scale, violence is confirmed by answering positively to any of the questions of the questionnaire on physical, emotional, and sexual violence. The number of cases of domestic violence is measured based on the five-point Likert scale. The internal reliability of this tool using Cronbach’s alpha in three domains was 0.92, 0.89, and 0.88 for physical, psychological, and sexual violence, respectively [24]. Its validity has been assessed in various Iranian studies and has been appropriate [25].

It is a 12-item tool that was developed to assess perceived social support from three sources family, friends, and significant others in life by Zimet and colleagues (1988). Questions 11-8-4-3 measure the source of family, questions 12-9-7-6 measure the source of friends, and questions 10-5-2-1 measure the source of supportive others. The maximum score for each scale is 20 and the minimum is 4. As the scores of individuals increase in each factor, their score in the general factor of social support will increase. Higher scores obtained by individuals indicate a higher level of perceived support. Scores of 20 − 12 indicate low perceived social support, scores of 40 − 20 indicate moderate perceived social support and scores higher than 40 indicate high perceived social support [26].

It is a self-report questionnaire that assesses self-care activities of the dietary regimen (6 questions including questions on the number of days of adherence to the dietary regimen, dividing feeding times throughout the day, consumption of fruits, vegetables, high-fat dairy products, and sweets), physical activity (2 questions including questions on the amount of physical activity and exercise during the week), blood glucose monitoring (3 questions including questions on the number of times blood glucose testing is performed), Proper use of oral medication (1 question), and insulin injection (1 question including the number of times insulin is injected regularly), and smoking (1 question) during the past 7 days. The response to all questions of this questionnaire is based on a three-level Likert scale (0–7). Obtaining a higher score in each domain and the whole questionnaire indicates better self-care [27]. The validity of this questionnaire was confirmed in the study by Kordi and colleagues with the content validity method and its reliability with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.70 [28].

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire 26-item (WHOQOL-BREF) is a 26-item questionnaire that measures the overall and general quality of life of an individual. This scale was developed in 1996 by a group of experts from the World Health Organization by adjusting the items of the 100-item form of this questionnaire. This questionnaire has 4 subscales and one total score. These subscales are physical health, mental health, social relationships, environmental health, and one overall score. Initially, a raw score is obtained for each subscale, which must be converted to a standard score between 0 and 100 using a formula. A higher score indicates a higher quality of life. In Iran, a study was also conducted on 1167 people from Tehran to examine the validity and reliability of this questionnaire. The test-retest reliability for the subscales was as follows: physical health 0.77, mental health 0.77, social relationships 0.75, and environmental health 0.84 [29].

After obtaining permission from the relevant authorities and receiving the ethics code from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with the number IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1402.06, the study began. First, the researcher referred to the selected treatment centers and after identifying the pregnant women eligible to participate in the study, the objectives of the study were explained to them. If they were willing to participate in the study, they were asked to sign a written consent form. Then, the mentioned questionnaires were delivered to them to complete. A separate and quiet room was provided for mothers to complete the questionnaires, and if they did not have the opportunity to complete them on the same day, they were asked to complete and deliver them within a maximum of two weeks by coordinating with the researcher. The researcher’s phone number was given to pregnant mothers to answer any possible questions and ambiguities. Pregnant mothers were also assured that their information would remain confidential and that there was no coercion for participation and cooperation in this study, and if they decided not to participate in this study, they would not face any restrictions or problems. Sampling was done continuously until the sample size was completed.

Data analysis was performed by SPSS software version 21 using descriptive statistics (frequency, mean, standard deviation, and percentage). Also, to examine the relationship between variables with each other, after checking the normal distribution of data using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Spearman correlation test was used. The significance level of p < 0.05 was considered. Then, for designing and fitting the model, the structural equation modeling method and Lisrel-8 software were used. The SEM model was evaluated using the following indices: (TLI > 0.90), (RMSEA > 0.08), (GFI > 0.9), (NFI > 0.9), (CFI > 0.9), and (IFI > 0.9) [30]. SEM, also known as covariance structure modeling, is used to process complex multivariate research data [31].

In the present study, the information of 400 pregnant women referred to the comprehensive health centers of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences who were present until the end of the study was examined. The mean age of pregnant women participating in the study and their spouses was 29.93 ± 5.55 and 34.50 ± 5.55, respectively. The mean gestational age in pregnant mothers participating in the study was 30.52 ± 4.15 and the mean quality of life score was 68.64 ± 18.89, the perceived social support score was 26.45 ± 11.35, the mean domestic violence score was 54.81 ± 19.93 and gestational diabetes self-care score was 3the 6.20 ± 14.85, which indicates a low level of gestational diabetes self-care in pregnant mothers (Table 1).

Based on the results of Pearson correlation test, there was a positive and significant relationship between gestational diabetes self-care and quality of life (r = 0.744, P < 0.001). Also, there was a positive and significant relationship between social support and gestational diabetes self-care (r = 0.397, P < 0.001). This means that with the improvement of quality of life and social support, the level of gestational diabetes self-care will increase and vice versa. However, there was no significant relationship between gestational diabetes self-care and domestic violence (r=-0.081, p = 0.111) (Table 2).

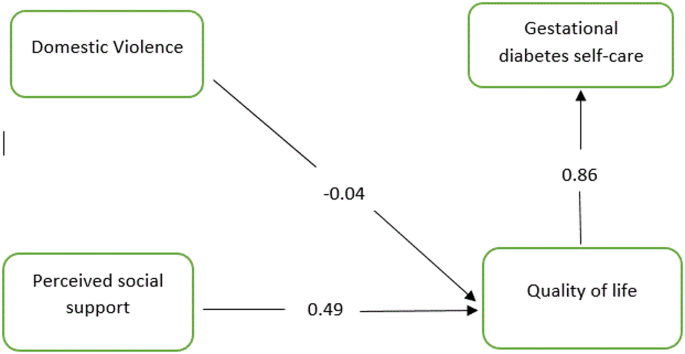

Based on the results of structural equation modeling, among these variables, quality of life only has a direct relationship with gestational diabetes self-care (B = 0.86, P < 0.001) and social support also has an indirect relationship with gestational diabetes self-care through the effect on quality of life (B = 0.49, P < 0.001). However, domestic violence is the only variable that has no relationship with gestational diabetes self-care through any of the paths (B = 0.03, P < 0.43). (Table 3) (Fig. 2). The following indicators showed that the hypothetical model fit the data well: χ2 /df = 1.957, TLI = 0.96, IFI = 0.97, NFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.078, GFI = 0.91.

Path analysis test of the relationship between the perceived social support, domestic violence, and quality of life with gestational diabetes self-care in pregnant women

This study explored the ways by which perceived social support, quality of life, and domestic violence affected gestational diabetes self-care in pregnant women. Based on the results of structural equation modeling, quality of life had only a direct positive relationship with gestational diabetes self-care, which is consistent with other studies that were conducted on patients with type 2 diabetes [32, 33]. Perceived low quality of life can seriously interfere with daily diabetes self-care and is associated with adverse medical outcomes and high costs [34]. A possible explanation for this relationship is that quality of life interacts with physical and mental health dimensions under the influence of various factors such as economic, social, psychological, and physical abilities [35], which affect the individuals’ abilities in self-care. From a clinical perspective, quality of life is a key criterion for evaluating treatment effectiveness and decision-making [36].

Another study finding was the positive relationship between gestational diabetes self-care and perceived social support through an indirect path mediated by quality of life. This finding is in line with another study conducted by Karimi et al. in 2017 on the relationship between attitude, self-efficacy, social support, and adherence to self-care behavior of diabetes in Iran. They found that diabetic patients with higher self-care scores had better social support and attitudes toward self-care [13]. Marquez et al. showed that social support plays an important role in physical activity and weight loss in diabetic patients [37]. Also, in other studies on different patients, perceived social support had a positive relationship with quality of life [38, 39]. A possible explanation for this finding is that social support creates positive feelings and happiness, helps people cope with stress, provides information and assistance when needed, and creates a sense of value in individuals, which increases their self-esteem and self-efficacy, which can enhance their ability to self-care [40]. Social support plays two important roles in diabetic patients as a psychosocial concept: (1) improving quality of life and self-care behaviors and (2) increasing patient adherence in stressful situations [41, 42].

In our study, there was no relationship between domestic violence and gestational diabetes self-care. According to the reviews, we have not yet surveyed the relationship between these variables. Still, this finding is contrary to other studies that show that intimate partner violence has negative consequences on women’s physical and mental health. For example, depression caused by IPV can affect women’s ability to self-care [18] and reduce their health literacy [43], but a recent study conducted on women with HIV in several African countries showed that women’s experience of intimate partner violence (IPV) is not associated with poor engagement in HIV care and treatment [44], which is line with findings of current study. In addition, the underreporting of domestic violence could be an important factor. Women may refrain from disclosing their experiences for fear of further violence, shame, or social stigma, which could lead to an inaccurate estimate of the true prevalence of domestic violence in the sample. These factors could contribute to the observed lack of a significant association and should be considered in future research examining this complex relationship.

Qualitative studies can provide deeper insights into the personal experiences of women who have experienced domestic violence and help identify the specific barriers and challenges they face in managing their health. These studies can include interviews or focus groups to gather detailed narratives from participants. In addition, prospective studies can be useful in examining how domestic violence affects their care over time and take into account possible changes in levels of violence or support. Longitudinal data can establish clearer cause-and-effect relationships and assess changes in caregiving behaviors following interventions or changes in the family environment.

According to the findings of our study, quality of life and social support are related to gestational diabetes self-care. To improve self-care in vulnerable groups, it is suggested that screening programs be implemented to identify women with gestational diabetes and at low risk of self-care. After identifying them, suitable intervention programs should be carried out to improve the self-care status and reduce the complications of gestational diabetes in these groups of women.

According to our investigations, various studies have not investigated the effect of various factors on gestational diabetes self-care, and the attention of most researchers is focused on type 2 diabetes, this study is one of the few studies that have examined gestational diabetes self-care.

This study also had some limitations that should be considered. The most important limitation of this study was that the data were collected through self-reporting by patients, which means that pregnant mothers may have reported their ability to self-care, perceived social support, perceived quality of life, and domestic violence less or more than the actual level.

This study presented a causal model of the relationship between perceived social support, perceived quality of life, and domestic violence with gestational diabetes self-care in pregnant women. Perceived quality of life and perceived social support can predict the level of gestational diabetes self-care. The most important factor that affects the level of gestational diabetes self-care is perceived quality of life. Also, perceived social support has an indirect effect on the level of self-care but there was no association between IPV and gestational diabetes self-care that should be more assess in the future studies with larger sample size. Therefore, it is suggested that special attention should be paid to these two important factors, namely quality of life and perceived social support, in women with gestational diabetes.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This article was conducted with the help of the respected staff of the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery and the Research Center of the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC. 1402.06) and for this purpose, their efforts and efforts are appreciated and thanked.

This work was supported by the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and the grant number was 1402.06.

All methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations or the declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). This research was approved in the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with the ethic code IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC. 1402.06.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Vakili, F., Mahmoodi, Z., Nasiri, M. et al. Association of intermediate health determinants with gestational diabetes self-care: a structural equation modeling approach. BMC Women's Health 25, 293 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-025-03844-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-025-03844-7