You may also like...

Dr. Ola Orekunrin: Nigerian-British Doctor and Founder of Flying Doctors Nigeria

Meet Dr. Ola Orekunrin, the Nigerian-British doctor who founded Flying Doctors Nigeria, West Africa’s first air ambulanc...

7 Nutritious Breakfasts You Can Make in Under 10 Minutes

Always running late in the morning? These 7 nutritious Nigerian breakfast ideas can be made in under 10 minutes and are ...

’90s Heels That Refused to Stay in the Past: Six Styles Walking Back Into 2026

Six iconic heels from the 1990s are making a stylish return in 2026. From two-tone pumps to transparent heels, here’s ho...

Patience Ozokwor: The Nollywood Legend Who Turned Into a Meme Queen

Patience Ozokwor didn’t just act in Nollywood, she became Nigerian pop culture. From her “Mama G” roles to the memes tha...

Why Is the Keyboard Not Arranged in Alphabetical Order?

Why isn’t your keyboard alphabetical? The surprising history of QWERTY reveals how broken machines, clever hacks, and 19...

The Story Behind Elon Musk’s Record-Breaking xAI–SpaceX Merger

Elon Musk’s $1.25 trillion xAI–SpaceX merger reshapes AI, space, and global tech. Here’s what it means for investors, us...

They Didn't Choose Their Parents: Do Nepo Babies Still Deserve the Blame?

The Nepo vs Lapo debate has taken over Nigerian social media, but is it fair to blame nepo babies for their privilege? T...

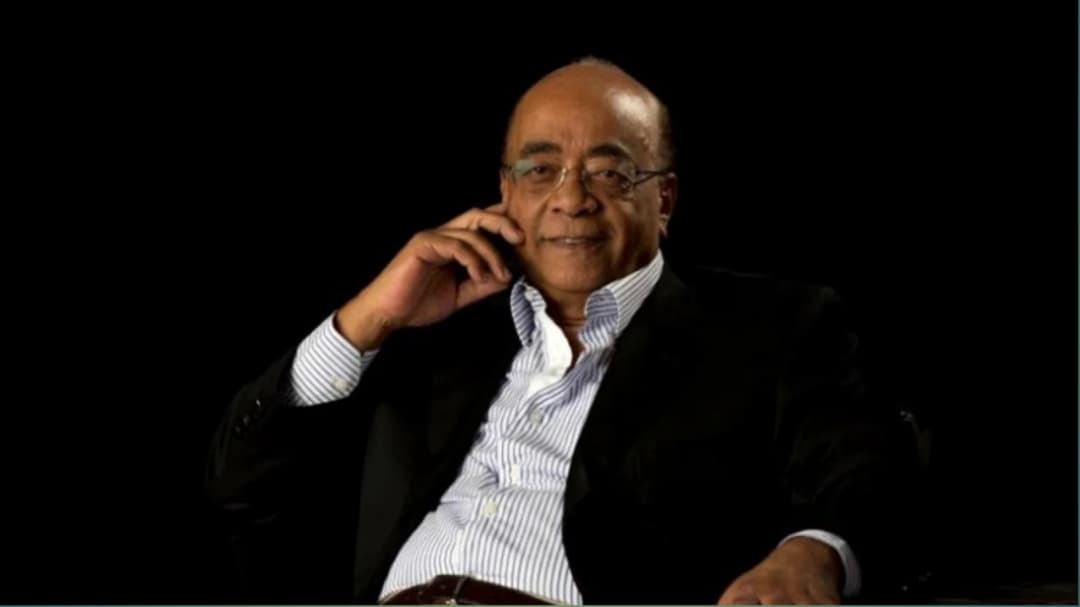

Mo Ibrahim: Africa’s Telecom Tycoon and Champion of Good Leadership

Read the inspiring story of Mo Ibrahim, the African telecom billionaire who built his empire with integrity and now uses...