BMC Medical Ethics volume 26, Article number: 80 (2025) Cite this article

Moral disengagement can lead to anti-social behaviour by employees in business. In the healthcare field, moral disengagement can lead nurses to make unethical decisions and behaviours that can harm patient well-being. Therefore, this paper will examine the factors influencing moral disengagement among ICU nurses with the aim of contributing to the reduction of the level of moral disengagement among nurses.

Between January 2024 and January 2025, ICU nurses from second-level and above general hospitals in Henan and Hubei, China, were selected as survey respondents. The questionnaire survey was conducted using a general information questionnaire, a moral disengagement scale, a moral resilience scale, and a moral disengagement energy scale, and multiple linear stepwise regression was used to analyze the influencing factors of ICU nurses' moral disengagement.

305 ICU nurses scored (91.40 ± 34.37) on the Moral Disengagement Scale. The multiple linear stepwise regression analysis results showed that years of working experience, whether or not they had received ethics training(16.219 p < 0.001), ears of experience (-7.673, p = 0.018), moral resilience(-18.452,p < 0.001), and moral distress (5.523,p < 0.001) were the influencing factors of moral disengagement among ICU nurses (p < 0.05). The adjusted R2 = 0.499,which explains 49.9% of the total variation, suggests that the model explains the influences of moral disengagement well.

The moral disengagement of ICU nurses is moderately high, and individualized interventions can be carried out for high-risk groups to reduce this level and improve ethical decision-making to protect patient's rights and interests.

Moral decision-making in health care has always been a central topic in nursing ethics. Nursing practice in the intensive care unit (ICU), a critical site for the care of acutely ill patients, is often accompanied by complex ethical conflicts and moral dilemmas [1, 2]. Minute-by-minute life-support decisions compress the time for ethical reflection (e.g., ECMO resource allocation), forcing nurses to rely on intuitive judgment and accelerating responsibility-shifting mechanisms ('just follow the doctor's orders'); vital-signs-monitoring equipment in the ICU reduces the patient to a stream of data (heart rate/oxygen saturation), providing a material basis for dehumanizing desensitization ('monitor alarms'instead of'patient distress'); witnessing an average of 17 times more patient deaths per year than nurses in general wards [22, 23], and emotional depletion directly undermines the capacity for moral self-monitoring.

This makes the ICU a key window into the dynamic formation process of moral excuses—psychological mechanisms that develop slowly in the routine ward are rapidly visualized here by the high-pressure environment. In recent years, the theory of moral disengagement (MDA) has emerged as an important perspective to explain the psychological mechanisms by which healthcare professionals cope with ethical challenges in high-pressure environments [3]. As a core concept of social cognitive theory, moral disengagement, proposed by Bandura, refers to the psychological mechanisms through which individuals decouple their behavior from moral standards through cognitive restructuring, responsibility shifting, and outcome downplaying, thereby alleviating the guilt that arises from violating ethical norms [4]. Bandura's social cognitive theory stresses the interaction between the individual, behaviour and the environment, forming a 'triadic interaction', and points out that an individual's behaviour is not only influenced by the external environment but also regulated by internal cognitive processes. The theory suggests that an individual's cognitive processes play a crucial role in social behaviour. Nursing behaviour is a cognitive process done in social interaction. Nurses' ethical decision-making is shaped by a combination of individual professional perceptions (e.g., ethical values), work environment (e.g., unit culture), and behavioural feedback (e.g., patient responses).

The four principles of nursing ethics (autonomy, doing good, doing no harm, and justice) are often in conflict with each other in reality. The concept of moral disengagement is the key to understanding clinical ethical dilemmas—why might a usually kind nurse be indifferent to a patient? Why do collective irregularities occur? These can be explained by mechanisms such as moral reconfiguration and diffusion of responsibility. For example, when forcing medication on a patient with dementia, 'autonomy' and 'doing good' are at odds. The nurse may be able to alleviate the moral suffering by 'moral rationalisation' by telling herself: 'I am doing it for his good'. This mechanism of psychological protection is precise when analysed using moral disengagement theory.

Moral disengagement is more likely to express resentment and revenge, contributing to aggressive and antisocial behavior [5]. Some research suggests that employees are more likely to adopt moral disengagement coping styles than positive thinking when faced with negative emotions [6]. In healthcare, moral disengagement has an erosive effect on nurses' professional identity and psychological well-being. Nurses who use moral disengagement mechanisms over a long period gradually shift their professional values from 'patient-centered' to 'task-accomplishment oriented,' which exacerbates nurses 'negative emotions and undermines patients' rights [7]. Maftei and others have also found that nurses with higher levels of moral disengagement have lower levels of empathy and are more likely to make unethical decisions [8, 9]. Failure of care associated with morally disengaged staff was found to be common in a qualitative study.

Moral disengagement has been studied more intensively and extensively in other populations and fields; in school students and corporate employees, scholars have found moral disengagement to be a significant contributor to bullying, abuse, and delinquency [10,11,12]. In studies on athletes, scholars have found a mediating role for moral disengagement in empowerment and antisocial behavior [13]. However, research on moral disengagement in healthcare is still in its infancy and lacks analyses of the relationship between psychological resources, ethical dilemmas, and moral disengagement in different psychological resources, ethical dilemmas, and moral disengagement. Moral disengagement, as one of the significant ethical issues, has been studied by scholars from a wide range of professions in terms of its causes, consequences, and interventions. However, the healthcare industry is currently unclear about the precise causes, consequences, and interventions for moral disengagement. The healthcare industry faces more complex ethical issues than most industries, and the well-being of many patients is at stake. Based on some scholars' research on moral disengagement in other fields, there is good reason to suspect that moral disengagement is detrimental to patient well-being. Therefore, research on moral disengagement in the healthcare industry is necessary. This study aims to explore the reasons why moral disengagement arises in the nursing profession with a view to contributing to the proposal of interventions for moral disengagement. Furthermore, nurses 'moral disengagement is not simply a matter of individual moral deficiencies. However, it is a product of the interaction between the structure of the healthcare system, environmental pressures, and individual psychological defense mechanisms. Therefore, this study investigated the moral disengagement of ICU nurses and analyzed its influencing factors to provide a reference for nursing managers to take effective interventions to reduce nurses' moral disengagement, improve nurses 'well-being, and safeguard patients' safety and rights.

The study utilized a cross-sectional design, and data was collected through questionnaires.The sampling method was: convenience sampling.

Between January 2024 and January 2025, ICU nurses from grade II or higher general hospitals in Henan and Hubei, China, were selected. Inclusion criteria:(1) registered nurses. (2) Adult ICU nurses working full-time. (3) ICU nurses working in adult intensive care unit for at least one year. Exclusion criteria:(1) Nurses who are not licensed to practice nursing; (2) ICU nurses who have worked in an adult ICU for less than one year. (3) ICU nurses who did not agree to participate in this study. (4) Nurses working in non-adult ICUs. According to the Kendall sample estimation method [14], the sample size was 5–10 times the number of independent variables, and there were 32 independent variables in this study, which required 200–400 people to be surveyed, considering the 20% inefficiency. This study included 334 people.

The scale was developed into an electronic questionnaire on the Questionnaire Star platform. A part of the questionnaire was collected with the consent of the nursing departments of several hospitals in Henan and Hubei provinces, and the head nurses of selected departments were facilitated to conduct unified training. The head nurses fully informed the nurses who met the inclusion criteria of the study purpose, significance, and method of filling in the questionnaire by using a unified instruction language and then distributing electronic links or QR codes. The other part of the study was open recruitment via the Internet. After verifying that the identity of the recruits met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the researcher informed the participants of the purpose, significance, and method of completing the questionnaire and then distributed the electronic link or QR code. The description section of the questionnaire clearly stated that the survey was mainly for academic research and was completed anonymously and with strict confidentiality to reflect the actual situation of nurses at work as realistically as possible. All items are mandatory; each IP can only complete the questionnaire once. A total of 334 questionnaires were collected; 29 with regular answers were excluded, and 305 were valid, with an effective recovery rate of 91.34%. Specific criteria for questionnaire exclusion: Questionnaire completion time is less than 240 s; Questionnaire answers have regularity. Because some of the questionnaires were recruited via the Internet, it was not possible to count the probability of non-response. Of the nurses recruited for the study, none dropped out midway through the study. The sample was collected without stratified sampling of the sample, but the final results collected included a population with a variety of characteristics.

General information questionnaire

The authors compiled their information, including age, gender, marriage, education level, years of working experience, job title, and number of night shift work per month.

The Chinese version of the moral resilience scale

Was developed by Heinze et al. [15] and Chineseised by Tian et al. [16]. The scale consists of three dimensions, i.e., the ability to cope with moral adversity flexibly (5 items), relational moral soundness (6 items), and moral efficacy (6 items), with a total of 17 entries. The scale is based on a 4-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 to 4, from 'disagree' to 'agree,' and a total score of 17 to 68, with higher scores representing greater moral resilience. The Cronbach for this scale is 0.811.

The Chinese version of the Moral Dilemma Scale for Nurses (MDS-R)

Developed by Corley et al. and Chineseised by Professor Sun Xia [17, 18]. The scale consists of three dimensions, namely, individual responsibility (8 items), failure to safeguard the best interests of patients (5 items), and value conflict (6 items), with a total of 22 items, each of which consists of two items, namely, frequency and degree, which are assigned 0 to 0 on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 'never occurring' to 'very frequent' and 'seriously disturbed.' Each entry was scored as the product of the frequency and intensity scores, and the scale score was the total score of each entry. The total score ranged from 0 to 352; the higher the score, the stronger the moral distress. The expert content validity index is 0.909, and the Cronbach coefficient is 0.896.

Citizen's moral disengagement scale

The Citizen's Moral Disengagement scale was developed by Caprara et al. and translated and revised by Xingchao Wang et al. [19, 20]. The scale has eight dimensions: moral defenses, euphemistic labels, favorable comparisons, responsibility shifting, responsibility dispersal, distorted outcomes, blame attribution, and dehumanization. Each dimension has four entries each, for a total of 32 entries. The Likert 5 scale was used, with scores ranging from 1 to 5, from 'disagree' to 'agree,' and total scores ranging from 32 to 160, with the higher scores being the more substantial the moral disengagement. The alpha coefficient was 0.91, and the split-half reliability coefficients were 0.85 and 0.82, respectively. The alpha coefficient was 0.91, and the split-half reliability coefficients were 0.85 and 0.82, respectively.

Before distributing the study survey and collection of data, participants were informed via voice message that the study was voluntary, confidential, and anonymous. When they clicked on the online survey link, they were again informed in writing of the study's purpose and the participants'rights. The researcher was the only person entitled to access the data. The study emphasized the importance of maintaining confidentiality, data security, informed consent, and voluntary participation.

SPSS 20.0 statistical software was used to analyze the data. Count data were expressed as frequencies and percentages; measured data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation; comparisons between groups were made by two independent samples t-test or ANOVA; comparisons of moral disengagement, moral resilience, and moral distress among ICU nurses were made by Pearson's correlation analysis; and multivariate linear stepwise regression analyses made multifactorial analyses. The test level was α = 0.05.

This study included 305 ICU nurses. Independent sample t-tests for gender, willingness to resign, and whether or not they had received ethics training were conducted to test the relationship between participants'general characteristics and moral disengagement. The remaining general information was analyzed using one-way ANOVA. See Table 1 for details.

305 ICU nurses had a total moral disengagement score of (91.40 ± 34.37) and an entry score of (2.85 ± 1.07); a total Moral Justification score of (11.37 ± 4.67) and an entry mean of (2.84 ± 1.16); a total euphemistic labeling score of (11.41 ± 4.69) and an entry mean of (2.85 ± 1.17); a total advantageous comparison score of the score is (11.24 ± 4.68), and the mean of entries is (2.81 ± 1.17); total responsibility shifting score is (11.27 ± 4.82) and the mean of entries is (2.81 ± 1.21); total responsibility dispersal score is (11.63 ± 4.45) and the mean of entries is (2.90 ± 1.11); and total distortion of results score is (11.14 ± 4.78) and the mean of entries (2.78 ± 1.20); blame attribution total score (11.97 ± 4.26), mean of entries (2.99 ± 1.07); dehumanization total score (11.34 ± 4.58), mean of entries (2.83 ± 1.15).

The results of this study showed that years of working experience, hospital level, marital status, education, whether or not they had received ethics training, and monthly income were the factors influencing moral disengagement, and the differences were statistically significant (all P < 0.05). See Table 1.

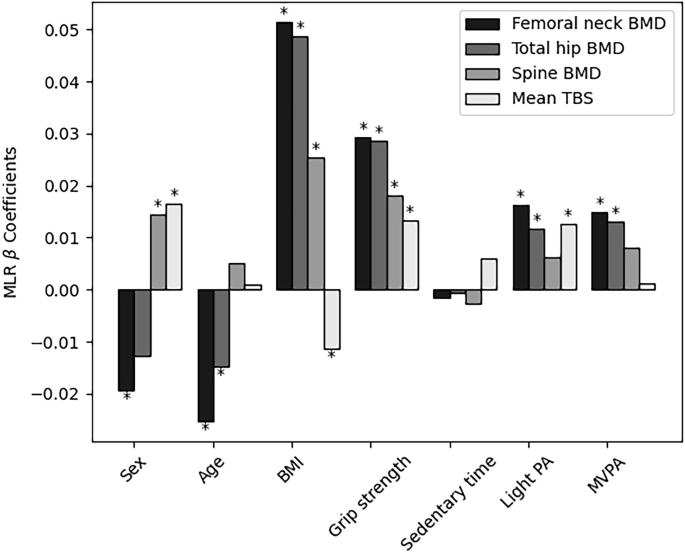

The scores of moral resilience dimensions from high to low were moral efficacy (17.28 ± 4.39), relational moral soundness (14.31 ± 4.40), and the ability to respond flexibly to moral adversity (11.80 ± 3.99). Pearson correlation analysis showed that ICU nurses'moral disengagement scores were negatively correlated with moral resilience scores of ability to respond flexibly to moral adversity and relational moral soundness scores (both P < 0.05) and not with moral efficacy scores (both P > 0.05). The scores for each dimension of moral distress, from highest to lowest, were individual responsibility (41.21 ± 28.38), value conflict (35.45 ± 20.61), failure to uphold patients'best interests (27.61 ± 17.4), and harm to patients'interests (15.16 ± 10.92). Best interests, value conflict, and harming patient interests scores were positively correlated (all P < 0.05). See Table 2.

The total number of ICU nurses' moral disengagement was used as the dependent variable, the variables with statistically significant 7 characteristics in the univariate analysis and the variables with statistically significant correlation analysis were used as the independent variables, the categorical variables were assigned as shown in Table 3, and the continuous variables were brought in at their original values. Multiple linear stepwise regression was used to analyze the factors influencing moral disengagement among ICU nurses. The results showed that whether or not they had received ethical training, years of experience, moral resilience, and moral distress were influential factors for ICU nurses' moral disengagement (P < 0.05), explaining 49.9% of the total variance, as shown in Table 4.

The results of this study showed that the total moral disengagement score of ICU nurses was (91.40 ± 34.37) scoring 57.12%, which is moderately high and higher than the results of the study conducted by Zhong Xiaoyanet al. on the level of moral disengagement of nurses in the operating theatre [21]. This may be due to 1. the difference between ICU and operating theatre environments and the content of nurses'work.ICU nurses are faced with critically ill patients and have to work with multidisciplinary cooperation to complete the work. Operating theatre nurses may be more interested in working as facilitators during surgery. 2. The data collection period of the study by Zhong Xiaoyan et al. was from 2016–2018, which is 7–8 years earlier than this study. During this 7–8 year period, Chinese hospitals experienced major events such as healthcare reform and new coronary pneumonia. These events may have made the nurse community aware of their weakness and powerlessness in the face of disease. Prolonged exposure to systemic deficiencies that cannot be changed may lead to learned helplessness. Feeling ineffective in their efforts, nurses lower their ethical standards and are more likely to use moral disengagement to rationalise such unethical behaviour (e.g., it is the system's fault that nothing is good enough anyway).

It has been suggested that cumulative adverse life events are associated with smaller volumes of grey matter in key areas of the brain involved in emotional, social and self-regulation, but the two are not causally related.

We might hypothesise that frequent exposure to treatment failure might lead to a reduction in the grey matter volume of the ICU nurse's brain and a diminution of emotional resonance, which could lead to the activation of moral disengagement mechanisms, such as explaining the death of a patient as a'natural consequence of the course of the disease'rather than a medical limitation.

In the decision-making pyramid of the ICU, nurses are often at the end of the information chain. A German qualitative study revealed that most senior nurses chose to remain silent when a young doctor intubated against the patient's will, thinking: 'I am just the one who carries it out,' which triggers the dispersion of responsibility in moral disengagement [24]. Among the eight dimensions of ethical disengagement, blame attribution (2.99 ± 1.07) entries had the highest mean score. It indicates that ICU nurses use it more often to justify their unethical behaviour in their clinical work. Blame attribution belongs to the self-interested attributional approach, which refers to overemphasising the fault of the victim and attributing the consequences of the unethical behaviour to the victim, with no fault or responsibility on one's part [4]. This may be related to the fact that nurses in the ICU rely more on a teamwork model of working. When nurses realise that their actions (or omissions) may have led to undesirable consequences, great fear and guilt trigger strong psychological defences.ICU nurses are more likely to find external factors ('unclear doctor's orders','family interference','equipment sucks') or others ('the relief nurse did not explain it clearly',"the carer did not cooperate") to deflect the pain of self-blame.

The study found higher levels of moral disengagement among ICU nurses who did not receive ethics training (P < 0.001). This may be because ethics training helps nurses build ethical analysis skills by systematically teaching ethical principles (e.g., patient autonomy, the principle of doing good) and decision-making models (e.g., the four-quadrant method), which enhances nurses' ability to recognize ethical conflicts. Untrained nurses are more likely to rely on intuitive or empirical judgments and are prone to 'black and white' simplistic thinking [25]. Furthermore, untrained nurses may have inadequate ethical knowledge and coping skills, leading to homogenization of coping strategies, which may trigger moral disengagement in the event of failure to cope with ethical issues. Lastly, untrained nurses with inadequate ethical sensitivity lead to nurses being more likely to ignore the moral consequences of their actions, which in turn activates the moral disengagement mechanism [26].

This study found higher levels of moral disengagement among ICU nurses who had worked for 6–10 years (p < 0.001). This may be because Nurses at this stage of their career may be in mid-career, face pressure for promotion or role change, and may have to put more energy into their lives to care for their families. If there is a lack of support, they are prone to higher burnout, and some studies have shown that ICU nurses who have worked for 6–10 years have a higher incidence of severe burnout [27], and higher burnout may lead them to use moral disengagement more frequently to cope with stress. As they gain clinical experience, 6–10-year-old nurses are more aware of the limitations of the healthcare system (e.g., inequitable resource allocation, defensive medicine). However, they cannot change the system and are prone to a sense of 'systemic powerlessness, 'which may lead to a greater tendency to shirk responsibility [28]. ICU nurses with 6–10 years of experience have a richer work history, but at the same time, this group has witnessed colleagues or experienced more occupational risk events themselves. Senior nurses may over-rely on standardized processes (e.g., mechanical enforcement of restraints) to avoid occupational risk events [29], but such strategies also promote nurses' dehumanization of patients, leading to a decrease in the flexibility of ethical judgment and thus the development of higher levels of moral disengagement [30, 31]. Most ICU nurses of 6–10 years have become the backbone of the unit and are responsible for caring for the sickest patients in the unit all year round. Prolonged heavy exposure to patient suffering and death leads to depletion of emotional resources, and nurses may have contributed to moral disengagement through emotional isolation (e.g., reduced in-depth communication with patient's family members) and rationalization of techniques (e.g., 'Oxygenation index is more important than the patient's facial expression') This also contributes to moral disengagement. This suggests that managers should pay more attention to the group of nurses who have been working for 6–10 years and give them more support. Nursing managers can provide supportive resources to nurses at this stage of their careers through ethics training, the establishment of interdisciplinary ethics counseling teams, and the creation of a climate for non-judgmental ethical discussion while increasing their self-efficacy [28, 32].

This study found that ICU nurses with lower levels of moral resilience had higher levels of moral disengagement. Rushton (2016) defined moral resilience as'the ability to maintain or regain his or her integrity in response to moral complexity, confusion, or frustration [26]. According to the conservation of resources theory, moral resilience requires a sustained investment of emotional, cognitive, and social support resources [33]. ICU nurses are chronically exposed to high-pressure scenarios of life-and-death decision-making and ineffective treatment, which can lead to the rapid depletion of psychological resources. When moral resilience is insufficient, nurses lack the resources to respond positively to ethical conflicts and turn to moral disengagement (e.g., 'blame shifting and outcome distortion') to reduce psychological burden. This study also found that moral disengagement was negatively related to the ability to cope flexibly with ethical adversity and relational moral soundness(p < 0.001) but not to moral efficacy (p > 0.05). Flexibility to cope with ethical adversity refers to the ability to adjust strategies to balance ethical principles and practical constraints in complex situations (e.g., ICU nurses optimizing patient dignity care under resource constraints), relational moral soundness refers to adherence to ethical values in interpersonal interactions and maintenance of trusting relationships with patients and colleagues, and ethical efficacy is the belief in one's ability to deal with ethical issues and influence [16]. Both are about being true to one's values and beliefs to do what is morally right, a key feature of integrity [34]. The latter is an awareness of the state of the self. When a person is fully convinced that they know the right thing to do, he or she carries out his or her decisions without considering the opinions and desires of others. This reflects a moral arrogance that can potentially harm the patient [34]. This phenomenon is confirmed in the athlete population: moral disengagement was found by Gürpınar et al. to mediate empowering and antisocial behaviors in athletes [12]. This suggests the importance of managers'moral values molding ICU nurses and enhancing skills to cope with moral conflicts. It also suggests that future research should focus more on the relationship between moral disengagement and moral efficacy.

This study found that ICU nurses with higher levels of moral distress had higher levels of moral disengagement (p < 0.001). Moral distress is used to interpret a psychological constraint and conflict that arises when nurses cannot act according to their moral values and beliefs due to external environmental factors. This psychological burden creates negative emotions for nurses, such as stress, depression, frustration, and anxiety [35, 36]. At the heart of moral distress lies the 'knowledge-action conflict'—an ethical behavior that nurses know they should adopt but cannot do so due to institutional constraints (e.g., lack of resources, family pressure, or conflicting medical advice). In the ethical distress of the patient-nurse ratio imbalance, nurses are forced to simplify pain assessment, triggering strong cognitive-emotional dissonance [1]—knowing that this violates the principle of do no harm [2], but unable to perform a complete assessment. To alleviate moral distress, some nurses activate moral disengagement mechanisms [3]: reframing the behaviour as 'efficiency optimisation' through euphemistic labelling and attributing management system deficiencies through blame shifting. When the ethical climate of the unit acquiesces to such compromises, diffusion of responsibility ('everyone else does it') further erodes ethical sensitivity [4], creating a vicious circle—the moral resilience buffer model fails [5]. Alternative explanations not considered: Because the study was cross-sectional, no causal explanation could be drawn. Therefore, we can also consider the possibility that the level of moral distress is exacerbated when nurses repeatedly adopt moral disengagement mechanisms. When nurses adopt moral disengagement mechanisms, the subconscious mind may remain aware of the inconsistency between internal cognition and external behaviour. This leads to moral distress.

This is a cross-sectional study, and none of the ethical training, years of work experience, moral toughness, or moral distress mentioned in the text can be inferred to have a causal relationship with moral disengagement. Secondly, the study sample included only 305 ICU nurses, so the sample size was small. It would be beneficial to expand the sample size and conduct the study in different regions and levels of hospitals to obtain more reliable data. In addition, the use of a self-reported questionnaire format may introduce a degree of subjectivity in the results, which may limit the generalisability of the findings. Therefore, it is recommended that follow-up studies may include different levels of healthcare and cross-regional groups of nurses through stratified sampling and use a multi-center, longitudinal follow-up design to enhance the reliability and generalisability of the findings.

In conclusion, the results of this survey indicate that ICU nurses have relatively high levels of moral disengagement. Specifically, years of work experience, whether or not they have received ethical training, moral resilience, and moral distress were identified as independent factors that significantly influence ICU nurses'moral disengagement. In order to reduce the level of moral disengagement among ICU nurses, nursing administrators should pay attention to this psychological problem among ICU nurses, accurately identify at-risk populations, and provide them with supportive resources in order to reduce their level of moral disengagement and to better provide safe, high-quality nursing care to patients.

We guarantee that this manuscript is original, has not been published, and will not be submitted for publication elsewhere when it is under consideration by BMC Medical Ethics. Furthermore, the study has not been divided into sections over time to increase the number of journal submissions.

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Our sincere thanks go to all participants of the study.

Not applicable.

The current study did not obtain any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, Commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Each method complied with the relevant rules and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki (DoHOct2008). Ethical approval for data collection was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Wuhan University Renmin Hospital (No. WDRY2021-K155). Nurse educators who agreed to participate in this study had obtained informed written consent.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

He, J., Zhang, Y., Zhang, F. et al. Analysis of the current situation of ICU nurses' moral disengagement and influencing factors. BMC Med Ethics 26, 80 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-025-01245-x