You may also like...

Samsung Galaxy S26: Everything About the Feb 25 Drop

Samsung’s Galaxy S26 lineup drops February 25, promising smarter AI, stronger safety features, better battery life, and ...

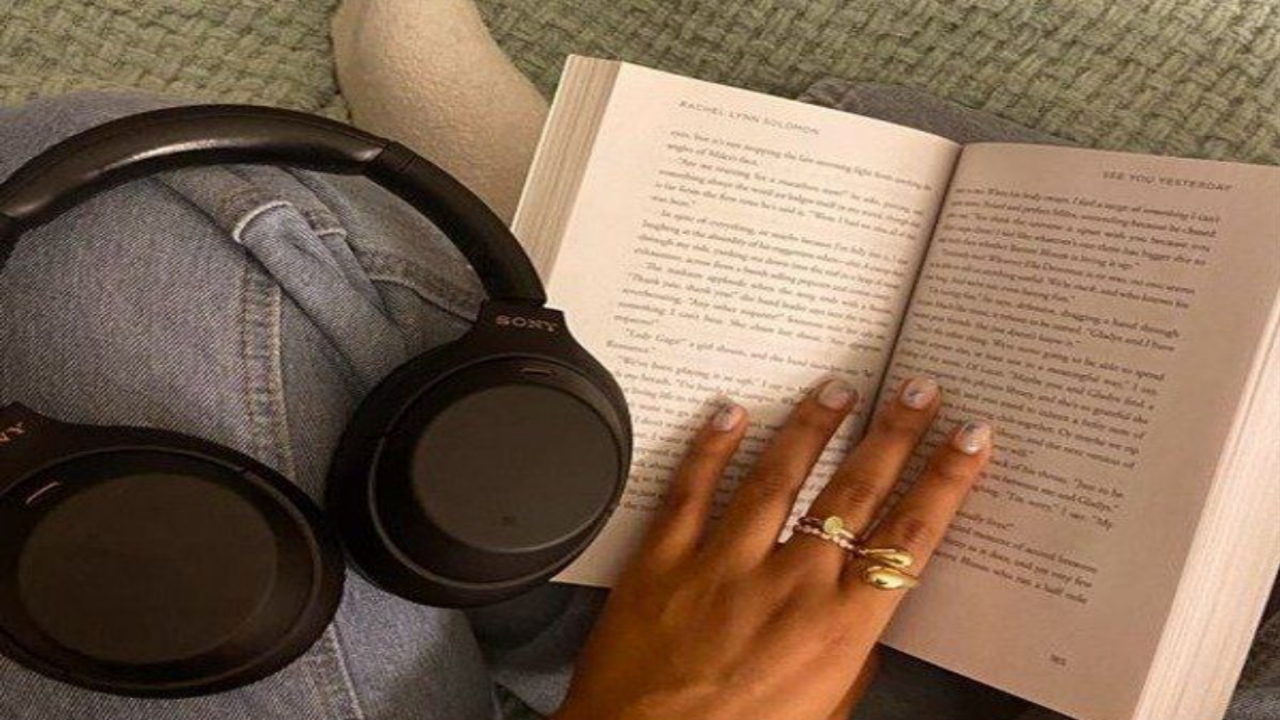

7 Nigerian Books to Read This Season of Love

This season of love deserves stories that feel real. From tender marriages to complicated modern dating, these Nigerian ...

Popular Slangs Used in Nigeria’s Fashion Space

A short piece on Nigerian fashion slangs, their meanings, and how language shapes style, confidence, and expression in ...

The Unique Styles of Some Iconic African Musicians

This article talks about some iconic African musicians that use rhythm, culture, and storytelling to create powerful mus...

Beyond GDP: What Africa’s Most Socially Progressive Countries Tell Us About Real Development

Have you heard of the Global Social Progress Index? This is a deep dive and insight into the 2026 Global Social Progress...

Why More Women Are Choosing Single Motherhood Over Marriage

More women are choosing single motherhood for independence and freedom. Marriage can bring love but also stress, while r...

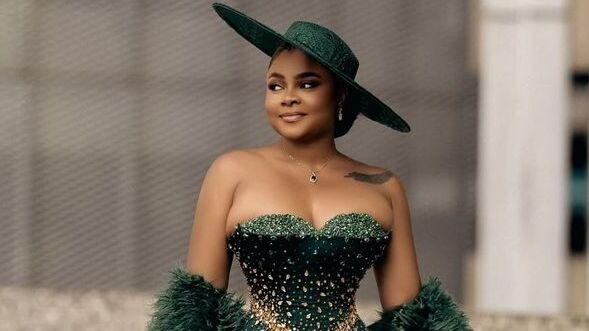

Bimbo Ademoye: The New Face of Nigerian Nollywood Comedy

From Ebute-Meta to the AMVCA stage, Bimbo Ademoye has redefined Nollywood comedy with authenticity, impeccable timing, a...

14 Things to Stop Buying If You’re Serious About Your Financial Goals This Year

Most financial goals fail quietly, not through big mistakes but small daily purchases. These are the everyday things dra...