Advances in organic electronics and optoelectronics

NAE profile: Steve Forrest, Electrical and Computer Engineering

The Highest Honor

Get to know Michigan Engineering’s National Academy of Engineering members.

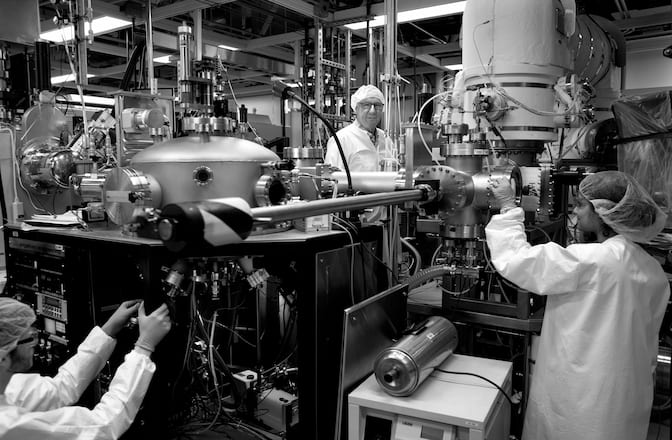

Steve Forrest profoundly impacted various fields through technological innovations and entrepreneurship. At Bell Labs, he played a crucial role in developing fiber optic communications, a cornerstone of modern telecommunications infrastructure. He created the first stable optical detector for long-haul communications— a design still used today. Forrest’s entrepreneurial spirit led to co-founding companies that turned lab innovations into practical applications: co-founding Universal Display Corporation, Forrest advanced OLED technology, now essential in TV and mobile displays. His research in organic solar cells led to innovative applications like power-generating windows and agricultural solutions that don’t compete for land.

For these advances in optoelectronic devices, detectors for fiber optics, and efficient organic LEDs for displays, Forrest was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 2003. View the NAE citation.

On this page

In their own words

“I grew up in Southern California, in Los Angeles. And when I went to college, I went to U.C Berkeley as an undergraduate in physics. I worked a little while in Silicon Valley in the very, very early days, which was quite fun.

“Soon I realized that there was a lot I didn’t know. So I decided to apply to graduate school, and by total random choice, I chose the University of Michigan. I knew nothing about Michigan. I barely knew where it was on the map, but I knew I wanted to get out of California. So I came to spend five plus years here getting my Ph.D. in condensed matter physics, which is a fancy way of saying I looked at what in those days we call ultrafine ion particles.”

“I started studying this thing called light wave communications, which I had never heard of, and I decided to try something new. I was tired of magnetism, and I went into this thing called optical communications, fiber optic communications. That was probably the most important decision I ever made in my life beyond just going to school, because I got in on the ground floor of figuring out how to make components and systems for fiber optic communication—which of course now rules our lives.

“Bell Labs was just an incredible place in those days. While I was there, I was assigned to try to figure out how to make good photo detectors. A couple of people and I demonstrated the first optical detector that was stable for long haul communications. They’re still used today, by the millions. We came up with this organic material and we started studying it quite unexpectedly, to see if it was conducting or could make conducting polymers. It had a whole bunch of unexpected properties. So that was exciting. We made some very interesting early devices that were quite good in organics. That’s when I decided, “I want to go to university and become a professor.”

“I really feel that for young people—it’s the one time in your life you can be truly passionate about something and really focus on just your life. When you get a lot of responsibilities, you have this spreading out of duties. I think when I was young, I was really lucky because I was in the ‘space race’ generation going to the moon. So everything was kind of magical in the technological world. I was completely absorbed by it. I was really excited… and I see less of that excitement today.

“My advice to young people is just get involved and follow your passion and see where it leads you. That may not be your passion tomorrow, but don’t hold off and expect it to come later. If you’re not passionate when you’re young, you’re never going to be passionate, right? Because everything is new. It’s all about discovery, discovering who you are, discovering what life is like, and making friends that you might actually have for quite a duration in your life. Find something at the university or wherever you are that really excites you and follow it.”

“People talk a lot about work life balance today. I’m not so sure I understand what that means because work is part of life. There are various elements of your life to balance and work is just one of them. It’s not like it’s a separate thing.”

“I have three children. They’re fantastic people, adults, but they didn’t have a linear process of growing up and when they were really quite young, I was very busy. I had to make compromises at that period of your life, you know. Do you focus on your laboratory? Do you focus on your kids? You’re never going to get that right, ever.

“Getting people and particularly your own children on a track that’s a good track is not trivial. It takes a huge amount of effort. So I think that was the biggest challenge in my life. When you’re with your family, you’re thinking you need to be at work. And when you’re at work, you think you need to be with your family. That’s where the tradeoff is.”

“I think ultimately AI is going to create a lot of jobs because all technologies do. It will also create a lot of social displacement because the jobs we have today will not be the jobs that are going to be valuable in the future. It’s just like when the Internet replaced brick-and -mortar stores. That put a lot of people out of work, but it also created more jobs than were lost. That was true of the Industrial Revolution, too. I think where AI’s going to make a difference is in the production of information. We have lots and lots of people involved in that information production chain, from administrative assistants to people like me.

“My son, my youngest, is a software engineer and he’s telling me how he’s going to be out of a job very soon because of AI. It’s hard to relax. He says they now can make these PowerPoint presentations much better than when they’re made by you. And I say, yes, but who’s going to consume those PowerPoint presentations in the future?

“The problem that we’re facing today is these types of innovations come along so quickly that the social displacement becomes unrecoverable. It just keeps going on and on and on. The churn is too fast. When we went from an agrarian to a mechanical society in the industrial Revolution, that was the first time, right? And so it was slow and everybody adjusted. 20 years later life was more or less back to normal. Then the railroad came, same problem. It put out the Pony Express and a lot of the old ways of communicating. But it was okay because it created lots of jobs but just different ones. So it takes time for humans to adjust. And I think we’re entering a period where these innovations and these displacements are just coming too rapidly.”

Quotes edited from interview transcript between Steve Forrest and Marcin Szczcepanski.