BMC Medical Education volume 25, Article number: 432 (2025) Cite this article

This study aims to assess social workers’ educational needs in geriatric competencies and their attitudes toward older adults, providing insights for the development of a targeted training program.

This cross-sectional study was conducted with 1,619 social workers. Data were collected using the Geriatric Social Work Competency Scale and the UCLA Geriatric Attitudes Scale and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0. The study received ethics committee approval from the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Ege University (Decision No. 21–5.1T/63, dated May 27, 2021).

The study included 1,619 social workers, of whom 53.8% were women, with a median age of 32 years. The findings from the Geriatric Social Work Competency Scale revealed that social workers’ geriatric competencies were relatively low. A negative correlation was found between age and competency, whereas professional experience, as well as the subscales of values, assessment, and intervention, showed a positive correlation with competency. Additionally, the number of older adults with whom the social workers lived positively influenced their competency. The UCLA Geriatric Attitudes Scale indicated that social workers’ age was negatively correlated with their attitudes toward older adults, while professional experience and participation in in-service training on aging had a positive effect on their attitudes.

This study emphasizes the importance of developing a specialized training program to enhance social workers’ geriatric competencies and attitudes toward older adults. Key factors such as age, professional experience, in-service training, and personal interactions with older adults significantly influence social workers’ effectiveness. Tailored training initiatives that focus on geriatric knowledge, positive attitudes, and practical skills will better equip social workers to meet the demands of an aging society.

The proportion of older adults in the general population is increasing every day. According to TUIK (Turkish Statistical Institute) 2023 data, the rate of older adults in Türkiye rose from 8.8% to 10.2% over the last five years, representing a 21.4% increase. This growth, expressed in both numbers and percentages, underscores not only the heightened need for social workers in quantitative terms but also the importance of professional qualifications. As technology advances and the quality of life and care improves, older adults and their relatives are increasingly demanding higher-quality social services. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the necessary competencies, address any deficiencies, and train qualified professionals in order to improve service quality.

Social work departments in Turkish universities currently offer gerontology as an elective course. However, the exact level of geriatric competency among alumni from these departments remains unknown. Given the increasing importance of old age as a core component of social work, gerontology should be included as a mandatory course in the curriculum. To date, no training programs have been conducted to enhance social workers’ geriatric knowledge and skills, nor have their specific needs in this area been determined.

Although there are only a few social workers in Türkiye who work in geriatric units—whether independent or affiliated with internal medicine departments—those in hospitals where such units exist provide services to older adults after consultation. Social workers receive no formal training on aging, except for the undergraduate elective course Social Work with Older People.

The aim of this study is to assess the current situation and needs of social workers in order to develop an educational program on older adults specifically tailored for them.

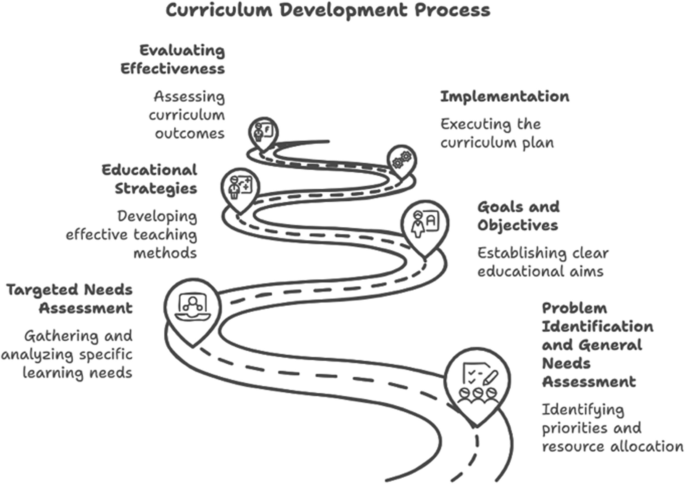

Program development encompasses the dynamic relationships among the objectives, content, teaching–learning process, and evaluation elements of the curriculum. Kern et al. (2015) described a comprehensive program development process consisting of six basic steps [1], as shown in Fig. 1.

Problem identification and general needs assessment: This process provides a rational approach to identifying priorities and utilizing available resources, and it includes gathering and analyzing information on the learning needs of the target group [1]. A wide variety of methods and techniques are used in determining these requirements.

The world is on the verge of a demographic turning point. The population is expected to continue aging, potentially even at an accelerated pace, due to falling fertility rates and significant increases in life expectancy [2]. With the continuing decline in mortality rates among older adult, the proportion of those aged 80 and over is rising rapidly, and more individuals are living beyond 100. There is growing evidence from international data that, with appropriate policies and programs, people can remain healthy and independent into old age and continue to contribute to their families and communities.

With the introduction of the American Social Security System (Medicare and Medicaid) in the late 1960s, the need for assessment and social work intervention became increasingly critical. At that time, many older adults were hospitalized, and patients who received social work assistance had an average hospital stay of thirty-nine days, compared to eighteen days for those not referred [3]. As the number of vulnerable inpatients grew, social workers needed to identify, as early as possible, those who required their services. Researchers aimed to isolate factors that would enable the early diagnosis and evaluation of older inpatients who could benefit from social work interventions. These early studies found that psychosocial factors are as important as medical indicators in identifying patients likely to experience extended hospital stays and in need of social work support. Furthermore, it was reported that identifying such patients earlier can shorten their hospital stay [4].

In 1998, the John A. Hartford Foundation launched a major long-term initiative to strengthen geriatric social work education. The focus of this initiative is to better prepare social workers to meet the needs of an expanding older adult population. One of the Foundation’s funded programs is the Strengthening Ageing and Gerontology Education in Social Work (SAGE-SW) Project, which is administered by the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). The general aim of SAGE-SW is to enhance gerontological education for all social workers, enabling them to address the needs of a growing older adult demographic [5]. The United States currently has the most developed geriatric social work system, while Ireland is recognized as the only officially “age-friendly” country in the world. Meanwhile, in Türkiye, geriatric services are offered by facilities that are either independent or affiliated with internal medicine.

Old age is one of the main areas of social work intervention. The issues that arise during this period fall under the purview of social work. While social work intervention sometimes accompanies medical treatment as a secondary measure, in other situations, the primary need is for social work intervention itself [6].

Research indicates a growing need for trained geriatric social workers due to population aging and changing family structures [7, 8]. Various training programs have been implemented worldwide to address this need. Banoob (1992) proposed an integrated approach for short-term training of healthcare professionals, including social workers, which was adopted internationally [8]. Bures et al. (2003) discussed graduate-level social work training initiatives in the United States, while Soliman (2021) reported on a successful training program in Egypt that improved social workers’ professional performance with older adults [7, 9]. However, Ayalon (2020) highlighted challenges in implementing such programs, emphasizing the importance of needs assessments and addressing real-life constraints [10]. Despite these challenges, training programs have shown potential benefits, including enhanced professional knowledge, skills, and performance among social workers caring for older adults [7, 9]. These findings underscore the importance of continued development and evaluation of geriatric social work training programs.

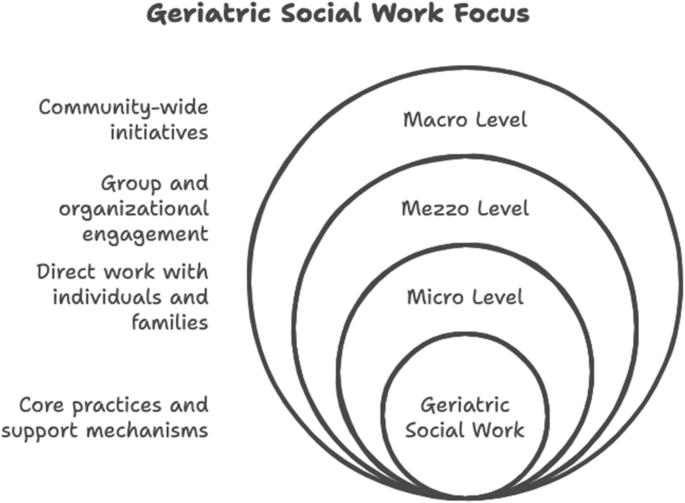

Because a comprehensive geriatric evaluation requires medical, psychological, social, and environmental assessments, it cannot be provided by a single professional group. Sources indicate that this type of evaluation can only be carried out by an interdisciplinary team of professionals, with older adults and their social environment at the center of this team, as shown in Fig. 2 [11].

The study employs the Geriatric Social Work Competency Scale, the UCLA Geriatric Attitudes Scale, and a sociodemographic questionnaire to assess social workers’ educational needs, competencies, and attitudes toward older adults. These scales were chosen for their proven reliability and validity in evaluating key aspects of geriatric social work.

The Geriatric Social Work Competency Scale, developed by Damron-Rodriguez et al. (2006) and adapted into Turkish by Duyan and Tuncay (2015), measures professional knowledge and skills and demonstrates high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.966) [11, 12]. The UCLA Geriatric Attitudes Scale, created by Reuben et al. (1998) and validated in Turkish by Şahin et al. (2012), assesses healthcare professionals’ perceptions and biases regarding aging [13]. These tools have been widely used in research to identify gaps in geriatric education, assess workforce preparedness, and evaluate the effectiveness of training interventions.

The sociodemographic questionnaire complements these scales by examining how factors such as educational background, work experience, and personal exposure to older adults influence social workers’ competencies and attitudes. Together, these measures provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating training needs and informing curriculum development.

Hypotheses of the Research:

The research is analytical in nature and follows a cross-sectional quantitative design. Data were collected via Google Forms from members of the Turkish Association of Social Workers, who volunteered to participate nationwide. The study was conducted between June 20, 2021, and February 2, 2022.

The research population consisted of approximately 3,000 social workers in Türkiye. A convenience sampling method was used to select participants by reaching out to social workers who were readily accessible and willing to participate during the study timeframe. Although this approach is practical, it may limit representativeness because it relies on the accessibility and availability of participants.

The inclusion criteria required participants to be currently practicing as social workers, to be available and willing to participate within the specified timeframe, to provide informed consent, and to submit sufficiently complete responses for analysis. The exclusion criteria involved identifying and removing 28 outlier responses based on statistical analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 (to ensure data reliability and validity), excluding individuals not actively working as social workers, and removing participants with incomplete or invalid survey responses.

Out of 1,647 participants initially reached, 1,619 participants were included in the final analysis after applying the exclusion criteria. This sample size represents a significant proportion of the research population, providing robust data for analysis while acknowledging the potential limitations of the convenience sampling method.

This study employs Kern’s six-step program development model to design a curriculum for social workers specializing in older adults. This model was selected for its comprehensive approach, which integrates various curriculum development frameworks, including those proposed by Taba, Tyler, Yura, and Torres [1]. Within this study, the first two steps of Kern’s model were used to assess educational needs:

Problem Identification and General Needs Assessment:

Targeted Needs Assessment of Learners:

By implementing these steps, the study lays an evidence-based foundation for curriculum development, ensuring that the educational content aligns with the actual needs of social workers who serve older adults.

In this study, three data collection tools were used. First, a questionnaire was administered to gather socio-demographic information about the volunteer professionals who participated. Next, the Geriatric Social Work Competency Scale was applied to determine these professionals’ geriatric social work competency. Finally, the UCLA Geriatric Attitudes Scale was used to assess their attitudes toward aging.

Sociodemographic status form

A structured questionnaire with 16 items was administered to social workers. These items covered gender, age, marital status, education level, graduating faculty, experience working with older adults, willingness to work with older adults, number of undergraduate courses related to aging, number of in-service trainings on aging, whether they currently live with older adults, reading habits related to aging (e.g., books), media or social media follow-up on aging, opinions on geriatric social work education, and desire to pursue graduate or certification programs in geriatric social work.

Geriatric social work competency scale

Originally developed by Damron-Rodriguez et al. (2006) [11], this scale was adapted into Turkish by Duyan and Tuncay (2015) [12]. It demonstrates strong reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.966). The scale consists of 40 items across four dimensions: (1) Values, Ethical, and Theoretical Perspectives; (2) Evaluation; (3) Intervention; and (4) Services, Programs, and Policies Related to Aging. Personal skill levels are measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = no skill to 4 = specialist-level skill). The possible scores range from 0 to 160.

UCLA geriatric attitudes scale (UCLA-GA)

The UCLA Geriatric Attitudes Scale (UCLA-GA) was developed by Reuben et al. in 1998 and adapted into Turkish by Şahin et al. in 2012 [13]. It consists of 14 items grouped into four sub-dimensions: social values, medical care, compassion, and resource allocation. The 1st, 4th, 7th, 9th, and 14th items are positive, while the remaining nine items measure negative attitudes. Negative statements are scored using reverse coding. The scale uses five-point Likert-type items ranging from “1: strongly disagree” to “5: strongly agree.” The minimum and maximum scores for each sub-dimension are as follows: social values (2–10), medical care (4–20), compassion (4–20), and resource allocation (4–20). The lowest possible total score on the scale is 14, and the highest possible total score is 70. Scores of 1 or 2 on each item are considered indicative of a negative attitude, a score of 3 indicates a neutral attitude, and scores of 4 or 5 indicate a positive attitude. As the total score increases, the overall attitude becomes more positive.

The data analysis involved presenting results through descriptive statistics—percentages, means, and standard deviations—to summarize the data, with relationships and comparisons between variables displayed in tables and figures. Statistical significance was noted at p < 0.05. The analysis employed IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0, using methods such as the Mann–Whitney U Test, Run Test (Swed-Eisenhart), Spearman’s correlation, Chi-Square Test with Fisher’s Exact Correction, and Kruskal–Wallis Test. These methods were chosen based on the type of data, research questions, and the need for robust analysis of nonparametric, ordinal, or small-sample data, ensuring comprehensive and rigorous findings.

A total of 1,619 social workers participated in the study, and their sociodemographic data are presented in Table 1. Among the participants, 53.8% were female, the median age was 32, and the average professional experience was 7 years. The average number of in-service trainings attended was 1 ± 2.3, and 67.6% of participants had not received any in-service training on aging. Additionally, 72.1% of participants did not have an older adult living in their household, while the median number of older adults in the household was 2.

The distribution of participants’ responses to the Geriatric Social Work Competency Scale and its subscales, as well as the UCLA Geriatric Attitudes Scale (UCLA-GA), was nonparametric, as shown in Table 2. Consequently, nonparametric tests were utilized for the analysis.

Analysis using the Run (Swed-Eisenhart) test (Table 2) revealed that the mean score on the Geriatric Social Work Competency Scale was 109.6 ± 32 (out of a possible 160 points), with 45.65% of participants scoring below the mean. Similar trends were observed across the Values, Assessment, Intervention, and Service subscales. The mean score on the UCLA-GA was 54.2 ± 4.8 (out of a possible 70 points), with 53.86% of participants scoring below the mean.

Correlations between participants’ age and their scale scores were examined using Spearman’s correlation (Table 2), revealing a weak negative correlation for both scales (p < 0.001). Because of the low correlation coefficient, subsequent categorization based on the Runs Test was applied.

Table 3 presents the relationship between participants’ gender and their scale scores, indicating no significant association (p > 0.05). The table also shows the relationship between participants’ graduated faculty and scale scores, similarly revealing no significant difference (p > 0.05).

Similarly, Table 3 illustrates the relationship between participants’ professional experience and their scale scores, revealing a positive correlation with both the Geriatric Social Work Competency Scale (including its subscales) and the UCLA-GA scale (p < 0.05). The table also presents the relationship between the independent variables—gender, professional experience, in-service training, and living with older adults—and the scale scores.

The relationship between the faculty from which participants graduated and their scale scores is shown in Table 3, with significant correlations observed for the Geriatric Social Work Competency Scale (including its subscales) and the UCLA-GA scale (p < 0.001).

Table 3 presents the relationship between participants’ in-service training participation and their scale scores, indicating a weak correlation with the UCLA-GA scale (rho = 0.20; p < 0.001). Participants who received in-service training scored higher on the UCLA-GA (p < 0.05).

Lastly, Table 3 presents the relationship between participants’ living arrangements with older adults and their scale scores. A significant relationship was observed between living arrangements and scores on the Geriatric Social Work Competency Scale (and its subscales) (p < 0.001), highlighting the positive impact of contact with older adults on geriatric competence. However, no significant relationship was found with attitudes toward aging.

This study aims to evaluate the current status and needs of social workers in order to inform the development of a health education program for older adults. Specifically, it examines social workers’ geriatric competencies, attitudes toward aging, and the factors influencing these attitudes—including the quality of education received, professional experience, familial and environmental influences, perceptions of aging, and interactions with older adults. The study seeks to identify key relationships and areas for improvement to enhance social workers’ effectiveness in supporting the aging population.

In the literature review, it was found that there are very few studies in the geriatric field for social workers. This is the first study to examine social workers’ attitudes toward aging using the "UCLA Geriatric Attitudes Scale," along with factors such as professional experience (which is believed to be related to their geriatric competencies), the quality of education received, familial and environmental influences, perceptions of aging, and interactions with older adults. In addition, the study is expected to make important contributions to the literature by revealing social workers’ geriatric competencies, their accompanying attitudes, and relevant socio-demographic data, as well as by offering suggestions for a training program to improve their geriatric competencies based on the results.

Increasing older adults population

According to data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK, 2023), the proportion of older adults in Türkiye has increased from 8.8% to 10.2% over the past five years. This demographic shift underscores the growing need for social workers with specialized geriatric competencies to address the health, social, and economic challenges faced by the aging population.

Global aging trends

A World Health Organization (WHO) report on global aging [2] highlights that falling fertility rates and increased life expectancy are contributing to rapid population aging worldwide. This global trend is reflected in Türkiye, where the aging population is placing greater demands on social services and healthcare systems.

Limited geriatric education

The study notes that courses related to social work with older adults are often offered as electives in Turkish universities, and there is no mandatory training program for social workers to address the social, psychological, and environmental needs of older adults. This lack of formal education likely contributes to the low geriatric competencies observed among social workers [11, 12].

Variability in University curricula

The study found that the faculty from which social workers graduated influenced their geriatric competencies and attitudes. This suggests that differences in curriculum design—particularly in elective courses—may lead to uneven preparation among graduates [5].

Lack of in-service training

The study revealed that 67.6% of participants had not received any in-service training on aging. This lack of ongoing professional development likely contributes to low levels of geriatric competency and negative attitudes toward older adults [22].

Positive impact of experience

The study found a positive correlation between professional experience and geriatric competencies. Social workers with more experience may have had greater opportunities to interact with older adults, thereby enhancing their skills and attitudes [23].

Stigma and negative perceptions

Cultural attitudes toward aging in Türkiye may influence social workers’ perceptions and attitudes. Negative stereotypes about older adults—for example, viewing them as dependent or burdensome—could contribute to the negative attitudes observed in the study [17].

Intergenerational living

While 72.1% of participants did not live with older adults, those who did demonstrated higher geriatric competencies. This suggests that personal interactions with older adults, such as living with them, can positively influence social workers’ attitudes and skills [23].

Fragmented geriatric services

The study notes that Türkiye has few social workers specifically trained to work in geriatric units. Although social workers in hospitals often provide services to older adults following consultation, without specialized training, they may not be fully equipped to address the complex needs of this population [6].

Interdisciplinary collaboration

An ideal approach to geriatric care involves interdisciplinary teams that include professionals from medicine, psychology, and social work. However, the lack of integration among these fields in Türkiye may hinder social workers’ ability to provide comprehensive care to older adults [4].

Resource limitations

Social workers in Türkiye may face resource constraints, such as limited access to training programs, funding, and support services for older adults. These limitations could impact their ability to develop and maintain geriatric competencies [19].

Workload and burnout

Social workers in Türkiye may also face high workloads and burnout, particularly in under-resourced settings. This may negatively impact their attitudes toward working with older adults and reduce their ability to engage in ongoing professional development [18].

Global aging initiatives

The study aligns with global initiatives, such as the World Health Organization’s Decade of Healthy Aging and the Sustainable Development Goals, which emphasize the need for improved care for older adults [2]. However, implementing these initiatives at the national level in Türkiye may be limited by resource constraints and competing priorities.

Policy gaps

The absence of a national policy or framework for geriatric social work training in Türkiye may contribute to the observed gaps in competencies and attitudes. Without a clear mandate or sufficient support from policymakers, implementing widespread training programs for social workers may be challenging [20, 21].

The study found no significant relationship between gender and geriatric competencies or attitudes among social workers. However, gender dynamics in Türkiye—where women often assume caregiving roles within families—may influence social workers’ experiences and perceptions of aging [14,15,16]. Although social workers do not provide direct caregiving, their understanding of the challenges faced by older adults and their families, particularly in contexts where women are the primary caregivers, can shape their approach to supporting this population. Further research could explore how gender roles and societal expectations impact social workers’ attitudes and competencies in addressing the psychosocial needs of older adults.

This study emphasizes the critical need for a comprehensive training program to address gaps in social workers’ geriatric competencies and attitudes toward aging. The findings indicate that factors such as age, field experience, educational background, in-service training on aging, and personal experiences with older adults are significantly associated with social workers’ self-reported ability to engage with the aging population. To address these gaps, tailored training initiatives should prioritize strengthening geriatric knowledge, fostering positive attitudes toward aging, and providing context-specific practical skills (e.g., crisis intervention, care coordination). Such programs have the potential to enhance social workers’ professional competencies and indirectly improve the quality of care provided to older adults, aligning with the demands of an aging society.

The primary limitation of this study lies in its reliance on quantitative data and predefined scales, which restricted the depth of insights into contextual challenges (e.g., cultural barriers, systemic resource gaps) and the underlying reasons behind observed correlations (e.g., why age or field experience correlates with engagement abilities). The absence of qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, further limited the exploration of social workers’ nuanced experiences and preferences. Future studies should adopt mixed-method approaches to validate these findings through longitudinal or experimental designs, investigate organizational and policy-level factors shaping training needs, and pilot targeted interventions to identify the most effective components of geriatric training programs. Integrating both quantitative and qualitative data would provide a more holistic understanding of how to design contextually relevant and sustainable educational initiatives.

While this study highlights the importance of geriatric training for social workers, its recommendations remain preliminary. Further evidence is needed to establish causal links between training components and care outcomes. Policymakers and educators should use these findings as a starting point for designing iterative, evidence-based programs that integrate both theoretical knowledge and real-world applicability.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

We would like to thank the Turkish Association of Social Workers for their support during the data collection process, as well as Catherine Lane, the native-speaking social worker who reviewed this manuscript.

No funding was received for this study.

The protocol for this research was approved by a suitably constituted Medical Research Ethics Committee of Ege University Faculty of Medicine (Approval No. 21–5.1T/63), and it conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. As this was a questionnaire-based study with anonymous data collection and no intervention, the Medical Research Ethics Committee approved the use of verbal informed consent. Consent was obtained before distributing the questionnaire, with the following statement: “This questionnaire is anonymous, and your answers will be used only for research purposes in this study.”

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Bolukbasi, S., Yilmaz, N.D., Aykar, F.S. et al. Assessment of social workers’ educational needs in geriatric competencies and attitudes towards older adults. BMC Med Educ 25, 432 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-06970-w