African prisoners made sound recordings in German camps in WW1: this is what they had to say

During the first world war (1914-1918) thousands of African men enlisted to fight for France and Britain were captured and held as prisoners in Germany. Their stories and songs were recorded and archived by German linguists, who often didn’t understand a thing they were saying.

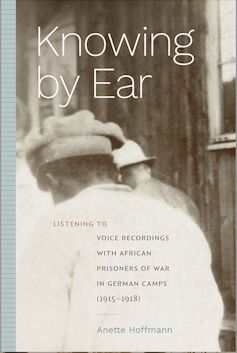

Now a recent book called Knowing by Ear listens to these recordings alongside written sources, photographs and artworks to reveal the lives and political views of these colonised Africans from present-day Senegal, Somalia, Togo and Congo.

Anette Hoffmann is a historian whose research and curatorial work engages with historical sound archives. We asked her about her book.

About 450 recordings with African speakers were made with linguists of the so-called Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission. Their project was opportunistic. They made use of the presence of prisoners of war to further their research.

In many cases these researchers didn’t understand what was being said. The recordings were archived as language samples, yet most were never used, translated, or even listened to for decades.

The many wonderful translators I have worked with over the years are often the first listeners who actually understood what was being said by these men a century before.

The European prisoners the linguists recorded were often asked to tell the same Bible story (the parable of the prodigal son). But because of language barriers, African prisoners were often simply asked to speak, tell a story or sing a song.

We can hear some men repeating monotonous word lists or counting, but mostly they spoke of the war, of imprisonment and of the families they hadn’t seen for years.

Abdoulaye Niang from Senegal sings in Wolof. Courtesy Lautarchiv, Berlin275 KB (download)

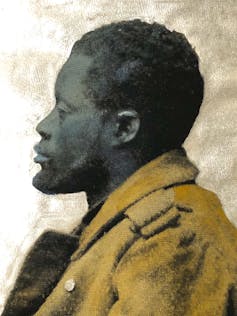

In the process we hear speakers offer commentary. Senegalese prisoner Abdoulaye Niang, for example, calls Europe’s battlefields an abattoir for the soldiers from Africa. Others sang of the war of the whites, or speak of other forms of colonial exploitation.

When I began working on colonial-era sound archives about 20 years ago, I was stunned by what I heard from African speakers, especially the critique and the alternative versions of colonial history. Often aired during times of duress, such accounts seldom surface in written sources.

Joseph Ntwanumbi from South Africa speaks in isiXhosa. Courtesy Lautarchiv, Berlin673 KB (download)

Clearly, many speakers felt safe to say things because they knew that researchers couldn’t understand them. The words and songs have travelled decades through time yet still sound fresh and provocative.

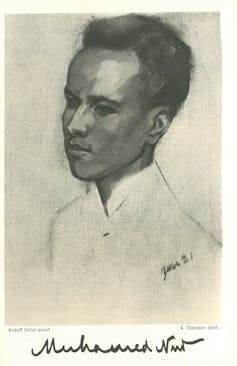

The book is arranged around the speakers. Many of them fought in the French army in Europe after being conscripted or recruited in former French colonies, like Abdoulaye Niang. Other African men got caught up in the war and were interned as civilian prisoners, like Mohamed Nur from Somalia, who had lived in Germany from 1911. Joseph Ntwanumbi from South Africa was a stoker on a ship that had docked in Hamburg soon after the war started.

In chapter one Niang sings a song about the French army’s recruitment campaign in Dakar and also informs the linguists that the inmates of the camp in Wünsdorf, near Berlin, do not wish to be deported to another camp.

An archive search reveals he was later deported and also that Austrian anthropologists measured his body for racial studies.

His recorded voice speaking in Wolof travelled back home in 2024, as a sound installation I created for the Théodore Monod African Art Museum in Dakar.

Chapter two listens to Mohamed Nur from Somalia. In 1910 he went to Germany to work as a teacher to the children of performers in a so-called Völkerschau (an ethnic show; sometimes called a human zoo, where “primitive” cultures were displayed).

After refusing to perform on stage, he found himself stranded in Germany without a passport or money. He worked as a model for a German artist and later as a teacher of Somali at the University of Hamburg. Nur left a rich audio-visual trace in Germany, which speaks of the exploitation of men of colour in German academia as well as by artists. One of his songs comments on the poor treatment of travellers and gives a plea for more hospitality to strangers.

Stephan Bischoff, who grew up in a German mission station in Togo and was working in a shoe shop in Berlin when the war began, appears in the third chapter. His recordings criticise the practices of the Christian colonial evangelising mission. He recalls the destruction of an indigenous shrine in Ghana by German military in 1913.

Also in chapter three is Albert Kudjabo, who fought in the Belgian army before he was imprisoned in Germany. He mainly recorded drum language, a drummed code based on a tonal language from the Democratic Republic of Congo that German linguists were keen to study. He speaks of the massive socio-cultural changes that mining brought to his home region, which may have caused him to migrate.

Together these songs, stories and accounts speak of a practice of extracting knowledge in prisoner of war camps. But they offer insights and commentary far beyond the “example sentences” that the recordings were meant to be.

As sources of colonial history, the majority of the collections in European sound archives are still untapped, despite the growing scholarly and artistic interest in them in the last decade. This interest is led by decolonial approaches to archives and knowledge production.

Sound collections diversify what’s available as historical texts, they increase the variety of languages and genres that speak of the histories of colonisation. They present alternative accounts and interpretations of history to offer a more balanced view of the past.