Black women still lack autonomy over their own bodies

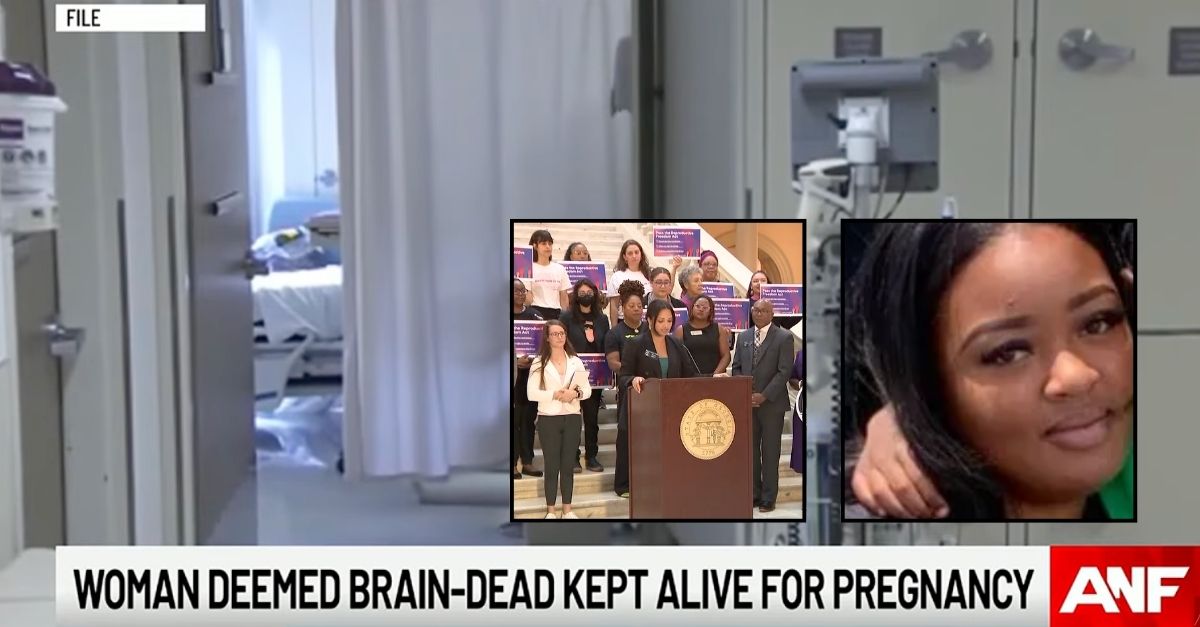

In February, Adriana Smith, a 30-year-old Black woman, started to complain about intense headaches. She went to Northside Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, and was only given medication before being released. According to her mother, the hospital didn’t do any tests or scans. The next morning, her boyfriend woke up to her gasping for air and gargling in her sleep. Upon arriving at Emory University Hospital, where she worked as a nurse, a CT scan revealed multiple blood clots in her brain. She was later declared brain dead.

Smith was nine weeks pregnant. Georgia’s heartbeat law, which bans abortion after six weeks of pregnancy, prevented her family from getting a legal order to turn off the ventilator and allow her to die. It’s a complicated case but Smith must remain on life support to sustain the fetus until she reaches 32 weeks gestation and the baby can be delivered.

Smith, considered medically dead, is now about 25 weeks pregnant. While any woman, regardless of their race, could experience such horrifying repercussions of Georgia’s extreme fetal heartbeat law, this tragedy draws attention once again to the well-documented disparity of medical treatment received by women of color, seen today in such ways as the reality that Black women are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than white women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For many Black women, Smith’s case has resurfaced the repeated and troubling history of Black women not having autonomy over their own bodies.

In the 19th century, Dr. James Marion Sims experimented on enslaved Black women. He performed multiple horrific surgeries without providing pain-reducing medications. He believed, as many still do, that Black people can endure more pain than others. Sims became known as the “Father of Modern Gynecology” and Black women continued to be forced to help modern medicine advance.

Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman from Virginia, entered Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1950s with severe cervical cancer. Without her knowledge, doctors harvested her cells and used them for research due to their ability to constantly reproduce. Her cells, now known as HeLa cells, paved the way for medical breakthroughs such as the polio vaccine, cancer treatments, and more. Yet, for years she went unacknowledged and her family uncompensated for her contributions.

In the 1960s, North Carolina enacted horrendous sterilization laws. These laws were created to prevent children from being born with “undesirable” traits, to stop people from being parents who were deemed “unfit” to raise children, and to control the cost of welfare. Many Black women were forcibly or unknowingly sterilized and stripped of their reproductive rights due to their lack of education and social status.

These women weren’t given a choice when it came to health care decisions. And now, Smith isn’t being given one, either. Georgia’s harsh mandate has stripped yet another Black woman of a choice she or her family should make. The continuing cycle of medical turmoil never seems to end for Black women. Smith is being forced to endure the consequences of choices she didn’t make. She now joins the long list of Black women whose bodies have been used as vehicles for testing medical limits.

Restrictive legislation such as Georgia’s heartbeat law puts the lives of all women at risk. But for Black women who already deal with implicit bias in the health care system despite their income, education, or status, the risks come with even more tragedies.

Christine Wallen is a member of the editorial board. Her opinions are her own.